(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The operations discussed in this chapter have been described individually and in detail elsewhere. This chapter focuses on a common feature of these procedures, the technique of dissection within the mesentery (or mesocolon) and exposure of the mesenteric (or mesocolic) branches, and emphasizes its surgical importance as a unifying feature of various procedures.

The need to resect a segment of small bowel for various benign conditions is quite common in general surgery. In order to free the segment of bowel to be resected from the adjacent proximal and distal loops of bowel, it is necessary, of course, to remove a segment of the adjacent mesentery. For benign conditions, a small portion of the adjacent mesentery needs to be removed. Usually, the small bowel mesentery or the large bowel mesocolon adjacent to the segment to be removed is divided between clamps, which are then ligated serially. This technique works well in most cases, and it is simple and expeditious.

The mesentery of the bowel consists of peritoneal leaves; between them are adipose tissue, lymphatic tissue, and the arterial and venous vascular supply of the corresponding bowel segment. Often there is enough adipose tissue in the mesentery to preclude clear visualization of the arterial and venous branches on simple inspection. When pairs of hemostats are applied sequentially in the mesentery and the tissue between them is divided, bleeding often occurs because the jaws of the clamps do not cross the entire width of a vascular leash, which obscures as the latter is often from the surrounding adipose tissue, necessitating the hurried application of additional clamps. The ligation of the vessels under the clamps in these circumstances is also less secure. The division of the mesentery between clamps, “blindly” applied, may include branches of the mesentery of the adjacent segment of bowel, whose sacrifice may compromise the blood supply to the bowel at the point where it is to be divided. The result would be ischemia of the edge of one of the ends of the bowel segments that are to be anastomosed. If this ischemia is not recognized intraoperatively, the result may be a postoperative anastomotic leak. In contrast, when the peritoneal leaf is incised on one side and the adipose tissue is gently incised with half-opened Metzenbaum scissors, the vessels in the mesentery are exposed and those pertinent to the bowel segment to be removed are surrounded sequentially by ligatures, which are tied proximally and distally with the vessel(s) divided in between. This method of dissecting the vascular branches within the mesentery provides more precise and secure ligation and lessens the risk of venous bleeding that is likely to occur with the use of clamps, which are often heavy and are likely to disrupt a venous tributary as the ligature is applied around the clamp. Dissection in the mesentery of the bowel is a refinement in surgical technique that we recommend even for ordinary bowel resections, particularly in the presence of a thickened mesentery. It becomes a necessity in the procedures described below.

Malignant Tumor Involving the Bowel

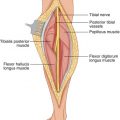

In the case of an adenocarcinoma or other malignant tumor involving the bowel, it is often necessary to remove a segment of the mesentery corresponding to the bowel to be resected so as to procure a wide margin around the tumor and remove any lymphatic spread within the mesentery. The segment of small bowel mesentery to be removed is roughly triangular, with the apex of the triangle being at the base of the mesentery. To obtain wide resection of the mesentery corresponding to the bowel to be removed, it thus becomes necessary to dissect within the mesentery by incising the peritoneal leaf proximal and distal to the purported division of the mesentery, starting from the proximal and distal points where the bowel is to be divided. The peritoneal leaf is incised on at least one side proximal and distal to the area to be removed (preferably both peritoneal leafs are incised), and the vessels within the mesentery are outlined and divided in such a way as to accomplish the desired goal of removing the appropriate portion of the mesentery while preserving the vessels supplying loops adjacent to the bowel segment to be resected. The difference between compromising and preserving the branches supplying the edge of the bowel to remain behind is often a matter of millimeters. Both the proximal and distal incisions adjacent to the tumor of the involved mesentery are exposed, and the dissection within the mesentery is carried out so that the branches clearly coursing in the direction of the bowel segment to be removed are ligated and divided, whereas those coursing in a direction indicating their commitment to supplying the areas of the bowel to stay behind are preserved. To clearly expose the mesenteric vessels after the peritoneal leaf on at least one side is incised proximally and distally, the adipose tissue is incised with half-opened Metzenbaum scissors, using a slight amount of force while vascular branches are being exposed and dealt with appropriately according to their size and location within the mesentery. Attention must be paid particularly at the base of the mesentery, where one may encounter the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and, to its left and at a slightly deeper plane, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). These are more likely to be encountered in resections of proximal segments of the small bowel with a deep dissection within the mesentery for the removal of the corresponding portion. In the distal segments of the bowel, such as the ileum, the SMA and SMV have already been exhausted and terminal branches (e.g., the ileocolic branch) are found instead. In this case, it is not so critical to dissect on the surface of the superior mesenteric vessels, as they are no longer present, having given off branches to the proximal portions of the bowel. The jejunal and proximal ileal branches come off the left side of the SMA and the venae comitantes reach the left side of the SMV. The last branch of SMA is the ileocolic artery, which communicates through an arcade to the left with the termination of SMA and an arcade to the right with the marginal artery of the distal ileum. The right colic artery and vein are connected to the right side of the distal portion of the superior mesenteric vessels and supply the right side of the colon. The middle colic artery and vein are connected to the superior mesenteric vessels just below the inferior border of the pancreas and issue forward from their surface within the transverse mesocolon and toward the mid-transverse colon. The middle colic artery divides into right and left branches, which continue along the mesenteric border of the colon to meet the communication on the right side with the right colic artery and on the left side with the left colic artery arising from the inferior mesenteric artery. The sigmoidal branches arise from the distal part of the inferior mesenteric artery, which terminates in the superior rectal artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree