Abstract

Contraception refers to the deliberate use of methods or techniques to prevent pregnancy. Modern contraceptives include hormonal and no hormonal methods available in a variety of delivery systems. This chapter reviews the effectiveness and mechanisms of action of the methods currently marketed, side-effect profiles, and noncontraceptive benefits of available methods.

Keywords

Unintended pregnancy, Pearl Index, long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), hormonal contraception, postcoital contraception, barrier contraception

Introduction

- ◆

Forty-five percent of pregnancies in the United States are unintended.

- ◆

The most widely used contraception method is the oral contraceptive pill.

- ◆

Use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) is limited by cost, access, and education; removal of these barriers results in dramatic uptake up these methods.

The use of modern contraceptives has contributed substantially to the reduction of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality and to the ability of women to contribute to society. However, effective use of the methods has not been fully realized, as approximately 45% of all pregnancies in the United States, nearly 3 million pregnancies per year, are unintended. Unintended pregnancy has negative effects on maternal and newborn health, limits the educational potential of women, and requires significant financial resources from individuals and society.

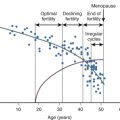

According to the US census bureau, 62 million American women are in the childbearing years (15 to 44 years old), the vast majority of whom are sexually active and trying to avoid pregnancy. The two contributors to unintended pregnancy are contraceptive non-use and contraceptive failure.

Table 36.1 demonstrates the changes over time in American contraceptive use and underscores that although long-term contraceptive methods are increasing in use, these methods still make up a slim minority of contraceptive technologies used by American women. The oral contraceptive pill is the most widely used method by women in their teens and 20s, women who have never been married, and women who have at least a college degree. Poor and low-income women are twice as likely as higher-income women to use the 3-month injectable method, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Fifty percent of all women age 40 to 44 years old who practice contraception have been sterilized.

| Method | 1982 | 1988 | 1995 | 2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | |

| Sterilization | 34.1 | 10,295 | 39.2 | 13,686 | 38.6 | 14,942 | 37.0 | 14,200 |

| Female | 23.2 | 6998 | 27.5 | 9614 | 27.7 | 10,727 | 27.1 | 10,400 |

| Male | 10.9 | 3298 | 11.7 | 4069 | 10.9 | 4215 | 9.9 | 3800 |

| Pill | 28.0 | 8431 | 30.7 | 10,734 | 26.9 | 10,410 | 28.0 | 10,700 |

| Implant | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.3 | 515 | 1.1 | 400 |

| Injectable * | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3.0 | 1146 | 3.2 | 1200 |

| Intrauterine device | 7.1 | 2153 | 2.0 | 703 | 0.8 | 310 | 5.5 | 2100 |

| Diaphragm | 8.1 | 2436 | 5.7 | 2000 | 1.9 | 720 | — | — |

| Male condom | 12.0 | 3608 | 14.6 | 5093 | 20.4 | 7889 | 16.1 | 6200 |

| Foam | 2.4 | 711 | 1.1 | 371 | 0.4 | 161 | — | — |

| Periodic abstinence | 3.9 | 1166 | 2.3 | 806 | 2.3 | 883 | 0.9 | 300 |

| Withdrawal | 2.0 | 588 | 2.2 | 778 | 3.0 | 1178 | 5.2 | 2000 |

| Other † | 2.5 | 754 | 2.1 | 733 | 1.3 | 508 | 0.4 | 200 |

| Total | 100.0 | 30,142 | 100.0 | 34,912 | 100.0 | 38,663 | 100.0 | 38.241 |

* Ring and Patch included in this row for 2008 data.

† Other includes emergency contraception, female condom or vaginal pouch, foam, cervical cap, Today sponge, suppository or insert, jelly or cream (without diaphragm), and other methods.

The proportion of women who use a contraceptive method at first intercourse has doubled in recent times to 79% at present. The majority of contracepting couples use condoms at first intercourse. Teenagers who do not use a contraceptive at first intercourse are twice as likely to become parents during adolescence as teenagers who do use a contraceptive method.

As demonstrated by Table 36.1 , contraceptive use has increased overall among American women. Recently, after years of underutilization, LARC use has also increased among American women. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a large prospective cohort study conducted by Washington University in St. Louis, found that 75% of women chose a LARC method when financial, access, and knowledge barriers were eliminated. Adolescents chose LARC methods nearly as often as adult women, and women of all age groups were less likely to discontinue these methods within 12 months and more likely to express satisfaction; a resulting decline in unintended pregnancy rates was observed.

Contraceptive Effectiveness Versus Efficacy

- ◆

A method’s effectiveness refers to its performance with perfect compliance; its efficacy refers to performance with typical use.

- ◆

The Pearl Index is the number of contraceptive failures per 100 women-years of use.

The term effectiveness is defined as the ability of a contraceptive to prevent pregnancy in a clinical trial setting, or with perfect compliance. Efficacy is the ability of a contraceptive to prevent pregnancy with typical use. The terms perfect use failure rate and typical use failure rate are also used to describe these concepts, respectively. Table 36.2 demonstrates the differences in the typical use failure rate and perfect use failure rate for each contraceptive method.

| Women Experiencing an Unintended Pregnancy Within the First Year of Use (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Typical Use * | Perfect Use † | Women Continuing Use at 1 Year ‡ (%) |

| No method § | 85 | 85 | 42 |

| Spermicides ǁ | 29 | 15 | 43 |

| Withdrawal | 27 | 4 | 51 |

| Periodic abstinence | 25 | — | — |

| Calendar | — | 9 | — |

| Ovulation method | — | 3 | — |

| Sympto-thermal ¶ | — | 2 | — |

| Postovulation | — | 1 | — |

| Cap ** | |||

| Parous women | 32 | 26 | 46 |

| Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 | 57 |

| Sponge | |||

| Parous women | 32 | 20 | 46 |

| Nulliparous women | 16 | 9 | 57 |

| Diaphragm ** | 16 | 6 | 57 |

| Condom †† | |||

| Female (reality) | 21 | 5 | 49 |

| Male | 15 | 2 | 53 |

| Combined pill and minipill | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Evra patch | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| NuvaRing | 8 | 0.3 | 68 |

| Depo-Provera | 3 | 0.3 | 56 |

| Lunelle | 3 | 0.05 | 56 |

| IUD | |||

| Progestasert (progesterone T) | 2 | 1.5 | 81 |

| ParaGard (copper T) | 0.8 | 0.6 | 78 |

| Mirena (LNG-IUS) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 81 |

| Norplant and Norplant-2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 84 |

| Female sterilization | 0.5 | 0.5 | 100 |

| Male sterilization | 0.15 | 0.1 | 100 |

| Emergency contraceptive pills: Treatment initiated within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse reduces the risk of pregnancy by at least 75%. ‡‡ LAM is a highly effective, temporary method of contraception. §§ | |||

* Among typical couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason.

† Among couples who initiate use of a method (not necessarily for the first time) and who use it perfectly (both consistently and correctly), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason.

‡ Among couples attempting to avoid pregnancy, the percentage who continue to use a method for 1 year.

§ The percentages becoming pregnant in columns 2 and 3 are based on data from populations where contraception is not used and from women who cease using contraception to become pregnant. Among such populations, about 89% become pregnant within 1 year. This estimate was lowered slightly (to 85%) to represent the percentage who would become pregnant within 1 year among women now relying on reversible methods of contraception if they abandoned contraception altogether.

ǁ Foams, creams, gels, vaginal suppositories, and vaginal film.

¶ Cervical mucus (ovulation) method supplemented by calendar in the preovulatory phase and basal body temperature in the postovulatory phase.

** With spermicidal cream or jelly.

‡‡ The treatment schedule is one dose within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse, and a second dose 12 hours after the first dose. Both doses of Plan B can be taken at the same time. Plan B (1 dose is 1 white pill) and Preven (1 dose is 2 blue pills) are the only dedicated products specifically marketed for emergency contraception. The Food and Drug Administration has in addition declared the following 17 brands of oral contraceptives to be safe and effective for emergency contraception: Ogestrel or Ovral (1 dose is 2 white pills), Alesse, Lessina, or Levlite (1 dose is 5 pink pills), Levlen or Nordette (1 dose is 4 light-orange pills), Cryselle, Levora, Low-Ogestrel, or Lo/Ovral (1 dose is 4 white pills), Tri-Levlen or Triphasil (1 dose is 4 yellow pills), Portia or Trivora (1 dose is 4 pink pills), Aviane (1 dose is 5 orange pills), and Empresse (1 dose is 4 orange pills).

§§ However, to maintain effective protection against pregnancy, another method of contraception must be used as soon as menstruation resumes, the frequency or duration of breastfeeding is reduced, bottle feeds are introduced, or the baby reaches 6 months of age.

Contraceptive clinical trials typically report their failure rates either by the Pearl Index or by Life Table Analysis. The Pearl Index is defined as the number of contraceptive failures per 100 women-years of exposure, and it uses as the denominator the total months or cycles of exposure from the initiation of the product to the end of the study or the discontinuation of the product. Life Table Analysis, on the other hand, provides the contraceptive failure rate for each month of use and can provide a cumulative failure rate for any specific length of exposure. A US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) briefing explained that the Pearl Index does not take into account the effect of failures over time. The Life Table Analysis method of reporting effectiveness is considered an actuarial method. Effectiveness can be difficult to compute because there are many factors that influence contraceptive use.

Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptives

- ◆

LARCs are nonpermanent methods that have action over a long period of time and do not require user action.

- ◆

Methods available in the United States include hormonal and copper intrauterine devices (IUDs) and subdermal hormonal implants.

- ◆

Increased availability and usage of LARCs has the potential to dramatically decrease unintended pregnancy rates in the United States.

Intrauterine Contraception

Intrauterine contraception is a method of reversible birth control widely used globally. Benefits of IUDs include a high level of effectiveness and efficacy, lack of associated systemic metabolic effects, the need for only a single act of motivation for long-term use, and the ability to be used over several years. The United States has seen a recent increase in IUD use. If this trend continues, it is likely that the increased use of IUDs will lower the unplanned pregnancy rate in the United States. Historically, a major barrier to uptake has been cost.

Currently there are two types of intrauterine contraceptives available on the United States market: the copper IUD and the levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine system.

Copper Intrauterine Devices

In the United States, the T380A IUD, or ParaGuard, is the only copper-bearing IUD on the market. The multiload CU375 is widely used in Europe. The T380A has a frame of polyethylene with a vertical length of 36 mm and a horizontal length of 32 mm. The amount of copper in the IUD is indicated by the number in its name, and corresponds to the length of time of efficacy. Copper dissolution accounts for the need to be replace the IUD over time. The amount of daily dissolution amounts to less than what the ingested amount of copper is in the normal diet. The copper T380A is currently approved in the United States for 10 years, but evidence has shown that it is effective for up to at least 12 years.

Copper IUDs have failure rates of less than 1% per year and cumulative 10-year failure rates of approximately 2% to 6%. A large World Health Organization trial reported a cumulative 12-year failure rate of 2.2% for the T380A. This is an average of 0.18% per year over 12 years of use. This failure rate is equivalent to that seen with female sterilization methods.

The mechanism of action of the copper IUD is multifaceted. Primary is the spermatotoxicity of ionized copper in uterine luminal fluid; this inhibits the mobility of spermatozoa, and its ability to perform the acrosomal reaction and fertilize the ovum. Destruction of oocytes and embryos secondarily contributes to the contraceptive effect. Action on the endometrium results in an inflammatory reaction toxic to embryos, and decreases the ability of successful blastocysts to undergo implantation.

Copper IUD users may experience irregular, heavy, or prolonged bleeding, particularly during the first months of use. Menstrual blood flow may increase by up to 74%, and heavier, more painful periods account for a 9% discontinuation rate at 3 years. The increase in blood flow is thought to be due to an increase in endometrial prostaglandins, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to be effective, both as prophylaxis and treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. Benefits have also been seen with antifibrinolytic and antidiuretic drugs.

Hormonal Intrauterine Devices

Hormonal IUDs currently available in the United States are T -shaped levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS). Four such devices on the market in the United States—Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta—offer varying levonorgestrel doses, lengths of efficacy, and device sizes.

The Mirena LNG-IUS measures 32 mm both horizontally and vertically. It is made with a silicone reservoir containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel in the IUD body. There is an initial burst release of levonorgestrel of 20 µg/day, resulting in plasma levels of 150 to 200 pg/mL. The plasma concentration of levonorgestrel decreases over the number of years it is used. There is sufficient levonorgestrel in the Mirena IUD to last at least 5 years.

The Liletta system is also a 32 mm by 32 mm device containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel, and provides comparable daily doses and resulting plasma levels of levonorgestrel as the Mirena. While currently approved in the United States for 3 years of use, its similarities to the Mirena suggest that its effectiveness may extend to 5 years, and clinical trials are underway to evaluate the its effectiveness for 7 years of contraception.

Kyleena is a 30 mm by 28 mm device containing 19.5 mg of levonorgestrel that was approved by the FDA in September 2016 for 5 years of use. In vivo studies indicate an average levonorgestrel release rate of 9 µg/day, with release rate decreasing over the device’s lifetime.

Skyla is a progestin-releasing IUD that contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel and provides 3 years of contraception. The device releases about 14 µg of levonorgestrel per day shortly after insertion. After 3 years, the device releases about 5 µg of levonorgestrel per day. The inserter has a diameter of 3.8 mm, which is about 1 mm smaller than the Mirena inserter. This device may be of use for women who do not need 5 years of contraception and for some nulliparous women where a narrower inserter may facilitate the placement of the device.

The LNG-IUS works primarily by thickening the cervical mucus and changing the endometrial lining. Thick cervical mucus obstructs the passage of sperm through the cervix. High concentrations of progestins are produced in the endometrium; this progestin-dominant effect allows the endometrium to remain thin and nonproliferate. The foreign body reaction also makes the environment hostile to sperm and eggs. While the frequency of ovulation is reduced with the LNG-IUS overall, this is not the primary mechanism of action. Women may ovulate variably with the LNG-IUS in place. Return to fertility after LNG-IUS removal occurs at the same rate as discontinuation of barrier methods of contraception. Pregnancy outcomes including term delivery, spontaneous abortion, and ectopic pregnancies after IUD removal is unchanged from the baseline incidence of these events in the population.

Considerations for Intrauterine Device Placement

Considerations that should be reviewed with patients before IUD placement include the timing of insertion, the bleeding patterns to be expected, the side effects of the method, and the expected interval of use. There are very few contraindications to IUD use; appropriate candidates for the IUD include women who desire long-term contraception regardless of age or parity.

The insertion of an IUD during menstruation lends some benefits, including lubrication and slight opening of the cervical os from the menstrual flow, a decrease in bleeding symptoms after IUD placement due to the preexisting bleeding from the menses, and the assurance that the patient is not pregnant. However, IUDs may be inserted at any time during the cycle so long as pregnancy has been excluded. The copper IUD is an effective postcoital contraceptive as well so it can be placed after unprotected intercourse and used long-term.

Bleeding patterns may change with both intrauterine contraceptive methods. The copper-T 380A is associated with an approximately 55% increase in menstrual blood loss. The bleeding patterns with the T380A IUD may be most increased during the first few months of use, and some patients may require supplemental iron and prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors during menses to help counteract these effects.

In contrast, the amount of blood loss is significantly reduced to about 5 mL per cycle with the LNG-IUS. Bleeding patterns with the LNG-IUS are variable, generally with unscheduled bleeding during the first few months of use due to the erratic thinning of the endometrium. Over time, bleeding days decrease and approximately 20% of women are amenorrheic at 1 year of use. Women who do experience menstrual periods with the LNG-IUS in place generally have light periods or spotting as opposed to full menstrual flow. For women who find unscheduled bleeding following LNG-IUS insertion unacceptable, naproxen may be effective; low-dose mifepristone has also been shown to improve bleeding patterns, but is not available in appropriate doses in the United States.

Rare but potential complications of IUD insertion include expulsion, infection, and perforation. Expulsion is the most common complication of IUD placement, and while not particularly dangerous, its detection is important so that the woman can use a back-up method of pregnancy prevention. Risk factors for expulsion include nulliparity, menorrhagia, prior expulsion, age less than 20 years, insertion immediately after a second trimester abortion, or postpartum insertion. There is a 3% to 10% annual risk of expulsion. Monthly string checks and warning signs should be reviewed so that early detection of expulsion is maximized.

A transient increase in the risk of infection within the first 20 days of IUD placement has been documented. This is likely due to the introduction of bacteria into the upper genital tract with the placement of the IUD or with sounding of the uterus. However, over time, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) prevalence is the same with IUD users as in the general population. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend that, for women who have been screened for gonococcal and chlamydial infection according to current guidelines, additional screening prior to IUD insertion is not necessary. For women who have not been screened according to guidelines, testing may be done at the time of insertion, and women who test positive may be given standard treatment with no need for IUD discontinuation. Women with known active gonococcal or chlamydial infection, purulent cervicitis, or active PID should not initiate IUD use, but these conditions do not necessitate IUD removal. As with all nonbarrier methods of contraception, patients should be counseled that the intrauterine system does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, and if such a risk is present, condoms should be used.

Perforation is another uncommon risk of IUD insertion. Perforation occurs at the time of insertion at a rate of approximately 1 in 3000 insertions. This risk is due to the blind introduction of the device into the uterus. At any time, if an IUD is found to be outside the uterus, even in asymptomatic patients, it should be removed from the peritoneal cavity. The presence of the copper or levonorgestrel IUD in the peritoneal cavity has been associated with complications including severe adhesions and bowel obstruction.

While exclusive breastfeeding confers contraceptive benefits for the first 6 months postpartum, many breastfeeding women do not do so exclusively, or desire additional contraception. Although still low, breastfeeding women have a 6- to 10-fold increased risk of perforation during IUD insertion when compared to nonbreastfeeding, postpartum women. However, breastfeeding does not introduce additional risk of other complications such as expulsion, removal due to bleeding or pain, or cervical laceration. Breastfeeding women tolerate copper IUDs as well as other nonhormonal contraceptive methods, and have fewer adverse effects after copper IUD insertion than those who choose methods such as the vaginal ring or subdermal implant. IUD use during breastfeeding has no effect on milk production, breastfeeding continuation, or infant growth.

Pregnancies are rare with an IUD in place given their efficacy. However, women who conceive while using an IUD and do not have the device subsequently removed face an incidence of spontaneous abortion of about 55%, an approximately threefold increase above pregnancies without an IUD in place. If a woman wishes to continue the pregnancy, the IUD should be removed. Ultrasound guidance and other techniques may improve the safety and ease of removing the IUD without endangering the pregnancy.

In addition to protection against endometrial and cervical carcinoma, the LNG-IUS’s noncontraceptive benefits include a decrease in menstrual symptoms and bleeding, control of endometrial hyperplasia, and reduction of pain with adenomyosis and endometriosis.

Contraceptive Implants

Implants allow for long-acting reversible contraception without a pelvic exam and regardless of shape and size of the uterus. Subdermal implants were first introduced to the United States market in 1990 with FDA approval of Norplant. Norplant is a sustained release progestin-only system that consists of six capsules that contain a total of 216 mg of levonorgestrel, and is effective for over 9 years of use. While it no longer available on the US market, Norplant is widely used in other parts of the world.

Nexplanon is currently the only subdermal contraceptive implant available in the United States. Nexplanon (and its predecessor, Implanon) is a progestin-only method that contains 68 mg of 3-ketodesogestrel (etonogestrel) within a single 4-cm flexible rod. It releases 60 to 70 mg of etonogestrel per day; this gradually decreases over time. In clinical use, Nexplanon can be inserted within 5 days of the onset of the menstrual cycle in a cycling woman and in the setting of a negative human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) in a noncycling woman. The etonogestrel implant is FDA-approved for 3 years, but evidence suggests it may be effective for up to 4 years. Insertion is accomplished in the outpatient setting—the capsule is implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of the arm through a trocar that is enclosed in the contraceptive implant kit. Nexplanon (but not Implanon) is radiopaque to aid in retrieval of implants that are difficult to locate.

The major mechanism of action of subdermal implants is ovulation inhibition by suppressing the midcycle surge of luteinizing hormone (LH). Ovulation is suppressed within 8 hours of implant insertion, and resumes within 3 to 4 weeks of removal. As with all progestin-only methods, the cervical mucus is thickened and the endometrial lining becomes decidualized. The effects on the endometrial lining produce the clinical symptoms of initial irregular, unscheduled bleeding followed by scant bleeding or amenorrhea. Amenorrhea rates with etonogestrel implants in clinical trials are about 50% of women. Frequent and prolonged bleeding occurred in 20%.

Studies have shown that the discontinuation of etonorgestrel implants due to abnormal bleeding may be as high as 23% within the first 2 years of use; still, users of the single-rod etornogestrel implant report fewer bleeding episodes and less blood loss per episode than users of Norplant. For women who experience irregular bleeding following etonorgestrel implant initiation and desire medical intervention, some evidence supports the use of mefenamic acid, mifepristone with estradiol or doxycycline, doxycycline alone, or tamoxifen. The most common adverse effects with the implant were acne, breast pain, and headache. Rare cases of device expulsion and migration have been reported, including migration to the pulmonary artery secondary to intravascular insertion. If the device is ever found not to be palpable, it should be located and removed.

Etonogestrel implant is safe for immediate postpartum insertion, both in women who do and do not intend to breastfeed, with improved long-term pregnancy prevention when compared with other postpartum methods. It is also approved for use immediately after miscarriage or abortion. Evidence suggests that etonorgestrel concentrations reach therapeutic levels regardless of body mass index (BMI), and that Nexplanon is therefore safe and effective in women of any BMI.

Oral Contraceptive Pills

- ◆

Oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) contain progestin with or without estrogen, and work by providing negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis.

- ◆

The estrogen component of combined hormonal contraceptives contributes to risk of deep venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke.

Hormonal contraception was initially marketed in the United States in pill form in 1960. While the oral contraceptive pill is still the most widely used hormonal contraceptive delivery system, steroid contraceptives are also available as a transdermal patch, vaginal ring, and 3-month injectable, as well as the previously discussed subdermal implant and intrauterine system. The oral contraceptive pill remains the most studied and best understood; its properties are assumed to apply to other delivery systems except when noted otherwise.

There are three main formulations for oral hormonal contraception: monophasic combination pills, multiphasic combination pills, and progestin-only pills.

Pharmacology

The progestins found in hormonal contraceptives are most commonly a derivative of 19-nortestosterone progestin. These progestins more closely resemble testosterone than their common alternative, the 21-carbon acetoxyprogesterone derivatives, which include medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) and megestrol acetate. 19-nortestosterone derivatives are orally active and carry some androgenic and progestational effects.

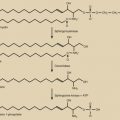

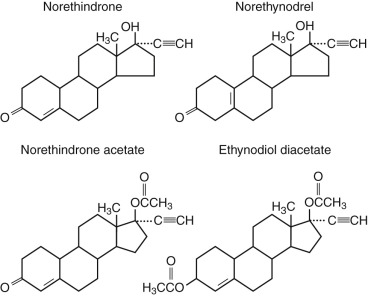

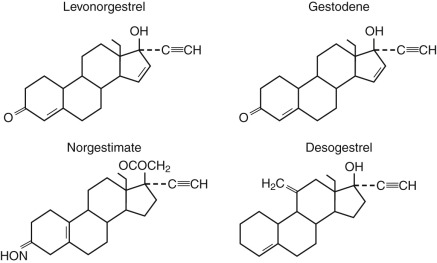

The two classes of progestins most commonly used are the estranes and gonanes. Those derived from 17α-acetoxyprogesterone are referred to as the pregnanes. The estrane family of progestin are norethindrone derivatives ( Fig. 36.1 ) and include norethindrone, norethynodrel, norethindrone acetate, ethynodiol diacetate, lynestrenol, norgestrel, norgestimate, desogestrel, and desogen. Norethindrone is the active metabolite of estrane progestins. The gonane family of progestins, the norgestrel progestins ( Fig. 36.2 ), include desogestrel, gestodene, norgestimate, levonorgestrel, and etonogestrel, and are used in the combination vaginal ring. Drospirenone is a progestin used in oral combination hormonal contraception but is not a member of the estrane or gonane families. Drospirenone is derived from spironolactone, and while it has antiandrogenic and antimineralocorticoid activity, it is considered to have less androgenicity than the 19-nortestosterone-derived progestins. Still, this formulation has not been shown to have decreased progestin-associated side effects in randomized control trials at a population-based level.

The progestin component of combined hormonal contraception is what is responsible for the contraceptive efficacy. Because the gonane class has greater progestational activity per unit weight than the estrane class, a smaller dose is required in these oral contraceptive formulations.

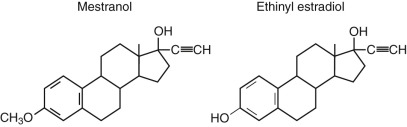

In combination hormonal contraceptive pills, progestin is combined with one of two types of estrogen: the more common ethinyl estradiol ( Fig. 36.3 ). The original oral contraceptive formulations contained 50 µg mestranol, and are termed first generation. These forms are rarely used today, and most oral contraceptives now contain estrogen doses of 35 µg or less and are referred to as low dose. OCPs with 20 to 35 µg of ethinyl estradiol are termed second-generation products. The third-generation formulation refers to those with the newer versions of the levonorgestrel derivatives and gonane progestins, including desogestryl, norgestimate, and gestodene.

Combination oral contraceptives are given continuously for 3 weeks with a medication-free fourth week. The withdrawal of estrogen in the combined hormonal contraceptives results in endometrial sloughing, resulting in a withdrawal bleed that usually lasts 3 to 4 days. Uterine blood loss is about 25 mL, less than the average 35 mL that is lost with menses in an ovulatory cycle. Newer formulations have focused on diminishing or eliminating the pill-free week to allow for a decreased number of bleeding days or elimination of bleeding days entirely.

Mechanism of Action

The progestin component of the combination pills prevents ovulation by inhibiting gonadotropin secretion. This is secondary to the progestational agent’s suppression of LH secretion. The estrogenic agent suppresses follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). However, it is important to note that even if follicles do develop, which is commonly seen with combination pills of 20 µg or less, these follicles do not develop sufficiently and the progestational component still inhibits the LH surge that is necessary for ovulation. The progestin component also works by thickening the cervical mucus and altering the endometrium such that it is not receptive to implantation. The endometrium in a progestin-dominant milieu is decidualized and atrophic. These lower genital tract effects are sufficient in and of themselves to afford good contraception. In fact, many progestin-only methods work primarily by cervical mucus thickening and endometrial lining decidualization.

Continuous Cycle Oral Contraceptives

The FDA has approved three contraceptive formulations for continuous use. These methods are called Lybrel, Seasonale, and Seasonique, but not all are currently marketed. The efficacy of these regimens appears to be similar to the 21/7-day regimen efficacy. The clinical trials that were done initially for the approval of these formulations demonstrate that continuous use of hormonal contraception suppresses folliculogenesis at improved rates over the traditional 21/7-day regimens, making it a good choice in patients with ovarian cysts who would benefit from suppression of follicle growth.

Studies have demonstrated that these formulations are acceptable to women of reproductive age. They are highly convenient, with fewer bleeding days over time. Noncontraceptive benefits include decreased dysmenorrhea, decreased endometriosis pain, and fewer instances of headaches, bloating, and mood swings. All women are good candidates for continuous hormonal contraceptives, but they may be particularly beneficial to women who have symptoms in their pill-free week. Breakthrough bleeding is, however, more common than during the first 3 months of use in the conventional 21/7-day regimen. Over time, this breakthrough bleeding reaches the usual rate. A Cochrane review of traditional 21/7-day administration versus continuous administration showed no difference in efficacy, safety profiles compliance rate, or satisfaction, and found fewer reports of headaches, genital irritation, feelings of fatigue, bloating, menstrual pain, mood perturbations, and pelvic pain with continuous hormonal contraception.

In women who had undergone ablation for endometriosis and have failed traditional 21/7-day low-dose monophasic contraception for suppression of pain, continuous low-dose monophasic contraceptives significantly reduced frequency and severity of pain. Continuous OCPs suppress both the ovary and the endometrium to a greater extent than cyclic OCPs and have been shown to have beneficial effects on both pain and mood symptoms related to menstruation. No endometrial hyperplasia or cancers were reported in clinical trials. Triglycerides and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) were similar in range for women on continuous hormonal contraception as those who were cycling.

Return to fertility appears to be fairly prompt after continuous hormonal oral contraception is discontinued. In a study of Lybrel, 99% of women were ovulating within 90 days of discontinuing the 365-day per year pill; 92% ovulated within 60 days, and 38.5% ovulated within 30 days of discontinuation.

It is important to note that although the FDA has approved these three formulations for extended use, many physicians have been using extended cycle regimens for their patients for years. Most monophasic hormonal contraceptive pills will produce acceptable results when used continuously.

Side Effects

Despite potential risk, women with contraindications to estrogen (between 2% and 16% of all reproductive-age women) use combined hormonal contraceptives at a rate similar to healthy women.

Metabolic Effects

The vast majority of metabolic effects of synthetic steroids—including effects on lipids, carbohydrate metabolism, and other hormonally responsive organs such as the breasts—are transient and minor. Rarely, these effects result in serious consequences. Table 36.3 shows the chemical and clinical effects that estrogens and progestins have on the human metabolic system.

| Steroid | Chemical Effects | Clinical Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Estrogen: Ethinyl Estradiol | ||

| Proteins | ||

| Albumin | ↓ | None |

| Amino acids | ↓ | None |

| Globulins | ↑ | — |

| Angiotensinogen | — | ↑ Blood pressure |

| Clotting factors | — | Hypercoagulability |

| Carrier proteins (CBG, SHBG, TBG, transferrin, ceruloplasmin) | — | None |

| Carbohydrate | ||

| Plasma insulin | ↑ | None |

| Glucose tolerance | ↓ | None |

| Lipids | ||

| Cholesterol | ↑ | None |

| Triglyceride | ↑ | None |

| HDL cholesterol | ↑ | ? ↓ Cardiovascular disease |

| LDL cholesterol | ↓ | ? ↓ Cardiovascular disease |

| Electrolytes | ||

| Sodium excretion | ↓ | Fluid retention |

| Vitamins | — | Edema |

| Vitamin B complex | ↓ | None |

| Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) | ↓ | None |

| Vitamin A | ↑ | None |

| Other | ||

| Breast | ↑ | Breast tenderness |

| Endometrial steroid receptors | ↑ | Endometrial hyperplasia |

| Skin | ↓ | ↓ Sebum production |

| Progestins: 19-Nortestosterone Derivatives | — | ↑ Facial pigmentation |

| Proteins (SHBG) | ↓ | None |

| Carbohydrate | ||

| Plasma insulin | ↑ | None |

| Glucose tolerance | ↓ | None |

| Lipids | ||

| Cholesterol | ↓ | None |

| Triglyceride | ↓ | None |

| HDL cholesterol | ↓ | ? ↑ Cardiovascular disease |

| LDL cholesterol | ↑ | ? ↑ Cardiovascular disease |

| Other | ||

| Nitrogen retention | ↑ | ↑ Body weight |

| Skin—sebum production | ↑ | ↑ Acne |

| CNS effects | ↑ | Nervousness, fatigue, depression |

| Endometrial steroid receptors | ↓ | No withdrawal bleeding |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree