Early and Advanced Gastric Carcinomas

Shinichi Ban

INTRODUCTION

If untreated, gastric adenocarcinomas, which develop first in the epithelial component of the mucosa, will infiltrate the deeper layers of the gastric wall. The level of infiltration is important, since it influences prognosis, and the layers of the gastric wall are used as landmarks to define the T factor of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM-staging system of gastric carcinoma.1 However, it is only in the last several decades, with advances in radiologic and endoscopic diagnostic modalities, that an increasing number of early stage gastric carcinomas (pT1) have been detected, a shift that has prompted a division of gastric carcinomas into two groups, early and advanced, on the basis of the depth of invasion of the gastric wall. This division is convenient because the two categories differ in not only prognosis but also morphology and various clinicopathological aspects. Consequently, the recognition of these differences, in which pathologists have played a significant role, has contributed to the increasing improvement in the early detection and treatment of gastric carcinomas. Given this background, this chapter reviews various aspects of early and advanced gastric carcinomas, including their macroscopic appearances, the progression patterns from early to advanced stage, histologic characteristics, and prognostic relevance.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIVE INCIDENCE OF EARLY AND ADVANCED GASTRIC CARCINOMA

Early gastric carcinoma has been defined as any invasive adenocarcinoma confined to either the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of the presence of lymph node metastases.2 Importantly, the term “early” does not necessarily refer to the size or age of the lesion.3 Conversely, gastric adenocarcinomas infiltrating into the muscularis propria or beyond are termed advanced gastric carcinoma.2 The concept of early gastric carcinoma was first established in Japan in 1962 by the (now defunct) Japanese Endoscopic Society (currently the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society), which included endoscopists, surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists. The defining concept was that this group of gastric carcinomas could be successfully treated by surgery.4 It since has been confirmed that gastric carcinomas limited to the mucosa and submucosa generally have an excellent prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 90%.5,6 In contrast, the 5-year survival rate of advanced gastric carcinomas is around 60% or lower.7

Early and advanced gastric carcinomas differ in not only their prognosis but various biologic characteristics as well, which guarantee the validity of separately defining early and advanced gastric carcinomas. One difference is in the growth rate of these neoplasms. Although the infiltration of the gastric wall by neoplastic cells morphologically appears to be a continuous process, it has been shown that the progression is not constant. Gastric carcinomas often remain in the early stage for a long time, in contrast to advanced stages, which often progress rapidly. A retrospective radiologic follow-up study estimated that the doubling time of early gastric carcinomas is several

years, but less than a year for advanced ones.8 Another long-term prospective follow-up study of early gastric carcinomas similarly revealed that many cases remained stable for a median duration of 3.7 years.9 A second, important distinction between the stages of gastric cancer is in macroscopic appearance. This was illustrated in a retrospective study by Nishizawa et al.10 who suggested that the radiological changes noted in gastric carcinomas reflected deep submucosal invasion.

years, but less than a year for advanced ones.8 Another long-term prospective follow-up study of early gastric carcinomas similarly revealed that many cases remained stable for a median duration of 3.7 years.9 A second, important distinction between the stages of gastric cancer is in macroscopic appearance. This was illustrated in a retrospective study by Nishizawa et al.10 who suggested that the radiological changes noted in gastric carcinomas reflected deep submucosal invasion.

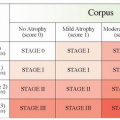

Although the detection of early gastric carcinomas has become increasingly common, the ratio of early to advanced tumors still differs significantly between Japan and the West. In some Japanese institutions, early gastric carcinomas account for approximately half or more of all treated cases, whereas in the West, the incidence is only up to 25%.2,5,11,12 The difference can be attributed to the availability of endoscopic surveillance in Japan combined with mass screening of asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, the differences between Japanese and Western diagnostic criteria for gastric intramucosal neoplasms also are likely to influence the incidence rate of early gastric carcinomas. Classically, Japanese pathologists render a diagnosis of intramucosal carcinoma based solely on the cytologic atypia of neoplastic cells with various degrees of architectural atypia, whereas Western pathologists make a point of identifying a breach of basement membrane and stromal invasion.13 This difference commonly results in a diagnosis of carcinoma by Japanese pathologists for lesions that Western pathologists frequently would classify as high-grade dysplasia (high-grade intraepithelial neoplasm).14 Consequently, there have been several international efforts aimed at resolving the differences, such as the Vienna and Padova classifications.15, 16 and 17

MACROSCOPIC CLASSIFICATION OF GASTRIC CARCINOMA

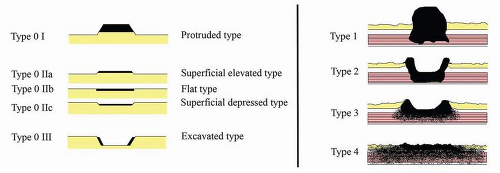

In an effort to provide some consistency in the description of gastric cancers, the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association has established a macroscopic scheme.18 This system derives from two sources: one is the Borrmann classification, well known for advanced gastric carcinomas,19 and the other is a classification for early gastric carcinomas, originally proposed by the Japanese Endoscopic Society.4 The latter was proposed because the Borrmann classification is based mainly on the invasive patterns of carcinomas beyond the mucosal layer, and is not applicable to superficial lesions, whose macroscopic appearance usually changes markedly during progression. Combining these two classifications, gastric carcinomas are macroscopically classified following the scheme shown in Figure 6-1,18 and a reported percentage of each macroscopic type is shown in Table 6-1.20

In this system, in addition to the four types of the Borrmann classification, Type 5 has been added to describe tumors whose appearance cannot be properly classified using Types 1 to 4.

FIGURE 6-1 Macroscopic types of gastric carcinoma according to the rule of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association.18 The classification of early gastric cancer (left) is a 5-tier system with Type 0 corresponding to superficial, flat tumors with or without minimal elevation or depression. For advanced neoplasms (right) the Borrmann classification is followed. The subtypes are defined as follows: Type 1: Polypoid tumors, sharply demarcated from the surrounding mucosa, usually with a broad base; Type 2: Ulcerated carcinomas with sharply demarcated and raised margins; Type 3: Ulcerated carcinomas without well-defined borders, infiltrating into the surrounding wall; Type 4: Diffusely infiltrating carcinomas in which ulceration is usually not a marked feature; Type 5: Nonclassifiable carcinomas that cannot be classified into any of the other types. |

Table 6-1 Percentages of gastric carcinomas by macroscopic type | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Furthermore, Type 0 primarily describes the appearance of early gastric carcinomas, although it also can include advanced carcinomas macroscopically simulating early lesions.18 Type 0 is divided into five subtypes (I, IIa, IIb, IIc, and III) (Fig. 6-1). In addition, tumors with a combined macroscopic appearance are recognized, and terms such as IIa + IIc, or IIc + III are used. The subtypes of Type 0 are based on elevation, evenness, or depression of tumors in relation to the surrounding mucosa (Fig. 6-1). The classification is applicable to radiological and endoscopic images, as well as the macroscopic appearance of resected specimens.4 Adoption of this scheme, especially the delineation of Type 0, has greatly improved communication among surgeons, endoscopists, radiologists, and pathologists in Japan. Recently, the usefulness of the subclassification, especially for endoscopic diagnosis and treatment, has been reconfirmed at the Paris Workshop.21

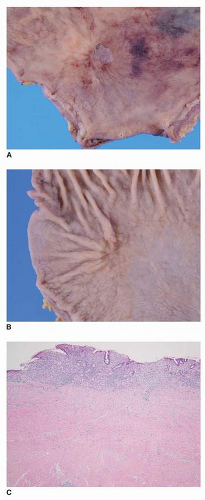

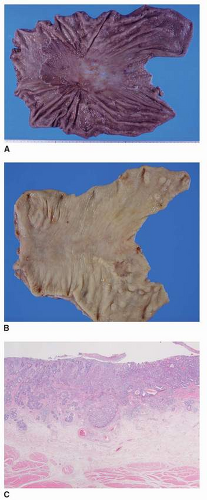

One important change that modifies the macroscopic appearance of early gastric carcinomas is secondary ulceration, which leads to scarring (submucosal fibrosis) when it heals (Fig. 6-2). Hirota et al.6 reported the frequency of secondary ulcer as 64.5% of all early gastric carcinomas, whereas Takizawa et al.20 observed this process less frequently (15.8%). It should be emphasized that Type 0 III originally meant an ulcer lesion with carcinoma just on its edge, previously referred to as an “ulcer cancer.”4,6

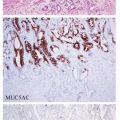

The histologic types of gastric carcinoma influence the macroscopic appearance. For more than half a century, except for rare variants, ordinary gastric adenocarcinomas have been divided into intestinal and diffuse types by the Laurén classification.22 Independently, Nakamura proposed classifying gastric carcinomas into differentiated and undifferentiated types, the former being gland-forming carcinomas (e.g., papillary and tubular adenocarcinomas), and the latter being adenocarcinomas with no or little glandular formation (i.e., signet ring cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma).23,24 However, although Laurén and Nakamura classifications were established based on the respective analysis of advanced carcinomas and minute carcinomas, differentiated lesions mostly correspond to intestinal type and undifferentiated lesions to diffuse type.

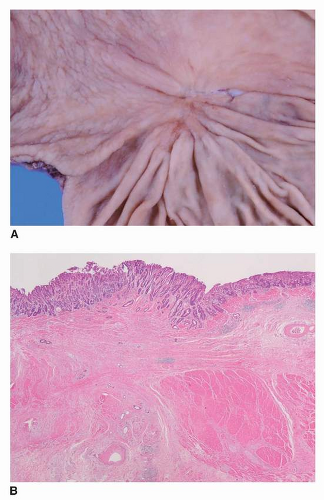

Although the most common macroscopic pattern of early gastric carcinoma is Type 0 IIc, there are some differences between differentiated and undifferentiated tumors, especially when intramucosal.25 Differentiated Type 0 IIc tumors tend to be reddish lesions with ill defined margins or mild elevation at the edge corresponding to the replacement of nonneoplastic glands by neoplastic epithelium. In contrast, undifferentiated Type 0 IIc lesions are characterized by an abruptly depressed margin due to atrophy and/or erosions of the neoplastic mucosa, often with residual islands of nonneoplastic regenerative crypts (Fig. 6-3). Undifferentiated Type 0 IIc lesions also are associated with secondary ulcers more often than are differentiated tumors, which tend to form elevated lesions (Type 0 I, Type 0 IIa).20 Of note, differences are also seen at the stage of advanced gastric carcinoma, with Type 4 tumors predominantly composed of undifferentiated carcinoma.20

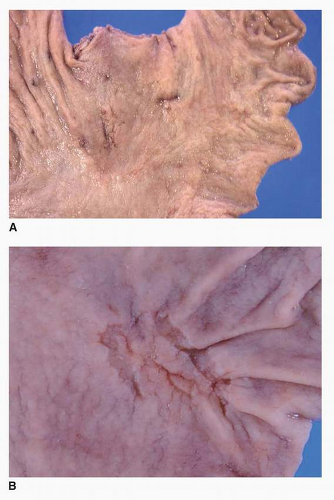

The depth of invasion is another factor influencing the macroscopic appearance of early gastric carcinomas. Most Type 0 IIb carcinomas are intramucosal, although a few cases show submucosal invasion (Fig. 6-4). Mixed patterns, that is, IIa + IIb or IIc + IIb, also can be seen. In that group are signet ring cell carcinomas spreading in atrophic mucosa. However, once the tumor extends into the submucosa, the frequency of combined macroscopic types increases, and even simple Type 0 IIc lesions tend to show an uneven dull depressed surface20 (Table 6-1).

PROGRESSION FROM EARLY TO ADVANCED GASTRIC CARCINOMA

Incipient Phase Gastric Adenocarcinomas

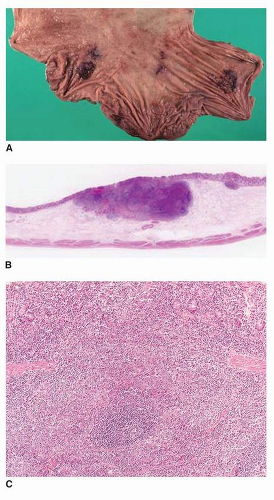

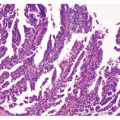

As previously mentioned, the concept of “early” gastric carcinoma does not refer to a chronologically incipient phase. Cases that are small enough in size to be regarded as incipient (<5 mm in diameter) have been termed minute gastric carcinomas (Fig. 6-5). A large series of minute carcinomas (n = 145) was first examined by Nakamura et al.,23,24 and has been collectively examined by several authors.26, 27, 28, 29 and 30 The topographic distribution of these cases was similar to that of larger early gastric carcinomas and advanced tumors, and they often display Type 0 IIb pattern, which can barely be recognized macroscopically, and consequently are usually found during the examination

of a gastrectomy performed for other lesions.24 Minute carcinomas can be either differentiated or undifferentiated, but the former are six times more common.24,27 As small as these neoplasms are, infiltration into the submucosa occurs in 3.3%23,30 to 9%27 of cases. Several routes of invasion can be observed: (a) invasion of the stroma around the vessels that penetrate the muscularis mucosa, (b) infiltration of the vasculature that penetrates the muscularis mucosa, (c) direct invasion and destruction of the muscularis mucosa, and (d) infiltration developing from rare cases of submucosal heterotopic mucosa.31

of a gastrectomy performed for other lesions.24 Minute carcinomas can be either differentiated or undifferentiated, but the former are six times more common.24,27 As small as these neoplasms are, infiltration into the submucosa occurs in 3.3%23,30 to 9%27 of cases. Several routes of invasion can be observed: (a) invasion of the stroma around the vessels that penetrate the muscularis mucosa, (b) infiltration of the vasculature that penetrates the muscularis mucosa, (c) direct invasion and destruction of the muscularis mucosa, and (d) infiltration developing from rare cases of submucosal heterotopic mucosa.31

The Natural Course of Gastric Carcinomas

Few retrospective and prospective follow-up studies have evaluated the course of untreated gastric carcinomas. In a prospective follow-up study of 56 cases, the cumulative 5-year risk for progression to advanced stage was 63.0%.9 This suggests that most untreated early gastric carcinomas, if not all, progress, although they remain at an early stage for several years (median 3.7 years).9 Yet the growth rate can vary considerably. An endoscopic retrospective follow-up study of 72 cases

suggested that the growth of Type 0 IIc early gastric carcinoma was often gradual for 2 to 6 years, whereas some Type 0 IIa + IIc early gastric carcinomas (as well as Borrmann Type 2 or 3 advanced carcinomas) seemed to develop within a few years from nonulcerative, subtle erythematous discoloration, or slightly elevated granular mucosa, or a shallow depression.32 Relatively rapid progression (within 2 years) from endoscopically subtle lesions to Type 4 carcinomas also has been seen.8,32 However, another study reported a longer course (of several years) before Type 4 is seen.33 Rapid growth (within 2 years) of some elevated type carcinomas without obvious, radiologically demonstrated preceding lesions also has been reported.34

suggested that the growth of Type 0 IIc early gastric carcinoma was often gradual for 2 to 6 years, whereas some Type 0 IIa + IIc early gastric carcinomas (as well as Borrmann Type 2 or 3 advanced carcinomas) seemed to develop within a few years from nonulcerative, subtle erythematous discoloration, or slightly elevated granular mucosa, or a shallow depression.32 Relatively rapid progression (within 2 years) from endoscopically subtle lesions to Type 4 carcinomas also has been seen.8,32 However, another study reported a longer course (of several years) before Type 4 is seen.33 Rapid growth (within 2 years) of some elevated type carcinomas without obvious, radiologically demonstrated preceding lesions also has been reported.34

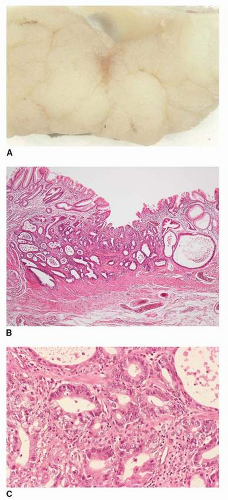

Variable rate of progression from early to advanced carcinoma also is implied by the analysis of resection specimens. Kodama et al. classified the growth patterns of early gastric carcinomas into two types: The superficially spreading type, which is over 4 cm in diameter and confined to the mucosa or with very limited invasion to the submucosa. The second type, on the other hand, the penetrating growth type is <4 cm in diameter with wide submucosal invasion (Fig. 6-6).35

The clonal origin of superficial widely spreading depressed-type gastric carcinomas was demonstrated with the HUMARA assay, implying that the lesions remained in the mucosa for a long time and do not represent the coalescence of several lesions.36

As previously noted, secondary peptic ulceration commonly occurs in depressed type early gastric carcinomas, and a recurrent cycle of ulceration, healing, and reulceration can be observed. Such carcinomas tend to remain at an early stage for an extended period, which is partly explained by tumor cell loss and the deterrent effect of fibrous scarring against invasion.3,8 Of note, although ulceration is more frequent in undifferentiated neoplasms, differentiated type neoplasms are more likely to show submucosal invasion.20

As they progress to advanced stages, some early gastric carcinomas, especially those of depressed type, retain the same endoscopic appearance and do not acquire a macroscopic appearance that could be classified by using the Borrmann classification.8,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree