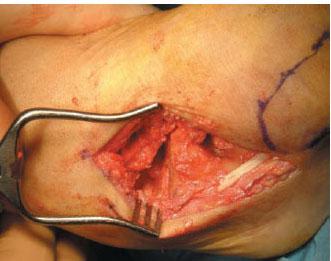

Figure 4.17 Collapse of the medial arch from Charcot neuroarthropathy creates increased plantar pressures often resulting in ulcerations.

Regardless of the procedure performed, an adjunctive TAL is usually indicated for many neuropathic patients. Lengthening the Achilles tendon decreases the amount of force transmitted to the forefoot and midfoot during the propulsive phase of gait. Ulcer excision with primary closure is also preferred and may require additional skin grafting or flaps.

EXOSTECTOMY

Indications

An exostectomy is a very simple technique to address bony prominences within the foot when offloading and conservative measures have failed. It can be very effective when used in the right circumstances. Neuropathic patients with midfoot collapse often have bony prominences causing increased pressures, resulting in callus formation and ulceration. If this deformity is rigid and stable, an exostectomy may be the best choice. Exostectomies may also be considered in the very elderly, minimally ambulatory patient when the primary goal is to close a wound quickly to prevent infection. If osteomyelitis is present, an exostectomy can be curative as well as corrective. However, if any motion or instability exists or the resection has the potential to cause instability because of its size or location, then this isolated procedure should be avoided. In this setting, a more formal deformity correction, including arthrodesis, should be considered.

Surgical Technique

INCISIONAL APPROACHES. Incision placement is influenced primarily by the depth, but also the size, location, and quality of the overlying tissues and ulcer. These four factors help determine whether to approach the exostectomy directly or indirectly. For indirect approaches, a separate skin incision is made on non–weight bearing surfaces away from the ulcer site, whereas direct approaches involve excising the ulcer and approaching the exostosis directly through this site.

Indirect approaches are typically used when the exostosis is located on the plantar-medial or plantar-lateral aspects of the foot. Incisions can be placed on the side of the foot, avoiding the non–weight-bearing surface. These approaches are reserved for more superficial ulcers that do not communicate with the bony exostosis. The overlying soft tissues should also be free of pathologic tissues and bursa formation.

Deeper ulcers or ulcers that can be excised with primary wound closure are more amenable to a direct approach, as previously discussed. If there is active infection or a history of osteomyelitis, the bone and ulcer can be directly excised. Underlying bursa tissue, even with overlying superficial granular tissue, should persuade the surgeon to opt for a direct approach for concomitant bursa excision.

OSSEOUS RESECTION. once soft tissue impediments have been removed, the actual resection of bone can occur. Various techniques are available and are dictated by exposure and shape of the bone. Planing via saw is efficient, but the blade’s excursion often limits its use. Thermal necrosis is not a concern because the goal is to prevent regrowth of the bone. However, the plantar location of these wounds often makes it very difficult to use power instrumentation; instead, a combination of standard and curved osteotomes is useful when osseous surfaces curve abruptly. The rongeur is appropriate for small prominences and shaping of residual bone. The goal of these procedures is to create a flat surface without leaving a new ridge or step-off. Following resection, a rasp should smooth the surfaces as needed. The site should be irrigated; closure may include ulcer excision, and a local flap if deemed necessary.

Postoperative Management

Drains are used if concern exists for hematoma formation, especially after resection of cancellous bone. Adequate compression over the incision, elevation, as well as immobilization of the foot is also critical. If incisions are on the weight-bearing surfaces of the foot, non–weight bearing is recommended for at least 3 weeks. However, patients typically require an average of 6 to 8 weeks without placing weight on the foot.

Complications and Outcomes

In a 1997 study, which looked at the outcomes following lateral column exostectomies, 32 feet in 31 patients underwent an exostectomy alone (n = 7), with primary closure (n = 17), or a rotational flap (n = 8). Of these, 25% required additional resection or flap coverage. The overall success rate was 89% (35). Catanzariti et al performed 27 procedures; 18 were for the treatment of medial column ulcerations, whereas the remaining nine were lateral column wounds. They reported a 74% healing rate; however, 85% of those patients who did not heal initially had lateral column ulceration. Fifty-five percent of the patients with lateral column ulcers initially required revi-sional surgery to facilitate healing. They reported a statistically significant difference in the rate of complication based on ulcer location. They concluded that the lateral column is less predictable and often requires an adjunctive soft tissue procedure to be successful (36). Pinzur et al used exostectomy in eight patients, and found that 100% were ambulatory in accommodative footwear after 3.6 years (37). Brodsky and Rouse found that 11 of 12 patients remained healed after a mean follow-up of 25 months (38).

REALIGNMENT MIDFOOT OSTEOTOMIES WITH ARTHRODESIS

Indications

When exostectomy fails, instability or motion exists or significant deformity of the midfoot has occurred secondary to Charcot neuroarthropathy, a more stabilizing aggressive approach is recommended (Fig. 4.17). Controversy exists with regard to surgical timing in neurogenic osteoarthropathy. Many practitioners had originally advocated for a delayed approach, in which reconstruction efforts were used during the remodeling phase of the Charcot process. Recently, this practice has come into question and many practitioners are choosing instead to intervene earlier. The rationale behind this change focuses on the neurotraumatic theory of Charcot joint formation. Assuming that an initial Charcot episode presents to the clinic, treatment begins by approaching the event as an acute fracture. offloading techniques are used until both edema and erythema are controlled. once this has stabilized, usually within 5 to 7 days, an aggressive reconstructive approach centered on arthrodesis and deformity correction is employed. With this approach, we believe that we can prevent more severe deformities from occurring by stabilizing the foot in the initial phases. At our institution, we have found a high degree of success with this approach, but a formal analysis of outcomes has yet to be performed. Publication of our results is planned once a larger number of patients have achieved longer follow-up.

Surgical Technique

SURGICAL PLANNING. Typically, the apex of the deformity is first identified. second, it is determined if the deformity exists in either one or a combination of transverse, sagittal, or frontal planes. At this point, multiple options are available to the surgeon. The decision whether to perform acute or gradual correction is determined. If acute correction will not compromise the neurovascular structures and there is adequate soft tissue for primary closure, acute correction is preferred. Options for acute correction include single or multiplane midfoot realignment osteotomies via closing or opening wedge arthrodeses, removal of bone wedges, and removal of entire extruded midfoot bones.

Attention to restoring normal or “more normal” anatomy is important. It is not recommended to fuse the foot in its current position. If reduction is difficult, removal of bone, joint releases, and assisted external fixation distraction can be very helpful.

It is also important to remember that Charcot does not typically involve only the medial or lateral column, but occurs transversely through an entire section of the foot (Fig. 4.18).

Figure 4.18 Charcot neuroarthropathy occurs transversely across the entire foot. Therefore, the entire foot should be surgically addressed.

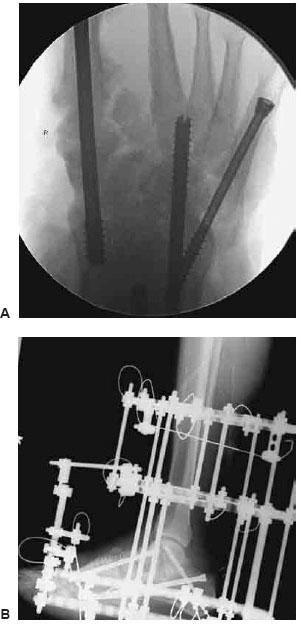

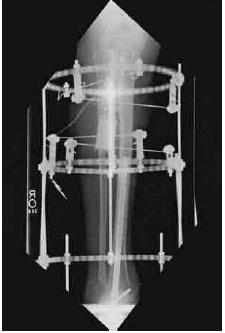

Because of this, the entire foot must be addressed. Even if the deformity primarily involves one joint or one column, both the medial and lateral columns need to be addressed for long-term stability and success. Arthrodesis of isolated joints is no longer recommended because of failure rates and the progressive nature of this condition (Fig. 4.19A–C). Instead, more aggressive fusion techniques and hardware configurations are being employed. In addition, by fusing additional joints proximal and distal to the Charcot deformity, the threads of the screws pass beyond the pathologic bone, thus improving stability and compression across the surgical site (Philip Basile, personal communication) (Fig. 20A,B).

SINGLE PLANE REALIGNMENT OSTEOTOMIES WITH ARTHRODESIS. Midfoot Charcot neuroarthropathy may only involve deformity within one plane. If this is present, it is typically a midfoot collapse in the sagittal plane without abduction of the forefoot. It is less common to have only a transverse plane deformity without sagittal collapse. If deformity is within only the sagittal plane, a single complete medial to lateral osteotomy through the midfoot with manipulation can achieve correction. However, if there is an isolated transverse plane deformity, opening or closing wedge osteotomies are usually necessary. If a single osteotomy was employed to correct an abducted or adducted midfoot deformity, translation of the forefoot medially or laterally, respectively, would create additional bony prominences and problems.

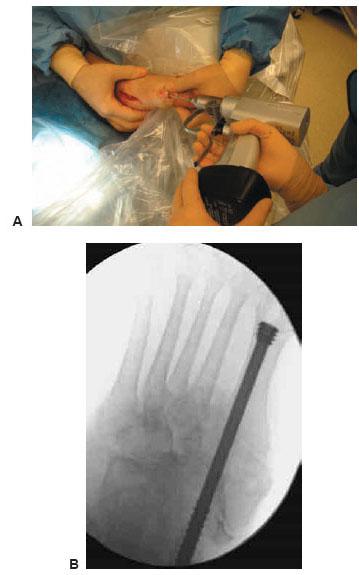

Incisional Approaches. This single plane correction lends itself to either an open or more minimally invasive approach. If more formal joint preparations are desired or wedges of bone are to be removed or added, curvilinear incisions are placed on the medial and/or lateral aspects of the midfoot, centered over the joints that are to be fused. However, it is possible to perform the osteotomy without direct visualization with the use of fluoroscopy and a Gigli saw in sagittal single plane deformaties (39) (Fig. 4.21). If it is elected to perform this percutaneously, small incisions placed directly over joints allow a small burr or osteotome to gain access for joint preparation.

Surgical Technique. Following soft tissue dissection, the dorsal and plantar soft tissue structures should be bluntly reflected from the bone. If desired, K-wires may be driven transversely across the deformity apex under fluoroscopy to use as a guide for the osteotomy (Fig. 4.22). If a wedge of bone is to be removed, two converging K-wires can be used to facilitate accuracy of wedge resection cuts.

Figure 4.19 Charcot deformity correction requires additional larger and longer hardware involving stabilization of the entire foot to avoid failure. A. Hardware failure from progression of Charcot following an isolated metatarsal-cuneiform arthrodesis. B. Loss of correction following an isolated talar-navicular arthrodesis. C. Proximal progressive Charcot following an isolated fusion resulting in complete destruction of the talus requiring subsequent tibial-calcaneal, medial, and lateral column arthrodeses.

Figure 4.20 When dealing with midfoot Charcot, additional joints both distal and proximal to the pathologic bone should be included into the surgical planning along with additional larger fixation for long-term success and stability. A. Example of a combination of multiple intra-medullary roddings. B. This fixation was further backed up with a static circular external fixation device. (Courtesy of Barry Rosenblum and Philip Basile.)

If the problem lies within only the sagittal plane, often bone wedges do not need to be removed. Instead, a through-and-through single osteotomy directed transversely across the apex of the deformity can be used. This can be performed with the use of a power saw, osteotome or Gigli saw, depending on surgeon’s preference. The soft tissue structures, both dorsally and plantarly, must be protected and the surgeon’s free hand can be placed on the dorsum of the foot to help use tactile vibratory responses to prevent overzealous dorsal blade displacement. It is recommended that the surgeon performs an incomplete osteotomy dorsally. The bone resection is then completed with an osteotome or osteoclasis via manipulation to ensure safety of the dorsal neurovascular structures.

Figure 4.21 In patients with absolute contraindications to tourniquets and are on anticoagulants because of recent vascular bypasses, a minimally invasive midfoot osteotomy via Gigli saw technique may be advantageous. (Courtesy of Philip Basile.)

Once the transverse midfoot osteotomy is complete, the foot can be manipulated into position easily. The joints are prepared for fusion based on surgeon’s preference. This may be done by curettage, osteotomes, rongeurs, burrs, or other modalities. The forefoot is then plantarflexed until the bisection of the talus is collinear with the bisection of the first metatarsal. Guide wires or temporary K-wires are then used to hold the osteotomy in place for fixation.

MULTI-PLANE REALIGNMENT OSTEOTOMIES WITH ARTHRODESIS. More commonly, Charcot neuroarthropathy involves both sagittal and transverse plane deformities. These types of deformities may be corrected with either biplanar closing or opening wedge osteotomies.

Figure 4.22 A transverse K-wire may be transversely driven across the apex of the deformity to serve as a guide for the osteotomy.

Incision. Because wedges of bone are either being removed or added to osteotomies or joint fusion sites, it is more challenging to use minimally invasive approaches in this situation. Curvilinear incisions are placed directly over the medial and lateral columns. The medial incision typically extends from the talus to the medial first metatarsal-cuneiform joint, with care being taken to be centered directly over the medial column. The lateral incision is similar to the incision described for a triple arthrodesis and can be extended proximally if access to the subtalar joint is desired.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Closing Wedge Osteotomies. Closing wedge osteotomies involve removing a large biplanar wedge of bone at the apex of the deformity (Fig. 4.23). If the deformity involves sagittal midfoot collapse and abduction, more bone will be removed plantarly and medially. However, if there is midfoot collapse and forefoot adduction, a plantar lateral wedge of bone is removed. A similar technique to the single plane wedge removal is employed, except that the correction is biplanar. Converging K-wires are placed transversely under fluoroscopy as a guide for wedge resection. The dorsal and plantar soft tissues are protected and the wedge resections are performed. The bone is removed and the foot can then be manipulated into place. sometimes, additional reciprocal planing is useful to improve realignment and bony apposition.

OPENING WEDGE OSTEOTOMIES. Opening wedge osteotomies are more commonly used in the severely abducted foot and are more frequently thought of as lateral column lengthenings. Bone allograft has been shown to be successful (40) and is often chosen over autograft to minimize donor site morbidity. Tricortical iliac crest allograft usually works well. The only exception is when large noninfected bone resections are removed from one area, such as the medial column, and can be placed in another area, such as the lateral column. Even then, additional allograft may be necessary to achieve enough deformity correction. Bone allograft also may be placed dorsally in the osteotomy or joint fusion space to plantarflex the forefoot (Fig. 4.24). Conversely, allograft can be placed medially to abduct a foot, or plantarly to dorsiflex the forefoot. The use of a temporary monorail may sometimes be used to distract and open the area to help achieve correction in more severe deformities.

Figure 4.23 Example of a biplanar wedge resection in midfoot closing wedge arthrodeses

Figure 4.24 Example of an opening wedge arthrodesis with an allograft wedge placed dorsally to plantarflex the forefoot. (Courtesy of Barry Rosenblum.)

If frontal plane deformity coexists, the forefoot can also be rotated through the osteotomy site to either increase pronation or supination. To maintain bony apposition, additional reciprocal planing may be necessary with this technique. Guide wires or temporary K-wires are then used to hold the correction in place for fixation.

POSITIONING AND FIXATION TECHNIQUES. Whether single osteotomies, opening or closing wedge arthrodeses are employed, the ultimate goal is to achieve a stable, plantigrade foot with good alignment, thus preventing skin breakdown and future ulcerations. First, alignment of the rearfoot to the leg and then to the forefoot should be assessed. The longitudinal bisection of the talus should be as close to collinear as possible to the bisection of the first metatarsal on the sagittal and anterior-posterior views. This is very important because undercorrection of a collapsed medial arch does not correct the initial problem, and an over- plantarflexed medial column can lead to first metatarsal head ulcerations in neuropathic patients. other important intraoperative angular measurements to consider include the metatarsus adductus angle, talocalcaneal angle, and the cuboid abduction angle. The metatarsus adductus angle (normal: 0–15 degrees) is measured from the anterior-posterior views and helps evaluate the transverse position of the forefoot to the rearfoot. The cuboid abduction angle (normal: 0–5 degrees) also evaluates the transverse correction and is particularly important when ensuring adequate correction of abduction deformities. Finally, the talocalcaneal angle (Kite’s Angle) (normal: 15–35 degrees), is primarily used to evaluate frontal plane correction. This angle increases with pronation and decreases with subtalar joint supination.

Once proper alignment of the midfoot correction has been achieved, a number of different fixation modalities have been effective. As stated, even if the deformity involves mainly one joint or column, both medial and lateral columns are typically addressed. Additional and larger fixation in neuropathic patients is also recommended with fusion extending both proximally and distally past the pathologic bone. A subtalar arthrodesis is frequently included for a midfoot correction.

Fixation first begins by addressing the realigned primary deforming force. Because a collapsed medial arch is often the most common and severe aspect of these deformities, fixation of the medial column is often addressed first. Achieving collinearity of the talus and first metatarsal is stressed and often requires a more extended fusion of the medial column. Whether screws, staples, plates, wires, pins, or external fixation is used, it is important to have compression, strength, and stability across the fusion sites. It is common to use additional fixation, fuse additional joints, and increase the fixation device by size and length from baseline when dealing with neuropathic patients.

Rodding Techniques. Medial column roddinghas been shown to be a very successful fixation device in this situation (41–43). Its function is more analogous to an intramedullary nail procedure that helps resists cantilever bending forces. It also ensures complete realignment and collinearity of the first metatarsal to the talus with preservation of cortical integrity. Fixation and compression are directly perpendicular to the joints being fused. Finally, medial column rodding procedures reduce soft tissue and bone trauma and are not prominent. Disadvantages are that it requires damage to the cartilage of the first metatarsal head; however, this is less of a concern in neuropathic patients. The screw may back out or break, which is why it is critical to use a larger screw, such as an 8-mm diameter dual threaded screw (43).

Figure 4.25 A. A guidewire is advanced from the first metatarsal head through the medial column and ending in the talus while the foot is held in a corrected position. B. Once correction and wire placement is confirmed under the image intensifier, an 8-mm dual threaded screw is advanced over the guidewire.

The first MPJ is exposed through a limited dorsal incision and a guidewire is advanced under fluoroscopy through the first metatarsal, medial cuneiform, navicular, and into the talus, while holding the foot into a corrected position. Alternatively, the correction may be stabilized with strategically placed K-wires that do not interfere with screw placement. The image intensifier must be used to ensure adequate reduction of the deformity and central placement of this wire on both anterior-posterior and lateral views. Once this had been achieved, a large dual threaded 8-mm partially threaded cannulated screw is placed over this wire and advanced until the threads are completely within the body of the talus and the head of the screw is seated below the joint surface into the metaphyseal aspect of the first metatarsal head (Fig. 4.25A,B). The advantage of a dual-threaded screw is that the threaded head and tip are seated completely within the first metatarsal head and talus, respectively. This achieves compression and stabilization across the entire medial column when the threads compress the cancellous bone of the first metatarsal head and body of the talus together.

As mentioned, medial column fusions are typically accompanied by lateral column stabilizing procedures in midfoot Charcot neuroarthropathy. Lateral column rodding is a very solid technique to achieve this goal. First, it is determined which lesser metatarsal (third, fourth, or fifth) is the most collinear with the cuboid. This MPJ is exposed through a minimal dorsal incision, and a long guidewire is advanced under fluoroscopy through the lesser metatarsal, cuboid, and calcaneus. Once adequate deformity reduction and wire alignment have been achieved, this wire is retrograded through the entire calcaneus and posteriorly through the skin. A large dual threaded 8-mm partially threaded cannu-lated screw is then placed over this wire and advanced from the calcaneus and into the cuboid and base of the lesser metatarsal (Philip Basile, personal communication) (Fig. 4.26).

Circular External Fixation. Circular external fixation has been used alone or in combination with internal fixation for correction of these midfoot deformities. Because acute correction has already been achieved, the external fixation device is used as a static construct in this situation. When used in combination, the construct helps back up the internal fixation by helping to eliminate deforming forces while the fusion consolidates. Two tibial rings and a foot plate below help provide additional stability. An additional contact ring below the foot plate allows for attachment of a shoe tread.

Figure 4.26 Example of a lateral column rodding extending from the calcaneus, through the cuboid and ending with the threads in the fourth metatarsal base. Additional intramedullary roddings may be added with subtalar joint fusion and circular external fixation as depicted in Figure 4.20A,B. (Courtesy of Philip Basile.)

Postoperative Management

Drains are used if there is concern for hematoma formation postoperatively. The patient is kept non–weight bearing and immobilized with compression either in a posterior splint, or protective below-the-knee cast. Serial radiographs are obtained and patients are transitioned to partial weight bearing in the frame or below-the-knee cast or brace once signs of trabeculation appear. Partial weight bearing most commonly begins by the eighth week with full weight bearing by week 12. Patients should be kept in either a protective cast or below-the-knee brace until an appropriate brace or accommodative shoe gear is constructed.

Complications and Outcomes

Complications should be anticipated and handled quickly. Wound healing problems frequently occur. Other complications may include but are not limited to nonunions, delayed unions, malunions, infections, hardware complications, reul-cerations, pin track infections, and postoperative edema.

REARFOOT

Elective rearfoot surgery is undertaken when one or a combination of the following goals needs to be achieved: stability, realignment of the rearfoot to the leg and midfoot, and prevention of infection and subsequent amputation from skin breakdown or ulceration.

Instability in combination with malalignment is often the primary underlying cause of chronic ulcerations. This combination can have devastating consequences, leading to skin breakdown, infection, and eventual amputation. Although the risk of surgical complications is greater when the primary deformity is more proximal, so is the risk of amputation when conservative measures fail. Bracing and customized shoes are often a challenge. When conservative measures cannot heal a chronic ulceration, aggressive surgical intervention may prevent limb amputation and an unnecessary course of prolonged non–weight bearing and patient deconditioning. The severity of these problems usually requires some form of arthrodesis procedure.

TRIPLE ARTHRODESIS

Indications

Triple arthrodesis can be a powerful procedure, achieving all the goals of rearfoot surgery in the neuropathic patient: stability, realignment of the rearfoot to the leg and midfoot, and prevention of infection from skin breakdown secondary to deformity. It is usually performed in combination with a TAL for many neuropathic patients. Lengthening the Achilles tendon first helps mobilize the calcaneus to aid in correction as well as decrease the amount of propulsive forces transmitted to the forefoot following fusion of these joints (Fig. 4.27). In addition, a modified triple arthrodesis is sometimes necessary in neuropathic patients, especially in the setting of Charcot neuroarthropathy. By fusing additional joints, screw purchase and stability improve because the threads of the screws are bypassing the pathologic bone (Fig. 4.20B).

Figure 4.27 Example of equinus deformity creating increased forefoot and midfoot pressures and deformity.

Surgical Technique

INCISION. Following the TAL, the triple arthrodesis classically begins with a lateral incision that starts just inferior to the lateral malleolus and ends at the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsals. Excellent exposure of the calcaneal-cuboid and subtalar joints can be obtained through this approach. The lateral aspect of the talonavicular joint also may be visualized, but a second medial incision is often required to gain full access to this joint, especially with an abducted foot. Exposure is obtained in layered dissection, reflecting the extensor digitorum brevis superiorly and peroneal tendons inferiorly. It is sometimes necessary to resect the calcaneal-fibular ligament to gain access to the subtalar joint; therefore, it should be repaired at the conclusion of the case to avoid future lateral ankle instability.

The medial incision begins just anterior to the medial malle-olus and curves over the talonavicular joint, ending at the inferior aspect of the navicular-cuneiform joint. This incision can be extended distally if additional medial column joints require formal fusion. Complete visualization of the talonavicular joint as well as the dorsal talar neck can be achieved through this incision (44).

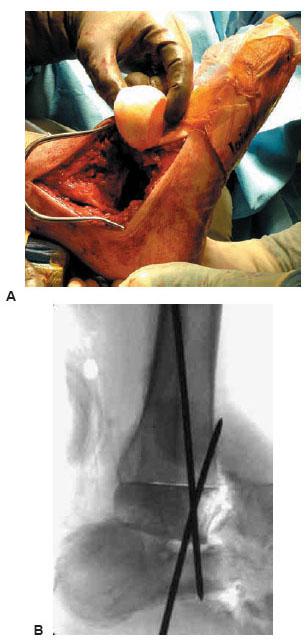

JOINT PREPARATION. With the calcaneal-cuboid, subtalar, and talar-navicular joints exposed, the surgeon may use the method of choice to remove the cartilaginous surfaces. If wedges of bone are removed to correct bony malalignment, a power saw or osteotome may be used, but care must be taken to avoid thermal necrosis. Wedging procedures can be very effective in correcting all planes of deformities. Alternatively, if shortening prohibits wedging, a curettage technique may be employed. This preserves bony contours and prevents loss of foot height that may sometimes cause shoe irritation from the malleoli postoperatively. Regardless of the technique, all cartilage is denuded and the bone surfaces are fenestrated with a K-wire or shingled with a small osteotome to promote subchondral bleeding.

Malalignments can also be corrected with interpositional bone allografts. An interpositional allograft placed within the subtalar joint can help correct varus or valgus deformities. Allograft is also frequently interposed between the calcaneus and cuboid to lengthen the lateral column in severely abducted feet. Sliding of the tarsal bones can also be used to alter arch height, but can be difficult to perform if the deformity is very rigid.

POSITIONING. Whether wedging, sliding or interpositional grafting is performed, preservation of bone contours is employed. The ultimate goal is to achieve good alignment, thus preventing skin breakdown and future ulcerations. First, alignment of the rearfoot to the leg should be assessed. The heel is best evaluated from a posterior orientation and should be rectus to slightly everted in relation to the leg. In the sagittal plane, the calcaneal inclination angle should be 15 to 20 degrees and the lateral process of the talus should bisect the longitudinal axis of the tibia. Finally, the foot should be placed in 10 to 15 degrees of abduction in the transverse plane. With the rearfoot now aligned to the leg, the forefoot–rearfoot relationship should be assessed. The subtalar joint is placed in 5 to 10 degrees of valgus, with the talar-calcaneal angle 15 to 35 degrees. The longitudinal bisection of the talus should be as close to collinear as possible to the first metatarsal on the sagittal plane views.

FlXATION TECHNIQUES. Once proper alignment of the triple arthrodesis has been achieved, a number of different fixation modalities have been effective. Traditionally, the subtalar joint is fixed first, however, in severe deformity correction; the fixation order may need to be altered. Particularly in the setting of Charcot, our institution advocates fixation across the joint with the primary deformity first. Because a collapsed medial arch is often the most severe aspect of these deformities, fixation of the medial column is often addressed initially. Achieving collinearity of the talus and first metatarsal is stressed and sometimes requires a more extended fusion of the medial column. Furthermore, like midfoot arthrodeses, it is our institution’s experience that it is necessary to use more fixation and larger fixation than what is traditionally used in non-neuropathic patients. Whether screws, staples, plates, wires, pins, or external fixation is used, it is important to have compression, strength, and stability across the fusion sites.

Postoperative Management

If necessary, closed suction drains are used to prevent hematoma formation and the incisions are closed in a layered fashion. The foot is dressed with a dry sterile dressing and a compressive posterior splint is applied to the leg. The patient is kept non–weight bearing with elevation and once the drain is removed and edema controlled, a below-the-knee fiberglass cast is applied. It is important to cast only after swelling has gone down, as severe wound problems can occur from cast irritation in neuropathic patients. If concern exists, a bivalve cast may be applied until the surgeon is comfortable placing the patient in an enclosed fiberglass cast. Sutures may need to remain in for up to 3 to 4 weeks and the patient is kept immobilized and non-weight bearing until radiographs demonstrate evidence of consolidation. Typically, the patients are progressed to partial weight bearing at 6 to 8 weeks with fullweight bearing in a below-the-knee walking boot or cast at 10 to 12 weeks. Physical therapy is frequently needed during the postoperative period because of activity adjustments and deconditioning.

COMPLICATIONS AND OUTCOMES. Wound healing problems in this patient population are essentially expected, but with proper débridement and wound care, are seldom an issue. Other complications include but are not limited to postoperative infection, edema, nonunions, delayed unions, malunions, and hardware complications.

REALIGNMENT CALCANEAL OSTEOTOMIES

Realignment calcaneal osteotomies are an effective and powerful way to realign the rearfoot to the leg. These may be isolated procedures or can be built into a fusion procedure, depending on the situation (45). Two procedures that are commonly used in neuropathic patients are the Evans and posterior calcaneal displacement osteotomy.

Lateral Column Lengthening

Evans lateral column lengthening can achieve triplanar correction when there is primarily forefoot abduction combined with some valgus deformity and sagittal collapse. Although lateral column lengthening is traditionally recommended for flexible deformities, it can be built into triple arthrodesis procedures as well by lengthening through the calcaneal cuboid fusion. The lateral column lengthening swings the forefoot out of abduction and concomitantly tightens the peroneus longus. This indirectly increases arch height by plantarflexing the first ray, and supination of the subtalar joint is also achieved. A concomitant medial column arthrodesis or plantarflexory osteotomy may be necessary to achieve balance and avoid new areas of preulcerative lesions in neuropathic patients (46).

Posterior Calcaneal Displacement Osteotomy

When dealing with primarily frontal plane valgus deformities, a posterior calcaneal displacement osteotomy (PCDO) or Koutsogiannis osteotomy may be beneficial. Like the Evans, this procedure is also typically recommended for flexible deformities without arthritic rearfoot changes. However, this osteotomy may be used in conjunction with subtalar or triple arthrodesis. In fact, this is preferred over trying to obtain frontal plane correction through the subtalar fusion site with bone resection and/or allograft wedges. Correcting frontal plane deformities through subtalar fusion site can be very difficult and technically demanding because of its shape. Instead, a PCDO may be done in addition to the planned subtalar fusion with two large screws capturing both the osteotomy and STJ fusion site (Fig. 4.28). It is also recommended to bevel and smooth the prominent cortical shelf after medial translation of the calcaneus. Any remaining bony prominence can lead to future ulceration in neuropathic patients.

Figure 4.28 Calcaneal osteotomies may be used to correct frontal plane malalignment in conjunction with a subtalar joint arthrodesis. (Courtesy of Philip Basile.)

OTHER REARFOOT AND ANKLE ARTHRODESES

Other triple-like variations may be required depending on the amount and location of deformity. More extensive fusions such as a pan-talar fusion or a rodding of the entire medial and lateral column may be necessary. When malalignment or significant instability of the ankle joint exists to the point that there are preulcerative regions or ulcerations with bracing, it should be fused in neuropathic patients. Multiple studies have evidenced that Charcot deformity of the ankle, which accounts for 5% of the patterns, can have the most devastating results (47–49). The goals of surgery and indications are similar to the triple arthrodesis. However, it can not be emphasized enough that positioning of the joints is critical and malalignment can cause problems that are worse than the original deformity. It is also important to remember to evaluate the entire extremity. The location of the primary deformity must be determined and more proximal mal-alignments should be addressed first.

TIBIAL-CALCANEAL ARTHRODESIS FOLLOWING TALECTOMY

Indications

It is important to address the talus and determine its overall integrity. Neuropathic patients with severe malalignment may be ambulating directly on a malleolus or a portion of the talus (Fig. 4.29). Sometimes the talus may not be salvageable if it has had osteomyelitis, avascular necrosis, or destruction from Charcot neuroarthropathy. The role of the talectomy traditionally has been reserved for residual pediatric deformities, but is also indicated in this situation (50–55). Prior to reconstructive surgery, resolution of infection and wound closure should be attempted. This may require off-loading techniques, staged débridements with antibiotic beads, skin grafts, and flaps.

Figure 4.29 Ankle Charcot is often unstable and progressive requiring major arthrodeses procedures. This is an example of a medially subluxed talus in which a neuropathic patient was ambulating on.

Surgical Technique

Surgical technique is demanding, and attention to alignment with respect to the entire limb is critical. Complications should be expected and treated early. The tibial-calcaneal fusion can be performed in the supine position with the limb draped proximal to the knee and patella forward for proper alignment planning. A transfibular lateral approach allows excellent exposure for talectomy and preparation of the articular surfaces.

Proper alignment with good apposition of bony surfaces is critical for long-term success. Direct contact between the calcaneus to the tibial plafond without remodeling or en bloc bone graft will result in an iatrogenic calcaneal gait position because of the angulation of the calcaneal posterior facet. To avoid this, femoral head allograft fashioned intraoperatively has been utilized for our group to achieve good apposition, deformity correction, and minimization of leg length discrepancies (56, Philip Basile, personal communication) (Fig. 4.30A,B). The final foot position should be in neutral sagittal plane position to the leg, 0 to 5 degrees of frontal plane valgus, 5 to 10 degrees of external rotation, and slight medial and posterior translation of the foot. This step in the procedure is the most time consuming but is necessary for success.

Figure 4.30 A,B. Following talectomy, allograft can be used to maintain proper positioning of the rearfoot to the leg to avoid a calcaneal gait following arthrodesis. (Photographs courtesy of Philip Basile.)

Figure 4.31 Example of circular external fixation over retrograde intramedullary nailing for tibiocalcaneal arthrodesis following talectomy.

FIXATION TECHNIQUES. A variety of fixation techniques have been described including screws (57,58), Steinmann pins (59), plates (60–62), external fixation (63–65), and intramedullary nailing (66). Each modality has its advantages and disadvantages; there is no consensus on the best method of fixation.

Our institution advocates use of a circular external fixation device over a retrograde intramedullary nail (IMN) when facing tibial-calcaneal arthrodesis following talectomy in neuropathic patients (Fig. 4.31). With regard to strength and stiffness, IMNs have been found to be significantly stiffer in all bending and torsional directions compared with crossed lag screws (67,68). Recent literature has also demonstrated that uniplanar IMNs were equivalent to blade plates but have the advantage of less dissection, do not rely as much on bone mass or quality, and can be dynamically locked (69). The external fixator is also minimally invasive and acts as an additional stabilizing force. This load-sharing combination allows for a quicker transition to protected weight bearing as the frame helps to eliminate damaging forces and promotes coaxial weight bearing through the fusion site.

Postoperative Management

Serial radiographs are obtained and patients are transitioned to partial weight bearing in the frame once signs of trabeculation appear. Partial weight bearing most commonly begins by the eighth week, with full weight bearing in the circular frame by the 12th week. Patients should be placed in either a protective cast or below-the-knee brace following frame removal until a custom locked nonarticulated ankle-foot orthoses (AFO) is constructed.

Complications and Outcomes

Complications should be expected and handled quickly and aggressively. Mendicino et al illustrated the increased risk of diabetics to develop major complications in IMN procedures (70). Stuart and Morrey experienced a complication rate of 78% if Charcot was present (71). This includes but are not limited to nonunions, delayed unions, malunions, infections, wound healing problems, hardware complications, pin track infections, tibial fractures, postoperative edema, and a number of serious medical complications, including the increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus.

CALCANECTOMIES

Heel ulcerations are a frequently encountered clinical entity, often the result of prolonged static bed rest. They are typically located along the posterior surface; however, plantar heel ulcers occur too. Nonhealing wounds should be evaluated for chronic infection or osteomyelitis. Most importantly, the vascular status must be carefully assessed in this setting.

Indications

Depending on the size of the problematic bone, a simple exostectomy may be adequate; however, for more extensive involvement, some type of calcanectomy may be required (Fig. 4.32). Calcanectomies are only recommended for well-perfused limbs when ulceration with osteomyelitis exists or if the patient is minimally ambulatory and primary wound closure is desired. The goals of a calcanectomy are to remove infected bone and create redundancy for primary wound closure, which should help facilitate wound healing to avoid more proximal amputations.

Figure 4.32 Example of a large posterior heel ulcer requiring subtotal calcanectomy.

TABLE 4.3 Calcanectomy Classification

Class

Definition

Total calcanectomy

Complete removal of the calcaneus

Subtotal calcanectomy

Partial resection of the calcaneus, including removal of the calcaneal tuber with detachment of the Achilles tendon

Partial calcanectomy

At least one third of the calcaneus resected but Achilles tendon still intact. This may include plantar fascia detachment

Calcaneal dé bridemen

Removal of less than one third of the calcaneus with an intact Achilles tendon

Adapted from Cook J. A retrospective assessment of partial calcanectomies and factors influencing postoperative course. J Foot Ankle Surg 2007;46(4):248–255.

CALCANECTOMY CLASSIFICATION. There are three degrees of calcanectomy; the most extreme is the total calcanectomy. Indications for a total calcanectomy are limited and often result in destabilization of the ankle joint. More commonly, the partial and subtotal calcanectomies are used to achieve the goals previously mentioned. The exact definition of each procedure has not been previously described and is generally related to the amount of bone resected. At our institution, we consider the procedure to be a partial calcanectomy if at least one third of the calcaneus is resected. However, if the resection requires removal of the calcaneal tuber and therefore Achilles tendon detachment, it is classified as subtotal calcanectomy (Table 4.3).

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree