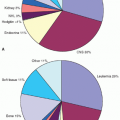

Fig. 1.2

Trends in incidence of prostate cancer in selected countries: age-standardised rate (W) per 100,000 [2]

Fig. 1.3

The 20 most common cancers in 2010, number of new cases, UK (UKCIS, accessed August 2013, http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org)

Fig. 1.4

The ten most common cancers in males in 2010, numbers of new cases, UK (UKCIS, accessed August 2013, http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org)

Prostate cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in men in the UK with 10,793 deaths recorded in 2011 [4]. The association between prostate cancer and age continues to be observed in mortality figures with 73% prostate cancer deaths occurring in men 75 years or older [4]. Overall however, there has been a steady increase in the 5-year relative survival rates in recent years from 73.4% (1999–2001) to 83.4% (2005–2007). It is likely that this is due to earlier detection and advances in treatment modalities (Fig. 1.5) [5].

Fig. 1.5

Trends in age-standardised mortality rates, breast (females) and prostate cancer, UK, 2002–2011 (UKCIS, accessed March 2014, http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org)

Prostate cancer screening has now been adopted in a number of Westernised countries resulting in some cancers being detected at earlier stages. These may often be clinically insignificant, lower-risk cancers, potentially resulting in overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment for some patients [6]. At present PSA screening has not been adopted in the UK.

1.2 Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing prostate cancer are yet to be well characterised but include ethnic origin, older age and heredity [2]. The incidence of prostate cancer is known to vary with race (Table 1.1). Patients of African or Afro-Caribbean origin have higher prostate cancer incidence compared to any other racial group. These patients also suffer worse outcomes from prostate cancer compared to Caucasian patients [7, 8]. The reasons for such disparities in incidence and outcomes may be related to variations in tumour biology or in delayed presentation as is often observed [9, 10].

Table 1.1

Number of cases of prostate cancer by major ethnic group (including unknown), England, 2006–2010 (National Cancer Intelligence Network, March 2014)

Ethnic group | Number of prostate cancer cases |

|---|---|

White | 149,549 |

Asian | 2308 |

Black | 4905 |

Chinese | 177 |

Mixed | 511 |

Other | 959 |

Unknown | 7927 |

Total | 166,336 |

Other risk factors include age with the risk of developing prostate cancer increasing nearly exponentially with increasing age [11]. Family history of prostate cancer, in particular younger age at diagnosis in first-degree relatives, is also associated with an increased incidence. In some cases no associated mutation is identified; however in approximately 2% of patients with prostate cancer and age ≤55 years, this may be due to a mutation in the ‘breast cancer 2’ (BRCA2) gene. Additionally, prostate cancer among BRCA2 carriers has been shown to be aggressive, with poorer survival rates observed [12]. The roles of inflammation, sexually transmitted diseases [13], obesity, dietary fat intake [14], vitamin D level [15], genetics, environment, testosterone and oestrogen effects warrant further investigation and remain unclear [11].

1.3 Clinical Presentation

The clinical symptoms of localised prostate cancer usually relate to an enlarged prostate gland resulting in lower urinary tract symptoms. These include increased frequency of micturition (frequency) especially at night (nocturia), urgency, hesitancy to pass urine and poor urinary stream occurring commonly. In addition patients may experience dysuria and more rarely haematuria/haematospermia. In some cases symptoms related to metastatic disease can be the presenting complaint; these include fatigue, loss of appetite, bone pain and back pain. Patients with a large burden of metastatic bone disease are at risk of malignant spinal cord compression with clinical symptoms of weakness and paraesthesia’s in the legs, urinary retention and constipation often observed.

1.4 Diagnosis

Prostate cancer is usually initially investigated with a DRE and PSA levels. These findings along with age, ethnicity, co-morbidities, family history and previous prostate history are then used to decide on the need for prostate biopsy [16].

Prostate biopsy is most commonly performed under transrectal ultrasound guidance with antibiotic cover. Adequate sampling of the prostate gland usually requires a minimum of eight cores. Definitive diagnosis is based on the presence of adenocarcinoma in the specimens taken. The most dominant Gleason pattern and the pattern with the highest Gleason grade determine the Gleason score [17]. This score and the maximum cancer length should be reported for each core. Historically a transrectal approach is used; however some urologists now prefer a transperineal approach. The cancer detection rates from transperineal biopsies are comparable to those obtained from a transrectal approach without the associated risk of sepsis [18, 19].

1.5 Staging Procedures and Investigations

Local clinical tumour staging is often supplemented with an MRI scan which can help to identify those patients in whom a nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy can be carried out [16]. Current guidelines recommend staging evaluations for patients at higher risk for asymptomatic metastatic disease or locally advanced disease that would alter local therapy recommendations. The clinical guidelines do not recommend staging for most patients with favourable disease characteristics because imaging studies are unlikely to reveal metastatic disease [20, 21]. The 2009 TNM prostate cancer staging classification is shown in Table 1.2 [22]. Moreover, general health and co-morbidities should be assessed, and patients who are not considered suitable for treatment with curative intent due to poor general health may not require staging investigations.

T | Primary tumour |

TX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

T1 | Clinically inapparent tumour not palpable or visible by imaging |

T1a | Tumour incidental histological finding in 5% or less of tissue resected |

T1b | Tumour incidental histological finding in more than 5% of tissue resected |

T1c | Tumour identified by needle biopsy (e.g. because of elevated PSA level) |

T2 | Tumour confined within the prostate |

T2a | Tumour involves one half of one lobe or less |

T2b | Tumour involves more than half of one lobe, but not both lobes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|