Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Pathology of Penile Cancer

Alcides Chaux

Antonio L. Cubilla

GENERAL FEATURES

Most penile cancers originate in the squamous mucosal epithelia covering glans, coronal sulcus, and inner preputial surfaces (1). Tumors originating in the outer penile skin are vanishingly unusual (2). Conventional squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the prevalent histological type, but several other distinctive morphological subtypes are described (3,4). Precancerous epithelial changes are frequently observed, mainly in the squamous epithelium adjacent to invasive tumors but also as isolated lesions. The former presentation is more common in geographical areas of high incidence of penile cancer and the later in nonendemic areas for penile cancer (5). Other primary malignant epithelial, soft tissue, or lymphoid tumors are extremely rare. The penis can also be the site for metastatic tumors. A simplified and updated pathological classification of penile tumors is shown in Table 46.1.

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Epidemiology

There is a worldwide variation in the age-standardized rate (ASR) of penile cancer with geographical regions of low incidence (ASR ≤ 1.0), such as the United States, Canada, and Europe, and countries with high incidence (ASR ≥ 2.0), such as Paraguay, Brazil, Uganda, and Thailand (6,7). Several studies have also noted differences in tumor stage, metastatic rate, and cancer-specific mortality between patients from low- and high-incidence geographical areas and among individuals from different ethnic/racial groups, socioeconomic status, and religious beliefs (6,8). The disease is rare before the age of 40 and exceedingly uncommon in adolescents and children.

Several risk factors have been identified (8). The most important is phimosis, a condition characterized by incapacity to fully retract the foreskin, which is present in more than half of cancer patients. A substantially increased risk for penile cancer is observed in phimotic patients (8,9). Smoking has been related to penile cancer. There is a dose-dependent association between cigarettes consumed and penile cancer, probably related to the presence of systemic carcinogenic metabolites (8). About 40% of penile carcinomas show evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA, especially high-risk genotypes such as HPV-16, and there is a striking correlation of morphological subtypes of carcinomas showing warty and/or basaloid features and the presence of the virus (8,10). A third to one half of penile carcinomas are associated with lichen sclerosus, and there is compelling evidence indicating that this condition is specifically associated with some subtypes of cancer (usual, verrucous, papillary, and pseudohyperplastic carcinomas) (11). In addition, patients with lichen sclerosus are usually phimotic. Finally, several studies suggest that the presence of chronic inflammation, abrasions and tears, a history of genital warts, and the use of psoralen and ultraviolet A photochemotherapy represent risk factors for the development of penile cancer (8).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

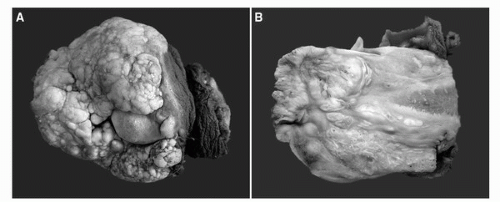

Most patients with penile SCC are in their fifties and the peak age incidence is between 50 and 70 years (3). There is a correlation between patients’ age and tumor subtype. Younger patients (around 50 years) are those with basaloid and warty carcinomas. Older patients (around 70 years) are those with verrucous and pseudohyperplastic carcinomas. The majority of tumors originate in the epithelium covering glans, coronal sulcus, and inner foreskin (3,4). Primary tumors of the shaft are extremely infrequent. The glans is the most commonly affected anatomical site (80%), followed by inner foreskin (15%) and coronal sulcus (5%). In regions of high incidence tumors are locally advanced, affecting multiple compartments in up to one half of the cases and precluding the identification of the exact site of origin. A painless tumor mass, which can be exophytic, ulcerated, or both, is the most frequent complaint (Fig. 46.1). Pain, bleeding, and dysuria are uncommon findings. Phimosis is identified in up to one half of patients, especially in those with long foreskins (9). Some patients present with advanced local disease, with extensive ulceration, scrotal and pubic involvement, satellite skin nodules, and groin metastasis. In very rare occasions, an occult (concealed by phimosis) small penile carcinoma presents as metastatic disease, usually in the groin area. Widespread dissemination may be associated with hypercalcemia and arrhythmias (12).

Pathological Features

Precancerous Lesions

There has been much confusion regarding the nomenclature and morphological features of penile precancerous lesions. Terms such as Bowen’s disease, carcinoma in situ, squamous intraepithelial lesion of low/high grade, penile intraepithelial

neoplasia (PeIN) low/high grade, and erythroplasia of Queyrat have been used. We are presenting a recently described nomenclature, PeIN, based on cell morphology, cell differentiation, association with invasive cancer, and presence or absence of HPV (13) (Table 46.2).

neoplasia (PeIN) low/high grade, and erythroplasia of Queyrat have been used. We are presenting a recently described nomenclature, PeIN, based on cell morphology, cell differentiation, association with invasive cancer, and presence or absence of HPV (13) (Table 46.2).

TABLE 46.1 CLASSIFICATION OF PENILE MALIGNANT TUMORS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

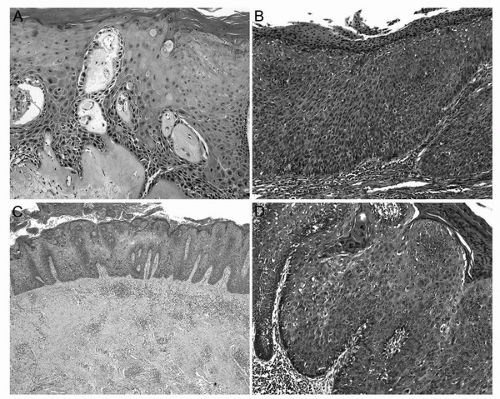

The typical gross morphology of PeIN is variegated. It usually presents as a flat to slightly raised, pearly whitish to reddish area with irregular borders. In some cases, pigmented papules, erythematous plaques, or ulceration might be seen. PeIN is microscopically classified into four types: differentiated (“simplex”), basaloid, warty, and warty-basaloid. Differentiated PeIN shows hyperkeratosis, acanthosis with cytological atypia (usually more prominent at bottom layers) and squamous maturation, well-defined cellular borders, evident intercellular bridges, and elongated rete ridges (Fig. 46.2A). In basaloid PeIN, the epithelium is replaced with a monotonous population of small to intermediate-sized cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm, indistinctive cellular borders, and high mitotic/apoptotic rate. Surface is usually flat and parakeratosis is frequently seen (Fig. 46.2B). The epithelium in warty PeIN ranges from spiky to papillary with parakeratosis, and atypical squamous cells with conspicuous koilocytosis (Fig. 46.2C). In warty-basaloid PeIN, the two previously mentioned patterns coexist with basaloid cells at the bottom and warty features at the epithelial surface (Fig. 46.2D). There is a striking correspondence between the morphologies of PeIN and the corresponding invasive SCC subtypes (13). Differentiated PeIN is associated with usual and other keratinizing SCC variants such as verrucous and papillary NOS, whereas PeIN with warty and/or basaloid features are found more frequently in invasive basaloid or warty carcinomas.

FIGURE 46.1. Gross features of penile carcinomas. (A) Exophytic verruciform warty (condylomatous) carcinoma with a typical cobblestone appearance, mainly affecting inner foreskin, coronal sulcus, and partially sparing the glans. (B) Cut surface of a penile carcinoma with a verruciform surface and infiltration into corpus spongiosum. Tunica albuginea and corpus cavernosum are not invaded. (See color insert.) |

TABLE 46.2 CLASSIFICATION OF PEIN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is recognized by a dense linear or band-like subepithelial hyalinization with an underlying chronic inflammatory response (11). The epithelium above the lesion can be atrophic, hyperplastic, or show nuclear atypias (atypical lichen sclerosus). When precancerous changes are observed in association with lichen sclerosus, they usually show a differentiated PeIN morphology (13). Lichen sclerosus is rarely present in basaloid or warty PeIN. The types of invasive SCCs associated with lichen sclerosus are the usual, verrucous, papillary, and pseudohyperplastic carcinomas.

Subtypes of SCC

About one half of penile carcinomas are SCC of the usual type, similar to those observed in other organs (3,4). However, several other subtypes with distinctive clinicopathological and outcome features are recognized. Grossly, it is difficult to separate with accuracy the special subtypes, but some generalizations can be made. Five patterns of growth may be grossly observed: superficial spreading, vertical growth, verruciform, multicentric, and mixed (3,4). Superficial spreading tumors extend horizontally through glans, coronal sulcus, or foreskin, sometimes affecting more than one anatomical compartment but with limited invasion of lamina

propria or superficial corpus spongiosum. The majority of superficial spreading patterns are observed in usual SCCs. Tumors with a vertical growth pattern frequently invade into deep penile erectile tissues; extensive ulceration is a common finding. Typically, basaloid and sarcomatoid carcinomas grow in this manner. Verruciform tumors are predominantly exophytic papillomatous low-grade tumors. They may be in situ or invade superficially into lamina propria or deeply into corpora cavernosa. Verrucous, papillary NOS, condylomatous (warty), and cuniculatum carcinomas belong to this category. In some cases, two or more tumors separated by nonneoplastic mucosa are identified (multicentric tumors), either with the same or different patterns of growth, synchronously or metachronously. Pseudohyperplastic, usual and verrucous carcinomas usually depict this growth pattern. Lichen sclerosus and preputial location are characteristic features of multicentric tumors. Mixed patterns of growth can be observed, typically in the mixed or hybrid verrucous and the warty-basaloid carcinomas.

propria or superficial corpus spongiosum. The majority of superficial spreading patterns are observed in usual SCCs. Tumors with a vertical growth pattern frequently invade into deep penile erectile tissues; extensive ulceration is a common finding. Typically, basaloid and sarcomatoid carcinomas grow in this manner. Verruciform tumors are predominantly exophytic papillomatous low-grade tumors. They may be in situ or invade superficially into lamina propria or deeply into corpora cavernosa. Verrucous, papillary NOS, condylomatous (warty), and cuniculatum carcinomas belong to this category. In some cases, two or more tumors separated by nonneoplastic mucosa are identified (multicentric tumors), either with the same or different patterns of growth, synchronously or metachronously. Pseudohyperplastic, usual and verrucous carcinomas usually depict this growth pattern. Lichen sclerosus and preputial location are characteristic features of multicentric tumors. Mixed patterns of growth can be observed, typically in the mixed or hybrid verrucous and the warty-basaloid carcinomas.

FIGURE 46.2. Types of PeIN. (A) Differentiated PeIN with atypical squamous cells in the basal/parabasal layers, retained maturation and hyperkeratosis. Note the dense subepithelial colagenization band corresponding to lichen sclerosus. (B) Basaloid PeIN exhibiting a total replacement of the epithelium by a population of small and monotonous basophilic cells. Mitoses are abundant. Surface is flat and parakeratosis is evident. (C) Low-power view of a warty PeIN showing acanthosis and papillomatosis. Surface is spiky and hyperkeratotic. (D) Warty-basaloid PeIN with basaloid cells occupying one half to two thirds of the epithelial thickness and typical condylomatous changes on surface with koilocytosis, spiky surface, and prominent parakeratosis. (See color insert.) |

Usual SCC, also named classical or conventional SCC, is the most frequently found subtype, representing 48% to 65% of all penile carcinomas. It is characterized by neoplastic nests composed of polygonal cells with moderate to ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, distinctive cellular borders, and evident intercellular bridges. Most tumors are moderately differentiated, with more or less keratinization but with a clear tendency toward squamous differentiation (Fig. 46.3A). Some usual SCC harbors foci of anaplastic cells with high mitotic rate. These tumors should be considered as poorly differentiated (grade 3) regardless of the proportion of anaplastic cells (14). Verruciform tumors represent 19% to 22% of penile SCCs and include warty (condylomatous), verrucous, papillary, and cuniculatum carcinomas. Warty carcinomas are HPV-related exophytic malignant neoplasms accounting for 7% to 10% of all penile carcinomas and 34% to 36% of all verruciform tumors. They are characterized by papillomatosis, prominent fibrovascular cores, atypical parakeratosis, and jagged tumor base (15). Koilocytes, polygonal cells with

wrinkled hyperchromatic nuclei, perinuclear halos, frequent bi and multinucleation and well-defined cellular boundaries, are readily found, either in superficial papillae or in deep infiltrative nests (Fig. 46.3B). In verrucous carcinomas (3%-8% of all penile SCC and 12%-38% of all verruciform tumors) there is papillomatosis, marked hyperkeratosis, prominent acanthosis, inconspicuous or absent fibrovascular cores, and a broad pushing tumor base (Fig. 46.3C). Neoplastic cells are extremely well differentiated, intraepithelial keratin plugs are common, and koilocytes are absent. Verrucous carcinomas usually infiltrate only superficial anatomical levels. Papillary, not otherwise specified (NOS) carcinomas, representing 5%

to 15% of all penile SCC and 27% to 53% of all verruciform tumors, are characterized by papillomatosis with complex papillae, irregular fibrovascular cores, mild to moderate acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, and a jagged tumor front of invasion (Fig. 46.3D) (16). Neoplastic cells are well to moderately differentiated, and koilocytes are absent. Similar to warty SCC, papillary carcinomas tend to invade corpus spongiosum and, in occasions, corpus cavernosum. Both verrucous and papillary NOS carcinomas are tumors with a very low or null HPV detection rate (10). These malignant exophytic tumors should be distinguished from the unusual giant condyloma (Buschke-Löwenstein tumor), a benign albeit locally destructive, low-risk HPV-related penile neoplasm. Unlike verrucous carcinomas, there is surface koilocytosis and unlike warty carcinomas, the boundaries between tumor and stroma are sharply delineated. Giant condylomas of long duration are prone to malignant transformation (2).

wrinkled hyperchromatic nuclei, perinuclear halos, frequent bi and multinucleation and well-defined cellular boundaries, are readily found, either in superficial papillae or in deep infiltrative nests (Fig. 46.3B). In verrucous carcinomas (3%-8% of all penile SCC and 12%-38% of all verruciform tumors) there is papillomatosis, marked hyperkeratosis, prominent acanthosis, inconspicuous or absent fibrovascular cores, and a broad pushing tumor base (Fig. 46.3C). Neoplastic cells are extremely well differentiated, intraepithelial keratin plugs are common, and koilocytes are absent. Verrucous carcinomas usually infiltrate only superficial anatomical levels. Papillary, not otherwise specified (NOS) carcinomas, representing 5%

to 15% of all penile SCC and 27% to 53% of all verruciform tumors, are characterized by papillomatosis with complex papillae, irregular fibrovascular cores, mild to moderate acanthosis and hyperkeratosis, and a jagged tumor front of invasion (Fig. 46.3D) (16). Neoplastic cells are well to moderately differentiated, and koilocytes are absent. Similar to warty SCC, papillary carcinomas tend to invade corpus spongiosum and, in occasions, corpus cavernosum. Both verrucous and papillary NOS carcinomas are tumors with a very low or null HPV detection rate (10). These malignant exophytic tumors should be distinguished from the unusual giant condyloma (Buschke-Löwenstein tumor), a benign albeit locally destructive, low-risk HPV-related penile neoplasm. Unlike verrucous carcinomas, there is surface koilocytosis and unlike warty carcinomas, the boundaries between tumor and stroma are sharply delineated. Giant condylomas of long duration are prone to malignant transformation (2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree