- Diabetes education is an important cornerstone of diabetes care, and supports the philosophy of the chronic disease model.

- Diabetes education improves clinical outcomes, and requires periodic follow-up.

- Time spent with a diabetes educator is the best predictor for improvement in diabetes outcomes.

- Patients and physicians agree that diabetes education is a necessary part of care.

- Being prepared with a variety of educational delivery methods is beneficial and necessary to meet the variety of patient learning styles.

- Understanding educational theories builds a strong base for selecting appropriate approaches to meet the needs of individual patients.

- A written plan developed in collaboration with a patient and their educator and care provider offers more chance of achievement.

Introduction

Diabetes education continues to be cited as a cornerstone of effective diabetes care and supports the philosophy of chronic care models (Table 21.1) [1,2]. It is well established that the practice of diabetes self-management education (DSME) is critical to the care and management of people with diabetes, and that measurable behavior change is the unique outcome of working with a diabetes educator [3,4].

Table 21.1 Definitions

| Diabetes educator: a professional who provides education |

| Diabetes self-management education (DSME): the ongoing process of facilitating the knowledge, skill and ability necessary for diabetes self-care [7] |

| Education: a combination of interactive experiences |

| Instructional curriculum: a deliberate arrangement of conditions, written content, to promote actions towards an intentional goal [20] |

| Learning: An active goal-directed process, transforming skills, knowledge and application of values into new observable behavior |

| MNT: medical nutrition therapy |

| Teaching: a system of actions to bring about learning |

Now more than ever, diabetes educators are being held more accountable for their role in diabetes management. Over time it has become apparent that education standards and a system or framework describing self-care behavior could have an important role in supporting people with diabetes to consider behavior changes that might enhance their quality of life and support better management of their condition. The 2000 Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education [5] and recent 2007 update [6], American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) Standards Development for Outcome Measure [3] and the outcomes model, the AADE7™ Self-Care Behaviors framework [7,8], now provide a common reference for establishing behavior change goals and establishing measurable outcomes. The seven self-care behaviors are: healthy eating; being active; monitoring; taking medicine; problem-solving; reducing risks; and healthy coping.

Background

Standards and educational practice guidelines

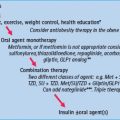

DSME is central to delivering desirable metabolic and clinical care in diabetes. DSME is a comprehensive patient education structure that involves a multidisciplinary team to help achieve the necessary metabolic outcomes and improve the lives of those living with diabetes [9,10]. Metabolic improvements such as glucose, lipids and blood pressure in type 2 diabetes (T2DM) care are best achieved with a healthy lifestyle and appropriate use of pharmacologic interventions.

In 2003, the AADE published Standards for Outcomes Measurement of Diabetes Self-Management Education [3], complementing the National Standards for DSME in 2000 [5]. This publication was subsequently updated and revised in 2007 [6]. These standards offer the educator a program framework, which is based on five evidence-based principles:

This publication clearly identified that behavior change was the unique measurable outcome of diabetes education [3]. In 2004, these self-care behaviors were adopted by AADE leadership, trademarked as the AADE Seven™ [7,8], and have been incorporated into a framework for educators, community leaders and medical professionals to advocate for diabetes self-care management. In addition, this framework provides the potential to be generalized to other chronic diseases and wellness care, and thrives on assessment and documentation.

Educators are guided by professional and discipline-specific scope of practice; these position papers, evidence-based research and standards for diabetes education practise the belief that behavior change can be effectively achieved by using these frameworks.

Three of the main components of DSME are an assessment, intervention and outcomes evaluation of the patient [9,11]. Ongoing collaboration and partnership between the patient and health care professionals is essential for effective DSME. The process involves interactive, collaborative and ongoing education that engages a person with diabetes in therapeutic decision-making [9]. DSME is available throughout the lifespan of the individual with diabetes and enables ongoing reassessment of self-management goals [9]. Diabetes is a progressive disease in which the clinical manifestations vary throughout the patient-lifespan [12]. Changes in stress, acute illness, aging and metabolic abnormalities can impact the clinical manifestations [12]. DSME approaches are typically adjusted as the patient’s lifestyle changes and their condition progresses [9,11].

Also appreciated are the similarities and yet the variety of methodologies and delivery options to assist all people with diabetes and those affected by diabetes to achieve healthier outcomes, including adults, children, parents and older people. The purpose of this section is to introduce the concepts of how to acquire useful self-care information, and change concepts into behaviors that can be useful, measured and maintained over time. Although people with diabetes vary in age, type and duration of diabetes, the principles of education remain the same and are reflected in the following content.

Considering change

The provision of DSME is challenging in any setting, whether outpatient, private practice, community service areas or hospital settings, and is constantly changing. A paradigm shift has occurred in diabetes education. The learner is no longer the “patient,” rather a “person with diabetes.” DSME includes a circle of further learners, and others who are affected by diabetes, such as family members, work colleagues and neighbors. The health care team (nurse, dietitian, pharmacist, physician, other providers) are not just a deliverer of information, with a complacent learner; rather they are “educators” with learners involved in an active “interactive” (go-between) process. In this paradigm, the learners are both the educator and the people involved with diabetes. Each acquires a desire to learn based on need and consider all the alternatives available to them including information, treatment choices and equipment. Both attendee and educator are adjusting to new technologies, and the ever-changing techniques, approaches, settings and fiscal directives.

In addition, researchers on diabetes education programs have adequately demonstrated increased participant knowledge and corresponding improvements in glycemic control [13–16]. The optimal approaches in DSME delivery that are associated with better outcomes focus on behavioral strategies, encourage active engagement of patients, build self-efficacy, use cognitive reframing as a teaching method, are learner-centered and evidence-based where possible [10,17].

Diabetes education is a revered first step in preparing people with diabetes to make the necessary modifications to their lifestyle. Typically, health care professionals teach patients information that they believe is necessary. Evidence indicates, however, that most of the information shared by a health care professional with patients is forgotten soon after. Up to 80% of patients forget what their doctor tells them as soon as they leave the clinic and nearly 50% of what they remember is recalled incorrectly [18]. The Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes, and Needs (DAWN) study indicates that while 50% of persons with T2DM receive DSME, only 16.2% report adhering to the recommended self-management activities [19]. The DAWN study identified key goals that need to be achieved to improve outcomes: reducing barriers to therapy; promoting self-management; improving psychologic care and enhancing communication with health care providers, people with diabetes and their primary care providers that is consistent with educational standards (DSME) previously presented.

This said, the traditional lecture format, with its instructional knowledge-based content outlines, has also changed to involve and evolve using more interactive processes. The new standards for DSME [6] offer the format of “structure, process and outcome” directives for an established program to meet. These formats serve as an influence for third party reimbursement as well as offering the educator a structured evidence-based format for program development, implementation and evaluation. The standards also encourage new opportunities for alternative program involvement of educational options. The nine curricula (Table 21.2) offer the educator a written instructional topic-driven plan for education, and intentionally closely resemble the AADE7 self-management outcome behaviors (Table 21.3). The AADE7 then offers a template for behavior change identification, process for change and evaluation of outcome. New and less experienced providers of education may find adopting these existing formats useful, while experienced educators may reconstruct, adapt and create more unique options. All educators are encouraged to participate in the discovery of alternative and creative activities to engage the learner and provide excitement and variety to their educational delivery methods. Mensing and Norris [20] offer instructional tips and educational skills for both.

Table 21.2 Nine content areas (DSME) [6].

1 Describing the diabetes disease process and treatment options 2 Incorporating nutritional management into lifestyle 3 Incorporating physical activity into lifestyle 4 Using medication(s) safely and for maximum therapeutic effectiveness 5 Monitoring blood glucose and other variables and interpreting and using results for self-management decision-making 6 Preventing, detecting and treating acute complications 7 Preventing, detecting and treating chronic complications 8 Developing personal strategies to address psychosocial issues and concerns 9 Developing personal strategies to promote health and behavior change |

Table 21.3 The AADE7 self-management outcome behaviors. Data from AADE website (www.diabeteseducator.org/AADE7).

1 Healthy eating Making healthy food choices, understanding portion sizes and learning the best times to eat are central to managing diabetes. Diabetes education classes can assist people with diabetes in gaining knowledge, teaching food choice skills, and addressing related barriers 2 Being active Regular activity is important for overall fitness, weight management and blood glucose control. Collaboration between patients, providers and educators best addresses barriers, and helps develop an appropriate activity plan that balances food and medication with the activity level 3 Monitoring Daily self-monitoring of blood glucose provides people with diabetes the information they need to assess how food, physical activity and medications affect their blood glucose levels. Monitoring includes: blood pressure, urine ketones and weight. Education is offered about equipment choices, testing times, target values, and interpretation and use of results 4 Taking medication Diabetes is a progressive condition. The health care team will be able to determine which medications people with diabetes should be taking and help them understand how the medications work. Effective drug therapy in combination with healthy lifestyle choices, can lower blood glucose levels, reduce the risk for diabetes complications and produce other clinical benefits 5 Problem-solving Assistance to make rapid informed decisions about food, activity and medications, and develop coping strategies 6 Reducing risks Effective risk reduction behaviors such as smoking cessation, and regular eye, foot and dental examinations reduce diabetes complications and maximize health and quality of life, available preventive services. These include smoking cessation, foot inspections, blood pressure monitoring, self-monitoring of blood glucose, aspirin use and maintenance of personal care records 7 Healthy coping Health status and quality of life are affected by psychologic and social factors. Coping: a person’s ability to self-manage their diabetes is related to their skills. Identifying the individual’s motivation to change behavior, set achievable behavioral goals and provide support. |

The purpose of this chapter is to offer the educator and their colleagues the ability to review current education practice and to acquire more in-depth knowledge of interventions focusing on self-care behaviors. These behaviors can then more strongly offer information and potential behavior change opportunities based on a set of practices, presented in a curriculum framework.

The new standards and AADE7 frameworks offer educators an approach that is holistic, empowering and opportunities for patients to strengthen their independence and quality of life. The approach also supports a more public health, patient-centered approach for the person with diabetes and the educator.

Patient-centered educational approaches

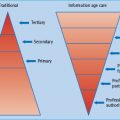

Patient-centered education, or learner-centered education, is now promoted by educators moving from provider-directed to “patient-centered” care and education in line with public health and chronic disease models of illness management. Diabetes educators were early proponents of this model and quickly incorporated strategies to meet the patients’ agenda at each encounter [21].

This more patient-centered approach frees the educator to provide personalized (less didactic) information, encouraging lessons to be learned and then applied into patients’ own lives thereby providing reinforcement and follow-up. As summarized by Funnell [7], patients are more successful if they hear consistent messages and the same single messages from all care providers, educators and team members.

Diabetes education is a first step in preparing patients to make necessary modifications to their lifestyle. As many patients forget much of what is said in clinic, educators and clinicians must recognize the need to involve patients in determining what they feel they need and address this first as a way to engage patients, and improve their retention of information.

The information sharing among health care professionals and retention of information by people with diabetes is not enough to help them to change their behavior. The quality and quantity of effective communication between health care professionals and people with diabetes is the most critical indicator of successful DSME. Increased contact time between health care professionals and patients has been associated with better regimen adherence and glucose reduction [15].

So what is the best way to teach people with diabetes? How do we know that they are learning? What is the evidence supporting the education methods we choose to utilize? A simple elementary school approach from Anna Devere Smith, which “thinks of education as a garden where questions grow,” seems to describe the learner-centered approach applicable for adults with diabetes most aptly [73]. People with diabetes need an appropriate environment where they can share their challenges with their lives with diabetes, ask health care professionals for help with strategies and consequently concord with the prescribed regimen.

The principles of facilitation and patient-centered intervention have been recognized to be superior to a didactic and more passive teaching approach [9,10]. One of the DSME standards states that “there is no one best education program or approach; however, programs incorporating behavioral and psychosocial strategies demonstrate improved outcomes. Ongoing support is critical to sustain progress made by participants during the DSME program” [9]. There is strong evidence that goals generated by patients produce better outcomes than goals that are generated by health care professionals [9].

There are many educational approaches that are utilized by diabetes educators to help patients acquire knowledge, skills and commitment to self-care behaviors necessary for effective diabetes care [9]. Typically, individual adult T2DM education interventions allow the educator to tailor the approach to the patient’s specific needs and consequently provide effective therapy. However, evidence indicates that group diabetes interventions can be more cost-effective, patient-centered and provide interactive learning with a high level of patient satisfaction compatible with individual interventions. The educational approaches and methods utilized in group education differ among diabetes educators. Therefore, further research is needed to determine which educational approach and method utilized by diabetes educators contributes to effective teaching that produces the best clinical outcomes in adults with T2DM. The existing best practices in group education indicate that the best outcomes are produced with an empowerment approach, which focuses on when and what patients want to learn. Problem-based, culturally tailored approaches that include psychosocial, behavioral and clinical issues relevant to the patients’ needs and readiness to learn have resulted in improved outcomes [22].

DSME aligns with a chronic disease model that indicates that educational approaches should be non-complex, individualized to a patient’s needs and lifestyle, reinforced over time, respectful to an individual’ s habits, and should incorporate social support [9,23,24]. Chronic disease care approaches use similar strategies to DSME as they focus on collaborative problem definition, goal-setting, continuum of self-management training and support services [9]. The general consensus on chronic disease interventions indicates that the most beneficial components of education are individualization, relevance, feedback, reinforcement and facilitation [23-25].

How do we provide learner-centered education in a group setting? How do we evaluate everyone’ s unique learning needs and provide individual attention they deserve? The complexity of the individual needs assessment and training in a group setting presents a challenge for effective self-management education. The challenge is to individualize the approaches similar to a typical one-on-one session but in a group session. Successfully individualizing the group session allows the patients to learn, retain their knowledge and be committed to the follow-up action plan. Traditional didactic education that focuses on teaching information through lectures without patients’ engagement has been shown to be ineffective in helping patients change their lifestyle behaviors necessary to improve clinical outcomes [26-28]. Diabetes knowledge does not guarantee changes in behaviors that eventually lead to better outcomes. The learner-centered approach employs non-didactic and less passive strategies in an attempt to promote active engagement in the learning process. A patient-centered education reflects the best practices and theories that have been shown to promote patients’ knowledge retention, commitment and improved self-care outcomes. These include facilitation, empowerment, motivational interviewing, behavioral goal-setting, behavioral and psychosocial strategies, and ongoing support [26–34]. The process allows for the patients to discuss their understanding of diabetes, internalize their commitment and determine their priorities. This process also allows for ongoing implementation of short and long-term goals, which can then be monitored for progress. Patients come up with their own solutions to their own diabetes challenges instead of being told what they should do by the educator. The expectation is that by identifying what is practical and achievable, patients ultimately own their own commitments and will be more likely to accomplish the requisite lifestyle changes [28,35,36].

Effective diabetes education aligns with the principles of adult learning as adults learn most effectively when information is simple, practical and relevant (i.e. directed by their interests), the learning builds on participants’ experiences and there is a focus on application (i.e. when learning is applied to action) [37]. This process of learning involves cognition, emotions and environmental factors that impact knowledge level, skill acquisition and views [38].

Educational theory behind the practice: models and methods

The core foundation of the diabetes education philosophy is that patients are ultimately responsible for their own self-management. The assumption is that patients want to maximize the quality of their life and self-management education [39]. Health care professionals help patients identify ways to make changes necessary for a healthy way of life. Each person with diabetes differs and therefore requires unique lifestyle skill strategies that are applicable to his or her circumstances.

Traditional lecture-based didactic education approaches place the learner in the role of the recipient and the instructor in the role of the “knowledge-giver.” It does not allow the learner to think critically and perceive their own personal and social reality, which are critical steps for adapting to chronic disease [30,31]. DSME allows patients to be part of the decision-making about their self-care and management [32]. Patients develop confidence in making informed decisions about their medical condition and can choose to act on it.

An additional approach that aligns with effective diabetes education methodology is motivational interviewing. This is closely linked with the empowerment theory as it focuses on creating opportunities for patients to come up with their own assessments and set their own goals [33]. Motivational interviewing is another example of a learner-centered intervention that is considered an effective approach to promote patients’ knowledge retention, self-care commitment and improved self-care outcomes [24,33,34].

The proposed theoretical basis evident in a patient-centered diabetes education concept includes the Health Belief Model, the Trans-tiieoretical Model/Stages of Change, Common Sense Model, the Social Learning Theory and the Dual Processing Theory [40-43]. These commonly utilized theories in diabetes education allow for successful communication with patients through fostering effective listening, relationship building and creating an environment of respect and trust. These theories strengthen an educator’s theoretical basis for an effective diabetes education technique. The theories also reflect on the approaches utilized to promote a meaningful dialogue with those involved in diabetes education. The theories help to integrate concepts better for a wider variety of individuals, regardless of age, gender or ethnicity.

Theory: the Health Belief Model

The Health Belief Model is a psychologic framework that outlines predictable health related behaviors [40]. People’s life experiences and exposures to past events shape their perception of susceptibility, severity, barriers, benefits and cost of adhering to prescribed interventions. The process of diabetes education should allow for an effective discussion and exploration of beliefs which is needed to promote appropriate self-care. Without an adequate Health Belief Model patient assessment, patients may lack the necessary motivation to overcome their belief barriers.

Theory: the Stages of Change Model

Learning and making changes in one’s lifestyle is a process of adjusting what can be done, when and how. The multiple interactions with patients allow diabetes educators to guide them to transition with their commitments to make the change. The Prochaska’s Stages of Change Model [44] outlines the predicable process of change as patients not only learn what they are ready to learn, but also understand the reasons behind the need for change and strategies. The Stages of Change Model illustrates the five stages in a continuum of behavior change: pre-contempla-tion, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance and relapse [44]. Each stage has an important role in supporting an evolutionary process whereby learners recognize the need for change, act, evaluate and react.

Diabetes educators can help patients to increase their realization of importance of change, confidence, and readiness by asking meaningful questions. Importance of change can be addressed by asking why? Is it worthwhile? Why should I? How will I benefit? What will change? At what cost? Do I really want to? Will it make a difference? By asking how and what diabetes educators can help patients to evaluate their confidence to change. Consider asking, can I? How will I do it? How will I cope with…? Will I succeed if…? What change…? When assessing readiness, start asking when? Should I do it now? How about other priorities? [45].

Theory: the Common Sense Model

The theoretical framework of the Common Sense Model is based on the balance of danger and fear control [40]. This theory implies that people will not self-regulate unless there is a significant and relevant understanding of the condition, cause, disease timeline, consequences, curability and controllability. The internal cognitive representation of the illness is balanced by emotions that require effective coping skills and appraisal.

The first component of the five assumptions in the theory is that patient identifies the condition. The second is the patient-perception on what actually caused the condition. The third consideration is of a timeline and how long the patient thinks that the condition is going to last. The fourth component of the Common Sense Model is the patient’s understanding of the consequences of the disease and how it will affect their future. The fifth component relates to a patient-perception of treatment effectiveness [40]. The perceived vulnerability to diabetes complications is more significant among patients who have witnessed severe complications among people they know, such as family members or loved ones [46]. Witnessing and getting to know other patients in a group setting with varied levels of diabetes complications can allow people to internalize the necessary steps to control their condition more effectively.

Theory: the Social Learning Theory

The foundation of the group education session is a discussion among patients that allows them to learn from one other. The Social Learning Theory outlines the social context necessary for role modeling. It also asserts that the inspiration and support generated by group interaction helps patients change their behaviors [41]. Both social interactions and psychologic factors influence learning. According to Bandura [47]: “Learning skills is not enough, individuals should also develop confidence in the skills that they are learning. Success is not necessarily based on the possession of the necessary skills for performance; it also requires the confidence to use these skills effectively.”

Theory: the Social Cognitive Theory

In the attempt to turn the Social Learning Theory into an observational behavior that the educator can witness, four categories can be derived from the Social Cognitive Theory [47]. In terms of the educator’ s role, these four categories can illuminate the behaviors seen within the group education session. The first characteristic is the role of the facilitator who creates an environment for a successful experience. The second is role modeling through various experiences whereby the educator observes others’ performance. The third is verbal persuasion, where the facilitator skillfully summarizes the information, acknowledges the situation and participants’ beliefs, indicating that the problem can be managed. The facilitator actively encourages people to be verbally explicit when elaborating on their management and future choices. The final aspect involves physical and affective state of identification of physical and emotional sources of symptoms. The facilitator acknowledges and/or responds to emotional utterances by the participants [47].

Theory: the Dual Processing Theory

The Dual Processing Theory relates to a patient’s individual understanding of the medical condition by allowing the learner to discover his or her own solutions. The theory dictates the need to involve patients actively in the learning process [42]. The Dual Processing Theory has two actions, such as activation of a mental representation of an issue and its interpretation based on mental retrieval of events and feelings related to it [43]. The effective group education needs to allow a learner to discover his or her own solutions which increases the patient’s understanding of their medical condition.

Effective diabetes group education approaches use facilitation instead of traditional didactic teaching to produce effective learning [26-28]. The health care professional is responsible for managing the group dynamics and the scope of the group’s conversation. Participants are responsible for addressing issues of relevance to their diabetes management and developing strategies to care for themselves better.

Productive diabetes education strategies utilize the best in adult education methodology that allows for patient engagement. Learning theories demonstrate that adults learn best what is personally applicable and important to them [31]. Without a meaningful learning experience, they may ignore or dismiss the presented information. Also, adults learn best in social circumstances rather than classroom settings [32]. Adults prefer to learn from discussion, incorporation of life experiences and other interactive approaches over lecture, print, computer-based or audiovisual presentations [33,48]. Effective learning activities for adults should involve participants in the learning process, motivate, promote self-determination, meet the learning needs, allow the sharing of personal knowledge and experiences, promote competence, reinforce positive behaviors and help adults to identify consequences of behaviors [32,49].

Curriculum

There are many DSME curricula available for the diabetes educator to choose that can be integrated as a complementary tool to the existing DSME curriculum or can be used as a stand-alone approach. However, most of the curricula have not been validated with sound research and studies. Many of the available curricula utilize evidence-based approaches in diabetes selfmanagement education but as an independent approach have not been validated.

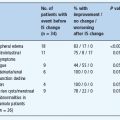

An example of a reliable and valid curriculum has been carried out in a study by Kulzer et al. [26], which compared three diabetes educational methods and their effect on clinical indicators. The three educational approaches were:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree