Diabetes—A Worldwide Problem

Paul Zimmet

Jonathan Shaw

In recent years, the global community has been preoccupied with the threat of a resurgence of infectious diseases, old ones such as tuberculosis and newer ones such as human immunodeficiency virus-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV-AIDS) and the Ebola virus. However, diabetes is a growing public health problem throughout the world. Currently, approximately 171 to 194 million people in the world have diabetes, the majority of the cases being type 2 (1,2). This number is expected to increase to more than 330 million by the year 2025—a doubling within a single generation. This spectacular increase in the frequency of type 2 diabetes is being paralleled by a similarly alarming increase in obesity (3), which is one of the major risk factors for type 2 diabetes (4). Because of the close linkage between these two conditions, Ziv and Shafrir have suggested the term “diabesity” to describe this association (5).

This dual epidemic, which was largely ignored by the public health community until recently, has come as a great surprise. In addition, the public health community, both national and international, has been very slow to recognize the huge socioeconomic and public health threat from diabetes and its devastating complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and, most importantly, cardiovascular disease (CVD) (6,7). However, diabetes and its huge personal and socioeconomic costs are increasingly being recognized as a major global health and societal problem, particularly by the World Health Organization (8) and the World Bank (9). Diabetes is now among the five leading causes of death due to disease in most countries (10). The costs are enormous economically, as well as in terms of health. By the most recent estimates, for example, diabetes costs the United States approximately $132 billion annually (11).

WORLDWIDE PREVALENCE OF DIABETES

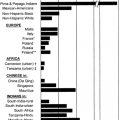

Epidemiologic studies have provided overwhelming evidence that the prevalence of diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, is increasing rapidly in many nations (12). Between 1976 and 1988, the prevalence of diabetes (among people age 40 to 74 years) rose from 11.4% to 14.3% in the United States (13). In China (14), a prevalence of 3.1% in 1994 (in those older than 25 years), although relatively low by international standards, was almost two and a half times higher than a figure from the Chinese province of Da Qing 8 years earlier. Two cross-sectional studies in an urban south Indian population showed that the prevalence in persons older than age 20 years had increased from 8.3% in 1989 to 11.6% in 1995 (15). In Denmark, a 38% increase in diabetes prevalence has been reported over 22 years (16). Our data on the national prevalence in Australia reveal a prevalence of diabetes of 7.4% (16), whereas 20 years ago, the best estimate was 3.4% (17). Overall, the highest rates are seen in Native Americans and Pacific Islanders, followed by Hispanics or Mexican Americans, people originating from the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asians, and African Americans. The prevalence in Europeans is somewhat lower, and diabetes remains rare only among indigenous peoples living a traditional lifestyle.

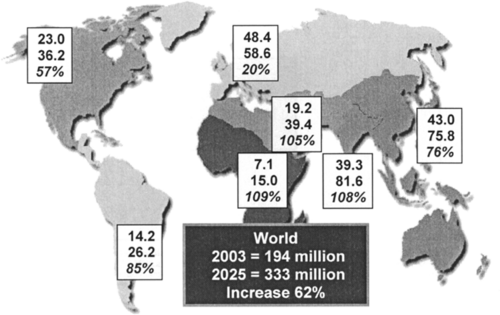

We recently published global diabetes estimates for 2003 and projections for the year 2025 (2) in order to raise the profile of diabetes in a global perspective. Furthermore, we hoped to encourage governments to initiate or improve local diabetes monitoring and prevention strategies. We estimated that 194 million people were likely to have diabetes globally in 2003 i.e., about 5.1% of the world population. By the year 2025, the total number of people with diabetes is projected to reach 330 million worldwide (Fig. 30.1). The region most likely to experience the main brunt of the epidemic is Asia. Here, diabetes could become two to three times more common than it is at present. Over the next 25 years, India alone is expected to see an increase from 36 to 73 million people with diabetes, and China will see a rise from 24 to 46 million.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION

Paradoxically, for many countries, type 2 diabetes has evolved as a major health problem in part because of increasing longevity (4). During the past century, improved nutrition, better hygiene, and the control of many communicable diseases have dramatically improved longevity, but these benefits have unmasked many age-related noncommunicable diseases,

including type 2 diabetes and CVD (7,18). These formerly uncommon noncommunicable diseases have replaced many communicable diseases and are now major contributors to ill health and death.

including type 2 diabetes and CVD (7,18). These formerly uncommon noncommunicable diseases have replaced many communicable diseases and are now major contributors to ill health and death.

This phenomenon of shifting disease patterns, termed epidemiologic transition by Orman (19), has occurred in developed countries over the past 50 years but is now affecting many developing countries. The transition has catapulted type 2 diabetes from its position as a rare disease at the beginning of the 20th century to its current position as a major global contributor to disability and death and one of the major health challenges of the 21st century (7).

Although changes in lifestyle and disease patterns are seen around the world, it is in the developing nations, where traditional lifestyles have been lost, that these events are played out most dramatically. The use of the term traditional lifestyle has at least two dimensions that should be clearly delineated (20). Traditional in the context of the history of indigenous people can mean the time before contact with the European settlers (precontact), i.e., historical dimension. Alternatively, it can denote a lifestyle according to behavioral traditions, which have an impact on patterns of physical activity, composition of the diet, amount of food, and other factors of daily living, that is, the behavioral dimension. It is within this context that we use it here, particularly in relation to the diabetes epidemic in the Pacific and in the indigenous population of Australia.

In his book The Call Girls (21), the late Arthur Koestler suggested the term “Coca-colonization” as a means to describe the impact of Western societies on traditional sociocultural habits and way of life in developing countries. The devastating results of Western intrusion into the lives of traditional-living indigenous communities can be seen from the Eskimos in the Arctic Circle to the Maori (Polynesians) in New Zealand and into the remote and idyllic islands and atolls of the Pacific Ocean (7). During the 19th century, European explorers and voyagers brought many communicable diseases, such as measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis, influenza and venereal diseases, to the Pacific Island communities. In that century, nearly all of the islands suffered a drastic decline in population as a result of these imported diseases. In the mid-18th century, there were about 250,000 Maori in New Zealand. The intrusion of European ways, weapons, and diseases soon decimated their numbers to 90,000, so that by the early 20th century the Maori in that country seemed to be a dying race (7,22). The same scenario was repeated in Australia, with devastating effect on the Aboriginal population (6).

From a historical and teleological perspective, the main causes of morbidity and mortality in all countries of the world were epidemics of communicable diseases, including typhoid, cholera, smallpox, diphtheria, and influenza, until the latter part of the 19th century (18). While some of these diseases remain epidemic in many Third World countries, industrialization and progressive modernization of societies have seen major improvements in housing, sanitation, water supply, and nutrition. Accompanied by the development of antibiotics and immunization programs, this scenario has radically changed the profile of diseases—initially in developed countries and later in many developing countries.

THE EPIDEMIC IN PROGRESS—WHAT ARE THE MAJOR FACTORS?

At the same time that the threat of communicable diseases has decreased, rapid socioeconomic development and “Coca-colonization” have resulted in a change in the way of life from traditional to modern (21). In virtually all populations, higher-fat diets and decreased physical activity have accompanied the benefits of modernization. Exercise has been engineered out of our daily lives, both in the workplace and at leisure (23). These

lifestyle changes have been well documented in Canadian (24) and Native-American communities, Pacific and Indian Ocean island populations (25), and Australian Aboriginal communities (26). When combined with increasing longevity, these changes form the basis of the dynamic type 2 diabetes epidemic we are witnessing today.

lifestyle changes have been well documented in Canadian (24) and Native-American communities, Pacific and Indian Ocean island populations (25), and Australian Aboriginal communities (26). When combined with increasing longevity, these changes form the basis of the dynamic type 2 diabetes epidemic we are witnessing today.

The explosion of type 2 diabetes in Native-American and Pacific Island populations (with rates of up to 40% in communities where diabetes was virtually unknown 50 years previously) points the finger squarely at environmental causes, albeit in populations with a high genetic susceptibility to type 2 diabetes (4). The increase has occurred far too quickly to be the result of altered gene frequencies. However, the magnitude of the differences between ethnic groups when exposed to similar environments also implicates a significant genetic contribution. Jared Diamond, the noted American biologist and author, has suggested that the lifestyle-related diabetes epidemic in Native Americans and Pacific Islanders probably results from the collision of our old hunter-gatherer genes with the new 20th century way of life (27). The Western lifestyle must have unmasked the effects of preexisting genes, because the consistent result has been diabetes within a few decades.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree