Ear

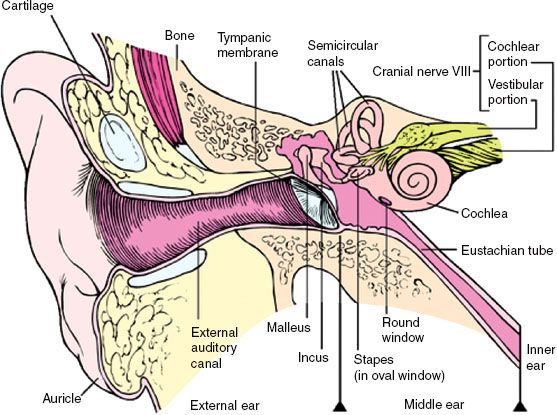

FIGURE 39.1. Ear anatomy.

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

The external, middle, and inner components of the ear develop from the three embryonic layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.

The external ear consists of the auricle or pinna, the external auditory meatus (canal), and the tympanic membrane (Fig. 39.1). The auricle is composed of elastic cartilage covered with skin. The external auditory meatus connects the tympanic membrane to the exterior and is approximately 2.4 cm long. The outer third is cartilaginous, and the inner two-thirds is bony and slightly narrower. The external auditory canal is anterior to the mastoid process and posterior to the parotid gland at the temporomandibular joint. The inferior border of the canal lies near the jugular bulb and the facial nerve as it descends through the stylomastoid foramen. The skin lining the auditory canal is continuous with that of the auricle, and in the outer one-third of the canal, it contains hair follicles and sebaceous and ceruminous glands. The tympanic membrane, which is made of multiple layers of squamous epithelium, separates the auditory canal from the middle ear.

The middle ear houses the auditory ossicles, the tympanic cavity, and opens into the eustachian tube to communicate with the pharynx. The middle ear cavity is lined with a mucoperiosteal membrane, and the eustachian tube is lined with stratified columnar epithelium and has numerous mucous glands in the two-thirds of the tube closer to the pharynx. The overall length of the eustachian tube is 3.5 cm.1

The inner or internal ear lies in the petrous portion of the temporal bone and consists of the bony labyrinth and the membranous labyrinth. The membranous labyrinth, which holds the organ of hearing, is housed within the bony labyrinth. The cochlea, which is responsible for hearing, and the vestibule, which is responsible for balance, are part of the inner ear.

Blood supply to the auricle and the external auditory canal come from branches of the posterior auricular artery and the superficial temporal artery, which arise from the external carotid artery. Blood is supplied to the middle ear region from branches of ascending pharyngeal and middle meningeal arteries and from the artery of the pterygoid canal. The inner ear is supplied by the internal auditory artery, which is a branch of the basilar artery, and from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery.

The nerves innervating the ear include cranial nerves V, VIII, IX, and X. The eighth cranial nerve or vestibulocochlear nerve is responsible for auditory and vestibular function. It exits from the brainstem between the pons and the medulla and follows the internal acoustic meatus.

For the external ear, lymphatic vessels of the tragus and anterior external portion of the auricle drain into the superficial parotid lymph nodes. The posterior and superior aspects of the auricle drain into the retroauricular lymph nodes, and the lobule drains into the superficial cervical group of lymph nodes. Lymphatics from the middle ear and the mastoid antrum pass into the parotid nodes and into the upper deep cervical lymph nodes. The lymphatics in the middle ear and eustachian tube are rather sparse, and the inner ear has no lymphatics.

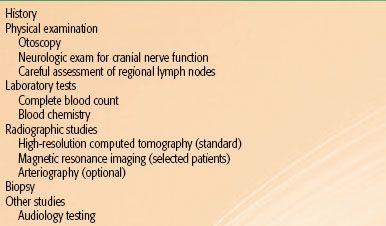

TABLE 39.1 DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION FOR CARCINOMA OF THE EAR

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Malignant disease of the auricle is common, but cancers of the middle ear and external auditory canal are rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 per million people.2,3 Tumors of the external ear are most often cutaneous malignancies and may be related to sun exposure.4,5 Other predisposing factors described, although their significance is in question, are otorrhea, chronic eczema, chronic dermatologic conditions, and chronic ulcerations from trauma.6

Tumors of the external ear most commonly occur in patients 60 to 70 years of age; tumors of the middle ear and the mastoid are more common in patients 40 to 60 years of age.7,8 More women than men have middle ear tumors, but more men have tumors of the external ear.9,10

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

External Ear

Basal cell carcinomas are more common than squamous cell carcinomas in the external ear, with a ratio of 1.3 to 1.7 They present as small ulcerations, mostly on the helix.11,12 For squamous cell carcinomas, lymph node metastases occur in approximately 10% to 15%.13 The common sites of lymph node metastases in order of frequency are the parotid gland, the upper deep cervical chain, and the postauricular nodes.8,13 The rate of regional metastasis is higher in advanced disease and may involve the level 5 cervical lymph node group.14

External Auditory Canal

Most patients present with symptomatic lesions of the external auditory canal. Pruritus and pain are common. Swelling behind the ear, decreased hearing, and facial paralysis are seen in advanced cases. Spread of the tumor into the lymphatic areas is more common than to other areas of the ear. Tumors arising in the cartilaginous portion of the canal invade the cartilaginous walls and spread into the bony canal areas. However, those arising in the bony canal have a more effective barrier (preventing spread), and therefore progress predominantly along the main axis of the canal, eventually invading the middle ear or the cartilaginous part of the canal. Distant metastases are rare.

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

Table 39.1 summarizes workup and diagnostic procedures. A history and physical including otoscopy and careful lymph node exam should be performed. Neurologic exam finding of cranial nerve deficits may be an indication of advanced disease. A baseline audiology testing should be performed prior to any treatment.

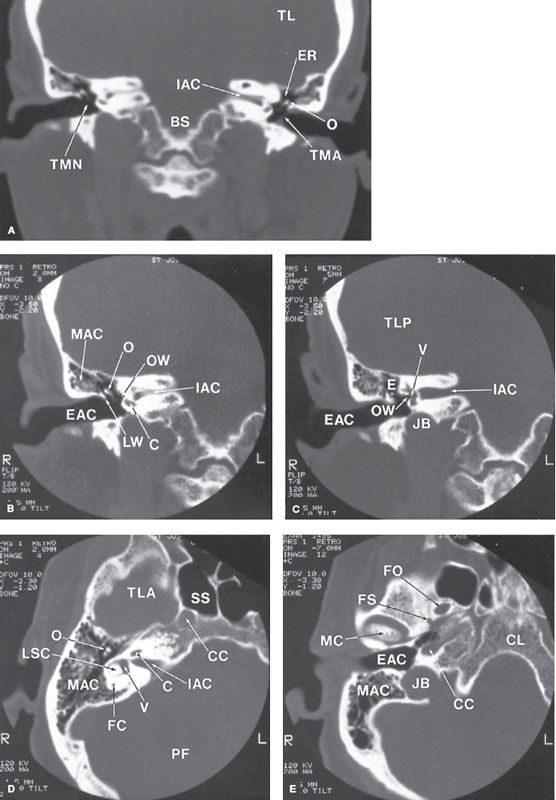

Both multidetector computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) play an important role in visualizing tumors of the ear.15 CT can show abnormal soft tissue, soft tissue enhancement, distortion of the normal tissue planes, and bone destruction (Fig. 39.2). Recent advances in CT allows evaluation not only of temporal bone, infratemporal fossa, and base of skull, but also of the anatomic structures of the middle and inner ear in greater detail.16 CT scans can help to determine the extension and the operability of tumors.17,18 Sometimes magnetic resonance imaging can provide excellent delineation of soft tissue tumor margins, muscle infiltration, intracranial extension, and vessel encasement.19,20 Except in selected cases, angiography and jugular venography have also been abandoned in favor of CT.

Diagnosis is always established by biopsy and occasionally by aspiration of the exudative material or by surgical exploration. A bone scan may be done to determine the changes in the temporal bone around the tumor, but it provides very nonspecific information and is not a recommended method of evaluation.

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

Approximately 85% of the tumors involving the auditory canal, middle ear, and mastoid area are squamous cell carcinomas. Infrequently, basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas, and melanomas are seen.21 Even rarer are sarcomas, specifically embryonic rhabdomyosarcomas. Ceruminous gland tumors and papillomas rarely arise in the auditory canal.6,21,22 Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear is rare, and only 50 cases have been reported in the literature.23,24 Endolymphatic sac tumor, or aggressive papillary middle ear tumors, are distinct from middle ear adenomas and act aggressively. They are characterized by slow growth but extensive local invasion and bone destruction.25,26

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Lesions of the external ear are usually more easily controlled than are lesions of the middle ear or mastoid. External ear lesions are usually diagnosed earlier; they are mostly cutaneous, and adequate surgery or radiation therapy is usually effective.8,27,28 Presence of large lesions involving the middle ear and those with extension into the temporal bone is a poor prognostic sign and more difficult to treat.2,29,30 There does not appear to be a correlation between tumor differentiation, positive margins, or perineural disease and survival, although they may serve as a predictor for local control in tumors involving the temporal bone.29,31,32 Seventh nerve palsy associated with middle ear tumors indicates poor local control.32,33 Spread of tumors to the lymph nodes usually indicates a poor prognosis because this is often a late event in the natural history of the disease.34

FIGURE 39.2. Normal anatomy of the ear. A–C: Coronal sections. D, E: Transverse sections. BS, brainstem; C, cochlea; CC, carotid canal; CL, clivus; E, epitympanum; EAC, external auditory canal; ER, epitympanic recess; FC, facial canal; FO, foramen ovale; FS, foramen spinosum; IAC, internal auditory canal; JB, jugular bulb; LSC, lateral semicircular canal; LW, lateral wall, epitympanic recess (scutum); MAC, mastoid air cells; MC, mandibular condyle; OS, ossicles; OW, oval window; PF, posterior fossa; TLA, temporal lobe, anterior portion; TLP, temporal lobe, posterior portion; TMN, tympanic membrane, normal appearance; TMA, tympanic membrane, abnormally thickened; SS, sphenoid sinus; V, vestibule. (Courtesy of Robert Gresick, MD, DePaul Health Center, St. Louis, MO.)

STAGING

STAGING

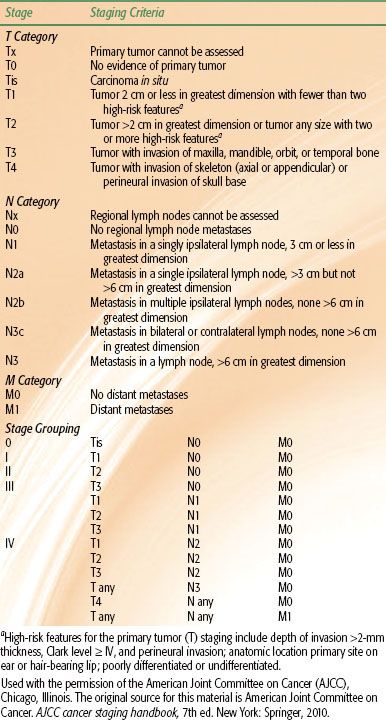

The seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual35 includes the external ear in its staging system under Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Other Cutaneous Carcinomas (Table 39.2). A group from the University of Pittsburgh proposed a staging system for squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal and temporal bone, which was updated in 2002.36–38 The primary tumor stage is determined by the level of bony erosion, size, and involvement of the middle ear. Lymph node disease is considered advanced stage with poor prognosis. This staging system has often been cited in the literature.2,39–48

TABLE 39.2 THE AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE ON CANCER AND INTERNATIONAL UNION AGAINST CANCER STAGING SYSTEM FOR EAR CANCER

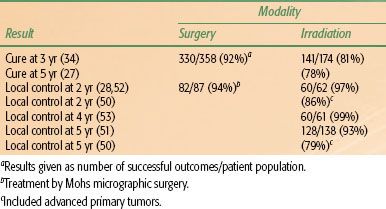

TABLE 39.3 TREATMENT OF CARCINOMA OF THE EXTERNAL EAR

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

External Ear

Tumors of the external ear are most often treated with limited surgery or external radiation therapy. Treatment in early stages with irradiation is usually in the form of megavoltage electron beam therapy or orthovoltage.49,50 Most radiation techniques have been fairly successful in the treatment of lesions in this area, with local control rates of 80% to 97%.27,51–53 Caccialanza et al.27 reported a 5-year cure rate of 78% with a mean follow-up of 2.4 years for 115 carcinomas of the pinna treated with definitive kilovoltage radiation to a total dose of 45 to 70 Gy in 2.5- to 5-Gy fractions given two to three times per week. Surgery is beneficial if the lesion has invaded the cartilage of the ear or extends medially into the auditory canal. If squamous cell carcinoma of the external ear is treated with surgery alone, there is a recurrence rate of 14% to 19%.8,54 Mohs surgery is another option, with reported local recurrence rates of 5% to 7%.28,55 Advanced lesions involving a significant portion of the ear canal are managed with a combination of irradiation and surgery. Palmer and Snell56 describe the use of radical soft tissue and subtotal temporal bone excision with deltopectoral flap coverage for extensive tumors of the auricular area.

Treatment of draining lymphatics is normally not required for early stages of external ear tumors.12 Afzelius et al.11 indicate that lesions >4 cm and those with cartilage invasion have an increased risk of nodal spread; they recommend prophylactic neck dissection.57 Most investigators do not agree with this approach because the overall chance of lymph node involvement in tumors of the external ear is only 16%. Osborne et al.58 reported that parotidectomy may be unnecessary in management of advanced auricular carcinoma without clinically positive parotid disease.

Interstitial irradiation using afterloading 192Ir, particularly for tumors smaller than 4 cm, is also an effective method of treatment, affording excellent local control with good cosmesis31,53 (Table 39.3).

Radical surgery followed by postoperative radiation therapy is an acceptable method of treatment for more advanced lesions of the external auditory canal and lesions in the middle ear and mastoid.30,46,59 Pfreundner et al.30 recommended a postoperative radiotherapy dose of 54 to 60 Gy for patients with negative margins. Positive margins warrant higher doses of 66 Gy because of higher recurrence rates. Except in tumors that are detected early, neither modality alone is considered optimal, and a combination of the two produces the best results.

Lesions of the outer part of the auditory canal require local excision with at least a 1-cm margin between the lesion and the tympanic membrane if there is no radiographic evidence of invasion of the mastoid. Surgery for tumors of the auditory canal is performed through a U-shaped incision with elevation of the flap from below. A split-thickness skin graft is usually required to cover the deficit along the auditory canal.

When the tumor involves the bony auditory canal and impinges on the tympanic membrane but does not involve the middle ear or the mastoid, a partial temporal bone resection may be necessary; in this procedure, the auditory canal, tympanic membrane, malleus, and incus are removed along with the temporomandibular joint, and the defect is grafted with a split-thickness skin graft. Postoperative radiation may be indicated, depending on margin status.

Middle Ear and Temporal Bone

In management of temporal bone tumors originating from the middle ear and mastoid area, surgical options include subtotal temporal bone resection, total temporal resection, lateral temporal resection, or mastoidectomy. Complete resection with clear margins may be difficult to achieve, given that important structures reside around the temporal bone.40,57,60–63 Postoperative radiation therapy is recommended and increases local tumor control.30,40,64,65 In studies that suggest limited benefit of postoperative irradiation, the results may be related to the extent of the tumor.66 Given that total and subtotal temporal bone resection can result in significant morbidity, some investigators favor limited surgery with postoperative or perioperative radiation.67,68 Chemotherapy has not been beneficial in tumors of the ear. A study on preoperative chemoradiotherapy suggested improvement in estimated survival of advanced disease, but additional trials are necessary to determine efficacy.69

FIGURE 39.3. Example of treatment portal for tumor of the middle ear involving the petrous bone. The mastoid is included in irradiated volume.