Correction of Partial Breast Deformities with the Lipomodeling Technique: Introduction

Moderate sequelae of conservative treatment of breast cancer are a real challenge for the surgeon.1 No technique yet gave entirely satisfactory results. The only options offered to patients, such as musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flaps,2,3 were often disabling and disproportionate to the breast deformity.1 But a few years after treatment of their cancer, patients are very eager for surgical correction of their deformity to erase or attenuate the visible signs of their disease. It was therefore important to seek a solution that would correct these sequelae and help these patients to regain better self-esteem and to reintegrate their breast in their body image.

We had obtained very good results with fat transfer in the face, and so in 1998 we proposed fat transfer for breast improvement after reconstruction. We first introduced this approach after autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction.4,5 Finding that fat transfer was effective and innocuous, we proposed using it to correct therapeutic sequelae of the breast. We carried out a radiological study on reconstructed breasts that had undergone lipomodeling, and this showed no deleterious effects on breast imaging.6

This chapter presents the information that should be given to the patients and the precautions that should be taken before carrying out this procedure, the surgical technique, the results that may be expected, the advantages and drawbacks of the technique, the potential radiological appearance after lipomodeling, and lastly the possible medicolegal aspects if local recurrence of cancer occurs coincidentally with lipomodeling.

The use of fat transfer in breast surgery is not a new concept.7 More recently, and from the early days of modern liposuction, Illouz8 and Fournier9 suggested using the fat obtained from liposuction for moderate breast augmentations. Bircoll10 presented a similar approach and drew attention to the advantages of this technique in a paper published in February 1987 in the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery10: simplicity, absence of residual scarring, early return to normal activity, elimination of the need for implants and also their complications, with an additional secondary advantage in the areas of fat harvesting. Then in April 1987 he published11 a report of a patient who had undergone bilateral fat transfer after unilateral reconstruction with a transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap (improvement of the reconstructed breast and restoration of symmetry). These 2 papers at once prompted considerable extremely virulent opposition.12-16 His detractors underlined the fact that fat injections in a native breast could produce microcalcifications and cysts, making a cancer difficult to detect. Although Bircoll stressed in his replies17,18 that the calcifications after fat transfer differ from neoplastic calcifications by their location and their radiological appearance, and that breast reduction surgery also generates microcalcifications, the debate started unfavorably, and in 1987, the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons (ASPRS) ruled as follows: “The committee is unanimous in deploring the use of autologous fat injection in breast augmentation. Much of the injected fat will not survive, and the known physiological response to necrosis of this tissue is scarring and calcification. As a result, detection of early breast carcinoma through xerography and mammography will become difficult and the presence of disease may go undiscovered.” These affirmations were made without any previous scientific studies and were based on the opinion of the committee members of the ASPRS. Since then, in spite of the lack of more extensive references, and although it was recognized at the time that any breast surgery could potentially generate oily cysts and/or mammographic changes, injection of fat in the breasts had become a powerful taboo that no one officially attempted to breach. Ironically, in 1987, a retrospective study of mammographic changes after breast reduction19 published in the same journal reported that calcifications were found in 50% of cases at 2 years, and the authors stressed that in the majority it was possible to differentiate them from cancerous changes. In spite of this very high incidence and once again the risk of interference with detection of a breast cancer, of course no discussion took place on abandoning breast reductions.

In 1998, the aims of our research on fat transfer in the breast were to improve the technique so as to reduce fat necrosis and to attack the powerful taboo that for some 10 years had halted research, evaluation, and publications on this topic. In fact, because we had observed that fat transfer was extremely effective in the face, in aesthetic surgery, and in treatment of facial sequelae after injury or cancer treatments (a technique that we used notably after the publications of Coleman20,21), we thought of applying this technique to breast reconstruction, and we decided it should be one of our areas of research. First of all, we applied fat transfers to breast reconstructions with an autologous latissimus dorsi flap.22 This technique of autologous breast reconstruction had in fact been developed in our unit of plastic and reconstructive surgery.22 It restored satisfactory breast volume in 70% of cases, but in 30% the volume was insufficient and either the opposite breast had to be reduced or an implant had to be used. This meant that the procedure was no longer purely autologous, and it was accompanied by the drawbacks of implants (less natural shape and consistency, need for implant replacement). So we then started to use fat transfers in breasts reconstructed with autologous latissimus dorsi flaps, where the risk of local recurrence was considered very low. The protocol was initially offered to voluntary patients who agreed to undergo strict surveillance. Then, as we found that this technique was extremely effective and that tolerance was excellent, we extended its indications to most patients who had breast reconstruction with autologous latissimus dorsi flaps and who wished for optimal shape and consistency and as natural a décolleté as possible. In parallel, we carried out a mammographic, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study6 that showed that the effect on breast imaging was far from unacceptable. We then progressively extended the indications of lipomodeling to the various situations of breast reconstruction, then to breast and thoracic deformities, to sequelae of conservative treatment, and more recently to cosmetic breast surgery. The first presentations to the Société Française de Chirurgie Plastique et Reconstructrice23 and the International Confederation24 gave rise to sometimes acid comments, reviving the antagonisms of 1987. These were countered point by point. Then as the presentations continued, the opposition of the scientific community lessened as one congress followed another, and fat transfers are now accepted as part of the therapeutic armamentarium for breast reconstruction. Our efforts toward systematic scientific evaluation led to the request that our team write the chapter on the subject in the American reference work on plastic surgery of the breast.4

During the preoperative visit, the patient’s details and the history of her disease are recorded and her expectations are assessed. Each patient is given precise, detailed information both orally and in written form (a specific information sheet) that comprehensively explains the modalities of the procedure, its advantages, drawbacks, and possible complications. We particularly emphasize that fat loss is normal during the early months, that the procedure may possibly have to be repeated if the patient has major sequelae, and that the result may alter if she gains or loses weight. Patients are also informed of the postoperative bruising, which can be impressive at the donor site, and of residual scarring, even if this is minimal.

During meticulous clinical examination, the conserved breast is compared with the opposite breast, and the areas that require correction are identified and marked with the patient standing. The symmetry of the breasts is assessed, their overall volume and fullness, the position of the nipple-areola complex, the severity of loss of substance and volume, and depressed or retractile scars if any. The quantity of fat to be harvested and transferred is also assessed, as well as the need for any complementary measures such as restoration of symmetry, tattooing, and/or a nipple graft. The adipose areas where the fat will be harvested are identified. Abdominal fat is most often used because harvesting in this area does not require a change in the patient’s position during the procedure. The second site is the trochanteric region (saddlebags), often combined with harvesting from the inside of the knees and the back of the thighs. It is important that the patient’s weight be stable at the time of the procedure because the transferred fat retains the memory of its origins, and if the patient loses weight after lipomodeling, she will lose some of the benefit of the procedure.

As part of the protocol, all patients undergo full imaging, including mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, before as well as 1 year after the procedure. The risk of local recurrence is clearly explained to the patient, as well as the risk that a cancer may occur coincidentally with lipomodeling. It is also explained that in the event of recurrence, mastectomy with immediate reconstruction will be performed.25

The lipomodeling technique used in the sequelae of conservative treatment is derived from that used in breast reconstruction.2,3 It aims to transfer fat from an area with excess adipose tissue to the conserved breast that presents a deformity or is lacking in volume. The procedure is carried out in the surgical suite under general anesthesia. Conventional prophylactic antibiotics are usually given perioperatively.

The patient is installed and draped so that she can be moved from a supine to a semisitting position if fat is harvested from abdominal and suprailiac deposits. If fat is harvested from the trochanteric or subgluteal area or the inside of the thighs, the patient is placed in a prone position and then turned over and entirely redraped for the reinjection.

Fat is harvested with a blunt 3-mm cannula (Fig. 78-1A) after preliminary infiltration of serum with adrenaline.

The incisions are made according to the harvesting area, with a No. 15 blade. Abdominal fat is harvested through 4 cardinal incisions around the navel. In the flanks, a suprailiac incision is made on each side. For the gluteal and trochanteric regions, the incisions lie in the subgluteal folds. We use 10-mL Luer Lock syringes.

With the finger, the operator makes a moderate, gradual depression that creates a differential of a few cubic centimeters between the aspirated fat and the piston to minimize damage to the adipocytes (Fig. 78-1A).

Both deep and superficial fat are harvested. At the end of the procedure, the harvesting site is often recontoured by liposuction for a better cosmetic result. When harvesting is completed, the same cannula is used to inject 7.5 mg Naropin (ropivacaine hydrochloride) with an equal volume of normal saline to alleviate postoperative pain during the first 24 hours.

The incisions are closed by separate stitches using rapidly absorbed suture material (Vicryl Rapide 3–0).

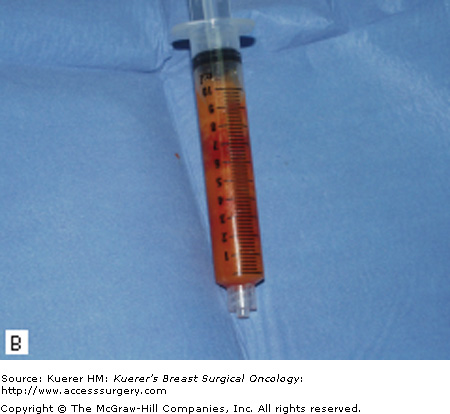

As harvesting continues, the instrument nurse prepares the syringes for centrifugation. They are sealed with a plastic cap, the piston is withdrawn, and they are placed in the centrifuge in batches of 6 for 3 minutes at 3000 revolutions per minute. After purification, the fat separates into 3 layers (Figs. 78-1B, C):

- A top layer of oil resulting from cell lysis (chylomicrons and triglycerides)

- A bottom layer of blood residues

- A middle layer of purified adipocytes (this is the valuable part that will be used for transfer)

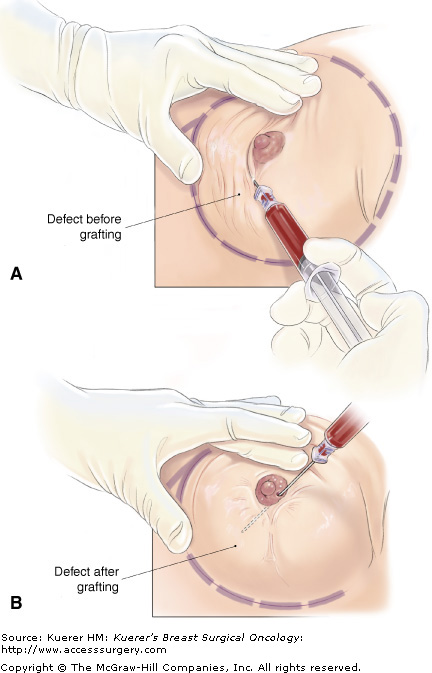

After preparation of the fat, several punctate incisions are made with the bevel of a pink trocar to create a cross-work of tunnels for the transfer of fatty tissue. The fat is then reimplanted in its new site using special disposable fine 1.5-mm cannulas (Fig. 78-1D). Deep tunnels must be made in all planes, from the ribs to the skin, following the preoperative markings and forming a 3-dimensional honeycomb. The fat must be reinjected while the cannula is withdrawn. Care must be taken to avoid using too much pressure (Fig. 78-2), and the fat should be injected in small quantities as if it were spaghetti (Fig. 78-3). This is because of the risk that necrotic cysts will form if too great a volume of fat is injected (centripetal revascularization does not allow survival of large-sized fragments, which become the site of central necrosis with liquefaction and cyst formation).

If possible, volume should be overcorrected. As about 30% of fat is reabsorbed, 140% of the desired volume should be transferred. But very often after conservative treatment, overcorrection is not possible because the tissue receiving the fat is fibrotic. It is advisable not to attempt to continue but to program a second session. During the second session, because of the antifibrotic effect of the fat, larger quantities can often be transferred. At the end of the procedure, the lipomodeled area is covered with a dry dressing, taking care to avoid compression. A compressive Elastoplast dressing is applied to the harvesting sites.

The patient leaves the unit on the same day or the day after the procedure, with class 1 analgesics. The dry dressing on the breast is changed every 72 hours by a private nurse or by the patient herself. The compressive dressing on the harvesting sites is kept in place for 5 days; then these areas are left exposed to the air. Major bruising of the harvesting site is common, and this is generally the most painful area in the immediate postoperative period. The breast is also swollen, but bruising is less marked. At the harvesting site, bruising clears in 3 weeks, sometimes leaving some firmer nodular areas that return to normal in the months after the procedure, and more rapidly if the patient massages them.

The breast attains its definitive volume 4 months after the procedure, but from the first month it is supple and soft to the touch. This technique enables made-to-measure corrections of the sequelae of conservative treatment. If correction is not sufficient, 1 or even 2 further sessions can be carried out after an interval of 3 to 4 months.

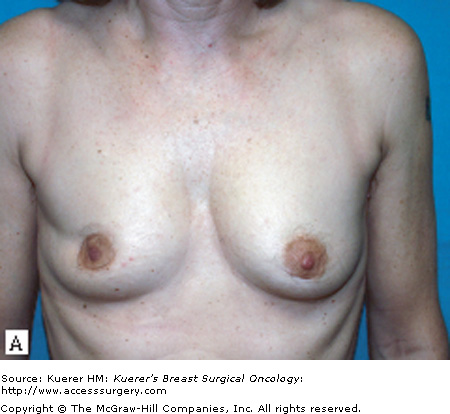

To date, our team has treated 70 patients according to this protocol. Last year, the results were assessed in 42 patients who had undergone lipomodeling for the sequelae of conservative treatment between May 2002 and March 2007.7 Their mean age was 50.7 years at the time of treatment, with a range of 35 to 64 years, and their mean body mass index was 21.8.

Fifty-four procedures were carried out in 42 patients, a mean of 1.3 per patient; 22% of patients required a second procedure, and only 1 patient required a third (2.4%).

During the first session of lipomodeling, a mean of 274 mL of fat was harvested (minimum 120 mL; maximum 480 mL). After centrifugation, the mean volume of fat recovered was 187 mL (71.2% of the volume centrifuged, with 28.8% lost during the process). The mean quantity reinjected was 166 mL, with a range of 76 to 302 mL. The results were assessed by 2 surgeons by clinical examination and from the photographic records of each patient before and after the procedure, and 93% were considered good or very good (Fig. 78-4). These results can be judged from the photographs (Fig. 78-5) but are even more striking on clinical examination. Ninety percent of patients were satisfied or very satisfied.