Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism

John A. Heit

Thrombosis can affect virtually any venous circulation. This chapter focuses on the epidemiology of common deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the leg, arm, or pelvis, and its complication, pulmonary embolism (PE). Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a complex (multifactorial) disease, involving both environmental exposures (e.g., clinical risk factors) as well as genetic and environmental interactions. Most epidemiology studies of VTE addressed populations of primarily European origin, and the data discussed in this chapter mainly relate to these populations. Where available, data from populations originating from other continents are presented. This chapter focuses on population-based studies of VTE incidence, survival, recurrence, and risk factors.

▪ INCIDENCE OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS AND PULMONARY EMBOLISM

The estimated average annual incidence rate of VTE among persons of European ancestry ranges from 104 to 183 per 100,000 person-years.1,2,3,4,5,6 The incidence is similar or higher among African Americans7,8 and lower among Asians,9 and Asian10 and Native Americans.11 Unlike atherosclerotic arterial disease, the low incidence of VTE among Asians does not appear to increase after emigration and adoption of a western civilization diet and lifestyle, underscoring the probable role of heritability in the etiology of VTE. Using the age- and sex-specific incidence rates for the 5-year time period, 1991 to 1995, projected to the 2000 United States white population, at least 260,000 new cases of VTE occur among whites in the United States annually.4 If incidence rates among African Americans are similar, then 27,000 additional incident cases occur among African Americans in the United States annually.

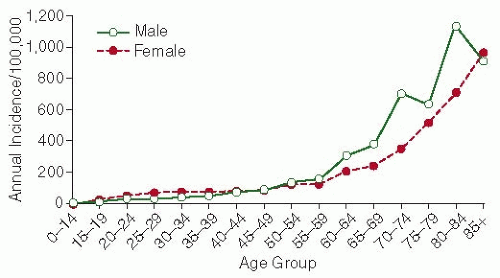

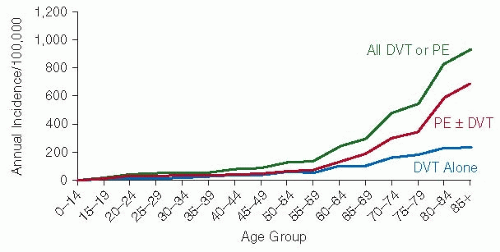

VTE is predominantly a disease of older age.1,2,3,4,5,6,12 In the absence of a central venous catheter13 or thrombophilia,14 VTE is rare prior to late adolescence.1,15 Incidence rates increase markedly with age for both men and women (FIGURE 82.1) and for both DVT and PE (FIGURE 82.2).1,5,6 The overall age-adjusted incidence rate is higher for men (130 per 100,000) than women (110 per 100,000; male:female sex ratio is 1.2:1).1,6 Incidence rates are somewhat higher in women during the childbearing years, while incidence rates after the age of 45 years are generally higher in men. PE accounts for an increasing proportion of VTE with increasing age for both sexes.1

▪ SURVIVAL AFTER DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS AND PULMONARY EMBOLISM

Overall, survival after VTE is worse than expected, and survival after PE is much worse than after DVT alone (Table 82.1).16,17,18,19 The risk of early death among PE patients is 18-fold higher compared with DVT patients alone.16 PE is an independent predictor of reduced survival for up to 3 months after onset. After 3 months, observed survival after PE is similar to expected survival.6,16,17 For almost one-quarter of PE patients, the initial clinical presentation is sudden death. Independent predictors of reduced early survival after VTE include increasing age, male sex, lower body mass index, confinement to a hospital or nursing home at VTE onset, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, serious neurologic disease, and active malignancy.16,17,20 Additional clinical predictors of poor early survival after PE include syncope and arterial hypotension.20,21 Evidence of right heart failure based on clinical examination, plasma markers (e.g., cardiac troponin T, brain natriuretic peptide), or echocardiography predicts poor survival among normotensive PE patients.20 Survival over time may be improving for those PE patients living sufficiently long to be diagnosed and treated.16,22,23 The risk of a diagnosis of subsequent cancer is significantly increased within the first 6 to 12 months after an incident of DVT or PE.24,25

▪ VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM RECURRENCE

VTE recurs frequently; about 30% of patients develop recurrence within the next 10 years.26 The hazard of recurrence varies with the time since the incident event and is highest within the first 6 to 12 months but never falls to zero (FIGURE 82.3). The aim of acute anticoagulation treatment for acute VTE is to prevent DVT extension and embolization. The duration of acute treatment must be individualized but generally ranges from 3 to 6 months. After this period of time, the acute thrombus is either lysed or organized and unlikely to extend or embolize. From this time forward, any continued anticoagulation is to prevent recurrent VTE (i.e., secondary prophylaxis). The duration of acute treatment does not affect the risk of recurrence after anticoagulation is stopped,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 suggesting that VTE is a chronic disease with episodic recurrence.26,34,35,36 Independent predictors of recurrence include increasing patient age and body mass index,26,37 neurologic disease with leg paresis,26 and active cancer.3,26,34,35,38,39 Among cancer patients, the hazard of VTE recurrence is significantly increased with lung, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary (uterus, kidney, ovary, testicle, bladder, prostate) cancer, and with extensive or moderately extensive cancer disease.35 While men have been reported to have a higher risk of recurrence compared to women,40,41,42 sex is not an independent predictor of recurrence after adjusting for sex-specific risk factors.26,43 Additional predictors of VTE recurrence include “idiopathic” VTE,29,30,44,45 a lupus anticoagulant or antiphospholipid antibody,28,46 antithrombin, protein C or protein S deficiency,47,48,49 hyperhomocysteinemia,50 inflammatory bowel disease,51 a persistently increased plasma

D-dimer among patients with idiopathic VTE,52,53,54 and possibly persistent residual DVT.55 Anticoagulant-based secondary prophylaxis should be considered for patients with these characteristics.

D-dimer among patients with idiopathic VTE,52,53,54 and possibly persistent residual DVT.55 Anticoagulant-based secondary prophylaxis should be considered for patients with these characteristics.

Equally important is the fact that several baseline characteristics predict either a reduced risk of recurrence or are not predictive of recurrence.26,30,34,38,45,56 For women, pregnancy or the postpartum state,26,57 oral contraceptive use,26 hormone therapy,58 and gynecologic surgery26 are associated with a reduced risk of recurrence. Recent surgery and trauma/fracture either have no effect26 or predict a reduced risk of recurrence.38 Additional characteristics having no significant effect on recurrence risk include recent immobilization, tamoxifen therapy, and failed prophylaxis.26 For these patients, and for patients with isolated calf vein thrombosis, a shorter duration of acute therapy likely is adequate.30,44,59 While the reported risk of recurrence by incident event type (DVT alone vs. PE) varies with one report suggesting a higher recurrence risk associated with incident PE,19,26,59 patients with recurrence are significantly more likely to experience recurrence of the same event type as the incident event type.60 Because the 7-day case fatality rate is significantly higher for recurrent PE (34%) compared to recurrent DVT alone (4%),61 secondary prophylaxis should be considered for patients with incident PE, especially those with chronic heart and/or lung disease causing reduced cardiopulmonary functional reserve; it is these patients who are most likely to die from recurrent PE.

FIGURE 82.2 Annual incidence of all VTE, DVT alone, and pulmonary embolism with or without DVT (PE ± DVT) by age. (From Silverstein M, Heit J, Mohr D, et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based, cohort study. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:585-593).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|