Endocrine Tumors

Steven Duffy

Keith Goldstein

Stephen L. Graziano

CHEMOTHERAPY OF ENDOCRINE TUMORS

The endocrine tumors include thyroid cancer, adrenal gland tumors, pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas, pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs), and carcinoid tumors.

Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy and over time, it continues to increase in frequency, with 44,760 new cases estimated in 2010, but 1,690 expected deaths.1 Of the new cases of thyroid cancer each year in the United States, approximately 90% are well-differentiated cancers, 5% to 9% medullary tumors, 1% to 2% anaplastic tumors, 1% to 3% lymphoma, and <1% are sarcomas or other rare tumors.2 The well-differentiated tumors include papillary, follicular, and Hurthle cell types, with the papillary subtype predominating. The primary treatment modality for most patients with thyroid cancer is surgery followed by thyroid-stimulating hormone suppression and possibly iodine 131 (131I).

The role of chemotherapy in this disease is largely relegated to the aggressive anaplastic subtype, or other subtypes that have progressed after surgery, radioactive iodine, and radiation therapy. The most studied agent in this disease has been doxorubicin, both as a single agent and in combination. Ahuja et al.3 reviewed 17 trials and almost 250 patients with thyroid cancer who were treated with single-agent doxorubicin and found a composite response rate of 38.3%. The response rate to doxorubicin monotherapy was further broken down to differentiated 38%, undifferentiated 22%, medullary 42%, and Hurthle cell 33%.

Doxorubicin has been used as the backbone of combination therapy with many different agents including bleomycin, cisplatin, vincristine, and melphalan. There has been variable success with the combination of cisplatin and doxorubicin. In a trial by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), the combination had a higher partial and complete response rate particularly among patients with more undifferentiated tumors.4 However, a similar trial by the Southeastern Oncology Group in the 1980s concluded that the combination offered little advantage over doxorubicin alone, but added more toxicity.5

Bleomycin has also been studied extensively in advanced thyroid cancer. As monotherapy, bleomycin appears to have modest activity, with the largest series consisting of 21 patients, of which 9 patients had a response.6 In a series of 8 patients treated by Ahuja et al.3 with various doxorubicin combinations, the only two responses were seen with the combination of doxorubicin and bleomycin. However, other reports have shown no benefit to the combination.7 In addition, the potentially lethal pulmonary toxicity makes this drug less appealing, particularly in older patients.

Paclitaxel is a promising chemotherapeutic agent in thyroid cancer. This drug was the most active agent studied in preclinical systems, including cell lines and xenograft in nude mice.8 Paclitaxel was then tested in the clinical setting with 20 patients in a prospective phase II trial. Patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer were treated with paclitaxel at 120 or 140 mg per m2 as a 96-hour infusion every 3 weeks. Out of 19 evaluable patients, the authors reported an impressive response rate of 53%.9 There was also an observation that several patients with an initial response experienced tumor progression before the next cycle. Because of this, several patients were treated off protocol with 1-hour weekly infusions of paclitaxel and an additional three patients had partial responses. Survival, however, remained poor, with median survival of only 25 weeks. Five patients in this study also went on to receive several additional chemotherapeutic agents including cisplatin, doxorubicin, irinotecan (CPT-11), gemcitabine, docetaxel, and etoposide, none of which produced a clinical response. There was, however, one partial response to thalidomide that lasted approximately 6 months, leading to further study of the activity of this agent. In a phase II trial of the use of thalidomide in a population of patients with rapidly progressive radioiodineunresponsive thyroid cancer (follicular, papillary, insular, or medullary), 36 patients were given thalidomide at a starting dose of 200 mg, up to a maximum of 800 mg per day.10 Of the 28 evaluable patients, there were 5 with a partial response and 9 with stable disease for an overall clinical control rate of 50%. The median survival was 23.5 months for responders and 11 months for nonresponders. The role of thalidomide in the anaplastic subtype, however, remains questionable as preclinical studies with an anaplastic thyroid cancer xenograft model failed to show in vivo activity of thalidomide.11

In addition to thalidomide, multiple new agents are being investigated in this disease and are in various stages of clinical development. As thyroid cancer is a vascular tumor, vascular disrupting agents have been the target of ongoing research. Such agents include combretastatin A-4, SU5416, bevacizumab, sorafenib, sunitinib, axitinib, and motesanib.12 Among the more promising agents is sorafenib which, in a phase II trial, was given to 30 patients with metastatic, iodine refractory thyroid cancer and demonstrated a clinical benefit rate (partial response + stable disease) of 77% with a median progression-free survival of 79 weeks.13 In a phase II study that

was presented in abstract form, 43 patients were treated with 50 mg of sunitinib on a 4-weeks on/2-weeks off schedule.14 Of the 31 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer, 13% had a partial response and 68% had stable disease. In the patients with medullary thyroid cancer, 83% had stable disease. Axitinib, which is a selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) 1, 2, and 3, was studied in a multi-institutional phase II trial in patients with advanced thyroid cancer that was not amenable to surgery or radioactive iodine.15 Of the 60 patients enrolled, 16 (30%) had a partial response and 23 (38%) had stable disease lasting 16 weeks or more. The median progression-free survival was 18.1 months. Motesanib is an oral inhibitor of VEGF receptors, platelet-derived growth-factor receptor, and KIT. Motesanib was studied in a recent phase II study trial of 93 patients with progressive differentiated thyroid cancer.16 Although the objective response rate was only 14%, the rate of stable disease was 67%; 35% of stable disease patients had disease control lasting for 24 weeks or longer. Other drugs that have shown promise are farnesyl transferase inhibitors, such as manumycin, and the histone deacetylase inhibitors suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid and m-carboxycinnamic acid.17,18 These drugs appear to have single-agent activity as well as sensitize thyroid cancer cells to chemotherapy. More recently, fosbretabulin (CA4P), a reversible tubulin binding tumor vascular disrupting agent, has been used in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel to treat patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer.19 Preliminary data presented in abstract form show a 17% improvement in overall survival versus carboplatin and paclitaxel alone.

was presented in abstract form, 43 patients were treated with 50 mg of sunitinib on a 4-weeks on/2-weeks off schedule.14 Of the 31 patients with differentiated thyroid cancer, 13% had a partial response and 68% had stable disease. In the patients with medullary thyroid cancer, 83% had stable disease. Axitinib, which is a selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) 1, 2, and 3, was studied in a multi-institutional phase II trial in patients with advanced thyroid cancer that was not amenable to surgery or radioactive iodine.15 Of the 60 patients enrolled, 16 (30%) had a partial response and 23 (38%) had stable disease lasting 16 weeks or more. The median progression-free survival was 18.1 months. Motesanib is an oral inhibitor of VEGF receptors, platelet-derived growth-factor receptor, and KIT. Motesanib was studied in a recent phase II study trial of 93 patients with progressive differentiated thyroid cancer.16 Although the objective response rate was only 14%, the rate of stable disease was 67%; 35% of stable disease patients had disease control lasting for 24 weeks or longer. Other drugs that have shown promise are farnesyl transferase inhibitors, such as manumycin, and the histone deacetylase inhibitors suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid and m-carboxycinnamic acid.17,18 These drugs appear to have single-agent activity as well as sensitize thyroid cancer cells to chemotherapy. More recently, fosbretabulin (CA4P), a reversible tubulin binding tumor vascular disrupting agent, has been used in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel to treat patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer.19 Preliminary data presented in abstract form show a 17% improvement in overall survival versus carboplatin and paclitaxel alone.

Medullary thyroid cancers are derived from the parafollicular cells and do not concentrate iodine, making radioactive iodine treatments ineffective. The natural history of this subtype is variable, but patients can survive for years with metastatic disease.20 Chemotherapy trials in this subtype are limited by the low incidence of the disease, and they are often included in other advanced thyroid cancer trials. The standard options for thyroid cancer such as doxorubicin and cisplatin appear to have limited activity in the medullary subtype.4 Alternative regimens appeared more promising, beginning with the report of one patient with metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma who had a complete response to the combination of dacarbazine and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).21 This regimen was confirmed to be active, with three out of five patients achieving a partial response that lasted >8 months.22 In a larger study, 20 patients received alternating 5-FU/streptozocin and 5-FU/dacarbazine, which produced 3 partial responses and 11 stabilizations.23 Subsequently, a similar regimen using alternating doxorubicin/streptozocin and 5-FU/dacarbazine also showed impressive efficacy, with three partial responses lasting >18 months, and 10 stabilizations lasting between 8 and 51 months.24 The regimen of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine (CVD) has also shown moderate activity.25 Alternatives to chemotherapy, such as octreotide and interferon, have also been used in this disease. These drugs have been most effective at reducing symptoms related to elevated calcitonin levels. The combination of interferon α-2B 5 million units three times a week, along with octreotide 150 to 300 µg daily, produced no objective tumor responses but five of seven patients with severe diarrhea had symptomatic relief.26 There is encouraging preclinical data using a yttrium-90 (90Y) labeled to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in combination with single-agent dacarbazine or combination chemotherapeutic regimens.27 A similar antibody to CEA, which is attached to 131I also, shows promising efficacy as well. The agent was synergistic with different chemotherapeutic regimens.28

In addition, growing clinical evidence suggests that small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sorafenib, vandetanib, motesanib, sunitinib, and XL-184 may be of benefit in this disease.29 In a recent single arm, phase II, study in patients with progressive or symptomatic, advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer, 91 patients were given motesanib at a dose of 125 mg per day.30 Although only 2% of patients achieved an objective response, 81% of patients had stable disease, with 48% having stable disease for ≥24 weeks.

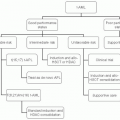

In conclusion, metastatic and progressive thyroid cancer that is not amenable to surgery, radiation therapy, or radioactive iodine, generally carries a poor prognosis. Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been given with fairly disappointing results. However, further understanding of the molecular biology of this disease and recent trials with vascular disrupting agents, specifically small-molecule kinase inhibitors, have changed the way this disease is treated. For the patient with differentiated thyroid cancer, it is reasonable to give sorafenib or sunitinib as first-line, then use doxorubicin-based chemotherapy on progression. For medullary thyroid cancer, small-molecule kinase inhibitors are also acceptable, but it would be more reasonable to use dacarbazine-based chemotherapy at the time of failure of kinases. Unfortunately, cytotoxic chemotherapy, usually with doxorubicin, still remains the backbone of treatment for anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare disease, with an incidence of only two per million people worldwide. Adrenal adenomas are much more common and are often difficult to differentiate from their malignant counterpart. In general, carcinomas produce abnormal amounts of androgens and 11-deoxysteroids, but they can also produce abnormal amounts of cortisol, aldosterone, or they can produce no abnormal hormones at all.31 Surgery remains the primary therapy, with the goal of complete resection and cure. However, many patients will not be cured because of microscopic residual disease or the inability to completely resect the tumor. In these patients, and those with metastatic disease, systemic treatment is often used.

Mitotane, or o,p′-DDD, is a potent adrenocorticolytic agent, which acts through the inhibition of cortisol and pregnenolone synthesis.31 As the drug is adrenocorticolytic, it is typically given with hydrocortisone to prevent adrenal insufficiency. It has been used in the adjuvant as well as advanced disease setting, either alone or in combination with other agents. The benefit of mitotane in the adjuvant setting remains controversial, largely because of the lack of randomized, controlled trials. Mitotane has been evaluated in multiple retrospective and small phase II trials, however. In the largest adjuvant series,

59 patients from Poland were treated with mitotane either immediately after surgery or with delayed treatment. With long-term follow-up, 18 out of 32 patients were alive in the group that received immediate treatment, versus only 6 out of 27 patients who received delayed treatment.32 The combination of mitotane and streptozocin was also found to be beneficial when given after complete resection. Among 28 patients, 17 of whom were treated with adjuvant oral mitotane and intravenous(IV) streptozocin (1 g a day for 5 days followed by 2 g every 3 weeks), there was a statistically significant improvement in disease-free survival.33 However, other series have found less benefit from adjuvant mitotane. In an analysis of >250 patients treated in Paris, mitotane was not found to be beneficial in the patients who underwent a surgical resection with curative intent.34 The experience at MD Anderson of 139 patients treated since 1980 found that 5-year survival had improved to 60%, compared with 30% in a previous trial between 1950 and 1981. However, this difference could not be attributed to the use of mitotane. The improved outcomes were thought to be because of better surgical techniques and supportive care.35

59 patients from Poland were treated with mitotane either immediately after surgery or with delayed treatment. With long-term follow-up, 18 out of 32 patients were alive in the group that received immediate treatment, versus only 6 out of 27 patients who received delayed treatment.32 The combination of mitotane and streptozocin was also found to be beneficial when given after complete resection. Among 28 patients, 17 of whom were treated with adjuvant oral mitotane and intravenous(IV) streptozocin (1 g a day for 5 days followed by 2 g every 3 weeks), there was a statistically significant improvement in disease-free survival.33 However, other series have found less benefit from adjuvant mitotane. In an analysis of >250 patients treated in Paris, mitotane was not found to be beneficial in the patients who underwent a surgical resection with curative intent.34 The experience at MD Anderson of 139 patients treated since 1980 found that 5-year survival had improved to 60%, compared with 30% in a previous trial between 1950 and 1981. However, this difference could not be attributed to the use of mitotane. The improved outcomes were thought to be because of better surgical techniques and supportive care.35

Attempts have been made to improve on standard mitotane treatment. At the standard dose of 6 to 10 g a day, mitotane has been shown to be effective at controlling symptoms, without a clear effect on survival.36 One reason for the disappointing results may be poor compliance to therapy because of intolerable side effects. The main side effects are related to either the gastrointestinal tract or the nervous system. Terzolo et al.37 attempted to reduce side effects by starting at a low dose, and backing off further when blood levels reached 14 to 20 µg per ml.37 In this small series, only one of eight patients discontinued therapy because of side effects, with three out of four patients having a significant hormonal response.

Another attempt to improve on mitotane therapy has been to combine it with chemotherapy. The combination of cisplatin 40 mg per m2 days 5 through 7, etoposide 100 mg per m2 days 5 through 7, doxorubicin 20 mg per m2 days 1 and 8, and daily mitotane was evaluated by Berruti et al. They showed an overall response rate of 53.5% and time to progression (TTP) for responders of 24.4 months.38 A hormonal response was seen in 9 of 16 evaluable patients. The additional side effects from the mitotane required a lower dose than the planned 4 g a day in most patients, but the regimen overall was well-tolerated. The combination of cisplatin and mitotane was also evaluated by the Southwest Oncology Group. In this phase II study, cisplatin was given at either 75 or 100 mg per m2, along with mitotane at 4 g a day. The overall response rate was 30%, with an overall survival of 11.8 months. Toxicity was considered significant, with 22% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 nausea and vomiting.39 Infusional doxorubicin, vincristine, and etoposide along with mitotane have also been evaluated in the phase II setting. In 35 patients, a response rate of 22% was observed, which included 3 minor responses.40 Neutropenia was a problem, with 66% of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4. In this study, they attempted to push the dose of mitotane to achieve levels >10 µg per ml. The median mitotane dose was 4.6 g per day, with no improvement in response, or overall survival in patients achieving a higher serum concentration.

The identification of other chemotherapeutic agents has been difficult because of the relatively low response rates that are seen in adrenocortical carcinoma. It is theorized that the strong expression for multidrug resistance (MDR) gene has limited the effectiveness of most cytotoxic agents.40 However, moderate activity has been seen with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-FU, etoposide, and cisplatin. Resistance to doxorubicin is by different mechanisms than the MDR gene, and it does have limited activity as a single agent, as shown by the ECOG. In a series of 52 patients, doxorubicin, at a dose of 60 mg per m2, yielded a response rate of 19% when given as first-line therapy. However, when doxorubicin was given to patients who had first failed mitotane, there were no objective responses.41

Another agent that has been studied as a single agent is cisplatin. Cisplatin has an advantage over many other cytotoxics in that resistance to the drug is not felt to be related to the MDR gene.42 Cisplatin was initially noted to have activity as a single agent, with responses lasting between 4 and 9 months in small series of patients.43,44 When given along with mitotane, response rates were 30%.39 Combination therapy has generally focused around these two agents, cisplatin and doxorubicin. The most common combinations are these two drugs with the addition of either cyclophosphamide or 5-FU. The CAP regimen (cyclophosphamide 600 mg per m2, doxorubicin 40 mg per m2, and cisplatin 50 mg per m2) has been evaluated in 11 patients and showed a response rate of 18% and a median survival of approximately 10 months.45 The addition of 5-FU to higher doses of cisplatin and doxorubicin produced a similar response rate of 23%.46 The combination of vincristine, cisplatin, teniposide, and cyclophosphamide showed activity in patients who had failed adjuvant mitotane and streptozocin.47 In this difficult patient population, 11 patients received treatment for a median of 6 months, with 2 patients achieving a partial response and 7 patients having stable disease. The median survival was 21 months from the start of combination chemotherapy. Single-agent irinotecan has also been studied, but with no responses in the 12 patients treated and stable disease in 3.48

In conclusion, adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare cancer with a very poor prognosis. The mainstay of systemic therapy for the last 40 years has been mitotane, which controls hormone secretion in up to 60% of patients. There is no clear gold standard for the treatment of this disease; as such, the FIRM-ACT trial is under way in order to compare etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitotane to streptozotocin and mitotane.49 For patients with refractory adrenocortical carcinoma, there is also a phase II clinical trial underway to assess the response rate to sunitinib.50 The incorporation of newer chemotherapeutic agents will be a continuing challenge given the rarity of this disease. Recent advances in molecular biology, however, have enhanced our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the development of adrenocortical cancer and have the promise of guiding development of future therapies.

Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas

Pheochromocytomas, and their extra-adrenal counterpart’s paragangliomas, are rare tumors that arise from the sympathetic

paraganglia.51 These tumors typically secrete catecholamines and can cause severe, episodic hypertension. The estimated incidence is 1/100,000 adults per year.52 Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas, and 15% to 35% of paragangliomas, are considered malignant.53 The ability to differentiate between malignant and benign is often difficult. The distinction is usually made based on local invasion, or the presence of distant metastases.54 Although benign tumors do not typically alter long-term survival, malignant pheochromocytomas have a 5-year survival of approximately 44%.51 The primary therapy for these tumors is surgery. However, patients with metastatic disease require additional therapy.

paraganglia.51 These tumors typically secrete catecholamines and can cause severe, episodic hypertension. The estimated incidence is 1/100,000 adults per year.52 Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas, and 15% to 35% of paragangliomas, are considered malignant.53 The ability to differentiate between malignant and benign is often difficult. The distinction is usually made based on local invasion, or the presence of distant metastases.54 Although benign tumors do not typically alter long-term survival, malignant pheochromocytomas have a 5-year survival of approximately 44%.51 The primary therapy for these tumors is surgery. However, patients with metastatic disease require additional therapy.

Radiation is a viable option for relief of painful bone and lymph node metastases but has limited value in control of hormonal secretion or in widely metastatic disease.55,56 Other treatment options include single-agent or combination chemotherapy or radioactive isotopes. Several drugs have shown activity in malignant pheochromocytomas in small case series, including cisplatin, 5-FU, and paclitaxel.57,58 However, the most active regimen appears to be the combination of CVD. This regimen was adopted because of its activity in neuroblastoma, where response rates of 80% were seen.59 The regimen was tested in 14 patients with malignant pheochromocytomas at the National Institutes of Health. The regimen consisted of cyclophosphamide 750 mg per m2, vincristine 1.4 mg per m2, and dacarbazine 600 mg per m2 for 2 days, in a 21-day cycle. The overall response rate was 57%, with a median duration of >22 months. Biochemical responses were seen in 79% of patients and appeared to correlate with increased quality of life as the Karnofsky performance status improved from a mean of 70% to a mean of 95%.60 Several subsequent small case series confirmed that this regimen was active.61,62 When patients progress on the CVD combination, data for salvage chemotherapy are limited. Paclitaxel, however, was able to achieve a partial biochemical response, and significant improvement in symptoms in one patient who had progressed after receiving CVD, as well as cisplatin and etoposide.58

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree