(1)

Department of Pathology Beckley Veterans Medical Center (West Virginia), McGuire Veterans Medical Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

Review of Pertinent Physiology and Histology of the Skin

Keratinocytes

The important barrier function of the epidermis is supported by the epidermal appendages such as the hair follicles and sebaceous and sweat glands. The epidermis contains a basal layer of proliferative keratinocytes that adhere to the underlying basement membrane. In the process of differentiation, the committed basal cells detach from the basement membrane and progress through different stages and form three distinctive layers: the spinous, the granular, and the stratum corneum. The molecular mechanism underlying this complex process is still poorly understood [1, 2].

Three pools of keratinocyte stem cells have been identified. They are located in the interfollicular basal layer, the hair follicle bulge, and the sebaceous gland. Under normal circumstance, they are responsible for the homeostasis of their respective home structures. However, each of them has the potential to produce the other two structures [2–5]. Furthermore, recent data indicate the existence of a fourth source of keratinocyte stem cells in the sweat glands [3, 4].

Dermal Fibroblasts

The epidermal appendages are generated through a complex inductive influence of the dermis which determines the nature of the ectodermal differentiation. The adult dermal stroma contains at least three different types of fibroblasts in the adults [6–8]. They include the CD10-positive, CD34-positive, and factor XIII-positive fibroblasts. The CD10-positive cells are present in the periadnexal stroma. The CD34-positive cells are probably bone marrow derived, located perivascularly. They probably form a complex network as the intestinal pericryptal fibroblasts and play an important role in antigen presentation and host immune reactions. Similar in what is seen in the GI surgical pathology I which loss of the pericryptal cells is indicative for malignancy, loss of CD34-positive cells is an important feature of invasive cutaneous malignancies including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma. It signifies the destruction of the dermal immune barrier.

Factor XIII-positive fibroblasts are predominantly present in the papillary dermis surrounding the vasculature and sweat glands. Dermatofibroma cells show reactivity for factor XIII, whereas tumor cells in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans are positive for CD34. The characteristic storiform pattern of the latter might reflect the cells’ property to form a three-dimensional immunological meshwork.

Melanocytes

Melanocytes are charged with the important task of shielding the organism from injurious UV lights. They are derived from the neural crest which migrates to the dermis before settling down in the epidermis and hair follicles. This important migratory property is reflected in many melanocytic lesions, both benign and malignant.

In the epidermis, they form a symbiotic relationship with the keratinocytes in the form of so-called melanokeratinocyte units [9, 10]. In the unit, the differentiated melanocytes are located in the basal layer (in a ratio of 1:5 with the basal cells), and through their cellular processes, each interacts with proximately 36 keratinocytes. In contrast to keratinocytes which are rapidly replaced, normal melanocytes have a slow turnover rate which is tightly controlled by the keratinocytes through various mechanisms.

Stromal Invasion in the Context of Cutaneous Dermis

Due to the unique histological arrangement of the dermal appendages, most of benign epithelial lesions are surrounded by dermal tissue. Benign melanocytic nevoid cells also have the natural propensity to penetrate the dermis. Therefore, the criteria for dermal invasion need to be strengthened if the concept is to remain diagnostically relevant.

In this chapter, we propose a set of key features for dermal invasion for four major categories of cutaneous malignancy: squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, eccrine carcinoma, and melanoma. Importantly, the lack of CD34 fibroblasts might represent a universal yardstick in cutaneous surgical pathology [11, 12].

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Dyskeratosis

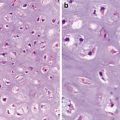

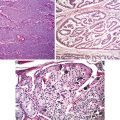

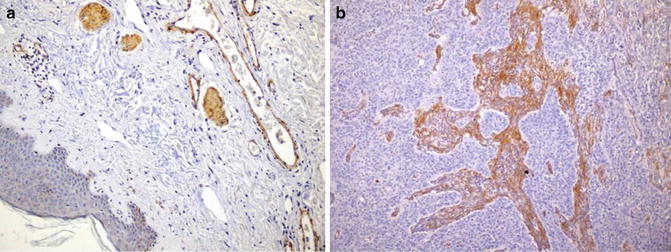

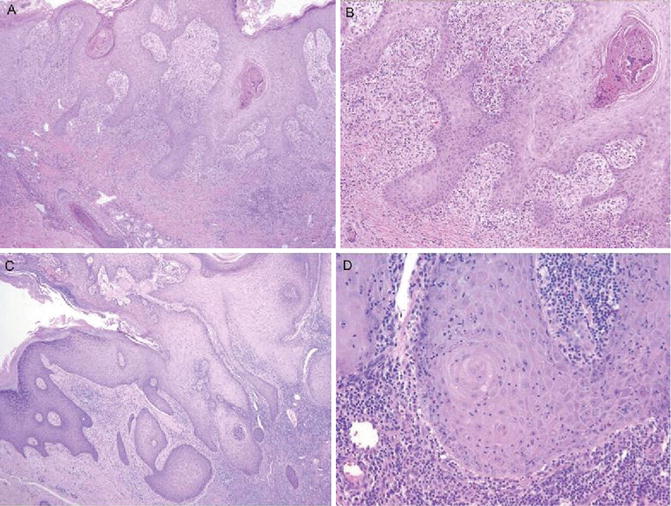

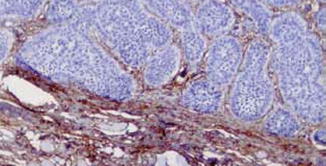

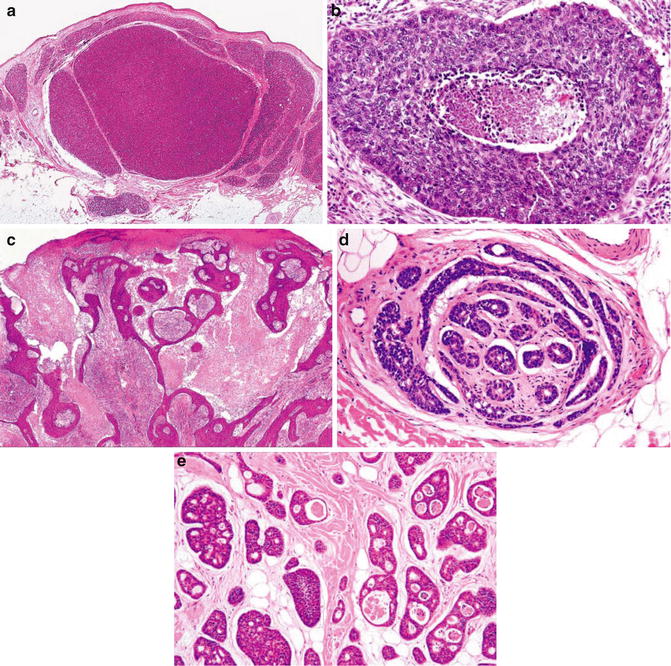

Stromal Invasion (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2)

Fig. 1.1

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Stromal invasion by irregular nests (Pathology of the Skin, Elsevier/Mosby, 2005; Dermatology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

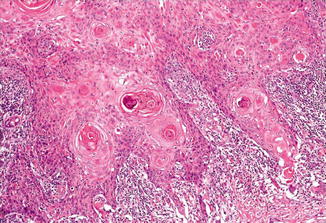

Fig. 1.2

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Note dyskeratotic cells (Pathology of the Skin, Elsevier/Mosby, 2005 with permission)

Discussion

Dissimilar to mucosal squamous cell carcinomas, cutaneous squamous carcinomas are mostly UV light related. Even though the stem cells in the adnexal structures have the potential to give rise to epidermis, the adnexal structures apparently manage to prevent the involvement by the dysplastic squamous cells. This is in contrast to the situation in the squamous mucosa in which dysplastic cell frequently involves the underlying glandular structures mimicking invasive carcinoma.

The bland squamous cells of well-differentiated squamous cells demonstrate dyskeratosis which is characterized by early keratinization (keratin pearls in the basal and parabasal layers) and excessive cytoplasmic keratinization. It is not to be confused with squamous eddies and horn cysts which are present in seborrheic keratosis and trichilemmal or trichoblastic lesions, respectively.

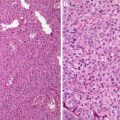

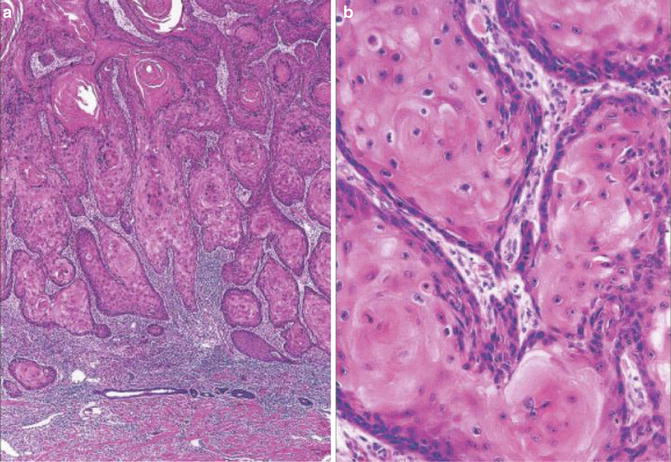

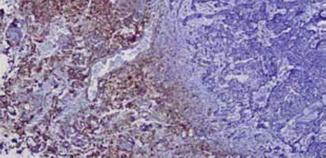

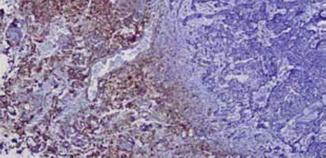

Identification of stromal invasion of the squamous cell carcinoma can be tricky. On the one hand, verrucous and keratoacanthoma variants have a well-circumscribed contour. On the other hand, several benign squamous proliferations appear to invade the dermis. Familiarity with their histological presentations is valuable in avoiding overdiagnosis. Like in other locations, a panel of immunostainings (p53, MMMp-1, and ki67) may be useful. Recent evidence indicates that the stroma of squamous cell carcinoma lacks CD34 fibroblasts (Fig. 1.3). Instead, it has increased expression of SMA-positive myofibroblasts (Fig. 1.4).

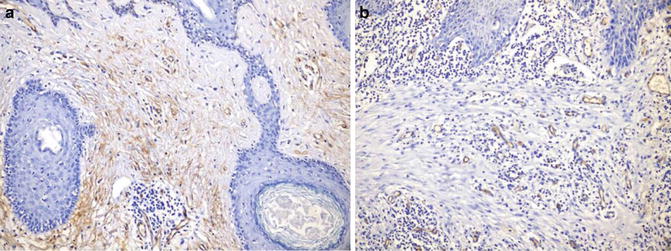

Fig. 1.3

Stroma of squamous cell carcinoma lacks CD34+ fibroblasts (b). Benign dermis contains abundant CD34+ fibroblasts (a)

Fig. 1.4

Stroma of squamous cell carcinoma contains SMA-positive fibroblast (b). Benign dermis lacks SMA-positive fibroblasts (a)

Differential Diagnosis

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia typically involves both the epidermis and the follicular infundibular and even acrosyringia. In fact, the acanthotic downgrowths have been thought to represent expanded follicular infundibula. Appro-priate differentiation from well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma would require the appreciation of the underlying inflammatory process and shape of the invasive components and their connection to the surface and shape (jagged pointed tips and a broad base connected to the surface) (Fig. 1.5). In addition to the usual immunostaining panel (p53, MMP-1, and Ki67), immunostainings for CD34 and SMA seems to be valuable [13–15]. The stromal cells of invasive squamous carcinoma lack reactivity for CD34, whereas SMA stain lights up haphazardly arranged myofibroblasts (desmoplasia).

Fig. 1.5

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Note broad bases and lack of dyskeratosis (American Journal of Dermatopathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012 with permission)

Prurigo Nodularis

It shows hyperkeratosis with acanthosis in addition to the accompanying pseudoepitheliomatous proliferation. Helpful clues include spongiosis, inflammatory cells, and prominence of blood vessels and nerve endings.

Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis (Inverted Follicular Keratosis)

The lesion presents as an endophytic proliferation of squamous and basaloid cells. Characteristi-cally, it contains many squamous eddies which are different from the horn pearls of well-differentiated squamous cells in that they are well circumscribed, small in size, and numerous in number. Frequently, the downgrowth can be seen to originate in the vicinity of a follicle.

Tricholemmoma and Desmoplastic Tricholemmoma

Desmoplastic tricholemmomas can have irregular downgrowth of bland epithelial cells into a sclerotic or desmoplastic stroma. Attention to the superficial portion usually reveals changes typical of a tricholemmoma. Tricholemmomas present as lobules with peripheral columnar cell palisading and a distinct thick basement membrane. Cytoplasmic clearing involves variable number of cells.

Pilar Sheath Acanthoma (Proliferating Pilar Tumor)

The proliferating squamous lobules show glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm. Portion of the tumor can show peripheral palisading, a thickened basement membrane, and cytoplasmic clearing. Abrupt change into keratin production is another feature of the central cells. Sometimes, squamous proliferations are seen to radiate from the wall of the pilar cysts into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Some degree of cytological atypia as well as individual cell keratinization can be seen.

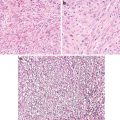

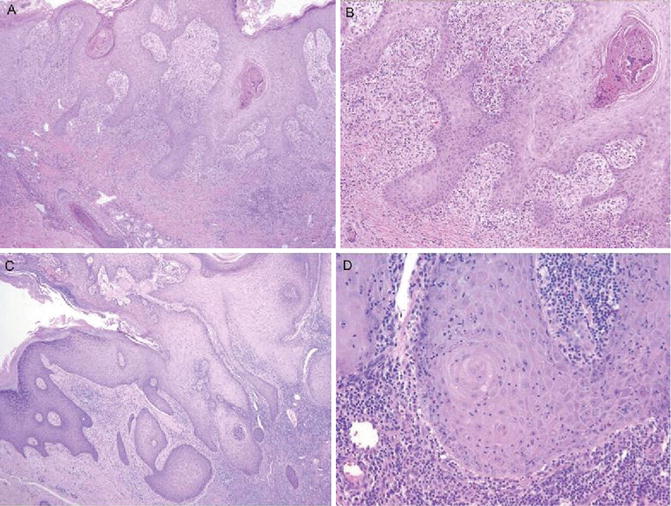

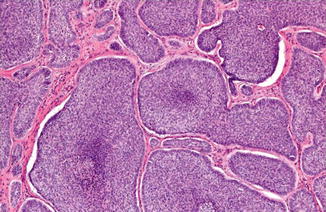

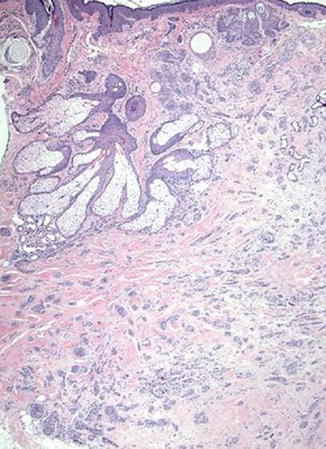

Key Morphological Features of Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basaloid cell morphology

Peripheral palisading and clefts (Fig. 1.6)

Fig. 1.6

Basal cell carcinoma with basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting

Discussion

Even though there is evidence for its interfollicular origin, cutaneous basal cell carcinomas have been shown to manifest histochemical differentiation to hair follicles. Actually, the 2006 WHO Classification has placed it under the adnexal tumor category.

Basal cell carcinomas can be divided into two major subcategories: differentiated and undifferentiated. The differentiation is frequently toward adnexal components. Even in the keratotic subtype, the keratinization shows pilar differentiation in the form of parakeratosis and horn cysts.

At microscopic level, the basaloid cells resemble the normal epidermal basal cells and basal cells in squamous cell carcinoma. Significant differences are, however, evident at the ultrastructural level. The basaloid tumor cells have defective expressions of hemidesmosomes, anchoring filaments and integrins, as well as bullous pemphigoid antigen [16–18]. These changes might be the underlying mechanism for the characteristic clefting around the tumor clusters. This characteristic clefting has long been discounted as a processing artifact. However, recent evidence shows that the clefts correspond to the low-refractility areas seen in vivo by reflectance confocal microscopy [19]. These ultrastructural defects indicates that the basal cell carcinoma cells have problem in establishing close attachments with the stromal components and are consistent with the inability of the tumor to metastasize.

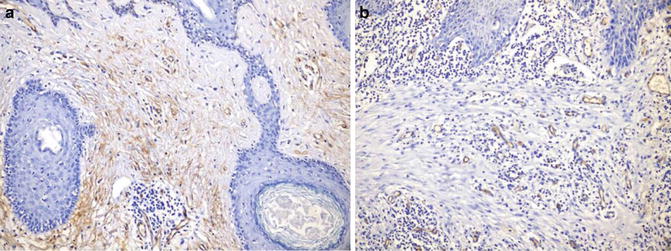

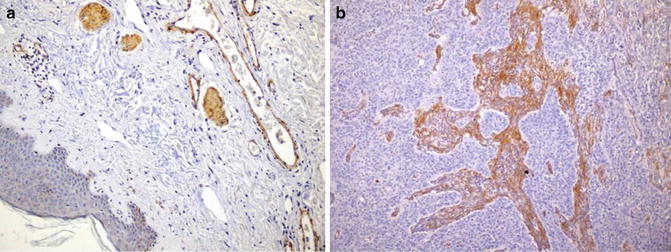

Basal cell carcinoma cells seem to induce a parallel proliferation of spindle cells around the tumor nests, and the spindle cells show partial differentiation toward the follicular connective sheath [20]. However, the cells seem to lack CD10 and CD34 reactivity (Fig. 1.7). Instead, the malignant epithelial cells demonstrate diffuse staining for CD10 [18]. This important feature can be very useful in the differential diagnosis.

Fig. 1.7

Stroma of basal cell carcinoma lacks CD34+ fibroblasts

Differential Diagnosis

Trichoepithelioma, Trichoblastoma

Trichoepitheliomas are composed of well-circumscribed, symmetrical lesions composed of basaloid cells and horn cysts with trichilemmal keratinization. Even though peripheral palisading is evident, there is no stromal clefting. The epithelial cells are positive for CK20. In contrast to the diffuse Bcl-2 staining in basal cell carcinoma, only the peripheral cells show reactivity. The surrounding stroma is typically cellular and CD34 positive (Fig. 1.8).

Fig. 1.8

Stroma of trichoepithelioma contains CD34+ fibroblasts

Trichoblastomas differ from trichoepitheliomas by their small size, location, and lack of keratinizing horn cysts.

Seborrheic Keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis is composed of basaloid and squamous cells and can manifest in six different histological patterns. They all lack peripheral palisading and stromal clefting.

Eccrine Poroma

Eccrine poromas consist of uniform basaloid cells in cords and columns extending down to the dermis. Occasional narrow ductal and cytoplasmic lumen formation and cytoplasmic clearing are evident. There is neither peripheral palisading nor clefting. The intracytoplasmic lumina and ducts are positive for CEA, EMA, and PAS.

Basaloid Follicular Infundibulum Tumor and Basaloid Follicular Hamartoma

Basaloid follicular infundibulum tumors present as horizontal, fenestrated, pale squamous cell proliferation with multiple connections to the epidermis. There is peripheral palisading. However, the tumor cells have more cytoplasm and lack stromal clefting.

Basaloid hamartoma has both basaloid and squamous proliferations with interconnecting narrow bands emanating from the hair follicle infundibula. Occasional horn cysts can be seen. The cells show peripheral palisading, but lack clefting.

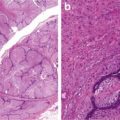

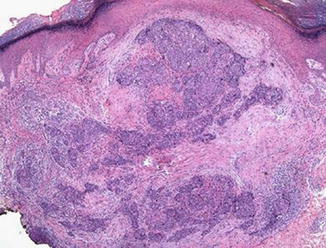

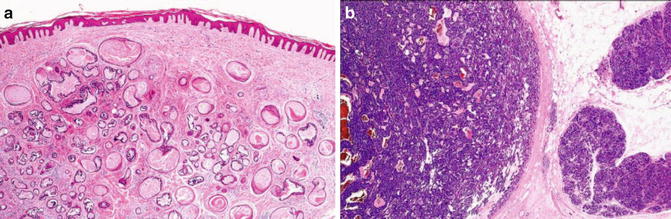

Key Morphological Features of Well-Differentiated Eccrine Carcinoma

Silhouette of asymmetry

Epithelial–stromal clefting, ill circumscription, non-vertical orientation (Figs. 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, and 1.12)

Fig. 1.9

Microcystic carcinoma. Silhouette of asymmetry (Dermatology, Elsevier/Saunders, 2011 with permission)

Fig. 1.10

Porocarcinoma. Silhouette of asymmetry and poor circumscription (Modern Pathology, Nature Publishing Group, 2006 with permission)

Fig. 1.11

Adnexal carcinoma. Epithelial–stromal clefting (Pathology of the Skin, Elsevier/Mosby, 2005 with permission)

Fig. 1.12

Benign adnexal tumor. Note well circumscription, symmetry, and V-shaped contours (Pathology of the Skin, Elsevier/Mosby, 2005 with permission)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree