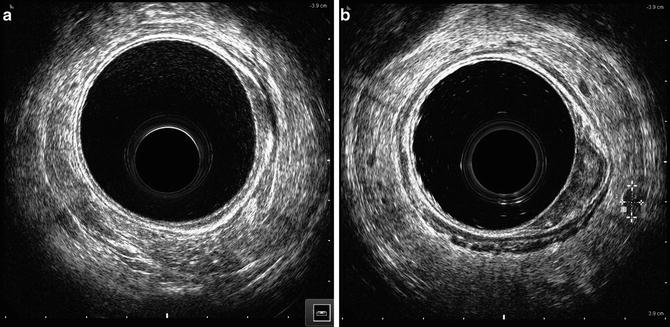

Fig. 2.1

Five-layer model of ERUS image (Beynon). Model image with ERUS layers seen on the left and corresponding layers of the rectal wall seen on the right

The accuracy of staging using the Beynon model as compared to the Hildebrant and Feifel model has minimally been studied; however, one study suggested that the Beynon model has greater accuracy [10]. At our institution, the Beynon model is favored, and generally, this is the model used by most practitioners today.

In addition to the layers of the rectal wall, ERUS can also be employed to visualize perirectal anatomy. Pelvic floor muscles and the sphincter complex can be seen on ERUS. Puborectalis can be seen using ERUS in the upper anal canal, whereas the internal anal sphincter (hypoechoic) is seen in the middle portion of the anal canal, and the external anal sphincter (hyperechoic) is seen in the lower anal canal [11]. Other structures that can be appreciated with ERUS in males include the seminal vesicles, the prostate, the bladder, and the urethra. In addition to perirectal fat and lymph nodes, loops of bowel may be appreciated. Retrorectal cystic masses can also be appreciated (Fig. 2.2).

Fig. 2.2

Retrorectal cystic mass

Endorectal Ultrasound for Staging in Rectal Cancer

Endorectal ultrasound can be used to preoperatively stage rectal tumors according to uTNM staging initially introduced in the 1980s [7]. uTNM staging is based upon depth of tumor invasion as well as evidence of nodal metastasis. Currently, the uTNM staging is as follows:

uT0

Lesion is confined to the mucosa.

uT1

Lesion confined to the mucosa and submucosa.

uT2

Lesion penetrates into but not through the muscularis propria.

uT3

Lesion penetrates bowel wall into the perirectal fat.

uT4

Lesion penetrates adjacent organs, pelvic sidewall, or sacrum.

uN0

No evidence of lymph node involvement.

uN1

Evidence of lymph node involvement.

T-Staging

uT0

Lesions classified as uT0 are considered noninvasive lesions or benign lesions. On ERUS, a uT0 lesion is confined to the mucosa and does not penetrate the submucosa. An irregular expansion of the hypoechoic layer that corresponds to the mucosa and muscularis interface will be seen, representing the tumor. However, the submucosa is completely intact (Fig. 2.3a). uT0 lesions can be treated with local excision therefore, any penetration invasion of the submucosa must be accurately excluded.

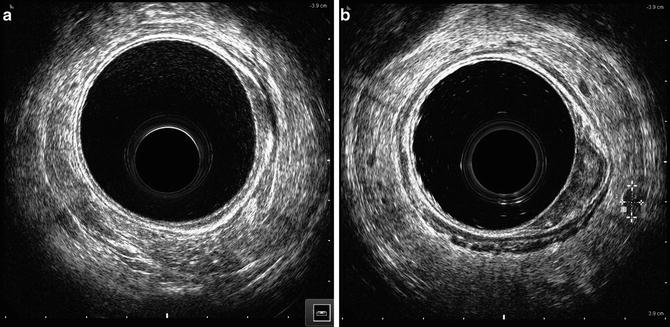

Fig. 2.3

T-stages based upon EUS. (a) uT0 , noninvasive lesions or benign lesions, adenoma (b) uT1 lesion with invasion of the submucosa, but not the muscularis propria (c) uT2 lesion with complete disruption of the second hyperechoic layer, corresponding penetration of the tumor through the submucosa with invasion of the muscularis propria. (d) uT3 tumor with penetration through the muscularis propria and into the perirectal fat

uT1

uT1 lesions on ERUS are lesions that have invaded the submucosa but not the muscularis propria. These lesions are considered early invasive rectal cancers. uT1 tumors will show an irregularity of the second hyperechoic layer, but no distinct break in this layer (Fig. 2.3b). This indicates incomplete disruption of the submucosa, but not penetration of the tumor through the submucosa into the muscularis propria.

uT1 lesions can be treated with local excision with curative intent; therefore, staging these tumors correctly is critical due to the increased risk of local recurrence with preoperative understaging [12–14]. Favorable characteristics for local excision include well or moderate differentiation on histopathology, no evidence of lymphovascular invasion, no perineural invasion, no mucinous components, tumor size <3 cm, tumor involving <1/3 the circumference of the rectal wall, tumor <10 cm from the anal verge, and mobile lesion [15].

uT2

Sonographically, uT2 lesions show a complete disruption of the second hyperechoic layer, corresponding penetration of the tumor through the submucosa with invasion of the muscularis propria (Fig. 2.3c). The key feature of a uT2 tumor is a distinct break of the second hyperechoic layer seen on ERUS.

uT3

Penetration of the tumor into the perirectal fat, through the muscularis propria is indicative of a uT3 tumor. On ERUS, the image will show a disruption of all layers of the rectal wall, with extension of the lesion into the perirectal fat (Fig. 2.3d). Patients with uT3 lesions are not candidates for local excision and will need preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy prior to radical surgery.

uT4

uT4 lesions are locally advanced lesions that invade perirectal structures such as the prostate, seminal vesicles, pelvic sidewall, bladder, uterus, cervix, or vagina. Sonographically, there is loss of the plane between the tumor and adjacent organ of interest. Most uT4 lesions are confirmed using MRI. Usually, patients with uT4 tumors will require preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy prior to an operation involving en bloc resection of the involved organs when feasible and indicated.

N-Staging

ERUS can also be used to visualize perirectal lymph nodes and provide information about their disease involvement. N-staging is important given the decreased survival and increased local recurrence associated with nodal involvement. ERUS N-staging is classified into uN0 and uN1. uN0 denotes undetectable or benign appearing lymph nodes, indicating no lymph node involvement (Fig. 2.4a). Generally, normal non-enlarged lymph nodes are not detected by ERUS. uN1 indicates involvement of perirectal lymph nodes (Fig. 2.4b).

Fig. 2.4

Lymph node assessment with EUS (a) uN0, (T2) with no evidence of lymph node metastasis (b) uN1, (T2) evidence of lymph node metastasis as indicated by dotted lines

The involvement of the lymph nodes is usually suspected if the lymph nodes are greater than 5 mm in diameter, rounded, and hypoechoic [16–18]. However, metastatic foci have been reported in nodes that are smaller than 5 mm at a rate of 18% [19, 20]. Although the incidence of metastatic disease increases as the size of the lymph node increases, a definitive size threshold does not exist to distinguish nonmalignant from malignant lymph nodes [21]. Involved lymph nodes are usually seen adjacent to the primary tumor or in the mesorectum near the primary tumor. Note that hypoechoic lesions seen perirectally have also been found to be tumor deposits and very small hypoechoic spots have also been shown to correlate with significant venous or lymphatic invasion on histologic evaluation [22].

Inflamed lymph nodes can be distinguished from malignant lymph nodes as they are generally enlarged but not as large as malignant lymph nodes, and they are often slightly hyperechoic [16]. Both can have irregular borders. When confronted with lymph nodes that are of mixed echogenicity that are larger than 5 mm, these should be considered malignant.

Accuracy of uTNM Preoperative Staging

The overall accuracy of staging of ERUS for rectal cancer varies between studies. A recent meta-analysis shows that the overall accuracy of T-staging ranges from 88 to 95% [23] depending upon the T-stage. Other meta-analyses cite accuracy of T-staging ranging from 76 to 96% [20, 24] and another ranging from 75 to 87% [25]. More recent data suggest that ERUS is most accurate for early tumors, especially T0 and T1 tumors [26, 27]. Approximately a quarter of rectal adenomas can be misdiagnosed on initial biopsy with a finding of invasive adenocarcinoma on final pathology; however, ERUS is able to detect up to 81% cases with focal carcinoma identified on final pathology [28]. ERUS is recommended for staging early tumors, with excellent sensitivity (97.3%) and specificity (96.3%) in diagnosing T0 tumors [26]. When looking at rectal cancer as early versus advanced stage, ERUS also has high specificity and accuracy for staging advanced tumors, 96% and 94%, respectively [12]. ERUS is currently the most accurate modality for evaluating T1 rectal tumors [27], whereas it is least accurate for staging T2 tumors, often due to overstaging [29–31]. The accuracy of uT3 based upon meta-analyses is thought to be 88–96% [20, 24, 25, 29].

The accuracy of nodal metastasis assessment with ERUS is less than the accuracy for T-staging [32–34], with a mean accuracy for T-stage of 85% and a mean accuracy for N-stage of 75% in one study [35]. Its accuracy in excluding lymph node involvement may be better than confirming it [34]. With regard to the accuracy of ERUS for N-staging, it is thought that earlier tumors have smaller metastatic deposits, and therefore positive nodes are more likely to be missed by ERUS . In one study, the ability to correctly stage lymph node status drops from 84% in T3 tumors to 48% for T1 tumors [36]; this was attributed to a drop in the median size of the lymph nodes and metastatic deposits from 8 mm to 3.3 mm and 5.9 mm to 0.3 mm, respectively, when going from T3 to T1 tumors.

It has been proposed that ERUS be combined with a technique for obtaining specimens for further analysis when it is used to guide a needle biopsy or needle aspirate, allowing for further use in the evaluation of rectal cancer. This approach can provide diagnostic material for ancillary studies as well as allow the evaluation of perirectal lesions in a more accurate manner by combining both imaging and histology [37]. The use of this technology may help increase the specificity of nodal staging with ERUS; however, further studies are still needed to validate the role of ERUS with guided biopsy/FNA.

Other imaging modalities have been employed for preoperative staging, including CT scan, PET scan, and MRI. CT scans are considered the standard of care for detecting widely metastatic disease. Its role, however, in local staging is minimal as it is unable to delineate the layers of the rectal wall. In a study comparing the accuracy for spiral CT and ERUS for T-staging , the results show 70.5% and 84.6%, respectively. With nodal staging, there seemed to be no difference in CT as compared to ERUS for evaluating nodal metastasis, with a reported accuracy of 61.5% and 64.1%, respectively [38]. Much like with CT scans, the lack of detailed anatomy provided by PET CT scans make local T-staging and lymph node involvement difficult to ascertain [39, 40].

Unlike ERUS, MRI does not provide excellent visualization of the layers of the rectal wall, which is key in local staging. It is thought that ERUS provides better visualization of superficial tumors or early stage, whereas MRI allows better assessment of locally advanced or stenotic tumors [25, 41]. When evaluating nodal metastasis, MRI and ERUS show similar results for muscularis propria invasion, but MRI has higher sensitivity for perirectal tissue invasion [42]. The overall sensitivity and specificity of MRI to assess lymph node involvement was 77% and 71%, respectively [43]. These data suggest that there may be a complimentary role for ERUS and MRI in the evaluation of lymph nodes [41]. Where MRI is thought to be clearly better than ERUS is for visualizing the circumferential resection margin after resection [44].

Currently, ERUS is routinely a first-line modality for imaging and local staging of rectal cancers and with good supporting data as reviewed in this chapter. Its adjunct is CT scan for distant metastasis. The use of multiple modalities for preoperative staging will give the most accurate results , especially if the images obtained by ERUS are not straight forward such as in the case of highly stenotic and locally advanced tumors.

Limitations of Endorectal Ultrasound

Evaluation of response to chemoradiation therapy (CRT) or restaging after CRT with ERUS is limited by the inflammation, necrosis, fibrosis, and post-radiation edema. Therefore, ERUS has a limited role in this arena with reported accuracies of 46–47% [45, 46]. The misinterpretation rate was found to be highest in responsive patients where accuracy rates were the lowest (29%) [47]. There are authors who feel that when there is residual tumor present, it is limited to the area of fibrosis, allowing for determination of the maximum possible determination of depth of invasion [48, 49]. However, further studies are needed to identify and confirm post-CRT sonographic changes, and better rates must be reported before ERUS is recommended for restaging post-CRT.

Operator dependence is also thought to be a limitation of ERUS. The learning curve for T-staging and N-staging are reported to be approximately 50 and 75 cases, respectively [18]. Accuracy is thought to vary with the level of experience of the operator [33, 50], allowing for some of the variations seen among different studies with regard to accuracy of ERUS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree