(1)

Department of Pathology Beckley Veterans Medical Center (West Virginia), McGuire Veterans Medical Center, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

Thyroid Gland

Key Morphological Features of Papillary Carcinoma

Highly infiltrative borders

Predominantly branching papillary structures composed of cells with unique nuclear changes (nuclear enlargement, overlapping, crowding, chromatin clearing, irregular nuclear contours, nuclear grooves, and pseudoinclusion) (Figs. 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, and 9.4)

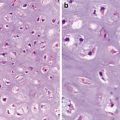

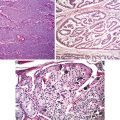

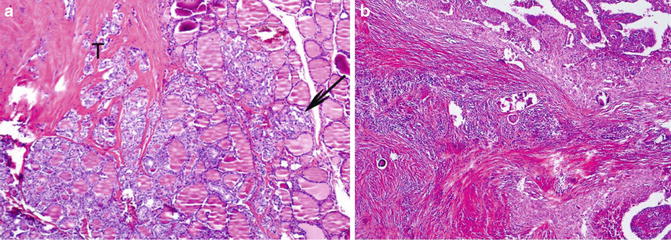

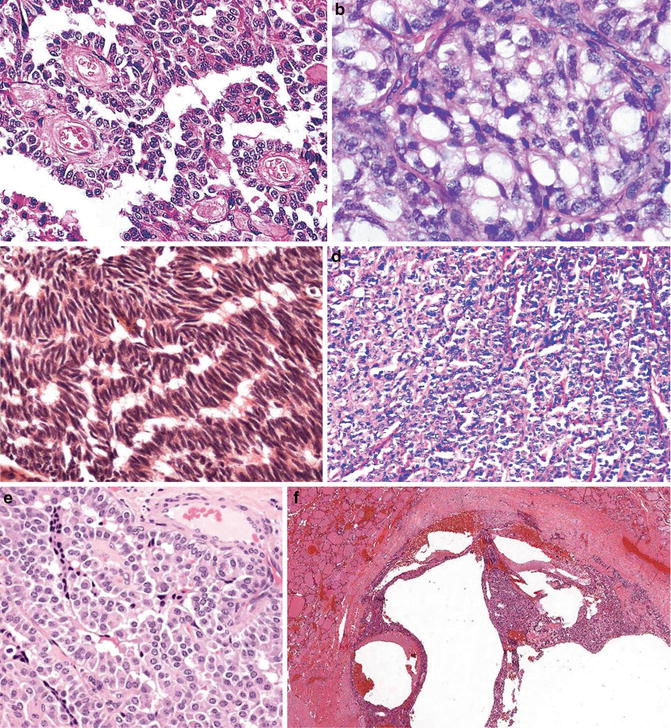

Fig. 9.1

Papillary carcinoma. Infiltrative growth pattern (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Fig. 9.2

Papillary carcinoma. Infiltrative border (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

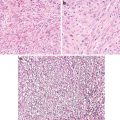

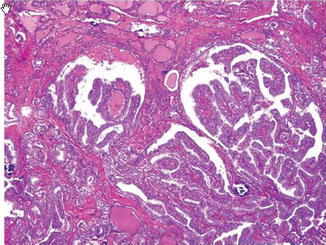

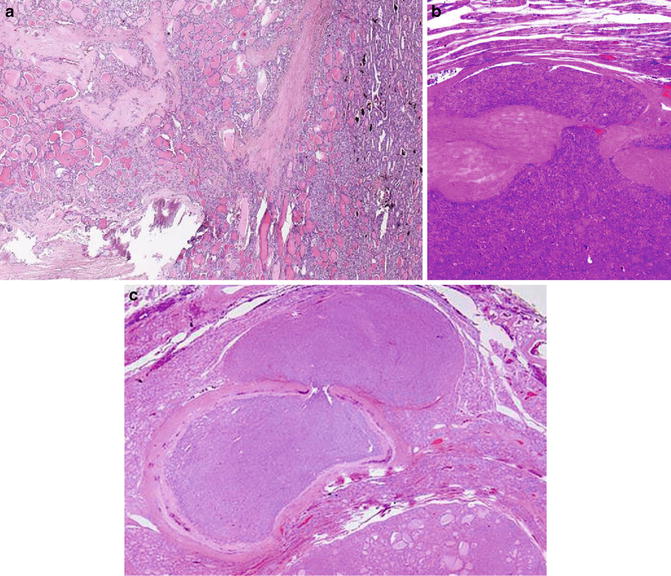

Fig. 9.3

Papillary carcinoma with branching papillary structures (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

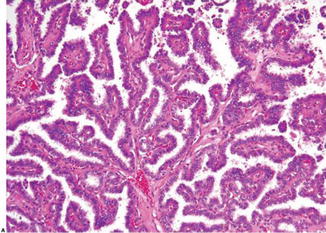

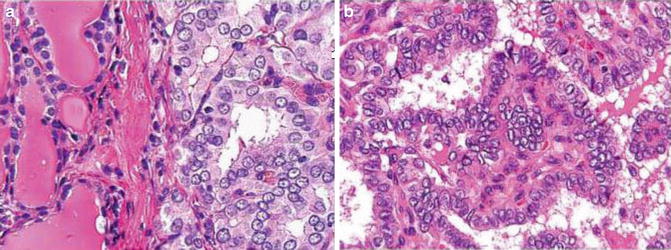

Fig. 9.4

Characteristic nuclear feature of papillary carcinoma (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

Papillary carcinomas are the most common thyroid malignancies. If the encapsulated follicular variant is left out as a distinct entity (precursor or borderline) as they show molecular and immunochemical features between follicular adenomas and papillary carcinomas, it is safe to say that vast majority of papillary carcinomas lack a capsule (exception: the rare macrofollicular variant) which is the trademark of follicular adenomas and carcinomas [1, 2]. Instead, they have infiltrative borders.

The characteristic morphological of papillary carcinomas is papillae admixed with a variable portion of follicular structures. The neoplastic papillary structures are characterized by a branching structure composed of a delicate fibrovascular core lined by a one layer of atypical cells. The cliché “not all papillary carcinomas have a papillary growth pattern and not all papillary patterned thyroid lesions are papillary carcinoma” serves as a useful reminder for surgical pathologist but has led to the de-emphasis of the evaluation of the papillary structures in thyroid pathology. Actually the papillary structures in papillary carcinoma are more branching and contain more fibrovascular tissue than the simpler nonbranching papillae present in benign thyroid lesions such as nodular goiters and follicular adenomas [3]. The lining cells of the former are arranged in a nonpolar, haphazard pattern while the latter contains cells with basally located nuclei [3].

It is known that papillary carcinomas show wide variation not only in growth pattern but in cell morphology as well. The only unifying characteristic feature among all of papillary variants is the nuclear changes. They include nuclear enlargement and crowding and overlapping, nuclear clearing, irregular nuclear contours, nuclear grooves, and nuclear pesudoinclusion. Studies have attributed these changes to RET/PTC mutations with the nuclear translocation of beta-catenin playing an important role (with the help of vimentin amassed adjacent to the nuclear membrane) [4, 5].

Because many other benign lesions can have focal nuclear changes similar to those of papillary carcinomas and currently there is no consensus as to how many of them and how extensive they should be in order to qualify for papillary carcinoma, it is highly advisable that other features such as lack of encapsulation, infiltrative borders, fibrous bands, complexity of papillae, as well as clinical information are taken into consideration (Fig. 9.5). In difficult cases, several promising immunostainings could be used (galectin-3, HBME-1, CITED1, and vimentin).

Fig. 9.5

Papillary carcinoma with prominent fibrosing bands (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Differential Diagnosis

Benign Papillary Proliferation

The papillary structures are usually nonbranching. The cells maintain polarity and lack the typical nuclear features.

Lymphocytic/Autoimmune Thyroiditis

The infiltrative lymphocytes can induce nuclear clearing and intranuclear grooves and focal fibrosis. To distinguish a micropapillary carcinoma from reactive changes associated with thyroiditis, it is essential to choose areas lacking inflammatory infiltrates and require that all the nuclear changes are present before making a diagnosis of papillary carcinoma arising from lymphocytic/autoimmune thyroiditis

Grave’s Disease and Toxic Nodular Goiter

They may have papillary formations with cells exhibiting chromatin clearing, intranuclear grooves, and pesudonuclear inclusions. However, the former is a diffuse lesion involving the whole gland with areas of lymphocytic infiltration. Close examination of the papillae reveals infoldings within follicles. Complex arborization is not the theme. The lining cells maintain their polarity and lack nuclear overlapping. Similar changes can be seen in toxic nodular goiters.

Hyalinizing Trabecular Adenoma

Characterized by a trabecular growth pattern with intermixed hyaline material, the tumor cells show many nuclear changes of papillary carcinoma. Papillary carcinomas, however, rarely present as a trabecular growth pattern containing prominent stromal hyalinization. In difficult cases HBME-1 and galectin-3 stains can be employed to make the distinction.

Hurthle Cell Lesions

They may contain nuclear elongation and nuclear grooves, and some degree of nuclear clearing and contour irregularity can be seen. Hurthle cells contain centrally located round nuclei with prominent central nucleoli but lack nuclear overlapping and crowding. To make a diagnosis of oncocytic papillary carcinoma distinction, the nuclear feature should be diffuse and unequivocal.

Instrumentation and Frozen Preparation

FNA and frozen sections are known to induce nuclear changes mimicking papillary carcinoma. Fortunately these changes are usually focal and confined to the areas showing the other associated changes such as hemorrhage, infarction, fibrosis, and vascular proliferation. It is therefore important to shun those areas in the evaluation of nuclear features. Frozen section of thyroid neoplasia is largely discouraged since the evaluation of capsular and/or vascular invasion and nuclear features is compromised.

Key Morphological Features of Follicular Carcinoma

Encapsulation

Capsular and/or vascular invasion (Figs. 9.6 and 9.7)

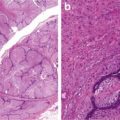

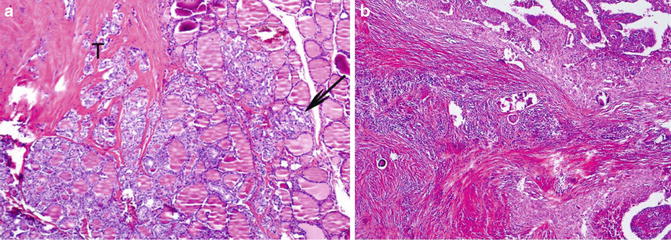

Fig. 9.6

Follicular carcinoma. Capsular invasion (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Fig. 9.7

Follicular carcinoma. Vascular invasion (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

In stark contrast to the emphasis on nuclear features in diagnosing thyroid papillary carcinomas, both nuclear and cellular features are virtually ignored in the distinction between follicular adenomas and carcinomas.

Instead, capsular or vascular invasion has been promulgated as the only criterion. Therefore, those follicular lesions with worrisome morphological changes but short of solid evidence for invasion should be called adenomas. The worrisome changes include necrosis, increased mitotic figures, high cellularity, nuclear atypia, spindle shape, and even thick capsule with entrapped benign cells. Like follicular adenomas with bizzare nuclei, those follicular lesions behave in a benign fashion. Necrosis and mitotic activity have limited use in thyroid pathology. The first use of them is in the differentiating well-differentiated carcinomas (papillary and follicular) from poorly differentiated carcinomas which can present with papillary and follicular patterns and even nuclear features characteristic of papillary carcinomas. They are separated out by frequent necrosis, mitotic activity, and convoluted nuclei. The other use is separating widely invasive follicular carcinomas and medullary carcinomas from anaplastic carcinomas. The latter is characterized by high-grade nuclei, brisk mitotic figures, and necrosis.

While partial capsular invasion has been accepted by some experts, the stringent through-and-through criterion is endorsed by most of the experts [3]. By definition, capsular invasion requires penetration of the full thickness of the tumor capsule (not the thin capsule of the gland) [6]. The rationale behind adopting such a stringent criterion is to sieve out pseudoinvasion. For example, during the capsular formation of follicular adenoma, benign follicles might be entrapped by the fibrous tissue. In evaluating a small nodule outside the main tumor, a connection of the invasive front to the main tumor mass should be traceable. If deeper sectioning reveals no connection through a defect in the capsule, the nodules are more likely to be a separate lesion. The through-and-through criterion also avoids calling the folding of capsule (due to sectioning) capsular invasion.

The invasion most commonly manifests as a mushroom- or hooklike structure. When the tumor becomes widely invasive, the tumor capsule might not be easily recognized. In a manner similar to that of lung adenocarcinomas, the invasive fronts of the follicular carcinomas are rimmed by fibrotic tumor stroma preventing direct contact with the normal tissue [3].

Similarly, strict criteria should be adhered to in the evaluation of vascular invasion in follicular lesions. Because the normal thyroid gland and follicular neoplasms have a very rich endocrine vascular network with little fibrous tissue between the epithelial cells and blood vessels and the endothelial layer is thin and fenestrated, pseudo-vascular invasion is a common occurrence [7, 8]. Therefore, vessels in the capsule or immediately beyond the capsule should be selected for evaluation. To be called vascular invasion, the tumor clusters must be attached to the vascular wall and covered with a layer of endothelial cells.

Follicular carcinomas are thought to be a well-differentiated malignancy of the thyroid gland, and their clinical outcome correlates well with the extent of invasion irrespective of the degree of morphological differentiation toward normal follicles [3]. When papillary carcinomas are brought into the picture for contemplation, one could not help wondering why these two well-differentiated entities possess contrasting features. For instance, follicular carcinomas have thick capsules but only minimal amount of mesenchymal stroma. Even when the tumor cells have penetrated through the capsule, tumor cells do not come into direct contact with thyroid parenchyma. When the tumor metastasizes, follicular carcinoma cells prefer blood vessels even though abundant lymphatics are present [9]. Papillary carcinomas, on the other hand, lack encapsulation but contain a conspicuous fibrose stroma and infiltrative borders. For tumor dissemination, they favor lymphatics for dissemination. Let alone the characteristic nuclear features discussed in the previous section.

Moreover, follicular and papillary carcinomas seem to thrive in different bioenergetic states [10–12]. Follicular carcinomas have unchanged GLUT-1 level and express no caveolin-1, whereas in papillary carcinomas GLUT-1is overexpressed at both protein and mRNA levels and caveolin-1 is expressed in both tumor and stromal cells. Presumably, little cancer stroma metabolic coupling exists for follicular carcinomas as there is little stroma to start with and the cells are more reactive to TSH which could affect glucose uptake by GLUT-1 translocation and angiogenesis. Papillary carcinomas on the other hand are more likely to take advantage of their abundant stroma in forging a metabolic alliance for tumor growth. In this coupling the glycolytic stromal cells generate high levels of lactate to support mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the adjacent tumor cells. However, if the coupling indeed exists, (an) unconventional mechanism(s) should be involved because in many other types of cancers, loss of caveolin-1 rather than overexpression of it allows autophagy and mitophagy with resultant aerobic glycolysis in the stromal cells [13, 14].

The fetal cell carcinogenesis theory and cytogenetics offer a plausible explanation for the contrasting features of the two entities. According to the fetal cell carcinogenesis theory, follicular carcinoma cells are better differentiated than papillary carcinoma cells with the former deriving from prothyrocytes and the latter thyroblasts [15]. The presence of RET/PTC rearrangement and BRAF mutations prevent the thyroblasts from differentiation and the PAX8–PPAPr rearrangement hinders the maturation of prothyrocytes into thyrocytes. The thyroblast-like cells in papillary carcinomas apparently retain some important features of fetal thyroblasts which face the daunting challenge of navigating the mesenchyme and reaching the final destination of the lower neck from the base of prospective tongue. In doing so, the migrating thyroblasts need to develop a close working relationship with the fetal mesenchyme and yet hold themselves together. This feature is accomplished presumably through a collective cell migration mechanism in which cell-to-cell adhesion does not have to be compromised [16]. Thus, the characteristic features of the papillary carcinomas such as infiltrative behavior, abundant accompanying stromal response, and propensity for lymphatics in dissemination can be explained by their retained thyroblastic properties. In line with the theory, papillary carcinoma cells express on fFN, vimentin, and claudin-10, all of which are negative in follicular carcinomas [11, 15].

Capsule formation is apparently a later event during the organogenesis. It coincides with vasculogenesis, cell growth, maturation into prothyrocytes and thyrocytes, and loss of cell motility. It is presumable that through a similar mechanism to that operating in the organogenesis of other highly specialized organs such as the liver, lungs, and kidneys, the maturing follicular cells break up with the mesenchyme and diminish the presence of it in the parenchyma to the minimum (except for a rich network of capillaries surrounding each follicle and a peripheral capsule). In line with the fetal cell carcinogenesis theory, follicular carcinoma cells are more responsive to TSH and have more TPO activity than papillary carcinomas [17–19]. They still maintain the capability to induce sinusoidal angiogenesis and capsule formation and manifest a pushing border (decreased mobility) and blood vessel preference for dissemination [20, 21].

Differential Diagnosis

Follicular Adenoma

They lack unequivocal capsular or vascular invasion even though they can show many concerning features which in other tissues are frequently construed as evidence of malignancy. The presence of them should alert the pathologist to search for signs of invasion by submitting more sections and getting deeper levels.

The awareness of neuroendocrine atypia in the form of adenoma with bizarre nuclei helps alleviate one’s concern for possible anaplastic carcinoma in which highly atypical cells present in sheets with associated frequent mitotic and tumor necrosis.

Nodular Goiter

Believed to arise from mature thyrocytes as a result of complex interplay between susceptible genes and environmental factors, nodular goiters usually are multiple nodules with no or only a partial capsule. In contrast to the uniform monotonous growth pattern of the follicular neoplasms with minimal fibrosis, they are characterized by variously shaped and sized follicles composed of cells with variable cell shapes and frequent fibrosis and hemorrhage. Sanderson pollsters and even papillary infoldings can be seen in large follicles.

Papillary Carcinoma

Typical papillary carcinomas are easily differentiated from follicular carcinomas due to their contrasting features. Three variants of papillary carcinoma, however, are potentially troublesome.

As discussed in the papillary carcinoma section, the encapsulated follicular variant probably represents a borderline or precursor lesion. While many of them have characteristic nuclear features, in some cases the changes are focal. In these cases, areas lacking the features are intermixed with typical areas. This is in contrast to papillary carcinomas arising in a follicular adenoma or hyperplastic nodule in which the carcinomatous component presents as a well-circumscribed focus separated from the background lesion.

The diffuse follicular variant resembles follicular neoplasms in many ways.. They show a predominantly small follicular pattern with inconspicuous fibrosis and infrequent psammoma bodies. The tumor cells prefer to spread via the vascular rather than lymphatic route.

Strict adherence to the nuclear criteria steers toward the right diagnosis.

Rare cases of the macrofollicular subtype can be easily missed because they are encapsulated and contain large follicles with abundant colloid, and sometimes the characteristic nuclear features are present focally.

Key Morphological Features of Medullary Carcinoma

Plethora of cytological and histological appearance, often in one single tumor

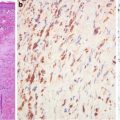

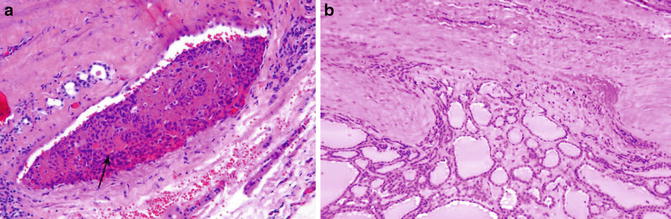

Salt–pepper nuclear texture (Fig. 9.8)

Fig. 9.8

Medullary carcinoma. Different growth patterns (Diagnostic Pathology and Molecular Genetics of the Thyroid: A comprehensive Guide for Practicing Thyroid Pathology, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009 with permission)

Discussion

Medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland represents a unique neuroendocrine tumor characterized by its protean cytological and architectural features [22]. This plethora of cytological and histological presentations even surpasses what is seen in papillary carcinomas, and they are usually seen in one single tumor. Medullary carcinoma cells can be round, ovoid to polyhedral, spindle, and plasmacytoid. Typically, cytoplasm is finely granular; however, clear cells and mucin-secreting, oncocytic, and even melanin-containing cells can be present. The typical neuroendocrine nuclear feature is often appreciated. Growth patterns include solid sheets, nests separated by fibrous stroma which frequently contain amyloid material, and calcifications and papillary, follicular/glandular structures.

The tumor cells are positive for calcitonin and CEA providing a very useful tool in the differential diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

C Cell Hyperplasia

The distinction is mainly between C cell hyperplasia and micromedullary carcinoma. Micromedullary carcinoma is differentiated from C cell hyperplasia by breakage of follicular basement membrane. One important clue to the presence of basement membrane breach is fibrosis around nests.

Metastatic Tumors

Primary and metastatic neuroendocrine tumors other than medullary carcinoma are rare in the thyroid gland. When the question arises, immunostainings for CEA and calcitonin can be helpful. Metastatic renal cell carcinomas can resemble medullary carcinoma, both architecturally and cytologically, and require utilization of immunostainings for vimentin and calcitonin.

Follicular Carcinoma

Some medullary carcinoma cells have follicular formations or oncocytic changes, thus mimicking follicular carcinoma. When follicular carcinomas present as solid or trabecular growth pattern or clear cells with inconspicuous colloid, medullary carcinoma enters into the differential diagnosis. The presence of neuroendocrine nuclear feature, prominent stroma with amyloid material and calcifications, and lack of a thick capsule cinch the diagnosis. In difficult cases, calcitonin and thyroglobulin immunostainings might be needed.

Papillary Carcinoma

Medullar carcinomas resemble papillary carcinomas in many ways. They lack encapsulation but contain a prominent fibrose stroma. Papillary or pseudopapillary, follicular structures and even nuclear inclusions can be present. Interestingly, tumor cells show propensity for both lymphatic and vessels in dissemination. However, to be called papillary carcinoma, more nuclear features are needed as discussed in the section for papillary carcinomas.

Anaplastic Carcinoma

Anaplastic carcinomas of the thyroid superficially resemble medullary carcinomas in that they also manifest a wide variety of cellular and architectural appearances which are often seen within the same tumor. They are characterized, however, by high-grade nuclear feature, extensive necrosis, brisk mitotic activity, and a widely infiltrative pattern.

Salivary Gland

Review of Pertinent Histology and Physiology

The major salivary glandular unit consists of the acinus, intercalated duct, striated duct, and excretory duct. The overall pattern of the salivary gland unit is a bilayered structure made up by luminal and abluminal cells. The abluminal cells in the first two parts are myoepithelial in nature and in the last two parts are basal. The luminal cells can also be divided into two types: serous and mucinous with the proportion of each type varying at different parts.

Salivary gland epithelial cells have a slow turnover rate (>60 days). It is believed that under normal conditions, the adult epithelial cells are generated through autologous cell division. The progenitor/stem cells are activated only in situations when massive injury has occurred [23]. The salivary gland is known for its vigorous regeneration capabilities. This capability might be accounted for by its secretion of a plethora of growth factors, particularly epithelial growth factor (EGF), and the presence of multiple types of stem/progenitor cells at different parts of the glandular unit. Epithelial stem cells have also been identified in the stroma on the other side of the basement membrane [24]. The salivary glands are highly innervated and the nerve tissue plays an important role in the organogenesis [24]. The multiple populations of stem cells show neural stem cell intermediate filament (nestin) and neuronal markers such as glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), neurofilament (NF), and protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5).

Overview of Salivary Gland Tumors

Salivary gland tumors include a wide range of morphologically different entities, benign or malignant. The 2005 WHO classification lists 10 benign and 23 malignant epithelial entities [25, 26]. Several unique features of the salivary gland tumors are discussed here to call attention to their differences from the mammary gland tumors which are also legion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree