DESCRIBING PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF AGING

PEARLS

❖ Full life development theories, such as those by Erikson, Jung, and Maslow, discuss accomplishment stages throughout life for successful aging.

❖ Late life development theories, such as those described by Peck, Buehler, Neugarten, and Havighurst, focus on the state of late life and the older person’s role in adapting to this stage of life.

❖ Intellectual performance in older adults can be enhanced by the therapist in many ways, including the mode of information presented, pacing, and feedback.

❖ Institutionalization causes changes in behavior and affects a person’s performance. These effects can be countered with recognition of symptoms and behavioral and environmental interventions.

❖ Anxiety disorders, such as adjustment disorders, anxiety states, and phobic states, are often underreported and missed in older adults.

❖ Dementia affects millions of older persons and can be classified as acute disorders, chronic disorders, and presenile dementias. Assessment and treatment modification for working with these patients is based on behavioral and environmental modification by the therapist.

❖ Recognizing one’s belief systems via the Facts on Aging Quiz can help the therapist work well with older adults.

The aging process of all aspects of human life is not one dimensional. Besides the obvious physical component, there exist the psychological, emotional, and spiritual components of aging. This chapter addresses the psychosocial components. Even though physical health is extremely important, studies and life experience illustrate the effects of cognitive perception on life satisfaction and physical health.1,2 One study on hip fracture outcomes for older persons showed that the most important variable in successful rehabilitation was the presence or absence of depression.3 This study alone has tremendous implications for physical and occupational therapists because it illustrates that unless the older person’s emotional and mental abilities are addressed, the physical efforts may have minimal effect.

How does a physical or occupational therapist work in the psychosocial realm? Rehabilitation therapists are not psychologists and do not receive extensive training in the social and psychological sciences. Nevertheless, they can use specific information as an adjunct to daily treatment. For example, examining one’s attitudes based on the various psychosocial theories of aging may provide information about a patient’s satisfaction or motivation and enhance a therapist’s ability to communicate with an older person. In addition, because the goal of physical therapy is to achieve optimal functioning, it is imperative that the therapist be able to recognize situations that require coping mechanisms and provide some assistance in these situations.

This chapter explores the theories of aging and the cognitive changes in late life. Situations, both normal and pathological, that require coping mechanisms as one ages are discussed.

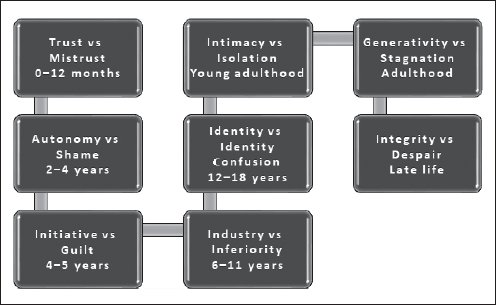

Figure 4-1. Graphic presentations of proposed choices in ego development and the associated age range. (Adapted from Erikson EH. Identity, Youth & Crisis. New York, NY: Norton; 1968.)

PSYCHOSOCIAL THEORIES OF AGING

In the past 30 years, many psychological theories of aging have been proposed. Prior to this time, however, very few theories existed. The mainstream of thought centered around the theories of Freud and Piaget, which placed all the emphasis on the psychological development of the child while essentially ignoring the adult. The theories discussed in this section are either full life development theories or late life psychological development theories.

Full Life Development Theories

Erikson

Eric Erikson was one of the first psychological theorists to develop a personality theory that extended into old age. Erikson viewed the process of human development as a series of stages that one goes through in order to fully develop one’s ego.4 Erikson describes 8 stages in this process. These stages are listed in Figure 4-1. Each of these stages represents a choice in the development of the expanding ego. The last 2 stages are of particular interest to the practitioner working with the older person.

A successful life choice of generativity consists of guiding, parenting, and monitoring the next generation. If an adult person does not experience generativity, then stagnation will predominate. Stagnation is evidenced by anger, hurt, and self-absorption. The final stage of Erikson’s theory suggests that the older person must accept his or her life with the sense that “If I had to do it all over again, I’d do it pretty much the same.”5 At this stage, the person experiences an active concern with life, even in the face of death, and learns to experience his or her own wisdom.

Jung

Carl Jung’s theory on development was one of the first to designate adult stages on the basis of his own experience in clinical theory and practice.6 His theory described the youth period, from puberty to middle age, as a stage in which the person is concerned with sexual instincts, broadening horizons, and conquering feelings of inferiority. The adult stage, between the ages of 35 to 40, involves the transport of the youthful self into the middle years. During this stage, Jung theorized that the person’s convictions strengthen until they become somewhat more rigid at the age of 50. In later years, Jung suggests that activity levels decrease, that men become more expressive and nurturing, and that women become more “instrumental,” providing care and continuation of the generations they have nurtured in their lives.6,7 Jung also suggests that the later years are years in which the older person confronts his or her own death. Success in this involves the acceptance of imminent death as a part of the cycle of life, not something to be feared.

Maslow

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs is not a theory singular to aging, but it is an excellent framework for exploring growth, development, and motivation.8 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a pyramid of needs, each of which builds on the other. In the lowest level, biological and physiological integrity, the person needs to feed him- or herself and keep him- or herself warm and clothed. At the second level, safety and security, the person needs protection against the elements and against other people. This cannot be achieved unless the person is first fed and clothed. At the third level, belonging or love needs, the person begins to seek love from other persons, such as a parent or a significant other. When the person satisfies the need for love, he or she can then progress to the next level, self-esteem, where the person cherishes him- or herself, respects his or her own values and ideas, and feels good about who he or she is. Finally, at the level of self-actualization, the person no longer worries about the lower needs but is now able to give to others and has reached a higher level transcending the lower self-esteem needs. At the pinnacle of the pyramid of need, individuals can nurture and feed others, develop their own ideas, and actually live their own values and ideas in the community. According to Maslow, very few people in society are self-actualized. Some of our great leaders such as Martin Luther King, Winston Churchill, and Golda Meir were self-actualized people.

A person must successfully fill the lower need before ascending to the higher need. When a person is at a certain level, his or her energies are consumed at that level.9 A person rarely stays at a higher level, but rather the person reverts to lower levels when the lower needs are not met. For example, a recently widowed woman may feel isolated or lonely and be unable to experience the higher levels of self-esteem or self-actualization until her grief has subsided.

This theory is particularly useful in the area of motivation. Because older persons are more likely to have physical decline, their needs will descend to the lower levels of the hierarchy. Therefore, motivation strategies should be aimed at the level of the person’s needs. For example, if the person is unstable when walking, then strategies to encourage exercises in this area should appeal to his or her sense of safety if the person is at that level. However, if the same person is more concerned about hunger during a treatment session, he or she will be unable to focus on the exercises. Maslow believes that it is truly the older person who has the knowledge and experience of life to be able to experience self-actualization, the highest level of the paradigm.9

Late Life Development Theories

Peck

Robert C. Peck’s theory describes tasks that must be accomplished to achieve integrity in old age. In this theory, the burden is placed on the older person to redefine the self, dismiss occupational identity, and go beyond selfcenteredness. In order to accomplish this, Peck proposed the following tasks10:

❖Ego differentiation vs work role preoccupation: In this instance, a retired person must look for new meaning and values beyond his or her previous work roles.

❖Body transcendence vs body preoccupation: Because old age may carry with it ill health, the older person must learn new ways to gain mental, physical, social, and spiritual pleasure that transcend physical discomfort.

❖Ego transcendence vs ego preoccupation: This last stage is a way of minimizing the prospect of death by giving to children and making charitable contributions to leave an enduring legacy.

Buehler

Cheryl Buehler adopts a biophysical model of a living open system in which both maintenance and change of the organism are equally important.7 She purports 2 kinds of maintenance: satisfying need and maintaining internal order. Two types of change are also proposed: adaptation and creativity. According to Buehler’s theory, maturity is the age of fulfillment, and in order to successfully go through each stage of aging, these 4 basic elements must be met to ensure acceptance of old age. Successful passage through each of these stages requires integrating and balancing conflicting and competing trends from earlier stages. In middle age, self-assessment evolves, and whatever order existed previously is questioned. Self-assessment is achieved when an individual accepts him- or herself and others for who they are, has a fresh appreciation of people and the world, and is autonomous and serene within oneself, resulting in self-actualization. This introspection and reevaluation of maintenance and change determine how one faces old age—optimistically or pessimistically.

Neugarten

Bernice Neugarten also describes the tasks that must be accomplished in order to be a successfully aging older person. The following are a few of her tasks that directly impact the rehabilitation milieu11:

❖ Accepting the increasing reality and imminence of death

❖ Coping with physical illness

❖ Coordinating the necessary dependence on support and accurately assessing the independent choices that can still be made to achieve maximum life satisfaction

❖ Giving and obtaining emotional gratification

Disengagement Theory

The controversial disengagement theory credited to Cummings and Henry in the 1950s postulated that older people and society mutually withdraw. This withdrawal is characterized by a positive change in psychological well-being for the older person.12 This theory, although not widely accepted at present, has spawned much debate on the subject of late life adaptation. This theory is based on the sociologic perspective of functionalism whereby the assumption is that society has certain needs that must be fulfilled if stability and equilibrium are to be maintained. A structure is said to have a function if it contributes to the fulfillment of one or more of the social needs of the system.13

The disengagement theory depicts aging as a process of gradual physical, psychological, and social withdrawal. Disengagement is considered as functional during the aging process, purportedly preparing the person and society to face the inevitability of death. Changes in the personality of the individual are viewed as either the cause or the effect of decreased involvement with others. The authors of this theory claim that once this process starts it is irreversible and that morale may remain high or improve as part of the process of disengagement.

Within this process, Cummings and Henry have described 3 types of changes resulting in an older person becoming less tied to the social system.12 There are changes in the amount of interaction, the purposes of interaction, and the style of interaction with others. In outlining their theory, Cummings and Henry indicate that the process is both intrinsic and inevitable and that the process is not only a correlate of successful aging but may also be a condition of it because those who accept this inevitable reduction in social and personal interactions in old age are usually satisfied with their lives.12

Cummings and Henry provide 9 postulates that summarize the theory of disengagement. These postulates14 are as follows:

❖Postulate 1: Everyone expects death, and one’s abilities will likely deteriorate over time. As a result, every person will lose ties to others in his or her society.

❖Postulate 2: Because individual interactions between people strengthen norms, an individual who has fewer varieties of interactions has greater freedom from the norms imposed by interaction. Consequently, this form of disengagement becomes a circular or self-perpetuating process.

❖Postulate 3: Because men have a centrally instrumental role in America and women a socioemotional one, disengagement differs between men and women.

❖Postulate 4: The individual’s life is punctuated by ego changes. For example, aging, a form of ego change, causes knowledge and skill to deteriorate. However, success in an industrialized society demands certain knowledge and skill. To satisfy these demands, age grading ensures that the young possess sufficient knowledge and skill to assume authority and the old retire before they lose their skills. This kind of disengagement is affected by the individual, prompted by either ego changes or the organization—which is bound to organizational imperatives—or both.

❖Postulate 5: When both the individual and society are ready for disengagement, complete disengagement results. When neither are ready, continuing engagement results. When the individual is ready and society is not, a disjunction between the expectations of the individual and the members of this social system results, but engagement usually continues. When society is ready and the individual is not, the result of the disjunction is usually disengagement.

❖Postulate 6: Man’s central role is work, and woman’s is marriage and family. If individuals abandon their central roles, they drastically lose social life space and so suffer crisis and demoralization unless they assume the different roles required by the disengaged state.

❖Postulate 7: This postulate contains 2 main concepts.

- Readiness for disengagement occurs if the following are present:

- An individual is aware of the shortness of life and scarcity of time.

- Individuals perceive their life space decreasing.

- A person loses ego energy.

- An individual is aware of the shortness of life and scarcity of time.

- Each level of society grants individuals permission to disengage because of the following:

- Requirements of the rational-legal occupational system in an affluent society.

- The nature of the nuclear family.

- The differential death rate.

- Requirements of the rational-legal occupational system in an affluent society.

❖Postulate 8: Fewer interactions and disengagement from central roles lead to the relationships in the remaining roles changing. In turn, relational rewards become more diverse, and vertical solidarities are transformed to horizontal ones.

❖Postulate 9: The disengagement theory is independent of culture, but the form it takes is bound by culture.

Today, however, this theory has been largely discredited.14 While agreeing that a person’s death may be dysfunctional for the social system if it is not prepared for, a reduction in activities in older adults associated with disengagement as one ages tends to result in a reduction in overall life satisfaction. Cummings and Henry claim that it is natural and acceptable for older adults to withdraw from society. The strong criticism of this theory postulates that the aging process is not innate, universal, or unidirectional as Cummings and Henry suggest.14 This is substantiated by recent studies of centenarians in which successful aging includes, as the second most important factor, attitude, outlook, and social relationships.15

Functionalism Versus Conflict Theory

The challenge to functionalism and the disengagement theory came from several sources. It was believed that functionalism is too consensus oriented, has a built-in conservative bias, and treats both change and conflict in society negatively. Although functionalists emphasize order, stability, and equilibrium and therefore can devise an orientation that assumes that the person and society mutually acquiesce to the withdrawal of the older adult, the conflict perspective is radically different. From the conflict perspective, consent and acquiescence take place through oppression, coercion, domination, and exploitation of one group by another. The conflict perspective stresses that there are always competing interests as groups struggle over claims to scarce resources, including status, power, and social class. While functionalists also assume that stratification is based on scarcity, the problem is often defined by functionalists as how to integrate the different sectors, groups, or classes. However, conflict theorists see the solution to this scarcity as occurring through the reduction of structural inequalities. They argue that these structural changes will occur only in the presence of intense struggle.16 This perspective is also shared by other research that attempted to explain certain ways of thinking about older adults as a social problem, which conflict theorists hypothesized are related to the structure of social and power relations.17,18

The key difference between functionalism and conflict theory is that, in functionalism, the society is understood as a system consisting of different subsections that have specific functions. On the other hand, the conflict theory comprehends society through the social conflicts that arise due to inequality that prevail among different social classes. The following outlines the differences in the characteristics of functionalism and conflict theory:

❖ View of the society

- Functionalism: The society is viewed as a system that consists of different parts.

- Conflict theory: The society is viewed as a struggle between different classes due to inequality.

❖ Approach

- Functionalism: Uses a macro approach.

- Conflict theory: Also uses a macro approach.

❖ Emphasis

- Functionalism: Stresses cooperation.

- Conflict theory: Stresses competition.

Exchange Theory

Another theoretical orientation that emerged as a reaction to functionalism is the exchange theory. Based on the belief that functionalism is too abstract and structural and cannot explain actual human behavior, the exchange theory is firmly rooted in rationalism (ie, human beings tend to choose courses of action on the basis of anticipated outcomes from among a known range of alternatives). Underlying this rational view of human behavior is the principle of hedonism, which is expressed in the contention that people tend to choose alternatives that will provide the most beneficial outcome. Everyone attempts to optimize gratification (ie, people continually try to satisfy needs and wants and to attain certain goals), and most of this occurs through interaction with other persons or groups. Persons attempt to maximize rewards while reducing costs. Voluntary social behavior is motivated by the expectation of the return or reward this behavior will bring from others. One gives things in the hope of getting something in exchange.19

Another proposition essential to the exchange theory is the principle of reciprocity. In its simplest form, it can be stated that a person should help (and not hurt) those who have helped him or her. The principle of reciprocity further assumes that a person chooses alternative modes of behaving by comparing the anticipated rewards, the possible costs that may be incurred, and the magnitude of investment required to achieve those rewarding outcomes. Accordingly, rewards in human social interaction should be proportional to investment, and costs should not exceed rewards or else the person will avoid that activity. Recent research and comparison of theories of aging20 have extended the principle of reciprocity to include another concept called distributive justice. When rewards are not proportional to investments over the long term, the assertion is that persons tend to feel angry with social relations, instability is created, and the propensities for conflict increase.

People exchange not only tangible and material objects but also intangibles, such as the expression of love, admiration, respect, power, and influence. A good example of how this exchange theory might be applied to the aging individual is that in the social exchange between older adults and society, older adults lose the availability of resources. By losing power, older adults are increasingly unable to enter into equal exchange relationships with significant others, and all that remains for them is the capacity to comply.21 Just as the conflict theorists focus on inequities and class struggle, the exchange theorists believe that to understand the situation of older adults, we must examine the relationship of society’s stratification system in the aging process.21

Continuity and Activity Theories

Two well-known theories that developed in response to the disengagement theory are the continuity and activity theories. The continuity theory proposes that activities in old age reflect a continuation of earlier life patterns,22 whereas the activity theory states that successful adaptation in late life is associated with maintaining as high a level of activity as possible. The older person should find substitutes when a meaningful activity, such as work, must be terminated. The person should develop an active rather than passive role toward his or her daily life as well as toward biological and social changes that are taking place.23

The continuity theory assumes that in the process of becoming adults, persons develop habits and preferences that become part of their personalities throughout their life experience. These habits and preferences are carried into old age. The continuity theory claims that neither activity nor inactivity assumes happiness. It posits that older people want to remain engaged with their social environment and that the magnitude of this engagement varies with the person according to lifelong established patterns and self-concepts.22 It further recognizes the interrelationships of biologic and environmental factors with psychological preferences. Positive aging becomes an adaptive process involving interaction among all elements.

The activity theory, which is related to social role concepts, was advanced as an alternative interpretation to disengagement. It affirms that the continued maintenance of a high degree of involvement in social life is an important basis for deriving and sustaining satisfaction. It claims that those who maintain extensive social contacts and engage in regular activities, similar to their engagement level in midlife, age most successfully. Thus, declines in activity and role loss are associated with lower levels of satisfaction.23

In sum, continuity and activity theories assume the need for continued involvement throughout life; disengagement assumes mutuality in the decline of involvement. The exchange theory assumes neither. It posits that the degree of engagement is the outcome of a specific change in the relationship between the person and society in which the more powerful exchange partner dictates the terms of the relationship.

Havighurst

Robert J. Havighurst’s theory on aging relates successful aging to social competence and flexibility in adapting to new roles. He believes in the importance of finding new and meaningful roles in old age while maintaining comfort with the customs of the time.24,25 Later, Neugarten and Havighurst noted that successful adaptation to age was related to personality and not age per se. They noted the following 4 personality types26:

- Integrated: Shows a high degree of competence in daily activities and a complex inner life (this type is generally the best adapter)

- Passive dependent: Seeks others to satisfy his or her emotional needs

- Armored: Attempts to control his or her environment and impulses and tends to be a high achiever

- Unintegrated: Shows poor emotional control and intellectual competency (this type tends to have the poorest adaptation in late life)

Levinson

Although Erikson focuses on ego and personality development, Daniel Levinson27 is concerned with the social tasks and roles that must be managed at each developmental stage of a person’s life. This theory is an extension of the Havighurst and Neuhaus theories regarding activity and aging. Levinson27 approaches the stages or “seasons” of adulthood as a developmental process involving occupation, love relationships, marriage and family, relation to self, use of solitude, and roles in various social contexts (eg, relationships with individuals, groups, and institutions that have significance for his or her life). According to Levinson, these components make up the underlying structure or pattern of a person’s life. He refers to this pattern as the person’s life structure. Two basic types of developmental periods are hypothesized as determining life structure: structure building and structure change.

Levinson identifies a “novice” phase of adult development that consists of 3 seasons: early adult transition (a structure-changing phase), entering the adult world (structure building), and transition (during which structure changing again takes place). The most important developmental tasks of early adulthood according to Levinson’s theory are entering an occupation, developing mentor relationships, and forming a love or marriage relationship. During the transition phase, the primary task is reappraisal of the first part of adulthood and redirection and change as determined by this reexamination of earlier life choices. The transition may be relatively easy or very difficult, but it is characteristic of this phase to either make new life choices or reaffirm old choices.

The next phase is the settling down phase. Here the individual establishes his or her niche in society (eg, occupation, family, and community) and works toward advancement. This is followed by the midlife transition phase, which consists of reappraisal of the settling down period and dealing with and resolving polarities between the individual’s sense of him- or herself and the world. Levinson offers some examples of polarities such as young/old, destructive/creative, masculine/feminine, and attachment/separateness. The most important task is coming to terms with the real or impending biological decline accompanied by the recognition of his or her own mortality as well as societal attitudes that denigrate or devalue the status of middle age in favor of youth.

The next phase is another structure-building period. Having faced the polarities of the midlife transition, the person now makes new choices or reaffirms old ones. As an individual moves to the end of this period, yet another structure-changing phase is entered as the person once again reevaluates his or her life upon entry into “old age.”

Positive aging is out of the hands of rehabilitation therapists. However, the more therapists understand stages that men and women are likely to undergo as they age, the more responsive they can be to persons in their care. Developing a meaningful context within which the transformations of aging can be understood will be aided by information offered by all who work with older adults, especially those involved in their day-to-day rehabilitation.

COGNITIVE CHANGES IN LATE LIFE

Are cognitive declines inevitable consequences of aging? Is there a continuum from normal aging to pathological states such as Alzheimer dementia? According to the Seattle Longitudinal Study, only 20% of adults exhibited reliable age-related decline from 60 to 67 years of age, 36% experienced decline between 67 and 74 years, and over 60% of older adults showed a decline between the ages of 74 and 81 years.28 Community surveys indicate that over 50% of people over age 60 report memory problems,29 and the incidence is even higher in people referred to a geriatric screening program.30 However, normative studies are difficult to accomplish without contaminating the data to a certain degree. Normative studies of older adults without longitudinal follow-up typically have included individuals with preclinical dementia who have begun to decline cognitively but still perform within normal limits on neuropsychological testing.31,32 This results in an underestimation of the true level of normal cognitive performance. Estimates of variability are inflated due to the mix of individuals with and without preclinical dementia, and it is difficult to identify healthy older individuals who have unrecognized preclinical dementia.32

Table 4-1. Changes in Cognition With Normal Aging

COGNITIVE ABILITIES | CHANGES |

| Intelligence | Performance scale of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale shows more decline than the verbal scale |

| Problem-solving | Decline delayed until late sixth decade |

| Older adults may be less proficient on laboratory tests | |

| Memory | |

Sensory | Little if any decline |

Short-term | No decline |

Long-term (secondary) | Some decline, deficits in encoding processes, deficits more pronounced in free recall than recognition |

Long-term (remote) | Little decline |

Psychomotor skills | Decline may begin in the early 50s |

Information processing | Decline may begin in the early 50s |

Verbal skills | Declines do not occur until after age of 80 if at all |

Abstract reasoning | Mental flexibility or set shifting in reasoning task have been shown to decline |

Adapted from Riley.33

There is a significant variability in the pattern and rate of change in cognitive abilities. Verbal abilities reach peak performance in the sixth and seventh decades of life, and reliable age-related decline does not occur until the middle of the eighth decade.28 Table 4-1 summarizes the changes in cognition generally associated with normal aging.33

Memory

Memory has been extensively studied for many years; yet, no definitive conclusions have been obtained.34,35 Some studies show a decrease in memory with age, while others show no change.34,35 Studies agree that older persons do have poorer techniques for organizing new information into a usable form that will impact information retrieval.36 In addition, older persons perform better on more familiar memory tasks.37 Older adults perform at a lower level on most memory tasks and tend to use more external (physical) rather than internal (mental) memory strategies.38

One’s sense of competence and confidence related to a specific performance in a given domain have also been found to affect memory. Some studies have found a lack of correlation between self-reports and cognitive performance.39 This is likely due to expectations about aging and memory loss rather than declining abilities. A self-perceived negative assessment of memory functioning was found to be associated with greater concern about developing disease.39 If memory loss is not viewed as a problem by older adults themselves, it does not interfere with their level of functioning and the achievement of everyday goals, and cognitive performance scores remain within normal ranges. There is also evidence that learning occurs into advanced age.39 Of interest, the neurodynamic changes underlying memory and cognitive changes show relatively random spiking times of individual neurons. It has been shown that these changes associated with aging demonstrate a reduced firing rate of excitatory neurons, resulting in the probability of a decrease in recall and short-term memory.39 This stochastic dynamic approach provides new ways of understanding and potentially treating the effects of normal aging on memory and cognitive functions.

RX

Treatment techniques for memory loss include the use of classes and educational strategies to assist with memory. Classes in self-esteem, accurate record keeping, and the use of mnemonic devices can be helpful. Two additional hints in helping memory are to keep techniques as familiar as possible and to develop some type of reward system. (Refer to Chapter 18.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree