Economics of Radiation Oncology

ECONOMICS OF LOCOREGIONAL FAILURE

ECONOMICS OF LOCOREGIONAL FAILURE

In 2012, 1,618,910 patients were diagnosed with cancer and 577,610 deaths were recorded.1 Of those who succumbed to cancer, half had a component of local or regional failure. As systemic therapy improves, consequences of local failure become more pronounced.2,3 Improving systemic therapy may lead to a longer lifetime free of systemic metastasis during which local failure can occur. This is one reason that postoperative radiation treatment improves survival in breast cancer, small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, and rectal cancer.1–3 The cost of regional failure in terms of human life and tragedy is staggering.

UNDERSTANDING MEDICARE

UNDERSTANDING MEDICARE

For patients who have Medicare as their primary insurance (these are the majority of radiation oncology patients), Medicare has a predetermined fee that is paid for each medical procedure, billed as a CPT (Current Procedural Technology) code. Medicare pays 80% of this allowable, and the patient’s secondary insurance pays the remaining 20%. Charges are electronically billed, and turnaround time to receive payment can be as few as 14 days. Some secondary insurances will take between 6 and 9 months to pay the final 20%. Many secondary insurances must be billed using a paper claim sent through the mail instead of an electronic claim, thus delaying payment for up to 6 months.4

Hospital-owned, hospital-based radiation oncology practices bill under Medicare Part A. This provides for a technical component of radiation treatment delivery for the hospital; the professional component for physician services is billed separately by the radiation oncologist, also under Medicare Part A. The basis on which the technical component is paid to the hospital is called an ambulatory payment classification (APC). APC groups have different payments based on the complexity of radiation treatment delivery. The payments under the APC classification compared to those paid to outpatient free-standing facilities vary widely. For example, radiation treatment delivery for intensity-modulated radiation treatment, code 77418, is paid to the hospital under Medicare Part A at considerably less than the rate paid to free-standing centers under Medicare Part B. Alternatively, code 77370, special medical physics consultation, is paid to the hospital at approximately twice that paid to a free-standing facility.4

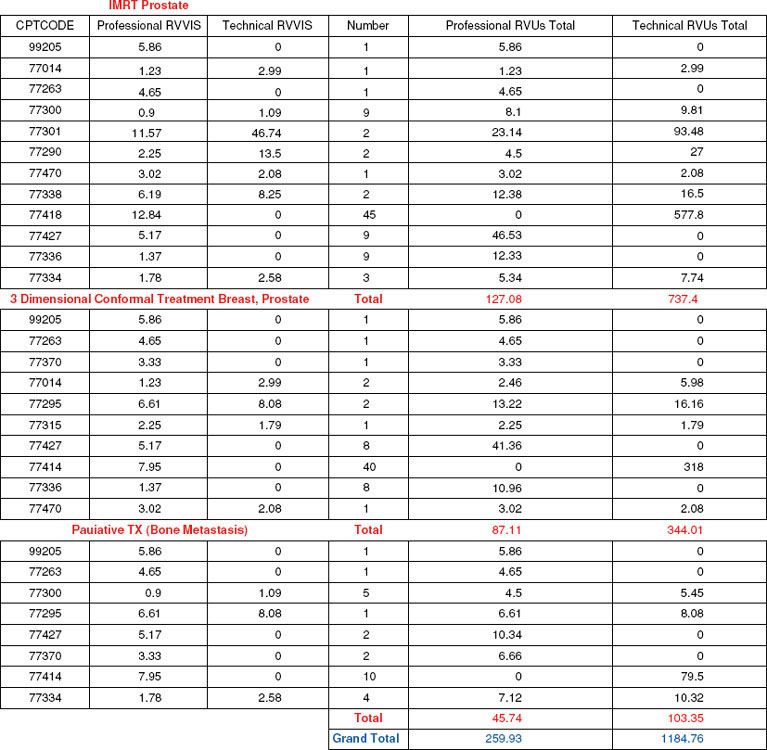

For a free-standing radiation oncology center, Medicare Part B is billed and a global fee is paid. This global fee combines both the professional fee to the physician and the technical fee to the equipment owner in one bundled payment. Some (CPT) codes have a professional component only, and some codes have a technical component only. Other codes have both professional and technical components, indicating that the physician and the equipment owner split this code based on their investment of physician time or equipment ownership. Calculating the professional/technical “split” in an outpatient facility can be difficult and depends on the payer mix, as well as the complexity of patients treated. The professional/technical split is calculated using the relative value units (RVUs) assigned to each CPT code. The RVUs are units of work assigned by Medicare, with each unit of work having a standard reimbursement. The RVUs in the professional/technical split are shown in Figure 100.1 and, as can be seen, vary depending on the complexity and objective of treatment. Calculating the professional/technical split is often difficult for physicians who are in free-standing centers and eligible to receive the professional component. In general, the professional component of global collections is approximately 11% to 35%, depending on the payer mix. If we consider equal rates of IMRT, 3D, and palliative treatment courses, the professional component of the global collections under Medicare Part B is 22%.

FIGURE 100.1. Medicare relative value units broken out by professional and technical classification per radiation treatment course.

SUSTAINABLE GROWTH RATE VERSUS MEDICAL ECONOMIC INDEX

SUSTAINABLE GROWTH RATE VERSUS MEDICAL ECONOMIC INDEX

Medicare Part B (physician services) provides an annual update in allowable charges based on the gross domestic product called the sustainable growth rate (SGR). From the years 2000 through 2011, this has required a reduction in Medicare payment and thus Medicare-allowable fees. These cuts have been forestalled by Congress on multiple occasions.5

The Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is an annual update for Medicare Part A (hospital services) that is based on the rate of medical inflation. This has resulted in a yearly increase in payments to hospitals based on their self-reported rate of Medicare inflation.6 If physician services were paid according to the MEI, we would be reimbursed at 40% more than we are now.

APPEALING DENIED MEDICARE CLAIMS FOR RADIATION ONCOLOGY

APPEALING DENIED MEDICARE CLAIMS FOR RADIATION ONCOLOGY

In January 2006 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reduced the maximum time for adjudicating appeals for denied claims from a maximum of 1,000 days to 300 days. Nearly 20% of processed Medicare claims are denied. However, only 5% of denied Medicare claims are appealed.7,8

Physicians succeed in appealing payment denial in more than 60% of cases, indicating that the appeals process can be successful. If resubmitting the first rejection does not resolve the problem, the first level of appeal is called a fair hearing, and is usually conducted by telephone. You simply need to write a letter to the Medicare carrier requesting a fair hearing. The minimum denied amount needed to appeal a denied claim is $100. Multiple denied claims on different patients can be bundled together as long as the appeal amount is >$100. Include the appropriate documentation with the total amount appealed and CPT book definitions to describe what medical care was rendered and why you should be paid. Much to your surprise, most of the reviewers are not familiar with radiation oncology coding or the CPT coding books. Your job is to teach the reviewers to do their job and pay you.

For the carrier who habitually denies the same code, a previous favorable ruling may get the same code paid over and over again. In this situation, your goal is to use the last favorable ruling as evidence that the same denied code should be paid. This actually works, and sometimes the Medicare carrier will just pay the bill without the hearing as described earlier.8

For all fair hearings, the Medicare carrier is required to give you a written decision within 90 days. If the fair hearing process results in additional denial, the next step is a hearing before an administrative law judge. This is much more formal, and likely you should consider having legal representation. During the fair hearing process, the hearing officer will allow you to explain why a patient needed the (denied) care and provide documentation that you were able to help the patient based on available clinical evidence. During an administrative law hearing, the judge is only interested in whether the law allows you to be paid or not. Do not be afraid to try the appeals process if you feel the denial is inappropriate, and again, most often you will win.7,8

MEDICARE MEDICALLY UNLIKELY EDITS

MEDICARE MEDICALLY UNLIKELY EDITS

A medically unlikely edit (MUE) is a limit on the number of units of a CPT code that would be reported for a patient in 1 day.9 Medically unlikely edits were developed based on clinical judgment, and these were reviewed by insurance medical directors of Medicare and/or Medicare intermediary insurance companies. MUEs are used to screen out too many units of service done in a single day. For example, an appendectomy can only be done once on a patient in 1 day (or ever), and reporting two appendectomies in the same day of service would be impossible. Medicine as a profession can expect Medicare to pass more medically unlikely edits in the future.9 These are often adopted by private insurance programs as well. MUEs apply to a number of procedures in radiation oncology, including dose calculations (code 77300), device charges (code 77334), and IMRT plans (code 77301), and for medical oncology limits in the total quantity of drugs that can be administered. If you find yourself the victim of not being paid due to medically unlikely edits, the first level of appeal as described earlier is a fair hearing, and the next level of appeal is an administrative law hearing. There is no prohibition for additional payments if clinically necessary.

BUNDLING EDITS

BUNDLING EDITS

Medicare and some managed care organizations “bundle” procedures together so that only one charge is paid rather than two separate charges. For example, weekly physics management (code 77336) may not be able to be billed on the same day as special medical physics consultation (code 77370). The managed care organization may think that the special medical physics consultation is bundled into the weekly physics management.10 It is essential to understand what these bundled codes are and where they conflict. Many times, this information is difficult to obtain during the contracting process. The best time to find out about bundling edits is before you sign an insurance contract. It is important to have a well-trained billing staff so that they can understand which codes are bundled, and decisions need to be made regarding a patient’s care as to what specific service is required on a specific day. A sudden billing denial may herald new bundling edits.

Effective January 1, 2010, code 77338 replaced device charge 77334 used for each multileaf pattern for Medicare patients receiving IMRT. This code is used one time per IMRT plan (77301) and replaces multiple charges for multileaf patterns. Unfortunately, the reimbursement for this code is below what would be reimbursed under the prior system. Prior to 2010, if a head and neck cancer patient received a 10-beam, 10-gantry-angle IMRT treatment, code 77334 was billed for a quantity of 10 separate multileaf patterns used in treatment. Currently, code 77338 replaces all of these charges and can only be billed with a quantity of one, not 10. In Florida, in 2011, reimbursement for code 77338 is $459 and for code 77334 is $145. Thus, one charge of code 77338 represents 3.2 charges of code 77334, enough to pay for only 3.2 of the multileaf patterns for the aforementioned head and neck cancer patient.

INSURANCE REQUIREMENTS FOR PREAUTHORIZATION FOR RADIATION TREATMENT

INSURANCE REQUIREMENTS FOR PREAUTHORIZATION FOR RADIATION TREATMENT

A more recent feature of private insurers and Medicare HMOs is to require preauthorization for radiation treatment. This can be extraordinarily restrictive. Generally there are limitations on stereotactic radiosurgery as well as intensity-modulated radiation treatment. Often the patient will need to undergo simulation, and treatment can be delayed until a reviewer can decide if IMRT is warranted or three-dimensional (3D) conformal treatment will suffice. Needless to say, we do not get reimbursed for the treatment plans of both modalities, although they are requested by the insurer. There are various sets of guidelines developed by insurance companies to help their reviewers authorize or deny complex radiation oncology treatments. If denial occurs, again, it can be appealed, but the patient waits for treatment. Be sure to insist on a reviewer who is a board-certified radiation oncologist and not a retired general practitioner.

MEDICARE ADVANTAGE HEALTH MAINTENANCE ORGANIZATION INSURANCE PLANS

MEDICARE ADVANTAGE HEALTH MAINTENANCE ORGANIZATION INSURANCE PLANS

In 2007, Medicare Advantage Health Maintenance Insurance Programs were created. The insurance companies who administer Medicare HMOs are currently reimbursed up to 19%, more than traditional Medicare pays for each senior’s care.4,11 The seniors who sign up for Medicare Advantage plans often receive less care but pay higher copays and higher deductibles, and more than half of Medicare plans pay physicians below traditional Medicare rates. Many seniors do not realize that with a Medicare Advantage plan they need secondary insurance to pay for the additional costs that Medicare Advantage does not cover. More than 2,000 physicians responding to an American Medical Association survey on Medicare HMOs noted that Medicare HMOs routinely denied services typically covered by traditional Medicare plans including colonoscopies, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood tests, and other cancer screening procedures. A survey of patients enrolled in Medicare Advantage HMOs reported that 80% of them did not understand their plans and 60% did not realize they were actually giving up traditional Medicare.11 Some seniors are being sold Medicare HMO plans through abusive marketing practices. CMS singled out insurers including United, Humana, Coventry, and Cigna for abusive marketing techniques, and these companies were advised to take steps to more closely scrutinize their sales personnel. Medicare Advantage plans have created an incentive for insurance companies who sponsor these plans to enroll healthy new patients. The bottom 50% of Medicare recipients spend only 3% of Medicare health dollars.11 Insurance companies have found ingenious ways to enroll healthy seniors while making enrollment inconvenient to patients with many chronic diseases who might cost more. These incentives include offering free gym memberships to those enrolled (this appeals to the healthiest, most ambulatory seniors) and holding dinner seminars for prospective enrollees after dark in locations without access to public transportation or that require ascending several sets of stairs. An investigation by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission in 2004 found that Medicare HMOs were designing their plans to avoid paying for kidney dialysis, chemotherapy drugs, home care, and radiation treatment. A New England Journal of Medicine article noted that currently enrolled Medicare HMO members spent only 66% of the average cost of non-Medicare HMO patients during the year prior to joining the HMO. This may indicate selection of the healthiest seniors. Seniors departing from Medicare HMOs went on to spend 180% of this average, indicating that sicker patients were leaving Medicare HMOs possibly due to higher out-of-pocket costs. Cancer treatment, unfortunately, continues to be extraordinarily expensive. We must keep informed as to where cost shifting is going in the future and educate our seniors.11

PATIENTS REQUIRING RADIATION TREATMENT WHO RESIDE IN SKILLED NURSING FACILITIES

PATIENTS REQUIRING RADIATION TREATMENT WHO RESIDE IN SKILLED NURSING FACILITIES

Skilled nursing facilities are paid for by Medicare for seniors who need more care than a nursing home can provide but less care than an acute hospital provides. The skilled nursing facility is reimbursed by Medicare at a fixed rate per day for a patient’s care. When patients residing in a skilled nursing facility require radiation treatment, if the radiation facility bills under Medicare Part B (physician and outpatient services), the skilled nursing facility is responsible for reimbursing the radiation oncology facility and physician out of the fixed amount of money that is received each day by the facility. Conversely, if a radiation facility is owned by a hospital and bills under Medicare Part A, a separate payment by Medicare Part A is made to the radiation oncology facility and thus does not cost the skilled nursing facility any portion of their daily fee. Because of this, there is a financial incentive to refer or divert patients who need radiation treatment to a hospital-based facility billing under Medicare Part A. Of course, skilled nursing facilities do not wish to generate a bill that would require payment by them for referring patients to a Medicare Part B facility. This places outpatient facilities at a distinct disadvantage and is certainly unfair. The radiation oncology community is lobbying to change this practice.

RADIATION TREATMENT OF PATIENTS ENROLLED IN HOSPICE

RADIATION TREATMENT OF PATIENTS ENROLLED IN HOSPICE

It is not unusual for patients in hospice care to require palliative radiation treatment for pain control, palliation of neurologic symptoms, and so forth. Under Medicare Part B, the outpatient facility can directly bill Medicare with a GV modifier. The GV modifier indicates that the radiation oncology facility is separate from hospice and that the physician who is consulting and overseeing radiation oncology care is not directly employed by the hospice facility. Hospice benefits do include radiation treatment if this is included in the hospice plan of care. Thus, if the hospice facility includes radiation treatment in its plan of care for a patient, it must pay for it out of its daily reimbursement, a fixed amount per day. Currently hospice services are paid for by Medicare with a daily fee. This is paid 7 days a week for a maximum of 6 months. However, hospices usually only provide care 1 to 3 days per week. Hospices are among the few patient care providers that receive reimbursement from Medicare, depend on volunteer services to provide some of the care, and receive charitable donations from the public. Consider this when donating your time or money to a for-profit or not-for-profit hospice.

MEDICAL PHYSICISTS: SHOULD THEY BILL MEDICARE DIRECTLY FOR THEIR SERVICES?

MEDICAL PHYSICISTS: SHOULD THEY BILL MEDICARE DIRECTLY FOR THEIR SERVICES?

Many medical physicists maintain that they are board-certified professionals so should be able to bill Medicare directly; however, if they did so, their paychecks would shrink considerably. In 1960, lists of providers who could bill Medicare directly were formulated, and physicists were not among these professionals. Because of this, a congressional act is required to give billing status to medical physicists.12 Currently there are only two codes recognized for the contribution of medical physicists: code 77336, continuing medical physicist services, and code 77370, special medical physics consultation. There are no other CPT codes in Medicare Part A or Part B that identify any medical physicist component of work.12 At Florida Medicare rates, code 77336 is reimbursed at $50.43, and code 77370 is reimbursed at $105.55. In a busy department with 30 patients under continuous radiation treatment, there would be 30 continuing medical physicist services provided at a Medicare reimbursement level of $50.93 for 50 weeks per year, for a total reimbursement of $75,645. If 50% (this is high) of patients under treatment required a special medical consultation, this would mean a yearly reimbursement of $15,833. The total for these services, $91,478, is dramatically below what the average medical physicist makes in the United States.12 In 2007, CPT code 77336 was submitted to CMS 475,000 times at a reimbursement of $50.93. This would yield total reimbursement for medical physicists of $24,191,750. During the same year, CPT code 77370 was submitted 25,000 times at a reimbursement of $105.55 for a total Medicare payment of $2,638,750. When we combine these two numbers we get a total reimbursement for physicist services of $26,593,000. There are currently 4,700 members of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine. It is uncertain as to how many medical physicists practice exclusively in radiation oncology; most estimate approximately 25% of the total. If we use the number of 1,000 medical physicists in the United States splitting the total reimbursement for physicist services delivered to Medicare patients in the United States, we get a per physicist rate of $26,593. Again, this is rather dramatically below what the average medical physicist makes in the United States. Professional self-determination appears to be important to medical physicists. If we examine published literature available to the public on the process of radiation treatment, very little mention is made to medical physicists being members of the patient care team. This is true of the National Cancer Institute’s manual on radiation therapy and the American Cancer Society’s publication on the process of care for radiation oncology. This is unfortunate. There is certainly room for improvement to include medical physicists in the process of care because they are an integral component. The patient should understand their role, and perhaps additional efforts can be directed toward recognizing the contributions of medical physicists in the care of our cancer patients.12

RADIATION ONCOLOGY NEGOTIATION WITH MANAGED CARE PLANS

RADIATION ONCOLOGY NEGOTIATION WITH MANAGED CARE PLANS

In 1937, Dr. Sidney Garfield provided prepaid medical care for Henry J. Kiser’s company in California, and this was the beginning of managed care in the United States. Managed care proliferated with the objective to reduce health care costs for workers covered by health care plans paid for by their employers.4,10

Many physicians have experience negotiating the rate of compensation for their contracts. However, a managed care company may be reluctant to disclose their fee schedule if other physicians in the area are contracted with them. Begin the negotiation by making an inquiry for 10 codes most commonly used for radiation oncology patients. Oftentimes, a managed care company will send the reimbursement for 10 codes total. From this it is possible to get an idea as to what the company’s rate of payment is and whether you wish to continue the negotiation.4,10

Many private insurance contracts try to link reimbursement to a percentage of Medicare rates. Some managed care plans pay you based on 100% of the regional managed care company’s usual and customary fees. Often, this is below Medicare rates, and it is imperative to know exactly how you are being paid.4,10 Many managed care companies want you to take a fee reduction across the board for all radiation oncology CPT codes. Try to negotiate reduction in only a few codes (used less often), which may have a less deleterious effect on your practice. Always attach a comprehensive fee schedule to all contracts and make the insurance company sign off on this as an exhibit. This clearly prevents confusion later and locks in your rate of reimbursement instead of having it adjusted each year depending on Medicare rates.

Some managed care companies will try to get you to contract for a case-rate structure. In this scenario, for any patient who requires radiation treatment, a fixed dollar amount would be paid regardless of treatment complexity. Case-rate arrangements can sometimes be tiered, which allows two to three levels of complexity paid at a fixed rate. Case-rate reimbursements are difficult to manage and frequently do not increase year to year, while the complexity of treatment does increase. The physician is advised to use caution in accepting any case-rate structure.10

There are a few managed care companies that reimburse based on a capitation basis. Under this scenario, a certain amount of money is paid monthly to the radiation oncology group to provide services regardless of the covered population’s average age or need for radiation treatment. These contracts are extraordinarily difficult to negotiate and manage. Ultimately, to remain solvent, you would need to know the age of the population insured, as well as their cancer incidence, cancer screening availability, and so forth. Unfortunately, this information usually resides with the insurer, and most likely they will not share this with the physician. Capitation rates can also be calculated from population-based data using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data.4 Nonetheless, these data underestimate the incidence of cancer and the volume of cancer treated with radiation.

For hospital-based practices, it may be necessary for the managed care company to have a contract with the hospital for the technical component of radiation treatment and a contract with the radiation oncologist for professional services. Pitfalls to watch out for include a provision that the codes with a professional/technical split must be billed on the same day by both the hospital and physician for either to obtain payment. This puts the physician in the position of auditing the hospital charge capture, a notoriously inefficient process.4

A contract with the managed care company should spell out emergency care provisions. Many times emergency treatment for spinal cord compression or brain metastasis, for example, will be provided and a managed care company will later indicate that this was a noncovered service, even on an emergency basis. Thus, an entire course of treatment may be denied in this way.10

The managed care organization may wish to retain the right to reduce current reimbursement to you for prior payments that were paid in error. Thus, they may “set off” current payments by past debts. Some states laws do not allow this. These clauses are often subject to abuse. For example, suddenly the managed care company decides that dose calculations (code 77300) are “bundled” or included in special medical physics consults (code 77370). They will be able to potentially audit the practices to disallow as many 77300 codes as you have and adjust the billing to create a debt for 3 years’ worth of 77300 charges against which future payments are applied.

Audit provisions are similarly important to negotiate. Provisions on closing the claims process should apply equally to physician and managed care organizations. The time limit for auditing should be similar in time to which forfeiture of payment occurs. For example, if the managed care organization allows submission of bills up to 12 months after a service is rendered, you should negotiate an audit provision for only 12 months. Longer audit provisions may lead to abuse. Large-scale insurance companies routinely hire an auditing company on a contingency basis that is motivated to audit claims and recover payments. Occasionally audits are used to retaliate against physicians who request arbitration of unpaid claims.

It is important to assess your strengths and weaknesses during the negotiation process. Managed care companies realize that their contracts are subject to termination. Because of this, they usually do not depend on a single provider for medical care. Are you a second source of radioactive isotope therapy or radiopharmaceutical therapy? Are you one of only two providers of high–dose-rate brachytherapy in your area (which avoids a hospital stay)? Are you the only provider of intensity-modulated radiation treatment or the only practice that will treat children? All of these things count as strengths in negotiations and can be effective in setting the tone for negotiations with insurance companies.

SILENT PREFERRED PROVIDER ORGANIZATIONS

SILENT PREFERRED PROVIDER ORGANIZATIONS

Because of the rise of managed care, a new process has been promulgated whereby a network in which a physician is contracted as a preferred provider is sold to another health plan without the physician’s knowledge or consent.13 This creates a silent preferred provider organization (PPO) in which a discount is extracted from the physician’s usual and customary fees without the physician’s consent. The net result is a secondary discount where an insurer (often with a low number of patients) pays the physician’s discounted fee without the physician ever receiving the benefit of any additional patient volume. In most instances physicians become aware that they are victims of a silent PPO after providing services to a patient with indemnity insurance. When payment is made on behalf of an insurance company, the discount is applied even though the patient is not a member of the PPO and the physician is not a contracted member of that insurance organization. Unfortunately, there is no Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) statute governing selling lists of physicians and their associated contracted discounts. The American Medical Association estimates that $750 million to $3 billion is lost annually in the United States by physicians to silent PPOs.13,14 The American Medical Association was successful in banning silent PPOs from all federal employee health insurance benefits contracts. However, currently state insurance boards generally provide insurance regulations. A few states including North Carolina, Louisiana, Oklahoma, California, and Texas have passed legislation banning this practice.14 One simple step to combat this practice is to carefully read all contracts. Many health insurance contracts contain provisions that allow them to enter contracts with “other payers on the physician’s behalf.” If this language appears in your contract, insist on striking it. Additional language to protect yourself might include the prohibition of selling, renting, or leasing networks providing any information about a fee schedule to anyone without your express permission.13 Currently the only recourse after an inappropriate discount has been applied and you have been paid inappropriately is to use the legal system. As always, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” so be sure to look for the aforementioned clauses and lobby your state medical association to pass legislation that protects physician information.

ECONOMIC PROFILING: INSURANCE COMPANIES DETERMINE WHO PROVIDES THE LEAST EXPENSIVE CARE

ECONOMIC PROFILING: INSURANCE COMPANIES DETERMINE WHO PROVIDES THE LEAST EXPENSIVE CARE

Economic profiling tracks physician care expenditures including specialty referrals, laboratory testing, and utilization of other costly resources. Physicians are allowed to continue on the panel of certain insurance plans based on their level of utilization and cost to the insurance plan. Yet, expenditures to provide care to individual patients are variable.15 Patients who have complex cancers have a higher average cost of care, which may institute multiple inquiries from the insurance company about specialist referral, prescribing habits, and overall resource utilization. Higher average costs of care may lead to deselection from insurance plans for “outlier” utilization. When comprehensive care is provided in a single geographic setting, insurance companies know that patient compliance in the stated plan of disease management is enhanced, leading to fewer episodes of missed testing or treatment. This “dropout rate” is calculated as care prescribed by a physician but not undertaken by a patient.15 Physicians with high dropout rates reduce costs to the insurance company, but only temporarily.

ECONOMIC CREDENTIALING: HOSPITALS SEEK TO PREVENT PATIENT CHOICE

ECONOMIC CREDENTIALING: HOSPITALS SEEK TO PREVENT PATIENT CHOICE

Economic credentialing is defined by the American Medical Association as the “use of economic criteria unrelated to the quality of care or professional competency to determine an individual physician’s qualifications for granting or renewal of medical staff privileges.”16 The goal of economic credentialing in radiation oncology is to capture a revenue stream by denying hospital privileges to a group or terminating hospital privileges and thereby limiting competition. Hospital bylaws are considered by many states to be a contract between a hospital and medical staff, serving as a guideline for actions against physicians, as well as outlining due process provisions for physicians.16 Read your hospital bylaws carefully and watch for hospital proposed changes. The medical staff should have its own legal representation, separate from the hospital, when hospital bylaws changes are proposed.

Hospitals may seek to institute differential credentialing to keep qualified physicians from becoming members of the medical staff, and thus limiting competition. One example is requiring radiation oncologists to complete 4 years of residency, whereas before 1994 radiation oncology residencies were only 3 years.16

Contracts between physician groups and hospitals establish a business relationship to provide radiation oncology services. Traditionally, exclusive contracts ensured patient access to care that would otherwise not be available. Because of increased access to cancer treatment in the United States, this is almost never the case today. Most hospitals enter into an exclusive contract strictly for financial reasons, which puts the physicians in the position of being controlled by the hospital master financial plan. Exclusive contracts may deprive patients of choices and limit the establishment of new physician practices. Some exclusive contracts contain “clean sweep” provisions, which stipulate that when a group loses an exclusive contract with a hospital, each physician simultaneously forfeits clinical privileges without the benefit of due process afforded by the hospital bylaws.16

The peer review process may be misused to further a hospital’s economic goals. Because in most states peer review proceedings are protected from legal discovery, peer review affords an opportunity for physicians to evaluate their care and remediate their knowledge if necessary. Protection from legal discovery also invites hospitals to target and eliminate physicians who are economic threats to their service lines. This is particularly true for hospital-based specialists including radiation oncologists. Some radiation oncologists find themselves excluded from equipment or facilities when a health care institution changes radiation oncology from a hospital inpatient service to an outpatient service. This may occur with no change in location of building, equipment, or staffing. There is an entire consulting industry that teaches hospitals how to displace existing radiation oncologists and put their replacement physicians on salary. We are not the only target; physical medicine, diagnostic radiology, and cardiothoracic surgery are also vulnerable to these tactics.16

The American Medical Association has a long, continuous interest in fighting economic credentialing and has a litigation department with years of accumulated information and experience and will assist physicians who challenge health care institutions about these issues.16

RADIATION ONCOLOGY’S SOCIOECONOMIC TIES WITH DIAGNOSTIC RADIOLOGY

RADIATION ONCOLOGY’S SOCIOECONOMIC TIES WITH DIAGNOSTIC RADIOLOGY

In previous years, delivery of radiation treatment was both crude and considerably simpler. “Therapeutic radiology” was a discipline of diagnostic radiology. As radiation treatment became more sophisticated and as megavoltage linear accelerators became available, it was clear that separate training was necessary for radiation oncologists to treat cancer patients. Eventually new CPT codes were created for radiation oncology and governmental payers began to recognize us as being separate from diagnostic radiology. Diagnostic radiologists seem to be embroiled in a campaign to close the “in-office ancillary exemption,” which allows nonradiologist physicians to perform imaging within their offices. Currently, obstetricians perform pregnancy-related ultrasounds, cardiologists perform cardiac catheterizations and nuclear cardiac procedures, and family physicians perform bone densitometry and plain films within their offices. With the advent of image-guided radiation treatment, positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) simulators, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) simulators for treatment planning, radiation oncologists continue to fight for the ability to image our patients for diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning related to cancer. Our objective should be to show CMS that imaging is necessary for treating cancer patients appropriately.

In 2009, Medicare proposed a 95% “usage rate” for diagnostic imaging equipment and then proposed extending this to all medical equipment costing more than $1 million. This proposal was advanced by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and was based on a sample size of only six urban diagnostic radiology centers but, because of the cost of linear accelerators, was extended to radiation oncology.17 Data collected by U.S. Oncology show that 50% of linear accelerators installed in the United States operate at a 50% utilization rate or less.17 If this usage rate were enacted for radiation oncology, the technical reimbursement would be reduced with the assumption that more patients are being treated per day on each linear accelerator. A reduction in technical reimbursement would force the closure of many rural practices, making patients travel longer distances for cancer treatment. Fortunately, this proposal was defeated because radiation oncologists like you told Congress that we are different from diagnostic imaging. Radiation oncologists need to continue to show CMS that we treat cancer patients and are separate from diagnostic radiology.17

HEALTH CARE REFORM

HEALTH CARE REFORM

In 2011, 48.6 million Americans did not have health insurance. According to census data taken in 2007, approximately one-third of those uninsured held jobs that offered health insurance coverage and had salaries 300% above the poverty level. This group chose not to pay for health insurance due to cost considerations. The Affordable Care Act will enroll currently uninsured patients into the Medicaid program. This will be a payment windfall for hospitals, which would be paid for emergency room visits for which they now do not receive reimbursement. Private practice physicians may not see more Medicaid patients due to low reimbursement, thus encouraging the use of emergency rooms for primary care.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that tort reform with a $250,000 cap on noneconomic damages would save the United States $54 billion over 10 years and reduce national health care spending by 0.5% annually and save $41 billion in tests ordered due to physicians’ needs to practice defensive medicine.18 Medicaid expansion during a time when fewer doctors accept Medicare patients may not be an answer that is palatable to many physicians. The government has studied bundled “bulk” payments for hospital and physician care. One proposal would be to negotiate a bundled fee paid to hospitals for an episode of care (i.e., lung cancer). This led to the creation of accountable care organizations as part of the Affordable Care Act. The physicians would then negotiate with the hospital for their component of pay. As always, greater bargaining power is in the hands of the entity that receives the check.

ACCOUNTABLE CARE ORGANIZATIONS

ACCOUNTABLE CARE ORGANIZATIONS

Expenditures for health care in 2011 totaled $2.6 trillion. In the United States, we spend 17.6% of our gross domestic product on health care, which comes to $18,344 per person, while Japan spends 8.5% of its gross domestic product, accounting for $2,872 per person. Accountable care organizations (ACOs) promise to improve medical care coordination, with reductions in fragmented care, improvement in outcomes, and reductions in the cost of health care. Their successful operation is a priority in cost savings for the new Healthcare Reform Law. Under the Affordable Care Act, the minimum size of the population for Medicare beneficiaries for an ACO is 5,000 patients. ACO founders can be primary care physicians or independent practice associations. ACO participation includes hospital and physician specialists (like radiation oncologists). Patients are assigned to an ACO retrospectively. Thus, physicians providing care in an ACO do not know which patients do or do not belong to the ACO. Ostensibly, this is to encourage cost savings for all patients, not just those patients assigned to an ACO. Any savings achieved in the ACO population (actual medical care costs compared to expected medical care costs) are shared between Medicare and the ACO at a rate of 50%. If the cost of care for the population is more than 2% higher than Medicare expected, the ACO may need to repay this loss. Patients may self-refer to another Medicare provider physician outside their ACO, and care provided by that physician or that hospital counts against the ACO’s cost goals.

Because ACOs are controlled by primary care physicians whose missions are cost savings, this may not bode well for the specialty of radiation oncology. Most primary care physicians have a difficult time understanding the benefits of radiation treatment, especially in palliative cases as well as in cases where the cure rate is <50%. Primary care physicians may leave the decision for radiation treatment to medical oncologists. This decision making by medical oncologists may diminish once primary care physicians realize that delivering chemotherapy is by far the most expensive portion of cancer treatment with the extremely high cost of cancer drugs. It is possible that patients for whom palliation is a goal will automatically be enrolled in hospice. We may see more hip fractures, intractable pain from metastatic disease, and brain metastases go untreated, all with the goal of cost savings, which individually benefits Medicare and the physician partners in the ACO. Primary care physicians need to be educated as to the benefits of radiation treatment. We should let them know that treating a hip metastasis may actually prevent a total hip arthroplasty, which is a more costly event. Preventing or palliating a spinal cord compression might prevent paralysis and a prolonged episode of bedridden care. Radiation treatment is dramatically more cost-effective than Mohs microsurgery and reconstruction, which costs more than $1,000 per stage. This will be our mission for the future, and given the change in the health care landscape, this will be challenging.19

There has been a tremendous push for independent practice of nurse practitioners (without physician supervision) and for nurse anesthetists.20 The former may be provided to close the gap in primary care resulting from fewer primary care physicians choosing primary care as a profession due to low reimbursement.

The American Medical Association has requested insurance market reform with elimination of denials for pre-existing conditions, health insurance for all Americans, and health care decisions remaining in the hands of patients and their physicians, as well as repealing the Medicare sustainable growth formula that triggers deep cuts in Medicare and threatens seniors’ access to care. The American Medical Association also desires proven medical liability reforms to reduce the cost of defensive medicine.21,22

RADIATION ONCOLOGISTS’ LOBBYING AND POLITICAL ACTIVITY

RADIATION ONCOLOGISTS’ LOBBYING AND POLITICAL ACTIVITY

Americans place a high value on the quality and availability of medical care. In this country, we have massive government programs that provide the funds to pay for the health care of the poor, disabled, and elderly. Unfortunately, payment rules are created by the legislature for a large portion of all physicians’ practices in the United States.4,20 The importance of interfacing with governmental payers, as well as in influencing the process that benefits our patients and brings them new technologies, cannot be underestimated. This can be accomplished through membership and in financial support of organized medicine at all levels. Select the organizations that you support carefully and specifically with an eye toward those which provide lobbying power for you and for your patients.23–26 There are multiple organizations that interact with CMS. These include the American College of Radiation Oncology, the American Brachytherapy Society, the Association of Freestanding Radiation Oncology Centers, and the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology.23–27

STARTING A FREE-STANDING CANCER CENTER

STARTING A FREE-STANDING CANCER CENTER

Starting a free-standing cancer center requires substantial time, effort, and persistence. The population area served by the free-standing center must be clearly defined by the radiation oncologist. In an area where there is no cancer program, the population data for the area can be gathered, complete with the age range of the population and the number of each potential patient within defined age ranges. SEER data can then be applied using population-based cancer incidence. In 2010, the age-adjusted incidence of new cancers diagnosed was 5.4 cases per 1,000 men and 4.1 cases per 1,000 women.4,28,29 The raw cancer incidence provided by the SEER data does not tell us how many patients may undergo radiation treatment during the course of their illness. Take the number of estimated patients and then apply a yield ratio of approximately 50%, which should estimate the total number of patients that the new cancer center would serve. An additional 25% of patients will need to be retreated for other metastases or other new primary cancers.29 Model radiation oncology courses of treatment must be developed to estimate reimbursement per course of treatment (see Fig. 100.1).4 A certain percentage of patients will receive a palliative treatment course, 3D conformal treatment, and intensity-modulated radiation treatment. If an average length of treatment (including palliative treatment and definitive treatment) is approximately 5 weeks, to have 20 patients under continuous treatment per day will require 200 new patients per year.

A second way to estimate the population served is to count the number of occupied beds of hospitals serving the area. Each permanently filled hospital bed yields approximately one cancer patient per year, of which half will require radiation treatment.

For a cancer center in a competitive market, one must establish exactly how many patients would be treated in the new cancer center and specifically how the physicians plan to obtain these referrals. If a hospital-based group of physicians builds its own free-standing cancer center, some of the patients may follow because referring physicians will continue to refer. There are always surprises and changes in referral patterns when hospital-based radiation oncologists open a competing free-standing center.4

Once the numbers of patients to be treated are established, along with their treatment length, the reimbursement for an “average course of treatment” can then be calculated. This average course of treatment should take into account intensity-modulated radiation treatment, palliative treatments, and 3D conformal therapy. When one uses a conservative estimate and sets the total reimbursement at Medicare rates, this seems to be a reasonable approach to many lending institutions. Once total collections for the population to be served are established, the total expenses need to be established, as well. This includes the costs of debt service, interest, principle, sales tax on equipment when installed, electric bills, costs of physics and dosimetry, costs of personnel including nursing and therapists, costs of water, building maintenance, professional liability, building insurance, employee benefits, physics equipment, accelerator maintenance, and so forth.

All of this can be packaged together as a pro forma to take to your financial institution. Generally, banks require a down payment between 5% and 20% of the total amount borrowed. In addition, working capital will be needed for approximately 6 months of operation.4 The pro forma should be conservative. The goal should be to exceed the numbers that are projected, not just to meet them. This will give the bank a substantial amount of comfort as well. The carrying costs of maintaining a center, maintaining a competitive edge with equipment, and attracting and maintaining high-quality personnel are substantial. If you have never run a free-standing radiation center, you may substantially underestimate the costs of running one.4 If medical oncology is to be added, the costs of the monthly drug bill need to be calculated.

MARKETING A RADIATION ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

MARKETING A RADIATION ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Marketing for radiation oncology is directed toward the referring physician. Determine the physicians most likely to refer to you and make a list. Any physician can be a referring physician.4,29 I have received two referrals from psychiatrists who had cancer patients that were unhappy with their care, underscoring this premise.

Presenting patient cases at cancer conferences at your local hospitals is a time-honored and useful form of individual marketing for your practice.4,29 Nursing staff usually attend, and they can be a referral source. Radiation oncology images can be rewarding to present at tumor boards. Outlines of isodose plans and other imaging studies, MammoSite depictions, high–dose-rate brachytherapy plans, and so forth, form an image in referring physicians’ minds that medical oncologists cannot accomplish.29

Giving talks to civic organizations and cancer support groups is also beneficial but requires patience for the long term.4,29 Although I give multiple talks to groups, there has never been an instance where someone in the audience decided that he or she would change to me as a physician as the result of my presentation. Nonetheless, there have been multiple times when family members of new patients have said that they have heard me give a presentation. This underscored another physician’s referral choice.

Advertising to the public generally does not yield new patients on its own. Advertising advanced technology may be helpful but usually only bolsters the understanding and familiarity with your physicians and facility when another primary physician makes a referral. In some larger urban markets, advertising advanced technology may make a difference or get some patients to call, ask questions, and possibly self-refer.

If your hospital has a teaching program, it is often rewarding to give a lecture or two within this program.29 Physicians who attend will soon become your referring physicians, especially if they stay in the area to practice.

Develop a telephone answering on-hold message that showcases your technology, as well as the talents of your physicians. Thus, when the patients and physicians call, they are given an explanation of exactly what your practice does while they are waiting for the receptionist. Developing an immediate fax or e-mail form to briefly let referring physicians know what is being done for a new patient facilitates communication and gives them immediate information about the workup and progress of a patient you have seen.4

Internet website development can also be helpful. Again, this usually does not yield new patients, but rather reinforces the choice that other physicians have made to refer patients. Patients can find out about your practice on the Internet, as well as fill out their intake forms, and so forth. Some of these techniques may be helpful. But none of these techniques will be useful unless outstanding patient care is delivered, both socially and medically.

SELLING A FREE-STANDING CANCER CENTER

SELLING A FREE-STANDING CANCER CENTER

In recent years there has been much interest by private or publicly traded groups in purchasing radiation oncology centers. Publicly held or private corporations may seek to purchase radiation oncology centers to induce an economy of scale, dominate a certain region or state (and thereby exact additional reimbursement from the area insurers), or ultimately go public (issue stock certificates that can be purchased by the public). Generally a sale is based on earnings before depreciation, interest, taxes, and amortization (EBDITA). A multiple of this number is paid to the owner, generally in the 4 to 7.5 range. This range will decrease as cuts in reimbursement occur. Generally purchasers ask the owner to retain a minority percentage of the original cancer center he or she built. Sometimes this can be as small as a few percent, sometimes up to 49%. The purchasing entity may propose an automatic payout for the final percentage after 2 to 5 years of employment. It is important to negotiate how the buyout will be valued into the future. One potential problem is that an entity that owns more than 50% of your cancer center may dramatically reduce the profitability of this facility by allocating expenses incurred in the home office to your office, which actually is treating patients. This reduction in profitability likely will affect the buyout price in the end and will not adjust it upward. Sellers of radiation oncology practices should be aware of this potential and retain as small a percentage as possible or none at all. Some purchasers require a reduction in the ultimate purchase price based on the prospect of reduced reimbursement for some procedures. For example, an IMRT or stereotactic radiosurgery “earn-out” may be a reduction in payment price based on the future of reimbursement for these two modalities, with a portion of the purchase price paid at a later date. Predicting into the future of reimbursement is beyond the scope of most of our readers.

NONPROFIT HOSPITALS AND RADIATION ONCOLOGISTS

NONPROFIT HOSPITALS AND RADIATION ONCOLOGISTS

Earnings from many nonprofit hospitals have soared, with a combined income of the 50 largest nonprofit hospitals in the United States increasing eightfold to $4.27 billion between 2001 and 2006, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis updated from the American Hospital Directory. Nonprofit hospitals’ “excess cash flow” (we call this profit in the for-profit sector) is spent on new facilities, generous executive pay, and often new and lavish cancer centers.30 The largest nonprofit hospital chief executive officer pay ranged from $3.3 million to $16.4 million per year.30 Historically, most nonprofit hospitals in America have been recognized as charitable organizations and exempt from taxes under Section 501(C)3 of the U.S. tax code. In return for a generous tax exemption, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) previously required nonprofit hospitals to provide a substantial amount of charity care for the poor. However, in 1965, when Medicare and Medicaid were created, the hospital industry felt there would not be enough demand for charity care to satisfy the IRS exemption standards. With substantial lobbying, the nonprofit hospital industry pushed for more flexible exemption that became known as the Community Benefits Standard adopted by the IRS in 1969. This allowed hospitals to provide local “community benefit” consistent with any other nonprofit hospital in their area.30 Unlike for-profit hospitals, nonprofit hospitals do not pay dividends to shareholders. Instead, they use “excess cash flow” (profits), earned from operations, to pay for new facilities. Among these are proton treatment centers under construction in the Midwest, and located within minutes of each other, and various cancer centers being built by nonprofit hospitals without paying any taxes. These compete with those facilities that do pay taxes. While nonprofit hospitals have a charity obligation to the communities they serve, do they compete with physician practices by using an unfair tax advantage?

FEDERAL STARK REGULATIONS AFFECTING RADIATION ONCOLOGY

FEDERAL STARK REGULATIONS AFFECTING RADIATION ONCOLOGY

Current Stark laws prohibit self-referral to designated health services, which includes radiation oncology. Radiation oncologists who own their own facilities and equipment do not fall under violations of the Stark rule because it is not considered self-referral when the referring physician personally performs a designated health service in his or her own facility.31

There is also an in-office ancillary exemption, which applies to ownership and investment interest for ancillary services. The in-office ancillary service must be provided in a building in which the referring physician also furnishes substantial physician services.31 This loophole has been exploited by some urologists to create a “group practice” with radiation oncologists and add a linear accelerator to their building. Curiously enough, the very radiation oncologists who join these ventures are often the displaced victims of hospital tactics of economic credentialing (see next section).

Congress made some of its conclusions and wrote portions of the Stark law based on studies that examined the effects of ownership of free-standing radiation oncology facilities by referring physicians who were not radiation oncologists and did not directly provide services. These “joint ventures” yielded a utilization rate 40% higher in these facilities than the rest of the United States, and a cost of radiation treatment that was 60% higher than the rest of the United States.32 In addition, these studies showed that there was less access to poorly served populations without any reduction in mortality among cancer patients that indicated improved quality of care.31,32 State laws may strengthen current existing federal laws, and it is important to understand the laws in your state concerning self-referral.4,31,32

“GROUP PRACTICES” INCLUDING RADIATION ONCOLOGY, UROLOGY, AND OTHER SPECIALTIES

“GROUP PRACTICES” INCLUDING RADIATION ONCOLOGY, UROLOGY, AND OTHER SPECIALTIES

Radiation oncologists have become increasingly concerned about the growing trend of self-referral for radiation treatment services by other specialty physicians seeking to create a group practice for apparent economic gain. Physician-driven financial arrangements may be consummated specifically to facilitate the delivery of intensity-modulated radiation treatment and have caused concern for the quality and cost of radiation treatment delivery. These arrangements have caused proliferation of “multispecialty groups” with the objective of delivering IMRT to prostate cancer patients that the group’s urologist diagnoses. Prior to the initiation of the Stark laws, studies of radiation oncology facilities owned by referring physicians reported higher costs for cancer treatment without improved outcomes.33 Radiation oncology is a designated health service under Section 1877 of the Social Security Act, which prohibits financial arrangements between the physicians and entities providing these services. Congress created an “in-office ancillary exemption” to protect medical services for which a service or test result is immediately needed for in-office patient care. As part of a program to address and study this growing trend, the American College of Radiation Oncology (ACRO) issued a physician statement on self-referrals specifically addressing the formation of urology and radiation oncology radiation groups for apparent financial reasons. ACRO then surveyed radiation oncologists who identified themselves as having a financial relationship with urologists. After telephone verification, there were 75 radiation oncologists who identified themselves as having a practice model that included urologists. The radiation oncologists were both employed in and a financial partner in the group. No radiation oncologists responded that their practice model included “block leasing” linear accelerator time to urologists. For all respondents, the radiation oncologists received the professional component of treatment. All 75 respondents either were economically displaced in a geographic region by an existing radiation oncology group or were economically displaced by a hospital in their region.33 All respondents were unable to achieve professional partnership status within a radiation oncology group, and 98.6% were unable to achieve any share of the technical component for radiation treatment within a radiation oncology group.

Sixty-six of 75 physicians provided a daily total of prostate cancer patients treated in their facility.29 The range was one prostate cancer patient treated per day (newly started practice) to 48 patients per day (mature practice).33 The mean was 17.1 prostate cancer patients treated per day. Eighty-six percent of radiation oncologists within this model were treating both prostate and nonprostate cancer patients. The average combined urology–radiation oncology practice treated 33 patients per day with nonprostate malignancies. Thus, the radiation oncologists responding to our survey who treated both prostate and nonprostate cancer patients treated 1.9 times more nonprostate cancer patients than prostate cancer patients.33 This may possibly indicate that urologists seek radiation oncologists in an area where radiation oncologists already have an established referral base and bring nonprostate cancer referrals with them.33 On August 19, 2008, the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) issued an opinion on the relationships between urologists and radiation oncologists that addressed leasing radiation equipment to provide IMRT to prostate cancer patients that urologists diagnose. The OIG expressed concern that urology groups are in a position to choose IMRT instead of other forms of radiation and ensure economic success of a joint venture while assuming minimal business risk. The radiation oncologist would then be able to reward the referring urologist with a profit. The opinion as written states, “We conclude the proposed arrangement could potentially generate prohibited remuneration under the anti-kickback statute.”33 Unfortunately, this opinion applies to equipment leasing arrangements only.

Some hospital medical oncologists, general surgeons, and neurosurgeons also choose a variation of this business model when they combine with radiation oncologists to provide radiation treatment including robotic radiosurgery.33 Again, the radiation oncologist is in a position to reward the owners of equipment with a profit.

ECONOMIC ISSUES SPECIFIC TO NEW GRADUATES OF RESIDENCY PROGRAMS

ECONOMIC ISSUES SPECIFIC TO NEW GRADUATES OF RESIDENCY PROGRAMS

Most new graduates are largely concerned about mastering the amount of medical knowledge necessary to become a specialist, as well as passing their radiation oncology boards. Few articles have been written on contracting specific to radiation oncology.34 A contract is a promise between two parties that the law recognizes as a duty. Five elements are required to create a valid contract: two competent parties, mutual consent, consideration, a legal purpose and duty, and a mutual obligation. When evaluating a first contract, obtaining legal advice from a health care attorney is essential.

The terms and conditions of the contract should set forth working conditions, provision of nursing service, transcription, ancillary help, on-call arrangements, vacation time, and coverage. Arrangements should be spelled out for professional liability insurance coverage including term limits and a tail policy in the event that termination of employment occurs. Duties should be specific to the practice of radiation oncology and not be vaguely worded so the new physician is expected to “perform all duties as the board of directors may assign.”34 The employer should also spell out the terms of potential termination. Reasonable terms of automatic contract termination include loss of your medical license, loss of hospital privileges for patient care issues, loss of a drug enforcement agency license, loss of ability to prescribe controlled substances, conviction of a felony, and so forth. If there is a provision for termination of the contract prior to the end of the term, it should be clear and available to both parties. For example, “either party may terminate this agreement with 90 days written notice with or without cause.”34 Written performance reviews should be given at least quarterly. This assists the employer and the employee to identify potential areas of conflict and allow resolution.

Restrictive covenants protect employers by placing limitations on the rights of the employee to compete with the employer. They should include the period of time the restriction shall remain in effect, as well as the geographic restriction. Because some of these restrictive covenants are not enforceable in certain states, liquidated damages for terminating employment and remaining in an area to compete has also been used by some practices.34 A liquidated damage clause provides a payment to the practice owner, negotiated in advance, that allows the employed physician to work in the area and compete after the contract is terminated.34

Associates are invited to become partners after some period of time, which varies from region to region. Traditionally, this has meant financial parody with the senior partners. Many physicians are being offered positions without a partnership track. Partnership has also traditionally meant voting and decision-making parody. Some groups offer graduated financial parody: the first 2 years may be salaried, and during the next 3 years they may gradually reach financial parody with senior partners in percentage increments. Formulas for buying into the practice are similarly variegated. In a hospital-based practice with an exclusive contract to provide professional services, the buy-in should be minimal, simply because the cost of maintaining the contract is minimal. There is no cost to maintain equipment. One should only purchase assets that have real value or cover the cost of maintaining the contract over time. The accounts receivable are usually generated by the physician during the years of nonpartnership. One questions a “buy-in” for these accounts receivable that the new physician helped to generate. Good will is augmented by the employed physician, who builds and contributes to practice expansion during the nonpartnership years. It is my opinion that accumulated practice goodwill is not worth a great deal financially.

Less than one-third of radiation oncologists are still in their first postresidency job 5 years later.4,34 If negotiated into the contract, arbitration or mediation can be an effective and cost-efficient means to negotiate a dispute and avoid litigation between parties, should you decide to separate.4,34

ECONOMICS OF MEDICAL ONCOLOGY

ECONOMICS OF MEDICAL ONCOLOGY

As a way to achieve prescription drug coverage for our seniors, chemotherapy drug payments became the source of some revenue.35 The target is huge: Medicare spends $70 billion each year for chemotherapy drugs. Compare that to the amount spent on radiation oncology professional and technical fees, which totals $7 billion per year, and our services appear very cost-effective.35,36 Outpatient drug reimbursement has changed from paying a percentage of the average wholesale price (AWP) to paying a percentage of the average sales price (ASP). ASP is the sales price that is actually paid by outpatient practices with a tiny margin added, only 6%. Medical oncologists argue appropriately that the administration of chemotherapy does not cover the cost of nursing time, waste disposal, and supplies. Medicare responded to this reality by increasing the fee for administration of the first hour of chemotherapy infusion by over 270% between 2003 and 2004.36 Because reimbursement for the first hour of chemotherapy has had the most dramatic increase in reimbursement for medical oncology, this makes any regimen that requires multiple days of therapy profitable for our medical oncology colleagues. These include daily or weekly chemoradiation protocols.36 There is a new drug reimbursement update by Medicare every 12 weeks as the average sales price for chemotherapeutic drugs is recalculated by CMS. There continue to be proposals to reimburse chemotherapy drugs by Medicare at ASP plus 3%—a 50% cut in profit margin.

Consulting groups are letting medical oncologists know that they can profit from incorporating PET scanners, CT scanners, and radiation oncology equipment into their practices. Perhaps more realistically, medical oncologists will be looking for reduction in their overhead through combining with radiation oncologists and being able to enhance patient care by giving daily chemotherapy sensitization protocols within a combined cancer center. Do not build a new cancer center without at least considering adding space for medical oncologists.

MEDICAL ONCOLOGY SUPPLY AND DEMAND: HOW WILL THIS AFFECT RADIATION ONCOLOGY IN THE FUTURE?

MEDICAL ONCOLOGY SUPPLY AND DEMAND: HOW WILL THIS AFFECT RADIATION ONCOLOGY IN THE FUTURE?

The demand for medical oncologists will rise by 48% in the year 2020, but the supply will only rise 14%, creating a 34% shortfall in the number of medical oncologists needed in the workforce. These conclusions were drawn from a study performed by the American Association of Medical Colleges and reported in the Journal of Oncology Practice.37,38 The number of patient visits for medical oncology was determined by the National Cancer Institute analysis of the SEER database. There was no adjustment for the ever-lengthening regimens of palliative or adjuvant chemotherapy, nor was there any adjustment for patients with metastatic cancer who may live longer as a result of palliative treatment and thus require increased patient visits in the future. In his article, Dr. Erickson Salsberg proposes increased use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants and delays in retirement for current medical oncologists. He also proposes increase use of primary care physicians to monitor patients during and after chemotherapy.37,38 With the shortage of primary care doctors in the United States, this does not seem likely. One of our most respected mentors and long-time leader in radiation oncology, Dr. Luther Brady, teaches residents that we are first and foremost cancer physicians who use radiation as a tool to treat cancer patients. Radiation oncologists are trained in all aspects of solid tumor oncology and can easily direct medical care for cancer patients during their disease process. Given the need, there is every reason for radiation oncologists to see cancer patients for consultation and to design a program for biopsy, workup, and management of their malignancy, even if it does not include delivery of radiation treatment. We encourage radiation oncologists to step up to the plate and provide more consultative services, more direct patient care, more inpatient care, and more general oversight than ever before. This new role may be one of the most important challenges for our specialty. However, if realized, it will benefit countless cancer patients by the year 2020.38

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

PAY FOR PERFORMANCE

CMS continues to move toward pay for performance. Under this system, a physician practice meeting a certain benchmark of quality in patient care does not receive a reduction in Medicare payments. This movement, in its various combinations and permutations, including ACOs, started in 1999 when the Institute of Medicine released a report called To Err Is Human.39 This report documented quality-of-care concerns in our health care system and pointed out that 98,000 people die each year due to preventable medical errors from health care professionals. Subsequently, a Rand study found that many hospital deaths were preventable.40 In our legislators’ minds, the findings of these studies sharpened their resolve to improve the quality of care delivered in our health care system. Pay for performance has the objective of improving the quality of care by linking physician reimbursement to quality measures and outcomes. Pay for performance was first instituted in hospitals. Under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, hospitals receive a 2% reduction if they do not report to CMS on 10 quality measures and have acceptable performance targets. This pilot project with hospitals has been viewed by Congress to be successful. The results of quality-of-care measures for these areas are available on the CMS website for any hospital that participates.

Certain specialties lend themselves better to pay-for-performance measures than others. For example, diabetic patients should have retina exams as a component part of their care, and not doing so would not be optimal care for them. The care of cancer patients is, however, quite variegated. As we all know, some patients with brain metastasis live only a few months, and others live for a year or more. Thus, outcome measures for patients who have cancer would probably not be appropriate. It is the physicians themselves within each specialty that should shape the compliance program linked to pay for performance. In this regard, likely the better measure of quality of care would be accreditation of radiation oncology practices. This has not been adopted by CMS to date but is currently required in several states in the United States.41,42

RADIATION ONCOLOGY DEPARTMENT: APPROPRIATE STAFFING AND PERSONNEL

RADIATION ONCOLOGY DEPARTMENT: APPROPRIATE STAFFING AND PERSONNEL

Radiation treatment consists of a series of steps and involves a number of different professionals. Each radiation oncology department should establish a staffing program consistent with the level of patient care complexity and other factors within that department. Radiation oncologists can manage 30 to 40 patients per day under continuous radiation treatment. When considering new patient visits and simulation follow-up visits, this translates to 65 to 90 patient encounters per week and allows us sufficient time for treatment planning and clinical functions.43 Medical physicists should be available when necessary for consultation with the radiation oncologists and to provide advice and direction of the technical staff when treatments are being planned or patient treatment initiated. Chart checks by the physicists should be performed at least once per week. Generally one medical physicist is needed for every 30 to 40 patients under continuous radiation treatment.43 Medical dosimetrists act under the supervision of the radiation oncologist and medical physicist. There should be one full-time-equivalent dosimetrist per 40 patients under continuous treatment. More dosimetrists may be needed if a larger proportion of patients receive higher-complexity care. Radiation therapy technologists practice under the direction of the radiation oncologists. They should have achieved American Registered Radiologic Technologist (ARRT) certification in radiation oncology.43,44 One radiation therapist is needed for 20 patients under continuous treatment.43,44 It is ideal to have two therapists per treatment machine and to allow for vacations, meetings, absences, and so forth. Radiation oncology support staff may include radiation therapist treatment aides, who work under the direct supervision of the radiation therapist and radiation oncologist and are generally trained on site to assist and facilitate patient transport and patient flow.

RADIATION ONCOLOGY STAFF RECRUITING AND RETENTION

RADIATION ONCOLOGY STAFF RECRUITING AND RETENTION

In the United States, currently there is a critical manpower shortage in radiation therapy personnel. Regional shortage of therapists, dosimetrists, and physicists creates a “musical chairs” job market: the bell rings and everyone changes position.4 This situation is neither beneficial to patient care nor fiscally sound for our shrinking health care dollar. For those of us who have depended on temporary workers, we know that this is both an expensive proposition and seriously disruptive to employee morale.44

The U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics predicted that by the year 2010, there would be a shortage of 7,000 radiation therapists.4,44,45 A shortage of this magnitude did not seem to materialize. One way to stabilize your workforce, create good will, and create excellence in our field is to start a scholarship program for radiation therapy professionals. Currently, most scholarship programs support radiographers to take 1 additional year of training to become radiation therapists. During the time of training, the student can receive a stipend, as well as have his or her tuition and books paid for. In exchange, the candidate agrees to work for the cancer center for a period of years after graduation. One source of candidates can be a local radiography training program. Contact the director of the program and let him or her know that you are offering a scholarship program to qualified candidates. For students who receive monthly stipend support, the best way to ensure that they are serious about accepting the obligation is to have them sign a promissory note. If they fail to honor their contract or pass the registry within a specified period of time, the amount that the practice advanced them becomes immediately due with interest.4,44

Although many dosimetrists today are trained “on the job,” there are 1-year programs that enroll therapists in full-time dosimetry training. If you have a candidate willing to relocate to one of the cities that has these programs, it is worth the investment to train them outside of your facility and hopefully bring back some fresh ideas. For a radiation therapist who may have a baccalaureate degree in radiation therapy, and for the right individual who wishes to train in medical physics, this may be an opportunity to train a medical physicist for your program.

Opening your practice to scholarship programs and scholarship support creates a unique marketing opportunity for your facilities.4,44 This also augments cancer center morale, where the seasoned employees can teach the new graduates the tricks of the trade.4,44

PRACTICE ACCREDITATION

PRACTICE ACCREDITATION

Practice accreditation is a way to demonstrate the quality of radiation oncology practice to the public, as well as third-party payers. Practice accreditation may be one avenue whereby a practice demonstrates quality and distinguishes itself. Currently, ACRO and the American College of Radiology (ACR) are the two practice accreditation bodies for radiation oncology practices. Some states (Alabama, New Jersey, and New York) require practice accreditation for state certification.4,41,45

Most importantly, practice accreditation constitutes a mechanism to accomplish quality assurance and assess compliance with recognized standards for hospital or free-standing radiation oncology practices.4,41,45 Practice accreditation can also be a value-added qualification for third-party payers; some will require it in the future.

Standards for accreditation should include external review of randomly selected radiation oncology treatment courses, peer review, and quality assurance activities performed regularly; physics and dosimetry standards consistent with drafted standards for external-beam radiation treatment and brachytherapy; and medical physics quality assurance.41,42,45 An on-site verification visit by both physicists and physicians is essential to practice accreditation.45

ECONOMICS OF RADIATION ONCOLOGY: SELECTED INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

ECONOMICS OF RADIATION ONCOLOGY: SELECTED INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES