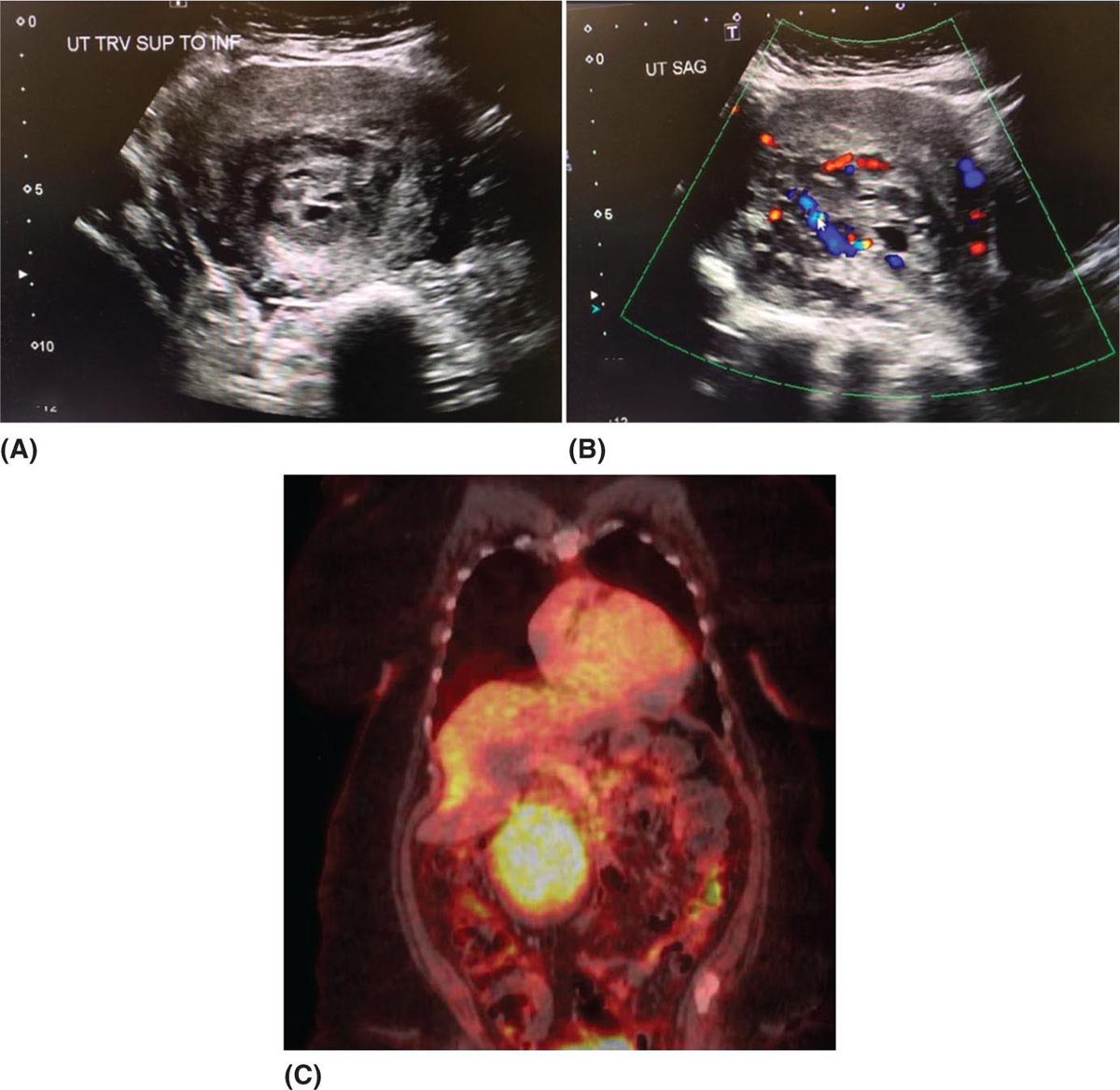

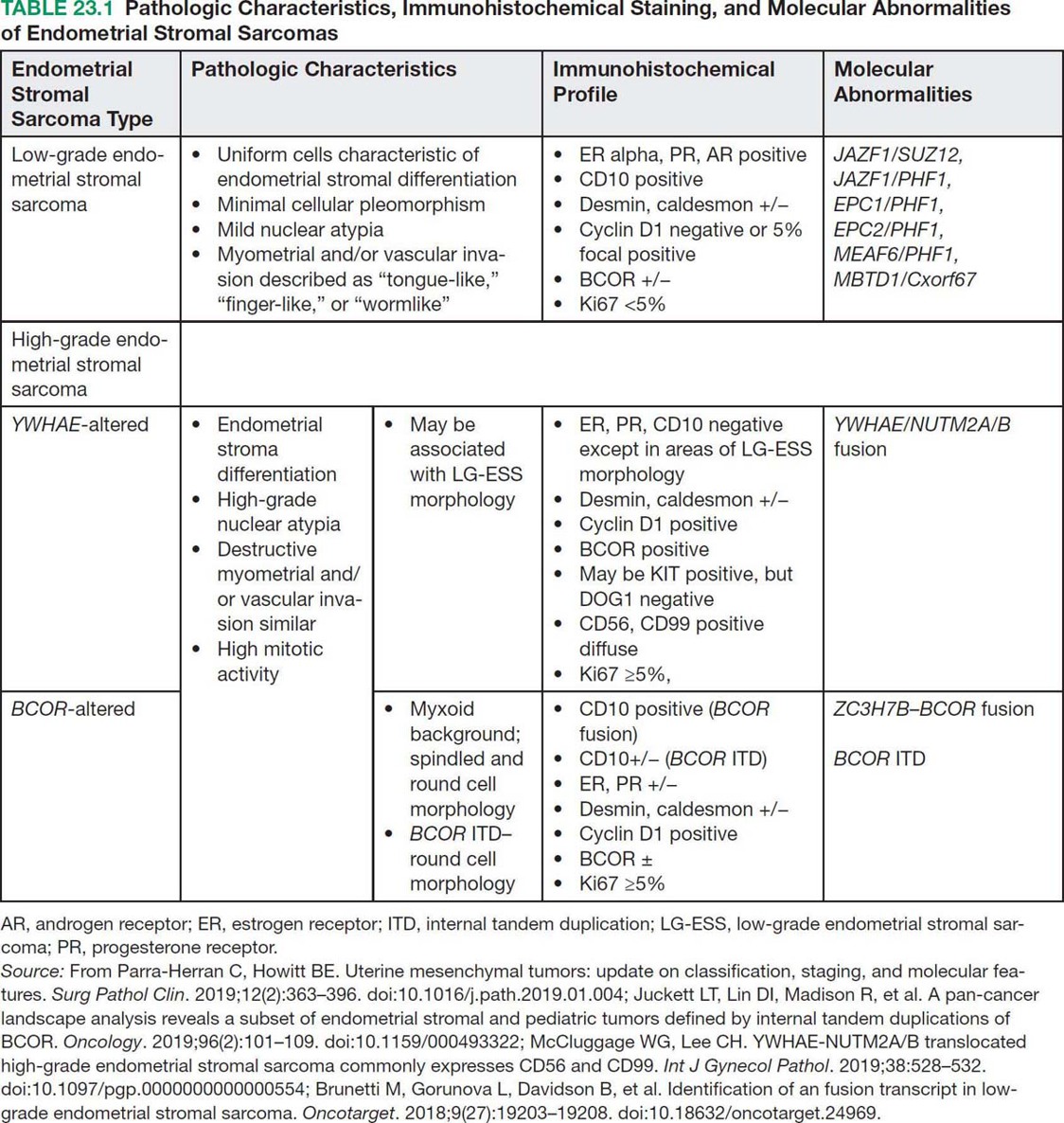

29923 Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) represents a very rare subset of uterine mesenchymal neoplasms and endometrial stromal tumors. Endometrial stromal tumors are grouped according to the World Health Organization 2014 classification system into four distinct categories: endometrial stromal nodules, low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS), high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS), and undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUS). This chapter focuses on LG-ESS and HG-ESS subtypes, which are defined by divergent morphologic appearance, molecular aberrations with distinctive gene translocations, therapeutic management, and prognosis. LG-ESSs are malignant tumors composed of nonneoplastic endometrial stromal cells with myometrial and vascular “tongue-like” infiltration patterns. LG-ESSs tend to have a more indolent course and are treated with hormonal therapies. HG-ESSs have high-grade nuclear atypia and mitotic activity with a more destructive infiltrative pattern of myometrial and lymphovascular invasion. HG-ESSs are associated with a more aggressive clinical behavior and worse survival outcomes. This chapter discusses distinctive clinicopathologic features, underlying molecular biology, management, and survival outcomes for LG-ESSs and HG-ESSs. Endometrial stromal sarcoma, Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma endometrial stromal nodules, endometrial stromal sarcoma, high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, prognosis, therapeutic management, undifferentiated uterine sarcoma, World Health Organization Prognosis, Sarcoma, Endometrial Stromal, Therapeutics, World Health Organization INTRODUCTION Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) represents a very rare subset of uterine mesenchymal neoplasms and endometrial stromal tumors. Overall, ESSs represent 0.2% to 1% of all uterine malignant neoplasms and account for approximately 10% to 20% of uterine sarcomas.1–3 Endometrial stromal tumors are grouped according to World Health Organization (WHO) 2014 classification system into four distinct categories: (a) endometrial stromal nodules, (b) low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (LG-ESS), (c) high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (HG-ESS), and (d) undifferentiated uterine sarcoma (UUS).1 The focus of this chapter is on the ESS comprising LG-ESS and HG-ESS. LG-ESS and HG-ESS subtypes are defined by divergent morphologic appearance, molecular aberrations with distinctive gene translocations, therapeutic management, and prognosis. LG-ESS are malignant tumors composed of nonneoplastic endometrial stromal cells with myometrial and vascular “tongue-like” infiltration patterns. The sarcomas typically have uniform cells, characteristic of endometrial stromal differentiation with minimal cellular pleomorphism and mild nuclear atypia. Common molecular alterations include the rearrangements of the JAZF1 and PHF1 genes. LG-ESSs tend to have a more indolent course and are treated with hormonal therapies. In comparison, HG-ESSs have high-grade nuclear atypia and mitotic activity with a more destructive infiltrative pattern of myometrial and lymphovascular invasion. HG-ESSs are more likely to demonstrate tumor cell necrosis. They are characterized by YWHAE/FAM22 translocations and BCL6 corepressor (BCOR) alterations. HG-ESSs are associated with a more aggressive clinical behavior and worse survival outcomes.1 This chapter will focus on LG-ESS and HG-ESS and review distinctive clinicopathologic features, underlying molecular biology, management, and survival outcomes. TERMINOLOGY OF ENDOMETRIAL STROMAL NEOPLASMS Historically, the nomenclature for endometrial stromal tumors has been confusing because of the use of numerous diagnostic terms including stromal adenomyosis, stromatosis, endolymphatic stromal myosis, and stromal sarcoma. In 1966, Norris and Taylor, described a new classification system for endometrial stromal tumors based on clinicopathologic features of 53 tumors. The authors classified tumors using two groups based on the type of margin. The tumors with pushing margins were denoted as stromal nodules and were considered benign. The other main type of tumor was characterized by infiltrating margins and was referred to as either endolymphatic stromal myosis (low-grade) or stromal sarcoma (high-grade) based on mitotic activity. Endolymphatic stromal myosis had less than 10 mitotic figures in 10 high-power fields (HPFs) and had a clinically indolent course with an excellent prognosis of 100% 5-year survival. In contrast, stromal sarcomas were characterized by greater than 10 mitotic figures in 10 HPFs and had a more aggressive phenotype with worse survival.4 The arbitrary division of ESS into low-grade and high-grade based on mitotic count was later abandoned, as mitotic activity was deemed irrelevant with regard to prognosis.5 In 2003, WHO proposed a two-type classification system: (a) ESS that included low-grade tumors characterized by proliferative endometrial stroma and (b) undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma, which consisted of pleomorphic tumors that did not resemble endometrial stromal cells.5 However, the undifferentiated endometrial sarcomas included a heterogeneous subset of tumors with a different clinical phenotype, a novel gene rearrangement, and survival outcomes intermediate between the low-grade ESS and undifferentiated 300sarcomas.5 The recognition of this distinct cohort of tumors led to the second WHO iteration of endometrial stromal neoplasm classification and inclusion of HG-ESS into the terminology. The 2014 WHO classification for endometrial stromal neoplasms incorporated molecular findings into the classification system and includes four specific categories: (a) endometrial stromal nodule (which is a benign tumor), (b) LG-ESS, (c) HG-ESS, and (d) UUS.1 The evolving terminology and classification for endometrial stromal neoplasms can lead to difficulty reviewing and interpreting the literature. For instance, older literature of uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumor may include cases now classified as LG-ESS; tumors previously categorized as undifferentiated endometrial or high-grade undifferentiated uterine sarcomas are now classified as HG-ESS; and the term undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma is no longer used.6 The focus of this chapter will review the two invasive endometrial stromal neoplasms, referred to as LG-ESS and HG-ESS. The pathologic, molecular characteristics, therapeutic recommendations, and surveillance are based on the 2014 WHO classification system. Aligning classification appropriately to the current terminology is challenging and reference may be made to literature using older terminology. ESTIMATED INCIDENCE PER YEAR AND EPIDEMIOLOGY Overall, ESSs represent 0.2% to 1% of all uterine malignant neoplasms and account for approximately 10% to 20% of uterine sarcomas.1–3 Patients typically present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, postmenopausal bleeding, enlarged uterus or uterine mass, dysmenorrhea, pelvic pressure, or pain.2,6 These tumors may also be asymptomatic in as many of 25%, or may be mistakenly diagnosed as leiomyoma.3 Endometrial sarcomas are often not suspected and commonly are diagnosed following hysterectomy or myomectomy. LG-ESS is more common than HG-ESS. LG-ESS typically develops in women between 40 and 55 years of age, >50% occur in premenopausal women, and they have been reported in young women or adolescents.1,3 LG-ESS has been associated with prolonged estrogen exposure, tamoxifen use, and pelvic radiation.1 LG-ESSs typically are indolent tumors characterized by excellent prognosis. Overall, the survival rates are 65% to 76% at 10 years.6,7 However, the 5-year survival estimates for women with stage I and II disease are excellent and greater than 90%. In comparison, those with advanced disease have a higher incidence of recurrent disease and 5-year survival outcomes ranging from 40% to 50%.1 Approximately 30% of patients will have extrauterine disease at presentation (most commonly to the ovary). Recurrence rates range from 30% to 56%, late recurrences being common, and 15% to 25% of patients succumb to recurrent disease.3,7,8 HG-ESSs occur at a mean age of 50 years (range 28–67 years) and often are symptomatic with abnormal vaginal bleeding, an enlarged uterus, or a pelvic mass.3 HG-ESS has worse survival rates compared to LG-ESS and typically presents with advanced stage disease.1 Patients with HG-ESS are more likely to develop recurrent disease within an earlier time frame.3 The median overall survival ranges from 11 to 23 months.9 HG-ESS has a favorable prognosis compared to undifferentiated uterine sarcomas. DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH When patients present with abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding and uterine mass, the evaluation should comprise a complete history, physical examination including pelvic exam, endometrial biopsy, and pelvic imaging. The differential diagnosis is extensive and includes leiomyoma, endometrial stromal nodules, endometrial stromal sarcoma subtypes, leiomyosarcoma; solitary fibrous tumors or hemangiopericytoma, undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas, uterine tumor resembling ovarian sex cord tumors, and undifferentiated uterine sarcomas.1 Pelvic examination cannot differentiate between a benign uterine mass, such as leiomyoma, and uterine sarcoma. Diagnostic approaches, such as endometrial sampling via biopsy or curettage can be performed. However, the accuracy of endometrial samples for ESS is uncertain owing to the rare frequency of this disease. In a report of 938 patients, only two had stromal sarcomas and both were identified on preoperative endometrial sampling.10 Other modes of biopsy, either transcervical or transperitoneal, have been considered. Transcervical biopsy limits the risk of peritoneal spread, but may not reach all masses.11 Imaging features of endometrial sarcomas can be distinct from leiomyoma, but diagnosis requires heightened suspicion as discussed in the next section, “Radiographic Features and Recommended Imaging.” 301If the diagnosis is made preoperatively, a complete blood count and chemistry panel to assess liver and renal function as well as chemistry profile should be considered.12 However, often the diagnosis is made postoperatively after hysterectomy or myomectomy for presumed benign disease. If diagnosed postoperatively, obtain expert pathologic review, request estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR) testing, and perform imaging to assess for metastatic and unresected disease.12 RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES AND RECOMMENDED IMAGING Radiologic imaging typically includes pelvic ultrasound and pelvic MRI. On ultrasound exam, ESS has a nonspecific pattern or appearance of a heterogeneous hypoechoic endometrial mass (Figure 23.1A), with myometrial involvement. On Doppler ultrasound, low-resistance intralesional arteries and increased vasculature, which can be central or peripheral, are seen (Figure 23.1B). Key diagnostic findings of low-flow resistance within the intralesional arteries and the structural findings should increase suspicion for malignancy.2 On MRI, these neoplasms may appear as large polypoid masses that expand the endometrial cavity. The masses can be diffusely infiltrative and have irregular margins, and are characterized by multiple nodular lesions or masses and intramyometrial nodule extensions. A key feature characterized by a low-intensity rim on T2-weighted images may indicate hemorrhage and raise index of suspicion for ESS. Another important characteristic of ESS are the “worm-like” invasive projections that can be seen along the vasculature and ligaments on diffusion-weighted imaging.2 MRI is useful to evaluate for locally metastatic tumor, pelvic extension of disease, and residual disease in cases of incomplete resection, intraperitoneal morcellation, or tumor fragmentation.12 Examples of incomplete resection include supracervical hysterectomy and myomectomy. FIGURE 23.1 Radiologic imaging of endometrial stromal sarcomas. Nonspecific pattern or appearance of a heterogeneous hypoechoic endometrial mass on ultrasound (A) with low-resistance increased peripheral vasculature (B). Metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma involving para-aortic node with high maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) (C). 302CT scans can be useful to assess for metastatic disease. PET with or without CT can be utilized to clarify ambiguous findings.12 There are limited data regarding PET in ESS; often the studies group the various sarcomas. PET may be useful to distinguish between uterine sarcomas and leiomyoma (Figure 23.1C). A small study including 15 uterine sarcomas and 19 leiomyomas demonstrated that the median maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) for these tumors was significantly different. Uterine sarcomas have higher median SUVmax of 12 compared to leiomyoma with a median SUVmax of 4.1.13 PET imaging with a novel tracer, [18F]-fluoroestradiol (FES) labeling, has been reported in patients receiving hormonal therapy demonstrating a correlation between decreased FES uptake on imaging and disease response.14 PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS OF ENDOMETRIAL STROMAL SARCOMAS The anatomic location of ESS is similar for both low- and high-grade types. ESSs are intrauterine tumors and have propensity to invade the myometrium and vasculature. Distinguishing between endometrial stromal nodules, LG-ESS, HG-ESS, and other types of sarcomas can be challenging. Therefore, expert pathologic review is strongly recommended. Immunohistochemistry to assess protein and receptor expression as well as molecular characterization of the tumors for diagnostic purposes is helpful. These additional tests can be utilized to distinguish endometrial sarcomas from other mesenchymal neoplasms as well as LG-ESS from HG-ESS. While endometrial stromal nodule is not the focus of this chapter, discussing the pathologic features of this neoplasm is important in order to distinguish from LG-ESS. Endometrial stromal nodules are benign tumors. The majority of endometrial stromal nodules are isolated yellow myometrial masses without endometrial involvement. They are typically well defined and circumscribe with a softer consistency compared to leiomyoma.15 Histologically, endometrial stromal nodules have similar features as compared to LG-ESS and are characterized by proliferative endometrium appearance. Moreover, immunostaining and molecular abnormalities are similar in both endometrial stromal nodules and LG-ESS. In contrast to LG-ESS, endometrial stromal nodules do not display lymphovascular invasion, and the absence of invasion is the diagnostic hallmark to distinguish between LG-ESS and endometrial stromal nodules.15 Pathologic Characteristics of LG-ESS LG-ESSs are low-grade sarcomas characterized by uniform cells characteristic of endometrial stromal differentiation with minimal cellular pleomorphism and mild nuclear atypia (Table 23.1). Mitotic figures may be present but do not appear to confer a worse prognosis. LG-ESSs also demonstrate myometrial and/or vascular invasion.15 Grossly they are often recognized at the time of hysterectomy specimen evaluation by the characteristic “tongue-like” or “finger-like” pattern of myometrial invasion and involvement of the vasculature. As noted above, they have similar histologic features of endometrial stromal nodules. The differential diagnosis may include endometrial stromal nodule, intravascular leiomyomatosis, leiomyosarcoma, uterine tumors with ovarian sex cord-like features, fibromyxosarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Diagnosis can be challenging owing to the presence of various histologic findings, including collagen bands, smooth muscle, skeletal muscle, cholesterol clefts, histiocytes, sex cord, glandular components, fibromyxoid, and rhabdoid features.1,6,15 Smooth muscle differentiation is present in approximately 45% of cases and about 25% exhibit sex cord-like differentiation. LG-ESS may also mimic fibromyxosarcoma, solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor with spindled tumor cells appearing fibroblastic or myofibroblastic-like. Even more challenging, metastatic LG-ESS may appear different from the primary tumor.1 The “tongue-like” invasive pattern helps distinguish LG-ESS from leiomyosarcomas that have a more destructive infiltrative pattern.6,15 LG-ESSs commonly express estrogen receptors (ERs) alpha, progesterone receptors (PRs) and androgen receptors (ARs). These tumors are often strongly positive for CD10 (75%–90%), usually exhibit positive staining for smooth-muscle actin and WT-1, less commonly for desmin (30%) and nuclear beta-catenin expression (40%). LG-ESSs are negative for h-caldesmon and HDAC8. Ki67 is less than 5%.3,15,16 Pathologic Characteristics of HG-ESS HG-ESSs are malignant neoplasms notable for endometrial stroma differentiation and characterized by high-grade nuclear atypia.1,15 The nuclei are larger, more angulated, and irregular compared 303to those in LG-ESS.1 These tumors may also demonstrate the “finger-like” invasive pattern into the myometrium analogous to LG-ESS, but demonstrate more extensive and destructive invasion. Mitotic activity is common and consistently >10 per 10 HPFs. HG-ESSs more commonly demonstrate tumor cell necrosis. The histologic variations seen in LG-ESS, such as glandular and sex cord-like patterns, are rarely present.1,6 The morphology of HG-ESS varies based on the molecular subtype (Table 23.1). HG-ESS are subclassified based on molecular alterations and the different subtypes may have distinguishing morphology: (a) YWHAE-NUTMN2 altered HG-ESS and (b) BCL6 corepressor (BCOR) altered HG-ESS.15 The BCOR altered tumors represent a second form of HG-ESS and may be due to either ZC3H7B-BCOR gene fusions or BCOR internal tandem duplication (ITD).17 The YWHAE-NUTMN2 HG-ESSs have uniform epithelial cells arranged in nests associated by a delicate and branching vasculature. They are associated with typical LG-ESS morphologic appearance. The nuclei may exhibit increased pleomorphism and mitoses are present, but bizarre atypia should not be present. In contrast, the BCOR altered tumors have a different microscopic appearance, characterized by spindle cells and a prominent myxoid stroma. ZC3H7B-BCOR associated HG-ESS is characteristic of a new subset of myxoid HG-ESSs, which share morphologic overlap with myxoid LMS.18 The BCOR ITD sarcomas often have a round cell component.19 304HG-ESS are typically negative or have limited ER alpha, PR, and AR expression. HG-ESSs exhibit strong and diffuse cyclin D1 immunostaining.16 HG-ESSs have been reported to staining positively for c-KIT, but negative for DOG1.3 The two HG-ESS subtypes have different staining patterns (Table 23.1). For example, the YWHAE-NUTMN2 HG-ESS may exhibit CD10, ER, and PR staining in the low-grade component. In contrast, CD10, ER, and PR staining is absent or only focally positive in the high-grade component of these tumors. YWHAE-NUTMN2 HG-ESSs are strongly positive cyclin D1 in the high-grade areas, c-KIT negative, and demonstrate Ki67 ≥5%. Positive diffuse staining for CD56 and CD99 has also been reported.20 BCOR altered tumors may be due to either ZC3H7B/BCOR fusion or BCOR ITD. BCOR altered HG-ESS exhibit strongly positive cyclin D1 staining and higher Ki67 ≥5%. They may have limited ER/PR positivity. BCOR fusion HG-ESSs are strongly positive for CD10, while BCOR internal tandem duplication exhibit either focal/patchy CD10 positivity or are CD10 negative. Both YWHAE-NUTMN2 and BCOR altered HG-ESSs demonstrate BCOR expression.5,15 MOLECULAR ABERRATIONS OF ENDOMETRIAL STROMAL SARCOMAS Molecular genomic characterization in ESS can be very helpful to distinguish between low- and high-grade disease. Gene rearrangements, such as translocations, are common in both types of endometrial sarcomas.15 However, the types of translocation, generation of fusion proteins, and oncologic potential of the aberration varies in LG-ESS compared to HG-ESS. The research continues to evolve, with several new translocations reported recently. Molecular Aberrations of LG-ESS LG-ESS have molecular features characterized by gene translocations. There are several of these translocations resulting in gene fusions, and most commonly the JAZF1 gene is involved.15 Translocations frequently involve chromosomes 6p, 7p, and 17q. One such translocation, t(7;17), JAZF1/SUZ12 (formerly JAZF1/JJAZ1) is present in up to 50% of LG-ESS. The translocation is the result of the fusion of two zinc finger genes, JAZF1 and SUZ12 (formerly JJAZ1), and creation of the JAZF1/SUZ12 fusion protein.1,15 While commonly seen in LG-ESS, this translocation has not been found in other uterine sarcomas or smooth-muscle neoplasms. Other translocations and gene fusion proteins have been identified in LG-ESS and often involve the PHF1 gene. These rearrangements include t(6;7), t(6;10), t(2;6), t(1;6), t(5;6) and their resulting fusion gene products: JAZF1/PHF1, EPC1/PHF1, EPC2/PHF1, MEAF6/PHF1, BRD8/PHF1, respectively.15,21 When translocations are present, the type and frequency are as follows: JAZF1/SUZ12 (80%); JAZF1/PHF1 (6%), EPC1/PHF1 (4%), MEAF6/PHF1 (3%), MBTD1/Cxorf67 (2%).15 Molecular Aberrations of HG-ESS HG-ESS are characterized by molecular aberrations, and it was the discovery of the YWHAE-NUTM2 fusion genes (formerly known as YWHAE/FAM22A/B) gene rearrangement that helped redefine the HG-ESS category in the WHO 2014 classification system.1 HG-ESSs are subclassified by type of molecular alterations: the YWHAE-altered HG-ESS and BCOR-altered HG-ESS. BCOR-altered HG-ESS comprise tumors that have either ZC3H7B-BCOR gene fusions or BCOR ITD.15,17,19 YWHAE-NUTM2 fusion genes represent a common t(10;17) translocation.15 Molecular testing to identify fusion transcripts may be very helpful to distinguishing between LG-ESS, HG-ESS, and other types of mesenchymal neoplasms as well as assist in the diagnosis of the ESS subtypes, YWHAE-NUTM2 and BCOR altered tumors. BCOR-associated ESSs have been classified as low-grade as well as high-grade ESS tumors.22 The clinical relevance of the molecular alterations is not fully understood. Given the literature reports regarding a more aggressive clinical course, the BCOR-associated ESS will be considered in the HG-ESS category. Other novel gene rearrangements, for example, EPC1-SUZ12, EPC1-BCOR, and NTRK fusions, have been reported.17,23 STAGING FOR ENDOMETRIAL STROMAL SARCOMAS Historically uterine sarcomas were staged using a staging system proposed for endometrial cancers in 1988. In 2009, a new International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system was developed specifically for uterine sarcomas. This new staging system had two divisions, one for ESS and leiomyosarcoma, and the other one for adenosarcoma.3 Currently, staging for ESS utilizes the 3052017 Tumor, Node, Metastasis (TNM) staging system of the combined American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) and the FIGO staging system (Table 23.2). Importantly, ESS are not surgically staged and lymphadenectomy does not have therapeutic value and is not routinely recommended for staging purposes.3,8,11 TABLE 23.2 Staging of Uterine Sarcomas: Leiomyosarcomas and Endometrial Stromal Sarcomas

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

Stéphanie Gaillard and Angeles Alvarez Secord