- Adolescence is characterized by significant and complex biological, social and psychologic changes that occur during the teenage years.

- Adolescents with diabetes establish a long-term positive bond with their pediatric health care team. Consequently, the transition to an adult diabetes service provider is a significant event.

- Adolescents are at risk of dropping away from health care professional contact and follow-up during the time of transition, which may be detrimental to their physical and psychologic well-being.

- Adolescents need support to anticipate the issues they may face when preparing to move from children’s services and to identify the solutions that may be available to them.

- The transition must be carefully managed so that the adolescent does not need to make an abrupt adaptation in their move from an environment that is very supportive to one where they are expected to be more independent.

Introduction

Adolescence is a life stage characterized by transition and change regardless of health status. Diabetes in adolescence is a life-changing condition requiring diligent and consistent management by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians in addition to comprehensive care and support provided by the family unit. Many young people with diabetes establish a long-term positive bond with their pediatric health care team. Consequently, the transition to an adult diabetes service provider is a significant event. The seamless transfer of adolescents with diabetes from pediatric to adult services can also be a challenge for health services and clinicians. Young people may mourn the loss of the relationships they had with the pediatric health team and can become distressed about learning to trust new staff [1]. There is evidence to suggest that during the time of transfer, adolescents are at risk of dropping away from health care professional contact and follow-up which may be detrimental to their physical and psychologic well-being [2]. As a result, it has been estimated that 10–60% of adolescents do not make the transition successfully from pediatric to adult health services [3,4]. The purpose of this chapter is to enhance understanding of the key issues presenting for adolescents and clinicians, and to consider effective models of care that will facilitate seamless transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care.

Transition

Transition is the reorientation that people experience to a change event [5]. Events that change our lives occur constantly, but they often go unnoticed, unless we are disrupted by them. These are “change events” that produce an end to one’s familiar way of living and require the individual to find new ways of being in the world that incorporate those changes. Change is situational, such as a move to a new job, a new city or a new school. Transition is the way people respond to the changes that are occurring in their lives.

Transition involves moving through the change situation and negotiating one’s sense of self in an altered world [6]. Transition is the movement people make through a disruptive life event so that they can continue to live with a coherent and continuing sense of self [7]. Understanding transition involves exploring the person’s responses to a passage of change. Health care professionals are frequently in the position of supporting people who are in transition because of the changes associated with the impact of illness.

During the last three decades, the concept of transition has evolved in the social sciences and health disciplines, with nurses contributing to more recent understandings of the transition process as it relates to life and health [8–15]. Transitional definitions alter according to the disciplinary focus, but there is broad agreement that transition involves the way people respond to change. Transition occurs over time and entails change and adaptation, for example developmental, personal, relational, situational, societal or environmental change, but not all change engages transition. Transition is not an event, but rather the inner reorientation and self-redefinition that people go through in order to incorporate changes into their lives [5].

The transition focused on here when discussing adolescent transfer to adult services is when one “chapter” of life is over and the person is unable to go back to the way life was before the change event occurred. The change event under particular focus is the shift to a new and unfamiliar service environment. To enable a “new chapter” to begin these adolescents will need to respond to the changes in their lives, sorting out what can be retained of their former way of living and what has to be released, in order to move forward [15]. This is often the experience of the adolescent moving from child to adult health services. Understanding transition theory will enable health care professionals to assist young people to make this transition during a life stage that is characterized by constant change.

Transition as a process

The terms “transition” and “transfer ” have been used interchangeably in the literature when referring to adolescents moving between diabetes services. As a consequence, transition may be interpreted as simply a process of physical transfer to a different service with a failure to acknowledge the psychosocial needs of the adolescent and family members. This oversight may have resulted in a lack of resources to assist the adolescent and parents to make the psychosocial transition between children’s and adult services [1]. A clear distinction between the concepts of transition and transfer is needed.

When people experience transition, they look for ways to move through the unfamiliar to create some order in their lives so they can reorient themselves to the new situation [5]. Transition can involve much trial and error, as people work out ways of living and being in their changing world. When young people are learning to live with a chronic illness such as diabetes they are involved in that transitional process. Over time these people redefine their sense of self, redevelop confidence to make decisions about their lives and to respond to the ongoing disruption that so often accompanies chronic illness. When undertaking the work of reclaiming their sense of self and identity, they come to an understanding of what is changing, or has changed in their lives and how this reality is shifting key values and identity markers.

The transitional process takes time, however, as the adolescent will disengage with what was known and familiar and look toward the altered and new situation that lies ahead. At this point it can be helpful for the person to connect with others they can trust. A familiar health professional, support group, a friend or a family member who is a good listener becomes an important asset in the sense-making process. Without such examination of the change event or events, people’s understanding of what is changing may be limited. This is particularly the case for adolescents who are engaged in major change in all areas of their lives. For many adolescents, leaving the care of their pediatrician and other familiar health care professionals is a passage from security to uncertainty [16]. These young people need time to examine their perceptions and experiences and to consider the actions that they need or want to take. Adolescents will need support to anticipate the issues they may face when preparing to move from children’s services and to identify the solutions that may be available to them. This is a key point in enabling successful transition for adolescents moving to adult diabetes care.

Adolescence as a time of transition

Adolescence is a transitional stage of human development that occurs between childhood and adulthood. This transition is characterized by significant and complex biologic, social and psychologic changes that occur during the teenage years. During this time the adolescent is developing a sense of self and identity, establishing autonomy and understanding sexuality. Adolescence is a stage of life where control–autonomy–dependence are pertinent issues in the lives of young people [16]. There is often anxiety experienced by the adolescent regarding acceptance by peers which may also impact self-care behaviors.

The events and characteristics that mark the end of adolescence and the beginning of adulthood can vary by culture as well as by function. Countries and cultures differ at what age an individual can be considered to be mature enough to undertake particular tasks and responsibilities such as driving a vehicle, having sexual relations, serving in the armed forces, voting or marrying. Adolescence is usually accompanied by an increase in independence allowed by the parents or legal guardians and generally less supervision in daily life. This is true too of adolescents transferring to an adult care service. The intention is to ensure that the adolescent has the practical and cognitive skills required for diabetes self-care and has developed the capability to interact with others such as health care providers; however, age itself may not be a reliable indicator, as adolescents may have different needs and developmental issues at different stages and mature at different rates. The parents of the adolescent must also be prepared to relinquish some of the responsibility for diabetes care which they may have undertaken with a high degree of vigilance for many years. For some parents, this shift in responsibility can be a time of high anxiety. Fundamental to any successful transition program is the work with parents to help them find a balance between shifting the responsibility to the adolescent and continuing to maintain an appropriate level of interest and family cohesion [4].

Adolescence and diabetes

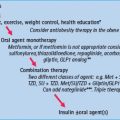

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is the most common metabolic disease that affects children [17]. It occurs when the pancreas is unable to produce insulin. Treatment consists of at least twice daily insulin injections in order to prevent serious short and long-term complications. In addition, children and their families need to ensure that an appropriate diet and lifestyle is followed and blood glucose levels are closely monitored [17].

For an adolescent with diabetes, the rapid changes in physical, sexual, psychologic, social and cognitive function that occur with adolescence can often lead to a decline in self-care behaviors. Glycemic control during adolescence can be suboptimal [18] because of a number of factors such as the physiologic changes associated with puberty [19], a desire to be perceived the same as peers, poor adherence to insulin regimens and decreased attendance at diabetes care clinics [2]. Irregular attendance at clinics has been associated with poor glycemic control and increased rates of diabetes-associated complications [20].

Adolescents who live with T1DM may experience the transition from the children’s to the adult health service as an additional burden over and above the everyday challenges of becoming a young adult because achieving glycemic control may have a significant impact on daily life [ 21–24]. Clinicians working in both children’s and adult services have raised concerns that young people transferring between services often fall through service gaps. Scott et al. [4] found that 90% of adolescent survey respondents had felt “lost in the shuffle” when making the transition from pediatric to adult diabetes services.

Adolescence is a time when many young people have not received adequate follow-up until a crisis has forced them back into the system [1,3,21]. Transition in this context was defined by Blum et al. [25] as “Ahe purposeful, planned movement of adolescents with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centred to adult-orientated health care systems.” This definition has been widely applied within a wide spectrum of clinical practice, guidelines and research studies and focuses on the passage between two points within the health care system. The authors contend, however, that a broadening of this definition is needed because the adolescent’s transitional process of inner reorientation also has to be considered in order to provide holistic care.

A systematic review conducted by Fleming et al. [21] highlighted the need for collaboration between children and adult services, particularly in light of the well-documented differences between these services [22, 26–28]. Some of the differences between services have been identified as decreased parental involvement in adult services and significant differences in clinical practice and culture [29]. While it has been acknowledged that it is necessary for the children’s and adult services to have different foci, it is argued that collaboration is needed to help bridge the gap so that transition is experienced by the adolescent as a smoother process [21,22].

Transition in the diabetes care setting

The process of transition in the diabetes care setting involves both the physical transfer of an adolescent from one health care setting to the other (pediatric to adult) as well as the acquisition and practice of self-management skills and the shift of responsibility of care from parent to adolescent. Transition therefore is not only the physical transfer of an individual moving between health services, but also the environmental, emotional and psychologic factors that are encompassed in this process. Transition is a progressive process that involves patient, health care provider and family or carer and effectively commences, in one dimension or another, once a child is diagnosed with diabetes.

Components of transition

It is useful for the purpose of understanding the complexities of transition to investigate the tasks that are accomplished when transition is successfully achieved. Successful transition involves the accomplishment of a number of tasks, as follows.

Adolescent needs during transition

Rarely have young people been asked what their needs are during transition. This is surprising given that the transition between diabetes services often occurs concurrently to the time of significant change in the adolescent’s life.

A qualitative study undertaken by Visentin et al. [33] found that adolescents focused on the medical transfer of care during transition. The focus on medical care may be because many adolescents had not regularly seen any other health care professional. Adolescents stated they were interested in being introduced to the diabetes nurse educator and dietitian at the adult services [33]. Kipps et al. [3] reported a higher rate at attendance of adult services when the adolescent had met a member of the adult team before transfer which signifies the importance of prior contact and collaboration.

The precise needs of adolescents will vary according to culture and circumstances [34] and so research at the service level will be required to ensure services are tailored to need. Flexibility seems to be the key, because young people may be ready to transfer to adult services at different times, dependent on their cognitive and physical development, emotional maturity and general health [34]. The role of health professionals in this process is to tailor advice to young people based on their developmental and cognitive level [29].

During this transitional process, adolescents with diabetes need a shared understanding of their needs from their health care provider. This requires consultation with adolescents themselves [33], planning, ongoing contact and feedback between care providers in the two health care systems, and evaluation of services [35].

Promoting self-care

Promoting better management for adolescents with T1DM by developing their capacity to self-care through healthy choices prior to transition to adult services is an optimal goal. Gradual and early promotion of self-care is particularly important during adolescence when young people may try to act out behaviors in order to demonstrate independence. A cross-sectional multisite study of adolescents was conducted with 130 young people, studying factors that affect blood glucose control, such as how they care for themselves, eating problems, relationships, depression and health issues [36]. The research found that poor self-care, disturbed eating behavior, depression and peer relations were all associated with poor blood glucose control. Where there were good family relationships and support from parents, girls achieved better control than boys. The researchers suggest that further research should look at the reasons behind these relationships. The authors propose that monitoring of diabetes knowledge and promotion of self-efficacy from late childhood may optimize the transfer of self-care knowledge and behaviors from parents to adolescents [36].

Adolescence and young adulthood is characterized by a number of cognitive, emotional, behavioral and social changes that can present as barriers to effective self-management, including engagement with health care services. Cognitive changes include a shift in thinking from concrete to abstract and the ability to engage in introspection. These new cognitive skills give the ability to reflect on self-identity (self-concept and self-esteem). Adolescence is also a time of experimenting with new behaviors and, in particular, risk-taking behaviors. Socially, the importance of peers significantly increases at this time and concerns with being accepted by peer group are strong.

Successful transition can only be facilitated by provision of appropriate services, programs and resources. Long-term success is heavily dependent on instilling adequate self-care behaviors and self-advocacy skills so that adolescents can deal appropriately with external factors such as home, school and work life which may present as obstacles to effective diabetes management.

Education programs to promote self-care

A powerful predictor of good self-care is self-efficacy. For the purposes of this chapter, self-efficacy can been seen when adolescents have confidence in their capability to make decisions and take actions that demonstrate diabetes self-care. Education programs that enhance self-efficacy by incorporating personal health care goals and social and peer support have been shown to improve health outcomes and facilitate smooth transition in adolescents and young adults with T1DM [30]. Cook et al. [37] describe a pilot study demonstrating how the problem-solving behavior of adolescents with T1DM was improved through participation in a workshop style education program. The Choices Program consisted of six small weekly group workshop style sessions where adolescents came together to discuss major diabetes management problems, including psychosocial issues, and work together to identify solutions. This program demonstrated an increase in the practice of diabetes health care behaviors such as blood glucose monitoring and exercise. Cook et al. [37] identified three principles that are key to the success of an education program: parental involvement, integration with clinic (e.g. to allow implementation of regimen changes) and six or more sessions plus multiple follow-up and review sessions.

Education programs should be based on current learning and behavior change theories and should be developed with these key principles in mind. Furthermore, education programs should be part of standard care as well as specific elements in formal transition care programs.

Barriers and facilitators to successful transition

Many authors emphasize the need for collaboration between pediatric and adult diabetes services so as to create a smooth transition for adolescents [1,21,23,28,32]. These authors recommended that transition should be planned and coordinated [21,23,28,32]; however, the reality is that unless there is a transition program in place, adolescents transfer to adult services in an ad hoc manner with little planning, consultation or case management [33]. Hence, the absence of guidelines for the development, implementation and evaluation of transition programs must be viewed as a significant barrier to successful transition. Authors from Australia, the UK and the USA have called for the development of national policies that inform transition for adolescents with chronic conditions [1,21,23,28,32]. More recently, countries such as the UK, Australia and Canada either developed or made progress around developing standards and guidelines for policies in order to improve transition outcomes and experiences. For example, Diabetes Australia – Victoria is undertaking a project to develop a state-wide coordinated transition system for individuals living with T1DM. In addition, some professional organizations have developed best practice guidelines to inform the care of adolescents transferring to adult services. The successful translation of these guidelines into practice, however, remains unclear.

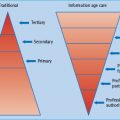

It has been acknowledged that transition to adult services can be difficult for a myriad of reasons. The most reported concern is the notable differences in the approach to care between children’s and adult diabetes services. Children’s services focus on the whole family and assume the child has little or no knowledge about diabetes and management. The adult sector take a more individual approach and assumes the patient has decision-making capacity and is knowledgable about diabetes and has the necessary skills to navigate the complex health system [26,28]. In addition, adult services expect a much greater degree of independence from young people and encourage communication without parents being present. It may be difficult for adolescents to adapt to this type of relationship, particularly when they have had a long-standing relationship with their pediatrician [22]. The adolescent may experience significant difficulty if the pediatric health care provider has not recognized the need to up-skill the adolescent in self-care behaviors before transfer to an adult service. A helpful approach to assist adolescents to transition is to focus on the location of the actual aspects that are changing, then to explore how the changes are being experienced by the individual, followed by consideration of how the person is responding or may respond [15].

Adult service staff may make the assumption that the adolescent has the necessary skills and maturity to be able to plan their future and have the insight to understand the consequences if they choose not to undertake diabetes self-care [21,22]. Viner [1] argued that adolescents are not served well by either model of diabetes care because the children’s clinic may not acknowledge their growing independence while the adult clinic may not acknowledge their growth, development and family concerns. It has been recommended that transition be “a family affair” [27] and that transition in health care is acknowledged as only one aspect of a broader life transition that adolescents move through [1].

If the transition process is not meeting the needs of adolescents then they may choose to drop out of the system. While adolescents may continue to access a primary care physician for the prescription of insulin, it is thought that a multidisciplinary approach to diabetes care provides optimal management [38,39]. If diabetes is poorly managed, young adults are at an increased risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications as well as life-threatening acute complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) [40].

The demands of diabetes may be experienced as difficult during the adolescent years and it has been documented that glycemic control at this life stage often deteriorates [21,22,41,42]. The deterioration in glycemic control is thought to be related to an increase in insulin resistance that relates to physiologic changes in puberty coupled with the psychosocial pressures associated with this period [41,42]. Of further concern, glycemic control in young people in the 16–25 year age group was found to be poorer than at other times during the lifespan [43].

The health professionals participating in the study of Visentin et al. [33] expressed concern about exposing adolescents to older people with type 2 diabetes, particularly if those older patients had obvious complications of diabetes such as amputations. Interestingly, adolescents claimed that such exposure was not an issue for them.

The experiences of adolescents with diabetes living in rural or remote areas have been rarely reported. There appears to be an assumption that adolescents have easy access to services; however, this may not be the case in many counties. In a study by Cameron et al. [44], adolescents in rural areas were found to have poorer outcomes than young adults from metropolitan areas, particularly in the areas of mental health, self-esteem and family cohesion. The authors considered a major factor in the differences in these outcomes was a lack of transition programs and other support services. Another factor was that adolescents with diabetes living in rural and remote areas may have less access to peers who also have diabetes, leading to a lack of peer support.

Models of transition care

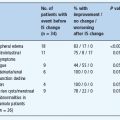

While the literature has outlined principles for successful transition and made suggestions for model development, there is limited research that provides outcome data to support one model over another [1,3,30]. A study undertaken in the UK compared different models of transfer within one region using data generated through interviews and retrospective casenote review [3]. The models evaluated were:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree