Correlation of Endoscopy with Histopathology in Gastric Neoplasm

Michio Shimizu

Hiroto Kita

Koji Nagata

INTRODUCTION

Conventional (white light) endoscopy and endoscopically directed biopsies of the upper gastrointestinal tract are routinely performed in gastroenterology units. In practice, the biopsy sampling is obtained on the basis of gross morphological changes, so that the pathological diagnosis is directed by the endoscopic findings. Generally speaking, gastric lesions are endoscopically divided into two broad types: elevated and depressed. The differential diagnosis of elevated lesions is broad and includes polyps (fundic gland and hyperplastic), polypoid dysplasia (i.e., adenoma), adenocarcinoma, and protruding submucosal tumor (e.g., carcinoid). Depressed lesions encompass benign erosion, ulcer, and scar (from previous ulceration) and malignant processes (e.g., adenocarcinoma and malignant lymphoma).

The endoscopic appearance of early gastric cancer is variable: poorly differentiated type adenocarcinoma (the so-called undifferentiated type) tends to present as a depressed lesion, but the well to moderately differentiated type (the so-called differentiated-type adenocarcinoma) can present as either a protruding lesion or a depressed lesion.1,2 Further evaluation of the lesions includes assessment of shape, color, contour, margin, and size, all characteristics that help define the diagnosis. However, conventional endoscopy is limited by the detection of lesions on the basis of gross findings under direct vision; for example, the margin of depressed lesions is sometimes difficult to identify. Instead, chromoendoscopy, that is, the use of stains or dyes such as indigo carmine, improves the visualization and characterization of lesions.3,4 In particular, it highlights and improves identification of 0-II type (depressed type) lesions that may not be otherwise discernible.5, 6 and 7 However, Western endoscopists rarely appreciate the routine use of chromoendoscopy.

Magnification endoscopy (or “magnifying endoscopy”) and NBI play an especially important role in the diagnosis of gastric lesions.8, 9 and 10 These methods in particular allow precise evaluation of the microsurface structure and microvascular architecture of the mucosa that are closely related to pathological findings. Therefore, understanding the pathological findings becomes even more important for endoscopic diagnosis of gastric lesions.

Recent technical progress has expanded the use of endoscopy as not only a diagnosis modality but also a therapeutic modality. EMR and ESD are now performed as alternatives to surgery for the treatment of both premalignant lesions and carcinomas limited to the mucosa.11,12 This chapter focuses on these new endoscopic techniques and the correlation

between endoscopic and pathologic findings in commonly diagnosed gastric neoplasms. The readers are referred to each individual chapter for in-depth pathologic review of the various entities covered herein.

between endoscopic and pathologic findings in commonly diagnosed gastric neoplasms. The readers are referred to each individual chapter for in-depth pathologic review of the various entities covered herein.

NEW ENDOSCOPIC TECHNIQUES

Magnification Endoscopy and Narrow-Band Imaging

Magnification endoscopy is very useful for detecting subtle mucosal lesions, including early stage gastric neoplasm. Practically, however, the best strategy is first to perform conventional endoscopy to detect any mucosal lesion. When an abnormality is found, visualization of the lesion is zoomed up to maximal magnification. Magnification endoscopy will enable the determination of whether the lesion is neoplastic, and its extent.

The findings of magnification endoscopy are based mainly on the evolution of microsurface structure and microvascular architecture. By white light alone, only the microvascular architecture can be identified, but with NBI, both the microsurface and microvascular architectures can be observed. NBI takes advantage of an intrinsic contrast agent, hemoglobin, to highlight the superficial microvascular anatomy. In recently developed endoscopes, it is easy to change the level of structure enhancement, and the light source can be changed from white light imaging to NBI by using switches on the scope.13,14

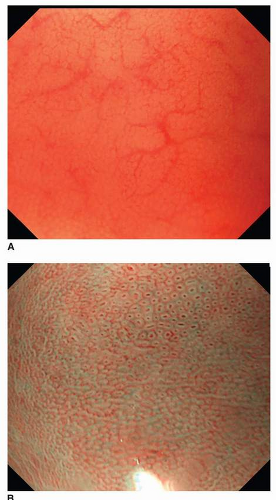

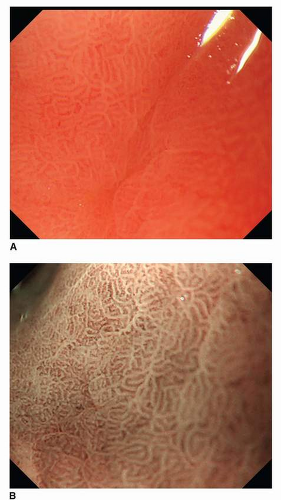

Magnification endoscopic findings in the normal stomach differ by location. The body mucosa reveals a honeycomb-like subepithelial capillary network pattern with collecting venules, while normal antral mucosa demonstrates a coil-shaped subepithelial capillary network pattern without any collecting venules. The microsurface structure also is variable; the openings of crypts in the body mucosa are round or oval, whereas the openings of crypts in the antrum display a linear or reticular pattern (Figs. 11-1 and 11-2).15,16 Magnification endoscopy can identify Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. A regular pattern of collecting venules indicates the absence of H. pylori infection.17, 18, 19 and 20 Using NBI, a fine, bluish-white line that appears on the crests of the epithelial surface/gyri is a good indicator of intestinal metaplasia.20 The patterns of various neoplasms under magnification endoscopy with NBI are described separately below.

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection and Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

Pioneered in Japan for treatment of superficial gastric cancers, EMR is now widely used in the West for treatment of Barrett esophagus-related neoplasms as well as uncommon early gastric neoplasms.21,22 EMR is one of the most recommended procedures for therapy of early gastric cancer because it is noninvasive. In addition, in contrast to other endoluminal techniques (laser, plasma coagulation), EMR does not destroy the epithelium and thus allows collection of the complete specimen for pathological evaluation.23,24 In EMR, however, mucosa sampling cut using a snare poses a high risk of piecemeal resection for lesions measuring 10 mm or more.25

ESD is a more recent technique that uses electrosurgical knives instead of a snare, extending the plane of resection in the deep submucosa. ESD provides more accurate resections of superficial neoplasms than EMR. It is a reliable technique for an en bloc resection regardless of the size and location of the lesion. It is also more effective therapeutically.25

Whether specimens are obtained through EMR or ESD, the handling is very important for providing optimal pathologic diagnosis. The histological type, the presence or absence of lymphatic and vascular invasion, the depth of invasion, and the status of vertical and lateral margins should be reported precisely.26 If complete resection is not obtained, additional endoscopic resection or surgical treatment will be needed. The precise procedure of EMR and ESD has been described elsewhere.25

ENDOSCOPIC AND PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS IN REPRESENTATIVE GASTRIC NEOPLASMS

Adenoma

Adenomas account for 7% to 10% of all gastric polyps in most large series.27 Most are sessile, and pure pedunculated lesions are rare. Under endoscopy, adenoma and carcinoma can produce 0-IIa type gastric lesion (superficial elevated or slightly elevated type).9 However, a white opaque substance (WOS) noted during magnification endoscopy with NBI is detected more frequently in adenomas than in carcinoma (Fig. 11-3).9 In addition, WOS shows a regular distribution (regular WOS) in adenomas, while it tends to be irregularly distributed (irregular WOS) in carcinomas.

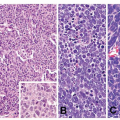

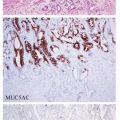

Microscopically, two phenotypes are recognized: intestinal type and gastric type.27 Intestinal type adenomas resemble colorectal adenoma. They are composed of mostly tubular structures that typically reveal a double-layered structure in which the basal half of the mucosa contains cystic tubules (Fig. 11-4). They are characterized by the presence of goblet cells and Paneth cells. Adenomas are considered to be benign; however, malignant transformation occurs in about 2% of lesions measuring under 2 cm, and approximately 50% of lesions larger than 2 cm.28 Gastric type or foveolar dysplasia is characterized by cuboidal to columnar cells with pale, clear to light eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei. Architecturally, the glands tend to be smaller than in adenomatous dysplasia.

Early Carcinoma

Early gastric cancer is defined as any carcinoma confined to the mucosa (intramucosal carcinoma) and the submucosa, regardless of the presence of lymph node metastasis. Superficial gastric cancers

are curable, with a 5-year survival rate surpassing 90%.29

are curable, with a 5-year survival rate surpassing 90%.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree