ENDOCRINE REPLACEMENT THERAPY

Part of “CHAPTER 17 – HYPOPITUITARISM“

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

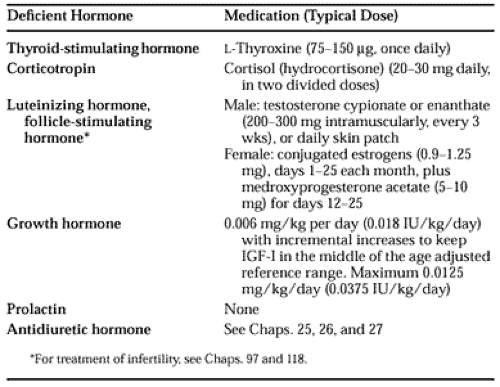

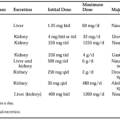

Hypopituitarism can be an exceptionally satisfying condition to treat; most of its endocrine signs and symptoms can be completely relieved by suitable hormone replacement therapy. There are two general principles for prescribing a replacement regimen. First, the physician should perform suitable testing and treat only patients who are demonstrably borderline or deficient. Second, when there is failure of an endocrine target gland (e.g., thyroid, adrenal, gonad), regardless of whether the deficiency is primary or secondary, the physician should replace the target-gland hormone (e.g., cortisol) rather than the corresponding pituitary hormone (e.g., ACTH). Table 17-6 lists some commonly used endocrine replacement medications and typical adult doses.

When testing demonstrates borderline-low secretion of a hormone, particularly cortisol, in an asymptomatic patient, it is unclear whether the patient should be treated. Many patients with lower-than-normal glucocorticoid secretion can tolerate even a major stress adequately, but, if possible, it is prudent not to take this risk. If the baseline serum cortisol concentration is borderline deficient, some physicians believe that extended treatment is better because the patient acquires the habit of taking glucocorticoid and may be more likely to think of increasing the dose appropriately at the time of an intercurrent illness. Others prefer to have the patient keep a supply of cortisol at home and take it only for intercurrent illness. The choice of treatment plan should be individualized.

More informed choices can be made if the physician becomes familiar with local costs of the various relevant diagnostic tests and of medications. In general, the costs of maintenance endocrine medications are low and are not of significant economic concern,

with the exceptions of GH therapy and gonadotropin treatment to promote fertility. For long-term follow-up, the most cost-effective strategy is to minimize hospitalizations. A central part of this strategy is to schedule follow-up office visits every 6 to 12 months after the patient is clinically stable. At these visits, the physician can answer questions and continue to educate the patient about his or her disease, as well as maintain a good rapport with the patient. This will increase the likelihood that the patient will phone for advice at a time when prompt treatment of an intercurrent illness can help prevent complications and hospitalization.

with the exceptions of GH therapy and gonadotropin treatment to promote fertility. For long-term follow-up, the most cost-effective strategy is to minimize hospitalizations. A central part of this strategy is to schedule follow-up office visits every 6 to 12 months after the patient is clinically stable. At these visits, the physician can answer questions and continue to educate the patient about his or her disease, as well as maintain a good rapport with the patient. This will increase the likelihood that the patient will phone for advice at a time when prompt treatment of an intercurrent illness can help prevent complications and hospitalization.

GLUCOCORTICOID REPLACEMENT

Cortisol (i.e., hydrocortisone) or cortisone can be used for replacement therapy. Cortisone is converted to cortisol after ingestion. Cortisol is the predominant glucocorticoid secreted by the human adrenal gland, and an adult produces ˜10 mg daily in the unstressed state.42 There is a diurnal rhythm, with greater secretion in the morning and less in the evening. The serum half-life is ˜1 hour.

When cortisol is used for adrenal replacement in the adult, it is commonly given in dosages of 30 mg daily; for example, 20 mg each morning and 10 mg each afternoon or evening. For smaller individuals, 20 mg daily is sufficient (e.g., 10 mg twice daily). This cortisol dosage exceeds normal daily adrenal secretion, but there are losses in absorption; also, undoubtedly, one to three doses daily is a less efficient mode of administration than the more continuous natural secretion. In the occasional patient who cannot reliably remember to take more than one dose daily, it may be best to give the entire dose in the morning (rather than risk undertreatment), or to use a glucocorticoid with a longer pharmacologic half-life. Some authors suggest every other day therapy. Cortisone is used interchangeably with cortisol, with 25 mg of cortisone considered equivalent to 20 mg of cortisol. Usually, there is little to favor one compound over the other, except habit or price. However, in severe liver disease, cortisol is preferable because the conversion of cortisone to cortisol occurs in that organ. Prednisone also can be substituted for cortisol, using the assumption that 5 mg of prednisone is equivalent to 20 mg of cortisol. Replacement doses of dexamethasone are not well defined, and there is considerable individual variation; the plasma disappearance half-life is longer than 4 hours, and once-daily dosing is often adequate. A typical dose would be 0.5 mg given at bedtime, with a range of 0.25 to 0.75 mg.

Although cortisol can be assayed in blood and urine, such determinations are not particularly useful in determining a replacement dose of cortisol for an individual patient. The serum half-life is short, so that the serum concentration can be above or below the normal range much of the time, even when a patient is responding well to the dose. The free cortisol in a 24-hour urine sample is often elevated on conventional cortisol dosage regimens.

Most patients do well on any of the aforementioned dosage regimens, manifesting no overt evidence of hypoadrenalism or Cushing syndrome. (However, one report suggests that in men with Addison disease, commonly used replacement doses of glucocorticoids may be associated with a low bone mineral density.43) Even allowing for the lesser efficiency of intermittent oral administration, it seems likely that the customarily used replacement doses are appropriate for most individuals. If, while using one of these regimens, a patient still has chronic symptoms that suggest hypoadrenalism, the physician should check for medication error or noncompliance. If neither is found, the symptoms are likely to be due to a cause other than hypoadrenalism. Some individuals experience a pleasant “high” with supraphysiologic doses of glucocorticoid, leading them to complain when they are returned to true replacement doses.44 A patient’s desire for euphoria is not a reason to continue higher-than-replacement doses indefinitely.

A patient with untreated or undertreated hypopituitarism potentially may be more vulnerable at the time of an intercurrent illness because of a lack of hormonal homeostatic mechanisms. Before therapy, or if therapy is insufficient, such patients are very sensitive to infections, surgical procedures, or drugs such as sedatives or narcotics. Glucocorticoid doses conventionally are increased for significant physical illness or for operative procedures in an attempt to mimic the normal physiologic response to such situations. Interestingly, studies of patients undergoing operative procedures suggest that conventionally prescribed “stress doses” of glucocorticoid are larger and are maintained for a longer period than usually would be needed to mimic normal cortisol production.45,46 A renal transplantation group reports that they no longer increase baseline immunosuppressive doses of glucocorticoid (5 to 10 mg of prednisone daily), even when patients are stressed by sepsis or surgery, and they believe such doses have been sufficient.47 It is likely that the same would be true for intercurrent illnesses. However, until further data are available, the recommendation is to give conventional stress doses during times of intercurrent illness and perioperatively when there is no known contraindication to that approach. For some situations, however—such as surgery of a diabetic patient whose disease becomes difficult to control on higher glucocorticoid doses, or for a patient who becomes psychotic with high glucocorticoid doses—there are reasons to minimize the dosage. In such a situation, the author gives only the equivalent of two or three times the usual replacement doses on the day of surgery and taper to replacement doses within 3 days in the absence of postoperative complications. The patient should be monitored carefully for possible signs of hypoadrenalism and given supplemental glucocorticoid if indicated. Hypoadrenal symptoms are readily reversed if recognized and treated promptly. Table 17-5 summarizes current recommendations concerning glucocorticoid administration in the presence of intercurrent illness or perioperatively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree