Chapter 38 Cryptosporidia, Isospora, and Cyclospora Infections

It has only been since the recognition of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic that the spore-forming protozoa that infect the gastrointestinal tract (Cryptosporidium, Microsporidium, Isospora, and Cyclospora) have been identified as significant, ubiquitous human pathogens. Initially, these pathogens were thought to cause only rare or esoteric infections; but it is now recognized that they infect both immunocompetent and immunodeficient hosts worldwide.1–3 In many communities, infection with these parasites is the leading cause of chronic diarrheal illness. In the developing world, where more than 90% of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients live, diarrheal illness usually due to these protozoa is the most common opportunistic infection after tuberculosis.

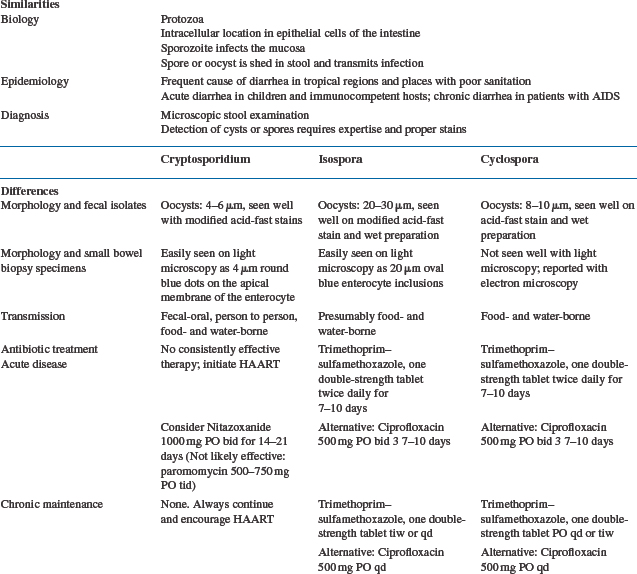

The spectrum of illness caused by these enigmatic parasites is broad and is closely linked to host immunocompetence.4 This explains why infections by these pathogens were first recognized in severely immunocompromised individuals with AIDS who presented with chronic diarrhea and wasting illness. Clearance of these intestinal pathogens is directly related to the ability to mount an effective immune response at the site of the infection, the intestinal mucosa. For example, among patients with cryptosporidiosis, the course of disease is directly related to the stage of immunodeficiency as measured by the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.4,5 What has become clear, with the widespread use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), is that the best therapy for some of these pathogens, such as that causing cryptosporidiosis, is augmentation of immune responses through direct suppression of HIV replication with antiretroviral agents.6–9 The severity of illness with the two most common of these protozoal parasites, Cryptosporidium and Microsporidium, appears to be linked to improvement or deterioration of immune function related to suppression or activation of HIV. We have come full circle in that the HIV epidemic has uncovered many of the biologic, epidemiologic, and immunologic secrets of these protozoan infections among humans; and now better therapy for HIV is leading directly to curative treatment for patients with these protozoal parasites through immune restoration. This chapter deals with Cryptosporidium, Isospora, and Cyclospora. Microsporidium is addressed in Chapter 39. Table 38-1 highlights many of the similarities and differences among these three parasites.

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM

Clinical Presentation

Typically, acute infection with Cryptosporidium is characterized by watery diarrhea, crampy epigastric abdominal pain, weight loss, anorexia, malaise, and flatulence.3,5 Diarrhea, the most noteworthy symptom, can range from a few loose bowel movements a day to more than 50 stools (more than 15 L) per day. Nausea and vomiting are common. Diarrhea and abdominal pain are usually exacerbated by eating, particularly with difficult-to-digest foods such as milk and dairy products or fatty foods. The spectrum of symptoms from infection varies widely; in fact, there are reports of asymptomatic shedding of Cryptosporidium for months after the primary infection.

Cryptosporidial enteritis occurs in HIV-infected individuals who are immunologically competent, as determined by a normal CD4+ T-lymphocyte count. Those individuals have a clinical course similar to HIV-seronegative persons; they are able to clear the infection over a few days to a few weeks.4,5 The median CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of individuals who develop chronic severe disease is well under 50 cells/mm3,5 whereas it appears that patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts higher than 200 cells/mm3 are able to clear cryptosporidial enteritis.4

A subset of patients with AIDS and cryptosporidiosis develop biliary tract involvement associated with right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting.5,10 Laboratory examination is significant for elevated serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transferase levels. This is a difficult-to-treat complication in individuals with exceedingly low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and long-standing chronic cryptosporidial enteritis.5,11 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may reveal dilatation of bile ducts with multiple luminal irregularities and distal duct strictures consistent with partial obstruction or sclerosing cholangitis.

Physical examination of individuals with cryptosporidial enteritis is usually unrevealing. Patients may have orthostatic hypotension and other signs of dehydration. Low-grade fever and mild leukocytosis are common. The abdomen is soft, with mild tenderness to palpation. Laboratory examination often reveals electrolyte disturbances consistent with diarrhea and dehydration. Fecal examination may reveal mucus, but blood and leukocytes are rarely seen. Charcot–Leyden crystals are characteristic of Isospora belli infection and amebiasis but not cryptosporidiosis.2 Lactose intolerance and fat malabsorption are well documented, and the D-xylose test is abnormal. An abnormal D-xylose test correlates strongly with small intestinal infection with Cryptosporidium and Microsporidium.12,13

Biology

Cryptosporidium, Isospora belli, and Cyclospora are spore-forming sporozoa in the class of human protozoal pathogens.1,3 Sporozoites are seen within oocysts and are the infectious form of the parasite.14 Cryptosporidium infection has been identified in numerous species of animals, including mammals, fish, turkeys, and even reptiles such as rattlesnakes.1

Although the parasite was first described in 1907,15 it received no clinical attention until it was recognized as a significant cause of diarrhea in domestic animals (e.g., cows, horses, pigs). The first human case was described in 1976,16 but cryptosporidiosis was thought to be an esoteric illness until 1982, when the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported 21 homosexual men with severe diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium.17 It is now recognized that Cryptosporidium is the number one cause of protozoal diarrhea worldwide in both immunocompetent and immunodeficient persons.

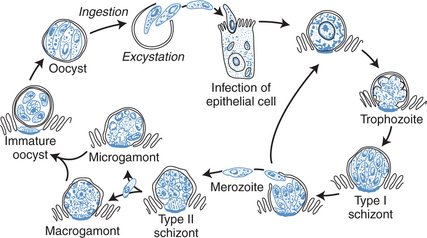

Intestinal infection is initiated by ingestion of the oocysts, with subsequent excystation and release of four sporozoites from each oocyst in the gastrointestinal tract. Sporozoites implant immediately in the host epithelial cells and begin a cycle of autoinfection at the luminal surface of the epithelium. The sexual stage of the parasite results in oocysts, which are excreted in the stool and are immediately infectious to other hosts and can reinfect the same host, even without reingestion. Figure 38-1 shows the life cycle of Cryptosporidium. An infectious dose of Cryptosporidium is as low as 10 oocysts, thereby facilitating transmission.18

Figure 38-1 Life cycle of Cryptosporidium species.

From Flanigan TP, Soave R. Cryptosporidiosis. Prog Clin Parasitol 3:1, 1993.

The most common site of Cryptosporidium infection is the small intestine, although it is frequently present in the colon and the biliary tract of persons with immunodeficiency.2,12,13 Cryptosporidium infects only the epithelial surface of the mucosa; it does not invade the submucosal layer or cause ulcerations. Infection of the epithelial lining of the respiratory tract with associated cough has been reported, although it is uncommon.1

Cryptosporidium is a ubiquitous parasite; and transmission has been documented from animals to humans, from humans to humans (particularly in day-care centers), and from environmental sources such as water reservoirs.1,19,20 Person-to-person transmission of Cryptosporidium is often underappreciated; outbreaks have been well documented in the hospital setting and in families. In Michigan, for example, 71% of families with a symptomatic child had other infected family members.21,22 All individuals in the hospital setting with crypt-osporidial diarrhea should follow enteric precautions, although isolation is not necessary to prevent roommate-to-roommate transmission.23

Cryptosporidium has been identified as the etiologic agent of several extensive water-borne outbreaks usually caused bysurface-infected groundwater sources, often involving farm animals.11 The oocyst is only 4 mm in diameter, making it difficult to clear through filtration, and it is resistant to routine chlorination.19 The first documented water-borne outbreak (in San Antonio, Texas) had a 34% attack rate and was linked to sewage contamination of the well water supply, which was chlorinated but not filtered.24 In 1987 an outbreak in Georgia resulted in an estimated 13 000 cases of cryptosporidial enteritis despite the filtered and chlorinated public supply that met the established Environmental Protection Agency guidelines.20 Improved filtering of the water supply ultimately helped terminate the outbreak. An outbreak in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1993 afflicted some 375 000 residents when the spring runoff from grazing lands was not adequately filtered in the public water supply.11,25 This massive environmental contamination led to severe illness with both small intestinal disease and biliary tract infection in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts under 50 cells/mm3, and it resulted in a marked increase in morbidity and mortality in these patients.11

The recognition of Cryptosporidum as a pathogen of concern in HIV-infected patients in the resource-limited world has led to additional observations about the clinical presentation of cryptosporidial disease. Early in the HIV epidemic, cryptosporidial diarrheal illness was considered a severe and relatively untreatable disease due to an opportunisitic pathogen. The disease is more severe in those individuals in whom immune compromise was more advanced. Recently, with advances in diagnostic techniques and better surveillance, the asymptomatic carriage of cryptosporidial organisms has been recognized in a variety of settings.26–28 In the setting of asymptomatic carriage of cryptosporidium in the noncompromised host, there are suggestive data that this carriage may compromise nutritional status in children, even in the absence of diarrheal illness.29 Recent studies have also suggested that HIV-infected patients with severe immune compromise may carry cryptosporidial organisms asymptomatically.30,31 The extent and impact of asymptomatic carriage of cryptosporidial organisms and the species and genotype of organisms carried asymptomatically in HIV-infected patients requires further study.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Cryptosporidium is primarily based on identifying the oocysts in stool.32 Oocysts stain red with varying intensities with a modified acid-fast technique; this technique allows differentiation of the Cryptosporidium oocysts from yeasts that are similar in size and shape but not acid-fast. Oocysts can also be detected by direct immunofluorescence assays that are commercially available utilizing monoclonal antibodies raised to Cryptosporidium antigens.33 In addition, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay may be used to detect Cryptosporidium in fecal specimens and tissues.34,35 There is no consensus on the optimal oocyst detection method in fecal samples, although one comparison of a modified acid-fast stain and a fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibody technique showed comparability for diarrheal samples but improved detection with the immunofluorescence method for formed specimens.26,36 Cryptosporidial enteritis can also be diagnosed on small intestinal biopsy sections by identifying developmental stages, found individually or in clusters, on the brush border of the mucosal epithelial surfaces.36 Organisms project into the lumen because of their intracellular but extracytoplasmic nature, and they appear basophilic with hematoxylin and eosin staining. Electron microscopy allows resolution of cellular detail.

While not generally available clinically at present, a number of genetic loci have been identified as targets for detection of cryptosporodial isolates as well as genotype determination. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods are exquisitely sensitive for detection of organisms, either from stool samples or environmental samples. These methods may detect as few as 1–10 oocysts or as many as 80 oocysts in a gram of stool. Thus while these methods are sensitive and specific, and may ultimately be used to more readily screen large numbers of samples for presence and genotype of the cryptosporidial organisms present, there are technical issues which preclude their routine clinical use. These technical issues should be resolved and PCR based diagnostics will likely be used in clinical practice in the near future.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree