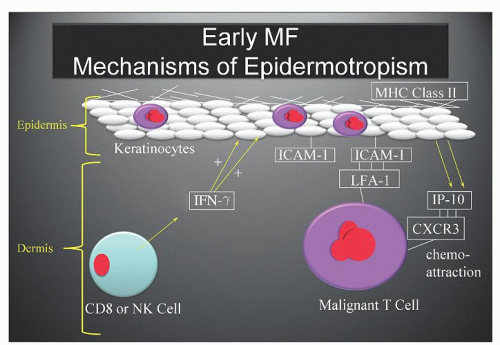

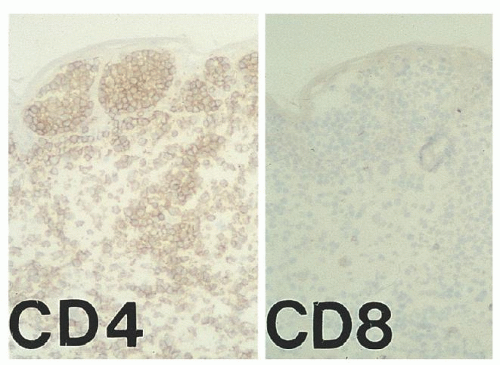

ICAM-1 by keratinocytes is induced by the release of interferon-γ (IFN- γ) from infiltrating CD8+ T-cells or natural killer (NK) cells responding to the malignant T-cell population within the dermis (Fig. 92.2).23 Adhesion molecules other than ICAM-1/LFA-1 have been implicated in the phenomenon of epidermotropism and include E-cadherins, CD58/CD2, B7/CD28, CD49a (VLA-1), CD49c (VLA-3), and CD49f (VLA-6).28 Soluble chemotactic factors may also play a role in the epidermotropism of MF. The expression of the CXC chemokine IP-10 (IFN-γ-inducible protein-10), which is chemotactic for CD4+ lymphocytes, has been shown to be markedly increased by basal and suprabasal keratinocytes in MF lesions.33 Several studies suggest that in early MF, epidermal Langerhans cells convert to hyperstimulatory antigen-presenting cells (CD1a+, CD1b+, CD36+) with a high expression of Class II MHC molecules and adhesion molecules capable of activating tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.23

and 17q gains (isochromosome 17).46, 47, 48, 49, 50 Abnormalities in chromosome 10 have been correlated with progression to tumor stage, including loss of heterozygosity on 10q and microsatellite instability.51 Salgado et al. demonstrated through comparative genomic hybridization oligonucleotide array that in tumor-stage MF, loss of 9p21.3 (encodes CDKN2A and CDKN2B) and 10q26qter, and gain of 8q.24.21 were associated with decreased survival.52 Additionally, p16INK4a, a protein coded at the 9p21 locus, has been shown to be silenced in tumor-stage MF.53 Microsatellite instability was detected in 16 of 56 patients with CTCL that may be a consequence of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation and may prevent transcription in a subset of patients.54 van Doorn and colleagues reported that the malignant T-cells of patients with CTCL display widespread promoter hypermethylation associated with inactivation of several tumor-suppressor genes involved in DNA repair (MGMT, MLH1), cell-cycle (CHFR), and apoptosis signaling pathways.55 Recently, comparative transcriptome analysis was performed on tissue from patients with early-stage MF and benign dermatoses that identified increased expression of the TOX protein in MF. TOX is strongly expressed in thymic tissue but is normally silenced in mature CD4+ T-cells.56 It may prove to be useful as an immunohistochemical diagnostic marker.

cases were estimated to constitute 17% of MF.84 Thus, using the most recent incidence rate, the incidence of new cases of CTCL in the United States in the first decade of the 21st century is almost 3,000 cases per year. The incidence of MF increases with advancing age, and the median age is usually between 60 and 70 years, with an incidence rate of 24.6 per million for persons 70 to 79 years of age and a peak around 80 years of age.82,83 It is rare in patients <30 years of age. However, in the 1990s there emerged several reports of children and adolescents affected with MF and SS.85, 86, 87 One study found that 4% to 5% of patients with MF had onset of their eruption before 20 years of age,87 whereas the more recent epidemiologic study by Criscione and Weinstock showed only 1% of cases of CTCL to be in the <20 years age group.82 A study from the International Childhood Registry of Cutaneous Lymphoma found the mean age of onset and diagnosis of pediatric cutaneous lymphoma to be 7.5 years (±3.8 years) and 9.9 years (±3.4 years), respectively.88

thickening, coalescing plaques, and tumors may result in characteristic “leonine facies” (Fig. 92.4F). The tumor stage is more clinically aggressive than the patch and plaque stages, and may be associated with histologic transformation to a large cell process with a vertical growth phase (see section “Histopathology and Prognosis”).124 Rarely, patients with MF will present initially with tumors without the preceding patch and plaque phases (the MF d’emblée variant).6, 134 It is very common for more advanced patients to have patches, plaques, and/or tumors present simultaneously on different areas of their skin.70

ectropion, nail dystrophy, and ankle edema.136 Intense pruritus and cutaneous pain are common in SS, and when the palms and soles are affected with scaling and fissuring, walking and manual dexterity become difficult.136

TABLE 92.1 WHO-EORTC CLASSIFICATION OF CUTANEOUS LYMPHOMA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

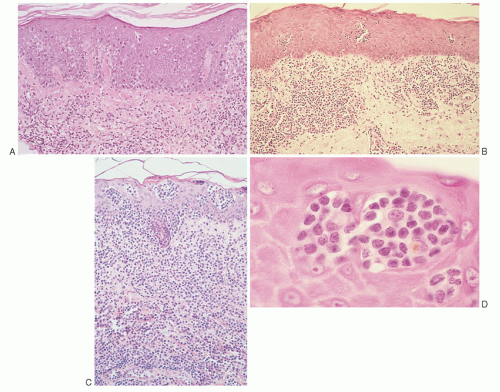

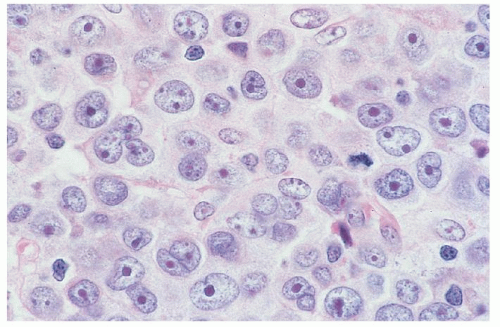

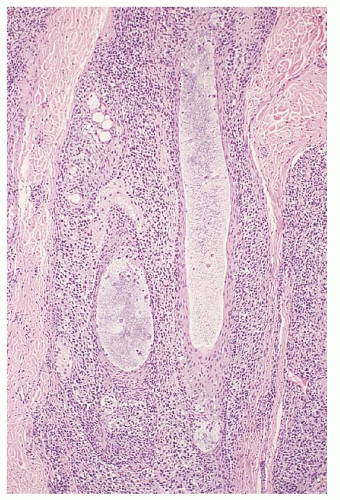

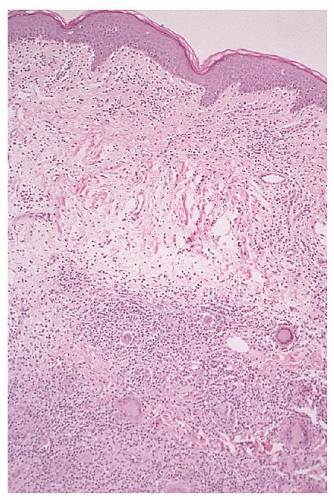

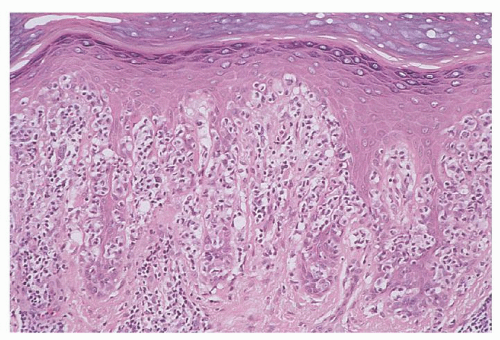

folding requires good fixation (such as B5 fixation), thin (4-µm) sections, and examination under 100× oil immersion. Others have used special methods such as 1-µm sections of plastic-embedded tissue, electron microscopy, or nuclear morphometry.142 Diagnostic criteria for cutaneous involvement by MF are best illustrated in plaque-stage lesions (Fig. 92.5B,C). The essential criteria for diagnosis are (a) a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial papillary dermis, (b) epidermotropism, and (c) atypical cerebriform T-cells in the dermal and epidermal infiltrates.143, 144 Pautrier microabscesses (Fig. 92.5D) are characteristic of MF but are often absent in patch-stage lesions, erythroderma, and nonepidermotropic tumors. Diagnosing early-patch-stage lesions is often difficult. In a morphologic study of >700 early-patch-stage lesions by Massone et al., the histologic features most helpful for diagnosing MF were (a) epidermotropism, particularly with a basilar lymphocytosis (23%) or with “haloed” lymphocytes (40%); (b) a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that is bandlike (30%) or patchy lichenoid (66%); and (c) interface dermatitis (59%).145 Large convoluted lymphocytes in the epidermis were found only in 9% of cases, and Pautrier microabscesses were found in 19%. The authors noted that although these cytologic changes are highly specific, the architectural abnormalities (infiltrate, epidermotropism) were more sensitive in diagnosing MF, as has also been suggested by others.146 Earlier studies have shown similar criteria as being valuable in diagnosing MF “haloed” epidermotropic cerebriform T-cells along the basal layer of the epidermis, disproportionate epidermotropism (intraepidermal lymphocytes without accompanying spongiosis), and medium to large cerebriform cells in the epidermis and clustered in the dermis.143, 147, 148 Several studies have pointed to the association of papillary dermal fibrosis with MF/SS; however, at least one study found that in a carefully selected population of early, untreated MF patients this finding argued against a lymphoma diagnosis.149

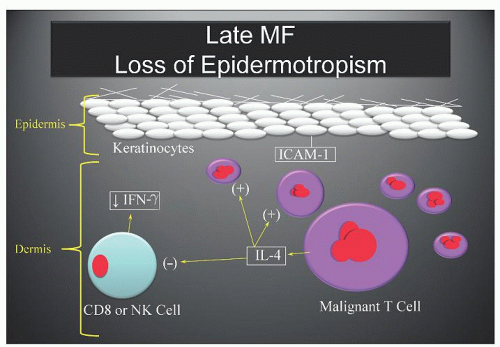

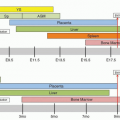

nodes, liver, spleen, and lungs, which may be involved in >50% of more advanced cases.172 Other common sites include kidney, bone marrow, thyroid, heart, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. Lymph nodes represent the most frequent site of extracutaneous disease in pathologic staging studies; up to 50% of lymph nodes are positive by light microscopy at initial staging.173 Several series from the 1980s found visceral involvement present in ˜15% of initial staging liver and bone marrow biopsies.157, 173, 174 When staging laparotomies were routinely performed in the past, ˜30% of spleens were microscopically involved by MF/SS.175 Extracutaneous CTCL, particularly visceral disease, is strongly associated with advanced-stage skin disease (tumors and erythroderma) and SS.174 Because tumor-stage MF and generalized erythroderma are frequently nonepidermotropic, it has been suggested that loss of epidermotropism may play an important role in systemic dissemination.

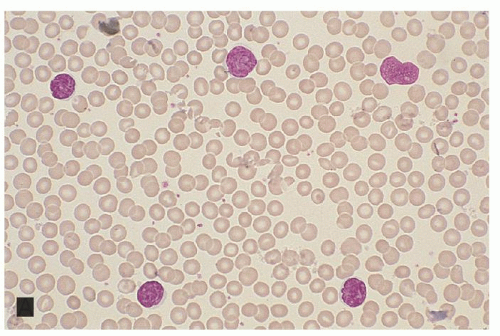

molecularly negative (B0a) cases even when the histologic criteria for blood involvement have not been met.162, 187, 188 In fact, T-cell clonality in the peripheral blood even in the absence of increased lymphocytes by morphology or flow cytometry (B0b) has been shown to convey a worse overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival and risk of disease progression.189 B1 stage is defined as the group of patients who fail to meet criteria for B2 or B1. These patients have >5% atypical T-cells but do not otherwise reach the criteria for B2 involvement. These patients can also be split into B1a molecular clone negative and B1b molecular clone positive cases. Although T-cell clonality is required for diagnosis of B2 stage, the presence of molecularly defined T-cell clones in elderly patients or in patients with other lymphoproliferative disorders is not uncommon151, 190, 191 requiring therefore correlation with the clonality of the cutaneous infiltrate or association with MF-associated immunophenotypic abnormalities (increased CD4:CD8 ratio, loss of CD7 or CD26 on CD4 T cells).

disease psoriasis. Most dermatologists separate parapsoriasis into one of two types. The benign subtype is known as small plaque parapsoriasis, digitate dermatosis, or chronic superficial dermatitis. The other type is considered pre-malignant and is most often called LPP or parapsoriasis en plaques (having in the past been called pre-reticulotic poikiloderma).206, 207 LPP is clinically indistinguishable from patch-stage MF.126 However, the patches of MF tend to be fixed whereas the patches of LPP tend to wane in the summer and flare in the winter. Because of clinical and histologic overlap, some authorities consider LPP to be an early stage of MF.208 Others consider LPP to be a latent form of MF209 because ˜10% of patients eventually develop overt MF.210 A retrospective review documented a higher rate of evolution to MF in 12 of 36 (33%) patients with LPP.211 This view is supported by the demonstration of clonal TCR gene rearrangement in 50% of LPP biopsies.73 Furthermore, demonstration of clonal TCR gene rearrangements in small plaque or digitate parapsoriasis has suggested that this may be an abortive form of MF.212, 213 Histologically, the lymphoid infiltrate of LPP is perivascular and less dense with less epidermotropism than in MF; Pautrier microabscesses are not seen in LPP. Furthermore, cytologically atypical cerebriform T-cells with highly convoluted nuclei are inconspicuous or absent in LPP. However, immunophenotypic analysis is usually not helpful for differentiating LPP from patch-stage MF as both have a predominance of CD4+ helper cells with absent CD7 and CD62L expression.127 One study found the presence of HECA-452 immunostaining higher in MF than LPP, which may be helpful in distinguishing the two diseases and predicting which cases of LPP may evolve into MF.214

TABLE 92.2 BENIGN AND MALIGNANT CONDITIONS THAT CAN MIMIC MF AND SÉZARY SYNDROME | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

the polyclonal and monoclonal groups.228 Other studies have documented the frequent occurrence of T-cell clonality in cases of PPD that fail to develop disease typical of MF.229 The presence of extensive PPD-like skin disease, especially when present outside the lower extremities, should raise the suspicion of MF regardless of the histologic features.

B LyP typically do not express CD30.256 Vonderheid and Kadin have suggested that the papular variant of MF and type B LyP are the same entity256 although Kodama and colleagues point to the lack of spontaneous resolution of papules in papular MF.257 Clinical behavior of LyP is usually benign; however, overt lymphoma has been documented in ˜10% to 25% of patients, usually MF, pcALCL, or Hodgkin lymphoma.248, 258 The cumulative risk for the development of another lymphoma in patients with LyP over 15 years of disease may be as high as 80%.259 A retrospective review of 31 patients with LyP over a 27-year span identified 60% who developed a co-existing lymphoma.258 No clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, or molecular genetic features have been identified that can predict which patients will develop lymphoma, but two studies suggest that malignant transformation is more strongly associated with type A than with type B LyP.256 Onset of LyP at a younger age may be associated with increased cumulative risk for overt lymphoma and therefore all LyP patients should be closely monitored throughout their lives.221, 259, 260 The benign or malignant nature of LyP is controversial, but the WHO-EORTC considers LyP to be a latent or low-grade stage of the primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders that are considered to be malignancies.137, 261 Its clinical, histologic, and immunophenotypic similarities to pcALCL, aberrant T-cell-antigen expression, clonal TCR gene rearrangements, and increased risk for transformation to malignant lymphoma support this view.

as CGDTCL according to the WHO-EORTC guidelines. Clonal TCR gene rearrangement and aberrant T-cell-antigen expression support classification of PR as a form of CTCL;279 however, PR has a clinically benign course, with only rare reports of cutaneous dissemination of localized PR.276 Further studies are needed to confirm whether phenotypic differences in PR have clinical relevance. Local excision or radiation therapy is generally adequate treatment for PR, especially the localized form.

FIGURE 92.10. Pagetoid reticulosis. Note the pronounced pagetoid pattern of epidermotropism by enlarged, atypical cerebriform T-cells (hematoxylin and eosin, ×50). |

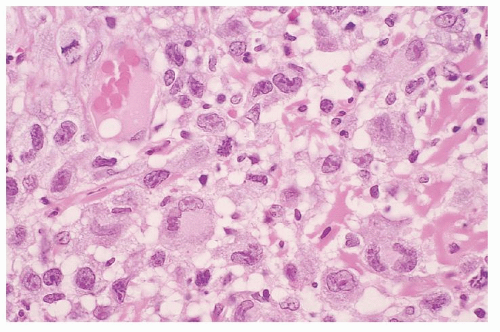

extend to the dermis or epidermis.304, 305 Classically, T-cells ranging from small and inconspicuous to large and transformed cells with hyperchromatic nuclei rim individual fat cells.306, 307 There is necrosis, karyorrhexis, and cytophagocytosis by the histiocytes that are found interspersed in the lesional tissue. As the name implies, this lymphoma is similar in histology to a lobular panniculitis and, in fact, many patients present with a history of previously biopsied panniculitis. In addition, there is some clinical and histologic overlap with lupus panniculitis and many patients with SPTL will present with or develop evidence of concomitant systemic lupus erythematosus.308, 309, 310 By immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic T-cells express αβ TCR, CD3, CD8, and cytotoxic granule proteins, although CD56 and CD30 are rarely detected.304, 306, 307, 311, 312 Historically SPTL had been associated with a very poor prognosis often secondary to an aggressive hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS). The more recent WHO-EORTC classifications divided these cases into SPTL with an αβ phenotype and CGDTCL based both on immunohistologic features and clinical behavior. SPTL with an αβ phenotype are CD4–, CD8+, CD56–, and βF1+; are limited to the subcutaneous fat; are uncommonly associated with a HPS; and have a favorable prognosis (5-year OS 82%). CGDTCL is generally CD4–, CD8–, CD56+/-, and βF1–; tends to involve the epidermis with resulting ulceration; is commonly associated with HPS; and has a dire prognosis (5-year OS 11%).313 Repeat biopsies may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis of SPTL. Once confirmed, early induction of combination chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy may yield remission and prevent the development of HPS.314, 315, 316 (For further discussion of SPTL, see Chapter 88.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree