Carlos del Rio, James W. Curran

Epidemiology and Prevention of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the most severe manifestation of a clinical spectrum of illness caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The syndrome is defined by the development of serious opportunistic infections, neoplasms, or other life-threatening manifestations resulting from progressive HIV-induced immunosuppression. AIDS was first recognized in mid-1981, when unusual clusters of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma were reported in young, previously healthy homosexual men in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.1,2 The subsequent documentation of cases among persons with hemophilia, blood transfusion recipients, and heterosexual injection drug users (IDUs) and their sex partners suggested that a transmissible agent was the primary cause of the immunologic defects characteristic of AIDS. In 1983, 2 years after the first reports of AIDS, a cytopathic retrovirus was isolated from persons with AIDS and associated conditions such as chronic lymphadenopathy.3,4 By 1985, serologic tests to detect evidence of infection with HIV had been developed and licensed.

Blood obtained in 1959 from an adult Bantu man living in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo represents the oldest known case of HIV-1 infection in the world.5 HIV sequences from that sample as well as others from the same region in Africa suggest that humans acquired a common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group by cross-species transmission under natural circumstances in approximately 1933 (1919 to 1945).6 HIV infection has become pandemic, affecting every region of the world, and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, particularly among young adults. HIV is spread primarily through heterosexual contact, with women now accounting for more than half of new HIV infections in adults.7 Transmission through transfusion of blood and blood products has been virtually eliminated in countries that have systematically instituted HIV antibody screening of donated blood and plasma and heat treatment of clotting factors. In developed countries, sharp declines in the incidence and mortality of AIDS have been noted after the use of active antiretroviral therapy (ART) became widespread in 1996.8 As a result, the number of persons living with HIV infection continues to rise, and evidence suggests that new infections in the United States remain stable, except among men who have sex with men (MSM) and, in particular, black young MSM, in whom rates have increased.9 In the United States, the HIV epidemic increasingly affects women, minorities, persons living in the Southeast, and the poor.10,11 The control and prevention of HIV infection, whether on a global or an individual scale, must be grounded in an understanding of the changing epidemiology of HIV.

HIV and AIDS Surveillance in the United States

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collects, analyzes, and disseminates surveillance data on HIV infection and AIDS. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all U.S. territories require the reporting of AIDS cases to local health authorities by name, and they in turn use a uniform surveillance case definition and case report form to report cases to the CDC.12 Confidential name-based HIV infection is now also reported from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and six dependent areas, but HIV surveillance data is only mature enough at this point from 46 states and five dependent areas that represent 92% of all AIDS diagnosis through 2010. Along with HIV serologic surveys, HIV infection reporting and AIDS surveillance have served as the major resources to monitor and anticipate trends in HIV morbidity.

The initial AIDS surveillance case definition, which was established soon after the first reports of unexplained illnesses associated with cellular immunodeficiency in homosexual or bisexual men, formally listed the opportunistic infections and neoplasms indicative of underlying immunosuppression.13 In the absence of previously described causes of immunosuppression, a diagnosis of one of these conditions was defined as AIDS. The definition did not include the less severe manifestations of HIV infection and was designed to be highly specific and provide a standard means to monitor trends of severe immunodeficiency caused by what was then an unknown agent.

One of the initial uses of AIDS surveillance was to search medical records and death certificates retrospectively for previously unrecognized or unreported cases of similar immunodeficiency. This review identified only 125 cases of AIDS diagnosed between 1977 and 1981 and provided evidence that the condition was a new disease in the United States. Although a few isolated cases compatible with AIDS have been retrospectively diagnosed from the 1950s and 1960s, the AIDS epidemic in the United States essentially began in the late 1970s.14,15

The AIDS surveillance case definition was modified in 1985, 1987, 1993, and again in 2008.16–19 These revisions were made to reflect the development of serologic tests to detect HIV in 1985, the recognition of additional clinical illnesses associated with or directly caused by HIV infection in 1987 and changes in the clinical management of HIV- infected persons in 1993, and to have a single case definition for HIV infection that includes AIDS in 2008. Each revision to the AIDS surveillance case in the United States has been done in response to diagnostic and therapeutic advances and to improve standardization and compatibility of surveillance data regarding persons at all stages of HIV disease.

The 1985 and 1987 revisions added several new diseases to the AIDS surveillance definition for persons with diagnosed HIV infection. The 1985 revision included disseminated histoplasmosis, chronic isosporiasis, and certain types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. After this revision, the number of reported AIDS cases increased by an estimated 3% to 4%.20 The 1987 revision incorporated HIV encephalopathy, wasting syndrome, and other AIDS-indicator diseases that are diagnosed presumptively (i.e., without definitive laboratory evidence). As a result of this revision, an estimated additional 10% to 15% of HIV-infected persons became reportable as having AIDS, and AIDS cases increased by as much as 28% in some areas.21,22 The increase in AIDS case reporting resulting from these revisions was the greatest for women, blacks, Hispanics, and IDUs.21,22

In 1993, the AIDS surveillance definition was expanded to include evidence of severe immunosuppression (<200 CD4+ T-lymphocytes/µL or a CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of <14) as well as a series of clinical conditions that, in the presence of HIV infection, were considered AIDS defining (Table 121-1).

TABLE 121-1

AIDS-Defining Conditions

Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent*

Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs

Candidiasis, esophageal

Cervical cancer, invasive†

Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary

Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1-mo duration)

Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes)

Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)

Encephalopathy, HIV related

Herpes simplex, chronic ulcer(s) (>1-mo duration); bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis

Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1-mo duration)

Kaposi sarcoma

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia and/or pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia*

Lymphoma, Burkitt’s (or equivalent term)

Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term)

Lymphoma, primary, of brain

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, any site (pulmonary† or extrapulmonary)

Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

Pneumonia, recurrent†

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Salmonella septicemia, recurrent

Toxoplasmosis of brain

Wasting syndrome of HIV infection

* Children younger than 13 years.

† Added in the 1993 expansion of the AIDS surveillance case definition for adolescents and adults.

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Evaluation studies have shown that AIDS surveillance has provided complete and timely information on diagnosed cases of AIDS in the United States. A national multicenter study published in 1992 used computerized medical records in six areas to determine that 92% of persons with AIDS-defining conditions were reported to local health departments.23 Of these previously reported cases, 67% were reported to local health departments within 2 months of the date of diagnosis. Studies of state and local death certificate information and national vital statistics found that the completeness of reporting persons with AIDS ranged from 80% to 96% and that 70% to 90% of HIV-related deaths were reported to AIDS surveillance groups.24–26 Therefore, the reporting of AIDS in the United States has been among the most complete of all reportable diseases and conditions.27,28 However, advances in HIV treatment have slowed the progression of HIV disease for infected persons and contributed to a decline in AIDS incidence; as a result, many persons infected with HIV may never develop AIDS. Therefore, data from the AIDS reporting system, although still important, have become less informative about current trends in HIV transmission. This led public health authorities, in 1999, to recommend that all states and territories include surveillance for HIV infection and not just for AIDS.29 In addition, a revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection that incorporated the reporting criteria for HIV infection and AIDS into a single case definition was recommended by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists at its 1998 annual meeting and published by the CDC in 1999.30

As of April 2008, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and six dependent areas—American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Republic of Palau—have implemented the same confidential name-based reporting system to collect HIV and AIDS data. The analysis of data from states that have been conducting name-based HIV-AIDS surveillance for some time, and where the reporting system is now thought to be mature, suggests that the reporting of HIV infection in addition to AIDS case surveillance gives a better picture of recent trends in HIV transmission and assists efforts to better plan, implement, and evaluate HIV prevention and medical intervention programs.31,32 In addition, in line with more recent trends in HIV transmission, persons reported with HIV infection are more likely than those reported with AIDS to be women, adolescents, and racial and ethnic minorities.9,33

In the most recent revision of the surveillance case definition for adults and adolescents in 2008, the CDC required laboratory-confirmed evidence of HIV infection to meet the surveillance case definition. Diagnostic confirmation of an AIDS-defining condition alone without laboratory-confirmed evidence of HIV infection is no longer sufficient to classify an adult or adolescent as HIV infected for surveillance purposes. The incorporation of laboratory confirmation of HIV infection into the surveillance case definition is also consistent with the 2007 recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO).34 For laboratory confirmation of HIV infection, the revised surveillance case definition accepts a positive HIV antibody test (a screening test, such as enzyme immunoassay [EIA], confirmed by a supplemental test, such as a Western blot [WB]) or a positive HIV virologic test (such as the detection of HIV nucleic acid by polymerase chain reaction [PCR], HIV p24 antigen, or viral isolation). With the laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, cases are classified into one of four HIV infection stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, or stage unknown) (Table 121-2). In stage 1, the person has no AIDS-defining conditions and either a CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count of greater than or equal to 500 cells/µL or a percentage of greater than or equal to 29. In stage 2, there are no AIDS-defining conditions, and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count is between 200 and 499 cells/µL or a percentage between 14 and 28. Stage 3 corresponds to AIDS; the patient has a CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count of less than 200 cells/µL (or a percentage <14) or documentation of an AIDS-defining condition. Finally, when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count is not available or there is no information of an AIDS- defining condition, the patient is classified as HIV infected, stage unknown. For children younger than 18 months, the revised surveillance case definition incorporates newly available testing technologies and classifies cases into definitively HIV infected, presumptively HIV infected, presumptively uninfected with HIV, and definitively uninfected with HIV. One must stress that the revised case definition is intended for public health surveillance and not for clinical diagnosis.

TABLE 121-2

Surveillance Case Definition for HIV Infection among Adults and Adolescents (Aged ≥ 13 years): United States, 2008

| STAGE | LABORATORY EVIDENCE* | CLINICAL EVIDENCE |

| Stage 1 | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of ≥500 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of ≥29 | None required (but no AIDS-defining condition) |

| Stage 2 | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of 200-499 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of 14-28 | None required (but no AIDS-defining condition) |

| Stage 3 (AIDS) | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of <200 cells/µL or CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of <14† | or documentation of an AIDS-defining condition (with laboratory confirmation of HIV infection)† |

| Stage unknown§ | Laboratory confirmation of HIV infection and no information on CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or percentage | and no information on presence of AIDS-defining conditions |

* The CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage is the percentage of total lymphocytes. If the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and percentage do not correspond to the same HIV infection stage, select the more severe stage.

† Documentation of an AIDS-defining condition supersedes a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of ≥200 cells/µL and a CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes of ≥14. Definitive diagnostic methods for these conditions are available in Appendix C of the 1993 revised HIV classification system and the expanded AIDS case definition. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep.1992;41[RR-17]):1-19; and National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/epo/dphsi/casedef/case_definitions.htm.)

§ Although cases with no information on the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count or percentage or on the presence of AIDS-defining conditions can be classified as stage unknown, every effort should be made to report CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts or percentages and the presence of AIDS-defining conditions at the time of diagnosis. Additional CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts or percentages and any identified AIDS-defining conditions can be reported as recommended. (Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Laboratory Reporting of Clinical Test Results Indicative of HIV Infection: New Standards for a New Era of Surveillance and Prevention [Position Statement 04-ID-07]. 2004. Available at http://www.cste.org/ps/2004pdf/04-ID-07-final.pdf.)

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

From Schneider E, Whitmore S, Glynn KM, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged < 18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years—United States, 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-10):1-12.

HIV Infection and AIDS in Adults

Incidence and Prevalence of AIDS and HIV in the United States

More accurate estimates of HIV prevalence are now possible, with 80% of the states reporting name-based HIV diagnoses since January 2006. The CDC estimates that 1.2 million persons were living with diagnosed or undiagnosed HIV infection in the United States at the end of 2008, for an overall HIV prevalence of 417.5 per 100,000 population.35 The majority of those living with HIV were nonwhite (65%), and nearly half (48.1%) were MSM. The HIV prevalence rates for blacks (1715 per 100,000) and Hispanics (585 per 100,000) were, respectively, 7.6 and 2.6 times the rate for whites (224 per 100,000). Since 1981, when the first cases were reported in the United States,1,2 the number of persons with AIDS increased rapidly, with the first 100,000 AIDS cases reported during an 8-year period (1981 to 1989), whereas the second 100,000 cases were reported in just more than 2 years (1989 to 1991).36

In the early 1990s, the number of persons reported with AIDS in the United States increased substantially, in part because of expansion of the surveillance definition for AIDS,18 primarily the inclusion of markers for severe HIV-related immunosuppression. Because of this expansion, the number of reported AIDS cases increased by more than 100% in 1993 versus 1992.37 After the introduction of highly active ART, the number of deaths and new AIDS cases began to decline for the first time in the history of the epidemic.34,38 Between 1995 and 1998, the annual number of new AIDS cases fell by 38% (from 69,242 to 42,832) and deaths by 63% (from 51,760 to 18,823). In 2010, the number of AIDS diagnoses in the United States and six dependent areas was 19,241, with an estimated rate of AIDS diagnoses of 10.8 per 100,000 population. Sixty-five percent of these AIDS diagnoses were among blacks and 53% among MSM. In 2009, there were 13,179 deaths from AIDS.39

Because of this dramatic drop in mortality from AIDS resulting from the use of ART, the number of persons living with AIDS in the United States has increased. At the end of 2009, an estimated 476,732 persons were living with AIDS in the United States.

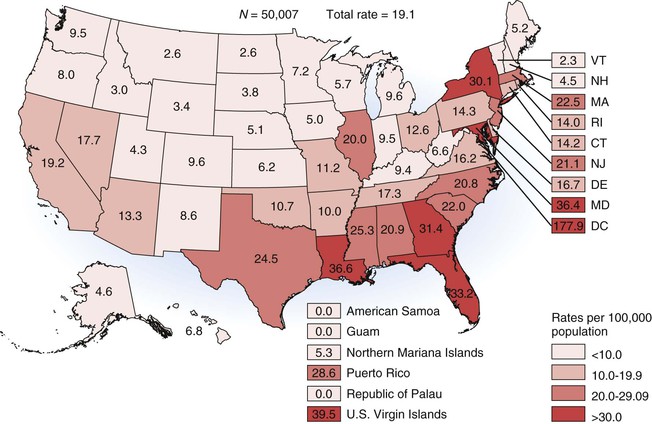

In 2008, the CDC published the first national HIV incidence estimates, using novel laboratory assays that differentiate recent versus long-standing HIV infection.40 This analysis showed that an estimated 56,300 new HIV infections (95% confidence interval [CI], 48,200 to 64,500) occurred in 2006, for an overall incidence rate of 22.8 cases per 100,000 population.11 The revised number of new infections is substantially higher than the previous estimate of 40,000 annual new infections in the United States.41 Seventy-three percent of new infections occurred among men, 45% among blacks, and more than half (53%) among MSM. As methods to calculate incidence have been improved, the CDC now estimates that there were 48,600 individuals who were infected with HIV in 2006; 56,000 in 2007; 47,800 in 2008; and 48,100 in 2009.42 In each year, most of the new infections (>755%) occurred among males and blacks (>42%). From 2006 to 2009, there was no significant increase in HIV incidence in the United States, except among young persons (aged 13 to 29 years). In this group, MSM made up greater than 60% of new infections. Furthermore, young black men experienced the largest increase in HIV incidence, from 5300 new infections in 2006 to 7600 in 2009, a 43% increase. The rate of diagnoses of HIV infection among adults and adolescents in 2011 in the United States and six dependent areas was 19.1 per 100,000 population and varied from a high of 177.6 in the District of Columbia to 0.0 in American Samoa, Guam, and the Republic of Palau (Fig. 121-1).

Significant increases in HIV testing have occurred in recent years. The CDC estimated in 2008 that 44.6% of persons aged 18 to 64 have never been tested for HIV infection,43 and the percentage of HIV-positive persons who were undiagnosed decreased from approximately 25% in 2003 to less than 20% in 2009.

Serologic Monitoring of the HIV Epidemic

Because AIDS is the most advanced manifestation of HIV infection, the period between infection with HIV and the development of AIDS is long, and substantial changes in the natural history of HIV infection have occurred as a result of the availability of highly active ART, surveillance systems that only monitor AIDS cases have become less relevant than in the past. As a result, various methods have been used periodically to estimate the prevalence and incidence of HIV infection over the course of the epidemic.

HIV seroprevalence surveys have been the standard means to describe the patterns of current HIV transmission. These surveys have been conducted on (1) specimens not linked to personal identifiers and collected for other purposes, (2) name-identified specimens, and (3) specimens collected from populations subject to routine or mandatory HIV screening, such as blood donors or military personnel. In addition, in 2003, the CDC implemented the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System (NHBS) to estimate and monitor HIV behaviors, prevalence, and trends. This survey is conducted in rotating annual cycles, with each one of three risk groups (MSM, IDUs, and high-risk heterosexuals) surveyed each year. In general, the patterns of HIV transmission observed in these studies in the United States are similar to those observed through AIDS case surveillance—higher rates of HIV infection are found among men than women, among blacks and Hispanics than whites, and among persons 20 to 45 years of age than those in other age groups. In 2005, the CDC recommended that all states and U.S. dependent areas adopt confidential name-based reporting of HIV infection. Because different states have adopted this recommendation at different times, the robustness of the data varies. However, 51 areas (46 states and five dependent areas) have had confidential named-based HIV infection reporting since at least 2003, which allows stabilization of data collection and adjustment of the data to monitor trends.39 These 46 states represent approximately 92% of AIDS diagnosis in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. At the end of 2009, an estimated 784,701 persons were living with diagnosed HIV infection in these 46 states, 74% were male, 43% were black, and 68% of infections were attributed to male-to-male sexual contact. The highest incidence remains among MSM, which peaked in the early 1980s (5 to 20/100 person-years) and then declined but remained high during the 1990s (2 to 4/100 person-years).41 In addition, the most recent estimates demonstrated that HIV infection disproportionately affects blacks, with a rate that is seven times higher among blacks (incidence rate, 83.7/100,000) and almost three times higher in Hispanics (29.3/100,000) than whites (11.5/100,000).11 It is estimated that approximately 0.7% of men and 0.2% of women between the ages of 18 and 49 years are infected in the United States. However, the prevalence is much higher for blacks, in whom 2% of men and 0.6% of women are estimated to be infected. The most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) reported that the prevalence of HIV infection among adults aged 18 to 49 years residing in households in the United States was 0.47% for the period 1999 to 2006.44 Although the number of persons who are being tested for HIV has increased in the United States, the denial of HIV risk factors and the fear of being HIV positive continue to be major reasons for not being tested for HIV.45

Homosexual and bisexual men remain a major population with an increased prevalence of HIV infection. In surveys conducted primarily in sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics in the early to mid-1980s, HIV seroprevalence rates in homosexual and bisexual men ranged from 10% to 70%, with most rates falling between 20% and 50%.46 Although the highest rates were found in New York City and San Francisco, areas of moderate-to-high HIV seroprevalence are dispersed throughout the country.46 In 1997, a study of unlinked serologic specimens collected from homosexual and bisexual men attending STD clinics in 17 cities had a median seroprevalence rate of 19.3%, with rates among black men approximately twice those of white MSM.47 That same year, a probability sample of MSM in 4 large U.S. cities demonstrated an overall HIV seroprevalence of 17%; however, the prevalence was 29% among blacks and 42% among those who injected drugs.48 Among homosexual and bisexual men attending STD clinics from 1988 to 1992, the overall HIV seroprevalence was 33% (range, 5% to 52%).49 Between 1989 and 1999, the cumulative HIV prevalence in 4 STD clinics in the western United States among MSM ranged from 13% in Seattle to 30% in San Francisco and declined a mean of 2.1% (95% CI, 1.6 to 2.6) to 2.8% (95% CI, 2.6 to 3.1) per year.50 The HIV seroprevalence decline seen in this population over time was particularly significant among white homosexual and bisexual men (from 32% in 1989 to 22% in 1992), suggesting a decrease in the incidence of HIV infection.51 The incidence of HIV infection among homosexual and bisexual men in some cohort studies dropped in the mid- to late 1980s.46,52 However, more recent studies in young MSM suggest the continued high incidence of HIV. Data from the Young Men’s Survey conducted in 7 U.S. cities between 1994 and 1998 demonstrated an overall prevalence of HIV infection of 7.2%, ranging from 3.3% among whites to 14.1% among blacks. In that same study, HIV incidence overall was 2.6%, but it was 3.5% among persons aged 20 to 22 years, 4.0% among blacks, and 5.4% among men of mixed races.53 In the most recent NHBS cycle of survey among MSM, the overall HIV prevalence was 19%, but it was 28% among black MSM, 18% among Hispanic MSM, and 26% among white MSM. The estimated number of newly reported HIV infections among MSM increased by 12% from 26,700 in 2008 to 29,800 in 2010, and the majority of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses are occurring among racial and ethnic minority men, particularly black MSM.54 The increase in the incidence of new HIV infections among MSM may be due to continued high-risk behavior in this population.55,56 The role of ART in the increase of risk-taking behavior among MSM is still controversial, but data suggest that persons on ART are more likely to develop sexually transmitted infections, an epidemiologic marker of unsafe sex.57 In addition, the increase of HIV resistance to antiretroviral drugs among persons with recent infection suggests that their infections are being acquired from persons who are known to be HIV infected and receiving therapy.58

In contrast to the epidemic among homosexual and bisexual men, the epidemic among IDUs has been more concentrated geographically within the United States. Among IDUs, the initial HIV seroprevalence studies demonstrated very high rates of HIV infection in the Northeast and along the Atlantic Coast and low rates on the West Coast and in cities in other areas.46,59,60 Although the highest rates of HIV infection continue to be observed in northeastern cities, the rate of HIV infection among IDUs in other cities has increased. Studies conducted in the late 1980s in Atlanta, Chicago, and Baltimore showed an HIV seroprevalence rate of greater than 12%.61–63 Surveys conducted in drug treatment centers in 1997 showed a median HIV seroprevalence rate of 14.8% (range, 0% to 37.7%) among IDUs entering drug treatment programs.47 Similar findings have been noted in subsequent studies: HIV seroprevalence among IDUs admitted to drug treatment centers in Baltimore (25%) and Newark (24%) was high, whereas it was low in San Francisco (7%), Seattle (5%), Denver (2%), and Detroit (1%).64–66 However, among most large metropolitan areas, the HIV prevalence rates among IDUs continues to be less than 10%, and approximately 40% have a prevalence of less than 5%.67 The incidence of HIV also has significant geographic variation, remaining higher in the East (1 to 3/100 person-years) and lower in the West (<0.5/100 person-years) United States.43 The number of new HIV infections attributed to injection drug use in the United States has decreased in recent years. Despite this, 9% of new HIV infections in 2009 occurred among IDUs.39

The reasons for the geographic differences in HIV seroprevalence among IDUs remain poorly understood, inasmuch as cities with low prevalence rates have many IDUs who practice high-risk behaviors.66 In addition, the HIV epidemic among IDUs is closely related to other high-risk behaviors, such as having unprotected sex, which frequently occurs in the context of illicit-substance use.67,68 Studies in STD clinics have also shown elevated rates of HIV infection among heterosexual IDUs compared with other heterosexual men and women.49,51 Although heroin injection is typically associated with the parenteral transmission of HIV, injectors of cocaine and other drugs also have increased rates of HIV infection.63–71 Cocaine injection, especially the use of “speedballs” (cocaine or amphetamines with heroin), injection in a “shooting gallery,” and sexual-risk behavior are associated with HIV infection among IDUs.71,72 Data from New York City suggest that HIV prevalence among drug users declined between 1991 and 199673 and indicate that changes in HIV prevalence among sex and needle-sharing partners or changes in risk behavior with such partners might lead to changes in the risk for new infections among drug users.

Certain populations of heterosexual men and women who do not inject drugs also have appreciable rates of HIV infection. From 1988 to 1989, studies conducted in STD clinics with heterosexual persons who do not inject drugs but have other STDs found a median seroprevalence of 2.3%, with a range of 0% to 14%.51 Although the men in these clinics typically had higher rates than women, in some areas, adolescent females had higher rates of HIV infection than adolescent males. Nearly one third of those infected heterosexually are estimated to have been infected as adolescents.74

HIV infection acquired through heterosexual contact is the source of an increasing number of AIDS cases, especially among women, particularly those who are members of minority groups.75,76 Despite this, the number of reported cases of HIV/AIDS attributable to high-risk heterosexual contact has remained constant or has declined during the current decade for both men and women. Of those persons infected heterosexually, sexual contact with an IDU is the most frequently reported risk. Accordingly, the geographic distribution of HIV rates among persons who acquired their infection through heterosexual contact and among IDUs is similar.77 In addition, persons who use smokable forms of cocaine (“crack” cocaine) and other noninjected illicit drugs have elevated risks for HIV infection as a result of exchanging sex for drugs or money and the presence of other STDs.72,78–81 Some persons infected through heterosexual contact may not report a risk of HIV infection because they are unaware of the serostatus of their heterosexual partners.35,51,78 However, the incidence among heterosexual men and women continues to be much lower than that among MSM. In a study conducted among clients of STD clinics in the United States between 1990 and 1999, the incidence of HIV among heterosexual men and women was estimated to be 0.5% compared with 7.1% among MSM.82

Female commercial sex workers (prostitutes) are at increased risk for HIV infection because of injection drug use and multiple sex partners. In a 1987 multicenter study of prostitutes in various settings in selected cities, 65 (10%) of 670 women tested positive for the HIV antibody.83 The seroprevalence rates for HIV infection ranged from 0% for prescreened prostitutes in Nevada to 69% for prostitutes being treated for drug addiction in New Jersey. Among the prostitutes who were studied, the major risk factor was injection drug use. In a study in south Florida in 1987, 37 (41%) of 90 inner-city sex workers were positive for the HIV antibody, including 29 (46%) of 63 women who reported drug use and 8 (30%) of 27 women who denied using drugs.84 From 1987 to 1991, the prevalence of HIV infection among female sex workers in southern Florida remained relatively stable at approximately 24%. However, the incidence of HIV infection among female sex workers in this area who received multiple HIV tests increased from 0.3% per 100 person-years in 1987 to 15% in 1991.85 The data from a cohort study conducted among drug users in Baltimore, a high-incidence and high-prevalence city, suggest that the incidence of HIV is doubled among drug-using men who also engage in homosexual sex and among women who have had a recent sexually transmitted infection, suggesting that sexual behavior is a major determinant of risk even among drug users.86

Surveys conducted in some clinical settings indicate that the HIV infection rate is higher than it is in a more representative sample of the general population.87–91 In a survey conducted from 1989 to 1991 of persons admitted to 20 hospitals, an HIV seroprevalence of 4.7% (range, 0.2% to 14.2%) was observed; in one hospital, 24% of men 15 to 54 years of age were infected with HIV.87 The data from this survey were used to estimate that 225,000 HIV-infected persons were hospitalized in 1990; 72% of them were admitted for conditions other than HIV infection or AIDS. A survey conducted from 1990 to 1992 of patients seen in primary care practices revealed an HIV seroprevalence rate of 0.45%, with the rate among men (0.96%) being higher than that among women (0.22%).88 Voluntary routine HIV counseling and testing among inpatients in a hospital in Boston was able to demonstrate an HIV seroprevalence of 3.8% among patients who otherwise would not have been tested for HIV, suggesting that a substantial number of patients with undiagnosed HIV are being discharged from health care facilities without HIV infection being considered.89

In many areas, tuberculosis patients have high rates of HIV infection, and HIV screening should be provided to all those diagnosed with tuberculosis.90 Among 27 tuberculosis treatment clinics in 15 metropolitan areas surveyed between 1988 and 1995, HIV seroprevalence ranged from 0.6% to 42.9%, with a median rate of 8.9%.91 The highest rates were found in the Northeast and Atlantic Coast areas and among U.S.-born persons 30 to 39 years of age, who had a median seroprevalence of 30.1%. High rates were also noted among those with extrapulmonary disease. A review of the prevalence of HIV among persons newly diagnosed with tuberculosis in Los Angeles County between 1993 and 1996 demonstrated an overall prevalence of 10.8%, with the highest prevalence rates seen among persons born in the United States (15.7%), males (14.1%), blacks (14.3%), and those aged 30 to 44 years (14.4%).92

Among patients with syphilis, the overall HIV seroprevalence was 15.7%; among men, the seroprevalence was 27.5% and among women 12.4%.93 However, among MSM and those with syphilis, the seroprevalence ranged from 64.3% to 90%.

HIV prevalence rates among adolescents attending adolescent medicine clinics in three metropolitan areas (Baltimore, Houston, and New York City) that collected data each year from 1993 to 1997 showed an overall HIV prevalence rate of 0.4% (range, 0.2% to 0.5%).94 The rates were the same for male and female patients (0.4%) and were approximately the same among patients 13 to 19 years of age (0.4%) and those 20 to 24 years of age (0.5%). However, the rates were higher among black patients (0.6%) than among Hispanic and white patients (0.1%).

Studies of HIV seroprevalence in entrants to correctional facilities have indicated a wide range of rates, with the highest in areas with a moderate-to-high incidence of AIDS.95 From 1991 to 1992, the median HIV seroprevalence was 2.9% (range, 0% to 15%) in 35 correctional facilities in 17 metropolitan areas.62 The rates ranged from 1% to 12.5% for men and 0% to 24% for women, which is a reflection of the high rates of drug use in these persons. Among entrants to the New York state prison system between 1987 and 1997, 12% of men and 18% of women were infected with HIV.96 Between 1992 and 1998, data from nearly 500,000 HIV tests performed in correctional facilities in the United States demonstrated an overall HIV seroprevalence of 3.4%, 56% of which were among persons newly identified as HIV infected.97

HIV seroprevalence data are more available for large groups who are routinely tested for HIV infection. These groups include blood donors, applicants for military service, military personnel, and applicants to U.S. Department of Labor Job Corps training programs.62,94,98–105 These surveys are valuable but limited in generalizability in that many persons at risk for HIV infection are excluded from some populations (e.g., potential blood donors and military applicants). A study of five blood banks conducted between 1991 and 1996 showed that the prevalence of HIV decreased in first-time donors from 0.030% to 0.015%.106 Approximately 8 million persons voluntarily donate 14 million units of blood annually in the United States. Trends in the prevalence of HIV can be best determined from first-time blood donors, who represent approximately 20% of all donations. Since 1985, the American Red Cross, which collects approximately half of the voluntary donations, has provided the CDC with routine HIV screening results from their blood donations. After a slight increase from 1993 to 1994 among men, prevalence then decreased from 0.032% in 1994 to 0.021% in 1997. Among women, prevalence was relatively stable (0.010% to 0.014%) between 1993 and 1997.94 In 2002, the prevalence of HIV among donors was 0.012%. Controlling for age, HIV prevalence was higher among donations from first-time male donors than first-time female donors (0.0171% vs. 0.0070%) and higher from repeat male donors than repeat female donors (0.0013% vs. 0.0006%).107 The prevalence of HIV among first-time donors decreased by 0.00026% per quarter between 1995 and 2002. HIV prevalence decreased among first-time male and female donors of most age groups except for that among first-time male donors 30 to 39 years of age in whom HIV prevalence had appeared to have increased since 2000 (P = .0525).107

The overall prevalence of HIV infection among 2.3 million applicants for military service was 1.31 per 1000 between October 1985 and September 1989.98 The HIV infection rates in this population were higher for men (1.42/1000) than women (0.66/1000), for black non-Hispanic men (3.7/1000) than white men (0.61/1000), and for persons from large metropolitan areas, particularly those with higher rates of AIDS case reporting. The seroprevalence rate among teenage military applicants (0.34/1000) was lower than the median rate for all applicants, the male-to-female ratio was nearly 1 : 1, and the rate of infection among 17- and 18-year-old females exceeded that of males of the same age.99 The overall prevalence of HIV infection in applicants decreased from approximately 0.15% in 1985 to 0.045% (1 positive for every 2200 applicants tested) in 1997.47 The rates were particularly high for black male military applicants (0.17%).94 Because applicants who are HIV-positive drug users and homosexuals are not accepted into the military, a self-selection bias among persons in high-risk categories may occur; therefore, certain populations may be underrepresented among military applicants.47

Among U.S. Army active-duty personnel, the HIV incidence rate was 0.17/1000 person-years between 1985 and 1999.103 The incidence rate for male and female soldiers was 0.18/1000 person-years and 0.08/1000 person-years, respectively. The rate of seroconversion decreased from 0.49/1000 person-years from 1985 to 1987 to 0.29/1000 person-years from 1988 to 1989.96 However, a reduction in the seroconversion rate was not observed for black soldiers, suggesting a higher rate of continued transmission in this population.

Students who enter Job Corps training programs tend to be economically disadvantaged school-aged youths drawn from racial and ethnic minority communities in both rural and urban areas. For students aged 16 to 21 years who entered training from January 1990 through December 1996, 2.3 per 1000 were infected with HIV, a rate of almost 10 times that seen among applicants for military service, with statewide prevalence rates ranging from 0% to 0.8% in 1997.47,105 Among Job Corps applicants, the infection rate increased with age. HIV prevalence was higher for women than men (2.8/1000 vs. 2.0/1000). HIV seroprevalence rates were the highest for black women (4.9/1000). From 1990 through 1996, the HIV prevalence rates for women and men declined from 2.8 per 1000 in 1990 to 1.4 per 1000 in 1996. The highest rates were observed in students from large Northeast urban centers and also among students from rural and smaller urban centers in the South. In 1997, HIV prevalence was 0.26% for Job Corps entrants from the South, 0.20% from the Northeast, 0.11% from the Midwest, and 0.01% from the West.94

Another type of broad population survey was for childbearing women, which provided unbiased population-based estimates of HIV infection in women giving birth in the United States. HIV antibody prevalence for childbearing women was ascertained by blinded surveys conducted on residual blood samples collected on filter paper from newborns for routine metabolic screening, such as that for phenylketonuria.108 HIV seroprevalence among childbearing women remained stable nationwide from 1987 through 1994 at values ranging from 1.5 to 1.7 per 1000 women.109 Seroprevalence decreased over this time in the Northeast and increased in the South. In 1994, HIV seroprevalence rates among black childbearing women were 2 to 20 times higher than those among white women. The findings of seroprevalence studies of women seeking reproductive care services have also shown the highest HIV rates to be in clinics located along the Atlantic Coast and in Puerto Rico.47,110 If HIV seroprevalence rates among childbearing women were similar for all women of reproductive age in the United States, in 1994, approximately 84,000 women in this age group would have been infected with HIV.108 The survey of childbearing women was halted in 1995 in light of congressional concerns about blinded surveys in this population.

As previously stated, although surveillance for HIV infection has traditionally focused on the incidence of AIDS and the prevalence of HIV, new diagnostic technologies that allow the estimation of incident HIV infection have become available, including the use of the sensitive–less sensitive EIA test (or the serologic testing algorithm for recent HIV seroconversion [STAHRS]) and the measurement of HIV-ribonucleic acid (RNA) by PCR in pooled blood specimens that test negative for HIV (see Chapter 122).40,111 Having an HIV surveillance system that focuses on incident rather than prevalent infections undoubtedly allows better monitoring of the HIV epidemic.112

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree