Pituitary Adenoma Subtypes

PRL-secreting Adenomas (Lactotroph Adenomas). Prolactinomas are the most common PA in childhood, representing at least 50% of cases, and they are diagnosed most commonly in postpubertal girls. Prepubertal children present with symptoms of mass effect and/or delayed puberty, whereas pubertal children can also present with oligo- or amenorrhea (girls), galactorrhea (both genders), and rarely gynecomastia (boys).

12,13 Males are more likely to have macroadenomas and therefore tend to present with symptoms related to tumor size.

2,12The degree of hyperprolactinemia typically correlates with tumor size, and the diagnosis of a prolactinoma is highly likely when the PRL level is >250 ng/mL.

14 In cases where the PRL level and clinical findings are discordant, the differential diagnosis includes hyperprolactinemia due to stalk compression, the presence of macroprolactinemia, and assay artifact secondary to the high-dose hook effect that can occur with macroprolactinomas and extremely elevated PRL levels.

14 Patients with elevated PRL levels and no tumor on MRI should have an evaluation for secondary hyperprolactinemia. Primary hypothyroidism should always be ruled out as a cause of hyperprolactinemia and sellar mass. Because of the possibility of GH cosecretion, especially with tumor-predisposing genetic syndromes (

Table 36.1), an insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) level should also be included in the initial evaluation.

Prolactinomas can effectively be treated with one of the available dopamine agonists (DAs), either bromocriptine or cabergoline, even in the presence of visual changes. Cabergoline is preferred due to its less-frequent administration, fewer side effects, and greater efficacy.

14 Oral contraceptive pills are a reasonable alternative in adolescent girls with microadenomas and nonbothersome galactorrhea.

15,16 Sex steroids can exacerbate PRL hypersecretion and promote tumor growth, so caution should be undertaken when prescribing testosterone or estrogen replacement to adolescents with macroprolactinomas. The addition of an aromatase inhibitor may facilitate the use of testosterone replacement in males.

16Clinical improvement is usually seen before radiologic tumor reduction. In most patients, treatment is continued until the PRL level normalizes (or at least stabilizes) and the tumor demonstrates significant shrinkage. Some patients will never achieve normal PRL levels, but many patients may ultimately be able to stop DA therapy.

15,17ACTH-secreting Adenomas (Corticotroph Adenoma; CD). ACTH-secreting adenomas causing CD are the second most common PA in children, occurring in approximately one-third of children operated on for a pituitary tumor.

2,3 Corticotroph tumors are the most likely PA to be diagnosed in prepubertal children, and there is a female-to-male predominance, except in prepubertal children.

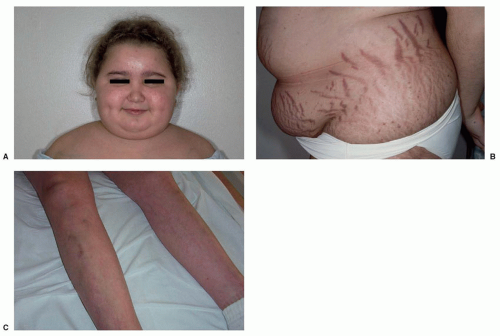

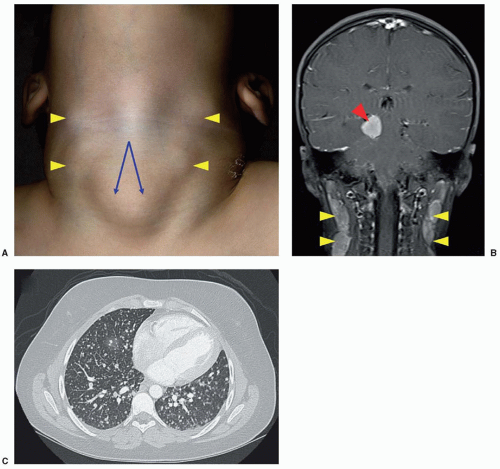

18,19The onset of symptoms is usually insidious, and most children have a typical Cushingoid phenotype (

Fig. 36.2) with generalized weight gain, obesity, impairment of growth (in prepubertal patients), violaceous striae (chiefly in older children), hirsutism/premature pubarche, acne, and hypertension.

18,20,21,22 Clinical presentation can also include rounding of the face (moon facies), plethora, abnormal fat distribution with increased fat deposition in the supraclavicular fossae and upper back (Buffalo hump), acanthosis nigricans, easy bruising, hyperpigmentation (with significant ACTH elevation), muscle weakness, edema, impaired glucose tolerance/diabetes mellitus, pubertal delay, emotional lability, fatigue, headache, menstrual disturbance, and low bone mass for age and fractures. Not every case of Cushing syndrome (CS) is classic, and the diagnosis can be hard to differentiate from exogenous obesity based on phenotype alone, as not all children with CS are short or have delayed bone ages as would be expected.

18,20 One of the most sensitive indicators of possible CS in a growing child is weight gain associated with a low growth velocity.

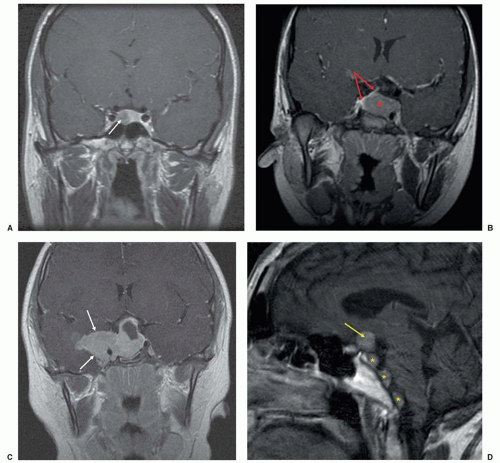

23These tumors are usually microadenomas and are often not visualized on routine MRI.

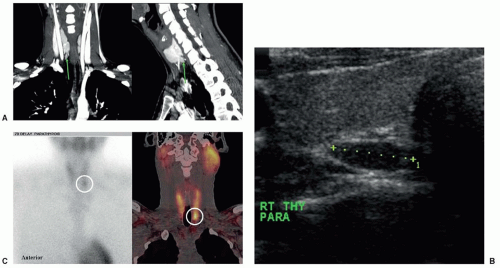

18,21 Because of that, the diagnosis of CD is not always straightforward and care must be taken to differentiate an ACTH-secreting PA from ectopic ACTH secretion, such as from a thymic or bronchial neuroendocrine tumor (NET).

24 Fortunately the latter situation is rare in children.

The diagnostic studies for CS have not been extensively validated in children. Screening studies to make the diagnosis include measurement of 24-hour urine-free cortisol, the overnight 1 mg (low dose) dexamethasone (DEX) suppression test, the 2-day low-dose DEX suppression test, and assessment of impaired circadian rhythm through the measurement of late evening salivary or serum cortisol levels.

18,23,25 The DEX/CRH test is utilized to distinguish CS from pseudo-CS states, although this test may not be as reliable in very obese children.

26 Once the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent CS (i.e., ACTH levels not suppressed and generally >15 pg/mL) has been made, the source of ACTH can generally be attributed to the pituitary if a clear adenoma is identified. If MRI findings are negative or equivocal, it is necessary to undertake additional testing to differentiate a pituitary from a peripheral source of ACTH production. These tests can include an overnight 8-mg (high-dose) DEX suppression test, 2-day high-dose DEX suppression test, CRH test, CRH/desmopressin test, and CRH-stimulated inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS).

18,23 IPSS obtained at the time of hypercortisolism appears to be the most definitive diagnostic test in the workup of ACTH-dependent CS and is safe and useful in children at experienced centers. Although IPSS can confirm a central source of ACTH production, its use solely for tumor lateralization is questionable.

The medical management of CD includes the use of inhibitors of cortisol synthesis (etomidate, ketoconazole, metyrapone, mitotane [o, p′-DDD; rarely used in nonmalignant conditions]) or action (mifepristone) as well as agents that can directly inhibit tumoral production of ACTH (cabergoline, pasireotide).

27,28 In the patient with CD who is not cured with surgery or radiotherapy and who continues to suffer from CS despite optimization of medical therapy, bilateral adrenalectomy is favored. Although patients are committed to life-long glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement, removal of all adrenocortical tissue is the best way to cure CS in the treatment-refractory patient. The development of Nelson syndrome (the association of an expanding pituitary tumor and a high ACTH concentration after adrenalectomy in patients with CD) is a theoretical concern in such children.

29GH-Secreting Adenomas (Somatotroph Adenomas; Gigantism/Acromegaly). Somatotroph adenomas are the third most common PA in childhood, have a higher prevalence in males, are usually macroadenomas, and represent about 8% of all cases and 0.63% of surgically treated pituitary tumors in children.

3,30 Gigantism is the term used to describe the overgrowth that occurs because of GH excess in children with open epiphyses, whereas acromegaly describes GH excess occurring after epiphyseal closure. The clinical presentation is usually one of accelerating linear growth. Other common features include coarse facial features, frontal bossing, prognathism, and disproportionately large hands and feet with thick fingers and toes. Symptoms related to tumor mass effect, pubertal delay, and menstrual irregularities can also be present at diagnosis.

30 Other signs and symptoms of GH excess that are more common in the patient with acromegaly are reviewed elsewhere.

31During early childhood, gigantism is typically caused by mammosomatotroph tumors, secreting both GH and PRL, underscoring the genetic basis of these tumors

9 (

Table 36.1). Sporadic adenomas can harbor somatic GNAS mutations in up to 40% of adult patients, but this is not generally seen in sporadic tumors identified in childhood.

32The best initial diagnostic test is measurement of an IGF-1 level, comparing it to age-matched normative ranges.

33 Confirmatory testing is accomplished through a 1.75 g/kg (max 75 g) oral glucose tolerance test, during which GH levels should fall to <1 ng/mL (<0.4 ng/mL in sensitive assays) during the 2-hour testing period.

33 The clinician must also consider the gender and pubertal status of the adolescent patient undergoing testing, as the nadir of GH after oral glucose ingestion may be higher than adults, especially in mid-pubertal girls.

34When surgery is not curative, pharmacologic inhibition of GH secretion and suppression of tumor growth are accomplished through the use of the somatostatin (SST) analogs (octreotide

and lanreotide) and/or the DA cabergoline.

31,35 Pegvisomant, a competitive GH receptor antagonist that lowers IGF-1 levels but has no direct impact on tumor size, is another treatment alternative. Primary medical therapy can be considered in patients who have surgically incurable tumors that are not compromising vision and in patients who are not good candidates for or refuse surgery.

Clinically Nonfunctioning Adenomas (Null Cell Adenomas; Gonadotropin-secreting Adenomas). Clinically nonfunctioning tumors include those neoplasms that silently produce hormones (e.g., ACTH) without clinical signs or symptoms, in addition to those PAs that produce no pituitary hormones (null cell adenomas), bioinactive hormones, or hormones such as the gonadotropins (luteinizing and/or follicle-stimulating hormone) and α-subunit of the glycoprotein hormones that do not always cause clinical manifestations.

9 In contradistinction to adults, these tumors represent <5% of pediatric PAs.

2,3 Surgery is the mainstay of treatment, particularly in macroadenomas, which have a predisposition for enlargement and/or apoplexy over time.

36 Medical management with a DA or SST analog can also be considered in the appropriate clinical setting but is typically ineffective.

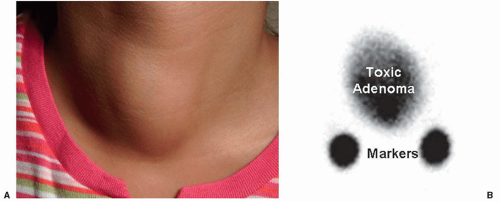

Thyroid-stimulating Hormone-secreting Adenomas (Thyrotroph Adenomas). PAs secreting thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) are diagnosed because of elevated thyroxine and triiodothyronine levels and a nonsuppressed (and often elevated) TSH in the presence of a pituitary tumor on MRI. These tumors usually secrete excessive quantities of α-subunit, and the ratio of α-subunit to TSH is high, allowing for this diagnosis to be distinguished from pituitary resistance to thyroid hormone.

37 Medical treatment includes SST analogs and DA, in addition to interventions directed at controlling the hyperthyroidism.