Diagnostic Modalities for Endometrial Carcinoma

Reagan Street MD

Tri A. Dinh MD

Endometrial cancer is more commonly diagnosed than ovarian, cervical, vulvar, and vaginal cancer combined. Management of endometrial cancer, whether conservative or radical, must take into consideration not only the postmenopausal patient, but also the young patient who has not completed her family. Nulligravidity contributes to endometrial cancer risk, so women younger than 40 are often desirous of fertility-sparing treatment.1 Research into techniques to accurately diagnose and preoperatively evaluate endometrial cancer reflects these concerns. Precise assessment of the extent of disease is augmented by multiple diagnostic modalities.

GENERAL MEDICAL EVALUATION

Endometrial cancer patients are typically obese and postmenopausal and are at high risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Prior to surgical treatment, it is imperative to do a basic preoperative evaluation including electrocardiogram, chest x-ray, and basic laboratory evaluation to assess electrolytes, hemoglobin, and renal function.2 A chest x-ray can detect cardiopulmonary problems, pleural effusions, and pulmonary metastasis.2 Along with these essential tests, various imaging modalities may be used to evaluate for myometrial invasion, cervical extension, and lymph node or widespread metastasis (Fig. 5-1).

In cases where early-stage, grade 1 disease is presumed, imaging modalities may not be necessary.2 Patients with high-risk clear cell or papillary serous histology are more likely to present with extrauterine disease, and preoperative imaging is helpful in presurgical planning.2 Finally, preoperative imaging is helpful to triage patients who may benefit from consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or extended surgical staging if this is not a procedure that was originally planned.

PRETREATMENT EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

When a patient presents with symptoms consistent with the possibility of endometrial cancer, it is vital for the physician to perform a complete history and physical examination. Family history may elicit conditions such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or mutations in the MLH1 and MSH2 mismatch repair genes.1 These hereditary conditions

increase the incidence of early-onset development of endometrial cancer from 0.2% in the general population to 25% in a woman less than 50 years old with these mutations.1

increase the incidence of early-onset development of endometrial cancer from 0.2% in the general population to 25% in a woman less than 50 years old with these mutations.1

FIGURE 5-1: Pulmonary nodules in a late-stage endometrial cancer on chest x-ray, lateral and anterior-posterior views, respectively. |

A full physical examination will include lymph node survey of the neck, axilla, and groin, as well as complete pelvic and rectal examination to evaluate for pelvic spread of disease.1 Often, patients are older and have multiple coexisting medical morbidities. These conditions may render a patient a poor surgical candidate and alert the physician to certain findings that may contraindicate a primary surgical treatment.1 Diabetes and hypertension are common comorbidities, and it is important to have blood glucose levels and blood pressure under control prior to surgery. Anesthetic and surgical risks increase in women who are obese and women with cardiopulmonary disease.1

Papanicolaou Smear

The importance of the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear in screening for cervical cancer is well established. Unfortunately, its usefulness in endometrial cancer screening is limited.3 Several studies have been performed to evaluate the use of Pap smears for endometrial cancer screening, but the average sensitivity is only about 43%.4 Several small studies report that abnormal Pap smears are found in 100% of papillary serous or clear cell endometrial cancer and in greater than 60% of endometrioid-type cancer.4 Another study showed a sensitivity of only 26% in detecting endometrial cancer overall; however, the authors note that the Pap smear may have improved sensitivity with higher grade disease.5 The huge variations in these findings make the clinical utility of the Pap smear in detection of endometrial cancer quite low.

Occasionally, cervical cytology samples show benign endometrial cells. Beal et al.6 showed that this occurred in approximately 0.9% of women 40 years of age or older; the majority of these women are completely asymptomatic.6 If benign endometrial cells are an

incidental finding in an otherwise asymptomatic premenopausal woman, it is exceedingly rare to find endometrial pathology.7 No further evaluation is indicated. However, if a woman is symptomatic with irregular or heavy vaginal bleeding, the finding of endometrial cells on Pap smear indicates the need for further investigation.7 In postmenopausal women, the finding of endometrial cells on Pap smear almost always necessitates endometrial sampling.8

incidental finding in an otherwise asymptomatic premenopausal woman, it is exceedingly rare to find endometrial pathology.7 No further evaluation is indicated. However, if a woman is symptomatic with irregular or heavy vaginal bleeding, the finding of endometrial cells on Pap smear indicates the need for further investigation.7 In postmenopausal women, the finding of endometrial cells on Pap smear almost always necessitates endometrial sampling.8

The current American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology recommendations for atypical endometrial cells or abnormal glandular cells provide for further evaluation with colposcopy in conjunction with endocervical curettage, endometrial biopsy, and human papillomavirus testing. More often than not, cervical epithelial neoplasia is found in cases where atypical glandular cells are found on cervical cytology, but the endometrial cavity still warrants evaluation.8 Endometrial biopsy is indicated if a patient is less than 35 years of age and presents with vaginal bleeding that cannot be explained or has symptoms of chronic anovulation. If the patient is greater than 35 years of age, endometrial biopsy is almost always indicated with the finding of abnormal glandular cells but especially if atypical endometrial cells are noted on cytology. Less than 2% of women younger than 40 years of age have endometrial cells found on Pap smear requiring evaluation. Younger women rarely have pathology associated with the finding of endometrial cells on Pap smear; however, in menopausal women, it is critical to search for a pathologic cause.8

Sometimes, women who have had a hysterectomy for benign reasons have Pap smears of the vaginal cuff performed. If this occurs and benign glandular cells are found, no further investigation is needed.8 However, if a woman has a hysterectomy for cervical or endometrial cancer, Pap smear surveillance of the vaginal cuff is critical to evaluate for evidence of recurrence. Implications of Pap smear in evaluation of recurrent disease will be discussed later.

At time of initial presentation, a positive Pap smear is predictive of poor prognosis and future endometrial cancer recurrence. Histologic subtypes of papillary serous and clear cell endometrial cancer are more likely to be diagnosed after finding abnormal cells on cervical cytology than endometrioid-type endometrial cancer. The presence of abnormal endometrial cells on cervical sampling is also a predictor of poor prognosis, as indicated by the increased likelihood of severe myometrial invasion and nodal metastases.9 Increased grade of endometrial cancer regardless of histologic subtype is associated with having an abnormal Pap smear.9 Brown et al.9 determined that initial abnormal cytology leads to endometrial cancer recurrence in 12% of patients, as opposed to only 4% of patients with normal initial Pap smear findings. The same study showed that 19% of patients who were diagnosed with papillary serous or clear cell subtypes had abnormal cervical cytology compared with only 7% of endometrioid endometrial cancer patients.9

Endocervical Curettage

Endocervical curettage (ECC) is another method of evaluating women who present with abnormal cervical cytology or vaginal bleeding. ECC can be positive without any evidence of disease on imaging.2 This finding may represent microscopic cervical involvement or possible contamination from the uterus.2 ECC is included in a procedure called a fractional dilation and curettage (D&C), which attempts to isolate endometrial curettage from ECC. Distinguishing cervical involvement from endometrial contamination on fractional D&C is inaccurate. ECC is a poor method for evaluation of cervical extension of endometrial cancer because it has a false-positive rate of up to 50%.2 False-negative results are also possible, so physicians must use other techniques to determine cervical involvement if there is high

suspicion.2 Cervical involvement does not preclude surgical treatment, and often the presence of cervical involvement is only defined at the time of hysterectomy with frozen section pathology.

suspicion.2 Cervical involvement does not preclude surgical treatment, and often the presence of cervical involvement is only defined at the time of hysterectomy with frozen section pathology.

Endometrial Sampling

Endometrial sampling is the key step in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Premenopausal women who are anovulatory are at higher risk for endometrial neoplasia and require endometrial sampling to work-up abnormal uterine bleeding. All postmenopausal women with vaginal bleeding require endometrial sampling. Ten percent of postmenopausal women who present with this classic symptom will have cancer on biopsy.2 Combined risk factors of age greater than 70 years, type 2 diabetes, and nulliparity increase risk of neoplasia in women with symptomatic bleeding.2 Eighty-seven percent of these patients are diagnosed with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer on biopsy.2 Three percent of women with symptomatic bleeding and none of these risk factors are diagnosed with endometrial cancer on endometrial biopsy.2 Accurate history and physical prior to endometrial sampling allows a physician to appropriately counsel patients.

Endometrial biopsy is often performed in an outpatient setting with minimal discomfort to the patient and no need for anesthesia. Adequate sampling is a must, and if not obtained, further investigation with more invasive techniques is warranted. Endometrial biopsy in the United States is most often performed with a disposable plastic endometrial suction curette (e.g., Pipelle; CooperSurgical, Trumbull, CT). The patient is placed in lithotomy position, and after placement of a speculum, a curette is inserted through the cervix into the uterine cavity, and a biopsy specimen is obtained.

Risks of endometrial biopsy include pain and bleeding. Infrequently, uterine perforation may occur, but this is almost always benign and does not require any action other than observation. Rarely, a specimen is unobtainable due to cervical stenosis. Endometrial biopsy in the outpatient office setting is a blind procedure and can produce a false-negative result due to lack of tissue representing the entire endometrium. Positive tests are diagnostic, but negative tests often require further endometrial cavity evaluation.10

Endometrial biopsy collection fails in approximately 8% of cases when a Pipelle device is used, according to a literature review by Clark et al.10 They evaluated 11 studies with more than 1,000 patients and found inadequate samples in up to 13% of specimens collected via the Pipelle and 15% of specimens for all methods.10 Other tools used to collect endometrial samples are the Vabra Aspirator (Berkeley Medevices, Richmond, CA) and the Z sampler device (Zinanti, Chatsworth, CA). The Vabra Aspirator has been found to be less accurate overall in diagnosing hyperplasia and endometrial cancer but is still widely used.3

In postmenopausal women, physicians may be unable to perform office endometrial sampling, and even when a sample is obtained, the specimen may still prove inadequate for analysis.10 Clark et al.10 found an overall failure rate of 12% but a higher inadequate sampling rate of 22% for all methods in postmenopausal women. The authors concluded that outpatient diagnosis via endometrial biopsy is a valid and valuable tool in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially when negative results are further evaluated in cases where clinical suspicion is high.

The strength of Pipelle endometrial sampling is further demonstrated by Fakhar et al.,11 who evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of endometrial biopsies in 100 patients. D&C following the biopsy served as the “gold standard” for comparison.11 If Pipelle sampling indicated endometrial carcinoma,

endometrial hyperplasia, or secretory endometrium, then sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were each 100%.11 For endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, sensitivity and NPV remained 100%, whereas specificity slightly decreased to 98% and PPV decreased to 80%.11 These results further authenticate the use of outpatient endometrial sampling with a Pipelle device as a cost-effective, low-risk option with excellent sensitivity and specificity.

endometrial hyperplasia, or secretory endometrium, then sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were each 100%.11 For endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, sensitivity and NPV remained 100%, whereas specificity slightly decreased to 98% and PPV decreased to 80%.11 These results further authenticate the use of outpatient endometrial sampling with a Pipelle device as a cost-effective, low-risk option with excellent sensitivity and specificity.

Office endometrial biopsy does have limitations in cases where an endometrial polyp is present. Tanriverdi et al.12 suggest that if a polyp is suspected, D&C is necessary. They also confirmed previous findings that endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal women may produce an inadequate sample in up to 22% of cases and again suggest D&C in such cases.12 They did not find the high 100% sensitivity and specificity for endometrial carcinoma found by Clark et al.,10 but they did evaluate the combination of transvaginal ultrasound and Pipelle biopsies, finding close to 100% sensitivity and specificity when these methods are combined.11,12 Tanriverdi et al.12 also proposed that outpatient biopsy be used only in low-risk patients without high suspicion of hyperplasia with atypia or endometrial cancer and that patient with high risk for cancer be more carefully and completely evaluated with formal endometrial curettage. Most physicians prefer an attempt at outpatient sampling in all patients, with appropriate follow-up if suspicion remains elevated despite a negative result.

Routine screening for endometrial cancer does not exist, but certain groups warrant some method of evaluation. Patients with known HNPCC should undergo annual endometrial biopsies starting at age 35 according to the American Cancer Society.2 HNPCC increases the lifetime risk of endometrial cancer from 3% to 20%.2 Some physicians advocate that women on tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer should undergo endometrial sampling for screening, whereas most physicians advise prompt evaluation only in symptomatic women.2 Most oncologists and other authorities do not advocate routine evaluation with ultrasound or endometrial biopsy in women on tamoxifen.2 The American Cancer Society does not recommend endometrial cancer screening for women on tamoxifen.2

Dilation and Curettage

D&C is the gold standard for diagnosis of endometrial cancer.3 A D&C requires general or regional anesthesia in an operating room and is often performed with hysteroscopy to completely evaluate the endometrial cavity. Women with endometrial polyps, cervical stenosis, or insufficient sampling on endometrial biopsy who remain at high suspicion for endometrial cancer require endometrial curettage in the operating room. For patients contemplating medical therapy of endometrial cancer to preserve future fertility, complete evaluation of the endometrium with curettage is crucial.1 Hysteroscopy involves using a camera inserted into the cervix after adequate dilation. The entire endometrial cavity may be visualized, and directed biopsies may be taken.

The accuracy of office endometrial sampling versus endometrial curettage has been compared, and results are mixed. Larson et al.13 showed that D&C correctly identified the tumor grade of 77% of endometrial cancers compared with 58% of office samples taken with the Z sampler, one device for outpatient endometrial sampling. Often, the cancers were undergraded (i.e., given a lower tumor grade than the grade found at hysterectomy).13 Preoperatively, because there is no definitive way to evaluate depth of invasion, tumor grade is of utmost importance to guide the decision of whether or not to perform complete lymphadenectomy for surgical staging.13 For example, patients with grade 3 endometrial carcinoma, regardless of myometrial invasion, would undergo surgical staging with both pelvic and paraaortic

lymphadenectomy due to a higher risk of nodal metastasis. In contrast, a patient with grade 1 endometrioid endometrial cancer may be managed with a more conservative surgical procedure.13

lymphadenectomy due to a higher risk of nodal metastasis. In contrast, a patient with grade 1 endometrioid endometrial cancer may be managed with a more conservative surgical procedure.13

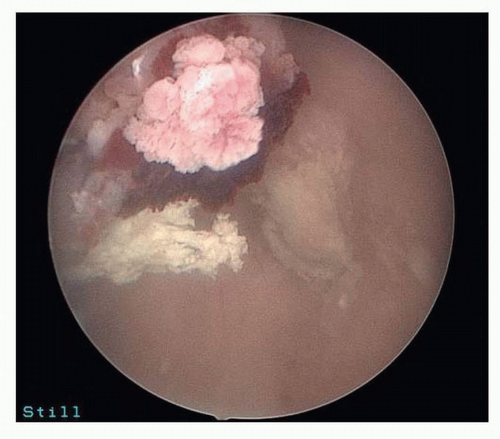

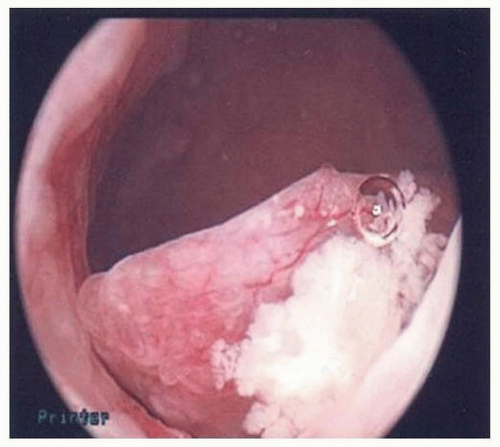

FIGURE 5-2: Hysteroscopy showing polyp suspicious for cancer (later proven serous endometrial cancer by pathology). |

Hysteroscopy is often performed with D&C. Ben-Yehuda et al.14 showed that hysteroscopy does not increase the diagnostic accuracy of the endometrial curettage. They reviewed medical records of 403 patients who underwent both uterine curettage and hysteroscopy and noted that there was only 52% concurrence in the diagnosis of hyperplasia via hysteroscopic impression versus final pathology findings. Only 10 patients in their study had endometrial cancer found on D&C, but hysteroscopic impression of carcinoma was only noted in the operative notes of 2 of these patients. Two patients in their study had endometrial cancer diagnosed within 6 months but were not diagnosed with either modality, refuting the idea that hysteroscopy might catch some cancers that curettage may miss14 (Figs. 5-2,5-3 and 5-4).

In benign gynecologic conditions, when hysteroscopy is used to detect polyps and submucosal leiomyomata, research shows that diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding does improve with hysteroscopy combined with endometrial curettage.14 Uterine curettage was only able to detect 32% of polyps and 6% of leiomyomata in this review, confirming that hysteroscopy aids in diagnosis in some situations.14 The review by Ben-Yehuda et al.14 of 403 patients identified three uterine perforations, none of which necessitated exploratory laparotomy. Occasionally, diagnostic laparoscopy may be necessary after uterine perforation to evaluate the intra-abdominal organs for damage.15 Complications due to general or regional anesthesia can also be encountered during hysteroscopy. In addition, there is the added possibility of complication from the distending media used to visualize the endometrial cavity.14

Distending media can be isotonic or hypotonic fluid or carbon dioxide gas. Most gynecologists prefer to use normal saline to distend the uterine cavity to improve visualization. If uterine perforation is encountered, normal saline will not harm the patient unless a large amount is deposited. Pulmonary or cerebral edema from extensive intravascular absorption is a rare complication of excess fluid balance after hysteroscopy, and the patient should be observed postoperatively if this is encountered. Hypotonic fluids such as glycine and sorbitol can lead to electrolyte abnormalities with a relatively minimal amount of positive fluid balance.15 Accurate assessment of fluid deficits is important in preventing these complications. Carbon dioxide may also be used as a distending media. If the intrauterine pressure is allowed to get too high, venous gas embolism may occur because the gas is forced into the cervical or endometrial vasculature.15

PRETREATMENT SERUM MARKER EVALUATION

Physicians treating many different types of cancer use serum markers to evaluate the likelihood of metastasis preoperatively. These markers are also used postoperatively to evaluate for treatment success or recurrence of disease. For example, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

is elevated in colon cancer as well as mucinous ovarian cancer.1 CA19-9 is also elevated in mucinous ovarian cancer, and α-fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated in germ cell ovarian tumors.2 CA-125 is typically used for diagnosing and following therapy in ovarian cancer, but may also be helpful in the management of endometrial cancer.16

is elevated in colon cancer as well as mucinous ovarian cancer.1 CA19-9 is also elevated in mucinous ovarian cancer, and α-fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated in germ cell ovarian tumors.2 CA-125 is typically used for diagnosing and following therapy in ovarian cancer, but may also be helpful in the management of endometrial cancer.16

Several biomarkers have been studied in relation to endometrial cancer. Biomarkers can be cytokines, growth factors, angiogenesis-promoting factors, cancer antigens, apoptotic proteins, proteases, adhesion molecules, hormones, and adipokines.17 For example, the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6), CA19-9, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7 are all elevated in endometrial cancer patients.17 Some biomarkers are seemingly close in function but are found in varied degrees in endometrial cancer. An example is MMP-2, which is decreased in endometrial cancer in contrast to MMP-7, which is elevated as mentioned earlier.17 An elevated level of CA-125 is a poor prognostic factor associated with decreased survival time.17 Elevations of CA15-3 and CA19-9 also predict a shorter survival time in patients with endometrial cancer.

Preoperative CA-125 has been proposed as a helpful measure in determining whether a patient will need full lymphadenectomy in the surgical treatment of endometrial cancer or if simple hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy will suffice.16 An elevated CA-125 is found in up to 67% of patients with advanced-stage endometrial carcinoma and is thus more likely to be elevated in patients with extrauterine and lymph node disease.16 For evaluation of recurrent endometrial cancer, distant metastatic disease is associated with elevated CA-125. Unfortunately, any method that may cause peritoneal irritation (e.g., pelvic radiotherapy for a local recurrence or diverticulitis) may artificially elevate CA-125, lowering the sensitivity of this widely used test.16

A 2001 Taiwanese study evaluated the preoperative CA-125 values of 124 patients who underwent surgical staging. Their evidence indicates a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 81% using a CA-125 value of 40 U/mL in screening for lymph node metastasis.16 In the same study, they noted the median CA-125 value was sixfold higher for stage IV endometrial cancer in comparison with stage I cancer.16 CA-125 was also noted to be elevated with positive peritoneal washings, adnexal involvement, and distant metastasis and with higher risk histologic types.16 The study also noted higher levels of preoperative CA-125 with superficial myometrial invasion as opposed to cancer confined to the endometrium. They concluded that full lymphadenectomy should be performed if preoperative CA-125 is greater than 40 U/mL.16

Recently, there has been an attempt to develop a multimarker panel to facilitate diagnosis of endometrial cancer.17 In this study, the authors found that prolactin was the most important biomarker for endometrial cancer.17 Sensitivity was 98.3% and specificity was 98% when prolactin elevation alone was used for diagnosis.17 The investigators also measured CA-125, CA15-3, and CEA, noting that these markers were more likely to be elevated in women with stage III or IV endometrial cancer possibly because later stage tumors stimulate cancer antigen shedding.17 They also found differences in biomarkers for grade 3 tumors, reporting that CA-125, AFP, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) were higher with increasing grade of tumor.17 The study also reported that a combination of prolactin, growth hormone, eotaxin, E-selectin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was helpful in distinguishing endometrial cancer from ovarian cancer and breast cancer.17

Prolactin is produced by the endometrial stromal cells during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle.17 Tumor growth could trigger stromal cell prolactin secretion.17 Prolactin has also been implicated in promotion of angiogenesis.17 Prolactin is at least twice as sensitive in diagnosing endometrial cancer as other biomarker studied by Yurkovetsky et al.17

Prolactin was accurate in 93.8% of patients with stage I, 85.8% of patients with stage II, and 96.2% of patients with stage III endometrial cancer.17 Prolactin levels were compared in patients with endometrial, ovarian, and breast cancers. Prolactin alone could not distinguish these cancers, but in conjunction with eotaxin, growth hormone, E-selectin, and TSH, it was significantly accurate and selective.17

Prolactin was accurate in 93.8% of patients with stage I, 85.8% of patients with stage II, and 96.2% of patients with stage III endometrial cancer.17 Prolactin levels were compared in patients with endometrial, ovarian, and breast cancers. Prolactin alone could not distinguish these cancers, but in conjunction with eotaxin, growth hormone, E-selectin, and TSH, it was significantly accurate and selective.17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree