FIGURE 32.1 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A retrograde cholangiogram is performed with the duodenoscope in a “hockey-stick” configuration in the second portion of the duodenum. This patient is a 53-year-old woman with idiopathic CP and jaundice. She has segmental narrowing in the intrapancreatic segment of the bile duct consistent with a CP–induced bile duct stricture.

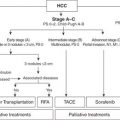

ERCP IN THE SETTING OF PERIAMPULLARY MALIGNANCY

With improvements in cross-sectional imaging and EUS, the role of ERCP for the diagnosis of periampullary malignancy (distal cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [PDAC], in particular) is increasingly limited. ERCP remains the procedure of choice for biliary drainage, if indicated, and is a medium for obtaining tissue samples.

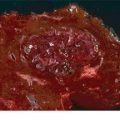

Periampullary malignancies may present with a bile duct stricture that can be challenging to distinguish from a benign bile duct stricture, such as from CP. Malignant biliary strictures often have a length greater than 10 mm, a ragged contour, fixed filling defect, and/or shouldering above the stricture (abrupt transition in appearance from normal to stricture) (Fig. 32.2). The malignant potential of proximal common hepatic duct or bifurcation strictures is generally higher than that of distal bile duct strictures, often due to cholangiocarcinoma or portal lymphadenopathy causing extrinsic compression.

FIGURE 32.2 Malignant distal bile duct stricture. A 63-year-old woman presented with painless jaundice and was found to have a pancreatic head mass on EUS performed immediately prior to ERCP. EUS–FNA confirmed the presence of PDAC. Retrograde cholangiogram reveals a discrete common bile duct stricture with abrupt “shouldering” of the upstream, dilated common hepatic duct. This cholangiogram is highly suggestive of a malignant bile duct stricture, as in this case.

Tissue Sampling

ERCP-based tissue sampling is usually performed with a cytologic brush or forceps biopsies. The sensitivity of cytologic brushings from bile duct strictures is approximately 30% to 40% and specificity approaching 100%. Brush cytology in primary biliary tumors has a higher sensitivity than in extrinsic tumors (pancreatic or metastatic) (80% vs. 35%). Fewer studies have addressed the yield of cytologic brushings of pancreatic ducts. The accuracy is estimated to be 72%, and using a technique of collecting pancreatic juice above a stricture, a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 100%, respectively, can be obtained. However, risks of pancreatitis and hemorrhage in the upstream pancreatic duct should be considered. In patients with PSC, diagnosing malignancy can be difficult, and cholangiography increases the specificity and positive predictive value for cholangiocarcinoma when combined with tumor markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9) and cross-sectional imaging. There is no clinically significant difference in diagnostic yield between cytologic brushes produced by different manufacturers.

The sensitivity of forceps biopsy ranges from 43% to 88% with specificity similar to brush cytology (approaching 100%). Flexible forceps permit easier biliary cannulation than do stiffer ones. The combination of cytologic brushing and forceps biopsy increased sensitivity by 15% in one report but a smaller benefit in another study. Another study found that combination of cytologic brushing, forceps biopsy, and endoscopic fine needle aspiration was more sensitive (73% to 77%) than was each approach alone. Aspiration of bile for cytologic analysis is rarely used because of low sensitivity of 6% to 32%.

In some cases, methods such as digital image analysis (DIA) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) can improve the sensitivity of cytology alone. DIA quantifies the amount of cellular DNA by measuring the intensity of nuclei stained with a dye that binds to nuclear DNA. FISH uses a fluorescently labeled probe to detect chromosomal abnormalities in cells. FISH increases sensitivity of cytology to a greater degree than does DIA. However, there is the potential for false positives with either technique, particularly in cases of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Therefore, a positive FISH alone in the absence of a positive cytology specimen needs to be considered with the rest of the clinical picture.

Miniature endoscopes can be used to visualize the bile (cholangioscopy) and pancreatic (pancreatoscopy) ducts. Traditional mother–daughter systems required two operators to maneuver the duodenoscope and the cholangioscope independently. A single-operator, fiberoptic cholangioscope (Spyglass, Boston Scientific Corp.) is available; while this facilitates direct visualization of the bile and pancreatic ducts, its impact on confirming the presence or absence of malignancy remains unclear.

TREATMENT OF JAUNDICE

The location of malignant biliary obstruction influences the efficacy of endoscopic biliary drainage (distal better than perihilar). The endoscopic management of proximal bile duct strictures (bismuth II–IV) and bile duct obstruction are not discussed in this review. ERCP is typically preferred to percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) for biliary drainage because an external drain is avoided. The short-term (<90 day) success of ERCP in achieving biliary drainage in the setting of distal bile duct obstruction is 80% to 90%. Complications may occur in up to 10% of patients, including cholangitis, perforation, bleeding, and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Plastic biliary stents are relatively inexpensive and easily removable compared to self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS). However, SEMS have a larger diameter (8 to 10 mm as opposed to 7 to 10 Fr for plastic) and are thus less likely to occlude prematurely (median patency rates of 6 to 9 months for SEMS as compared to 3 months for plastic stents).

In patients with locally advanced or metastatic PDAC, the goals of biliary drainage are palliation of symptoms and to permit systemic chemotherapy with a normal or near-normal serum bilirubin. The treatment of jaundice will undoubtedly relieve pruritus (if present) and may improve other symptoms such as anorexia and indigestion. For cases of unresectable disease, an endoscopic approach is safer than is surgical bypass but with reduced durability. Long-term patency of SEMS is superior to that of plastic stents due to their larger diameter; SEMS should be placed in patients having a life expectancy of greater than 3 months. The majority of patients in the United States with potentially resectable periampullary malignancy undergo preoperative biliary drainage despite a lack of evidence that it reduces postoperative complications. This practice may be explained in part by a delay in surgical consultation and concern for higher risk of perioperative complications in the setting of jaundice. Older studies suggest jaundice may be a predictor of postoperative infection and renal and nutritional complications. Experimental studies demonstrate improved nutritional status and immune function and reduced endotoxinemia after biliary decompression. Prospective studies evaluating the role of preoperative biliary drainage have excluded patients with deep jaundice (serum total bilirubin ≥10 to 15 mg/dL), where the benefits of drainage are expected to be the highest. Furthermore, the duration between preoperative biliary drainage and surgery is often less than 4 weeks despite evidence suggesting normalization of hepatocyte function after 6 weeks of decompression.

Treatment of Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Duodenal obstruction from pancreatic cancer typically is not present at diagnosis but may develop in 15% to 20% of patients. To avoid this complication, many surgeons create a prophylactic palliative gastrojejunostomy with a biliary bypass in those who are deemed to be unresectable at exploration. Endoscopic placement of a self-expandable, gastroduodenal metallic stent has lower morbidity compared to surgical gastrojejunostomy and comparable short-term efficacy but lower long-term (>3 to 6 months) efficacy due to tumor ingrowth within the interstices of the stent. In a study comparing patients who underwent surgical gastrojejunostomy with endoscopic stenting, patients who underwent endoscopic palliation had similar median survival (94 vs. 92 days) but shorter hospitalization (4 vs. 14 days), which led to overall lower cost ($9,921 vs. $28,173).

ERCP IN THE SETTING OF CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

ERCP has evolved from a diagnostic to a therapeutic tool for patients with CP as a result of advances in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), computed tomography (CT), and EUS. Pancreatic ductal changes on ERCP can be classified by the Cambridge classification as equivocal (type I), mild to moderate (type II), and severe (type III). The classification has been shown to correlate with the severity of exocrine insufficiency. However, some patients with early CP have a normal pancreatogram. Achieving a definitive diagnosis in this population is challenging and requires the incorporation of other imaging and pancreatic function testing.

Pain from CP is probably multifactorial, although one suggested mechanism is pancreatic ductal hypertension due to pancreatic duct obstruction from a stricture or stone. Therapeutic ERCP can alleviate pain and recurrent pancreatitis flares with serial dilation of pancreatic duct strictures or stone extraction. Similar to the treatment of benign bile duct strictures, pancreatic duct strictures are managed with serial dilation and placement of one or more plastic stents until the stricture is obliterated. This usually requires three or more ERCPs occurring every 2 to 4 months for up to 1 year. Pancreatic stones are more easily removed if they are small, few in number, closer to the head of the pancreas, and not impacted. For either stricture or stone management, a pancreatic sphincterotomy is usually required. Stones upstream to the tail from a pancreatic duct stricture require stricture dilation before extraction. Other options for stone removal include direct pancreatoscopy, electrohydraulic lithotripsy, and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). Notably, ESWL alone may be as effective as ESWL combined with ERCP for therapy of pancreatic duct stones. Although studies have shown endoscopic therapy may improve pain, in CP, the short- and long-term efficacy of endoscopic treatment are inferior to surgical interventions aimed at relieving obstruction and achieving pain relief.

ERCP IN THE SETTING OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

The role of ERCP in the early management of patients with acute pancreatitis is limited. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis, urgent ERCP (to be performed within 72 hours of presentation) is indicated only in the setting of concomitant acute cholangitis or severe acute pancreatitis with biliary obstruction. The benefits of early ERCP remain controversial. One meta-analysis concluded early ERCP reduced complications but not mortality in severe biliary pancreatitis and had no benefit in mild pancreatitis. Two other meta-analyses found no benefit in morbidity or mortality from early ERCP in biliary pancreatitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree