Contact Dermatitis

Andrew J. Scheman

A skin condition commonly encountered by physicians is allergic contact dermatitis. With new chemical sensitizers being introduced into our environment constantly, physicians will be evaluating more instances of this disease. Contact dermatitis is the most common occupational disease and, as such, is of importance to both the individual and to society. The patient with allergic contact dermatitis may be very uncomfortable and have poor quality of life. Inability to pursue employment or recreation is common, especially if there is a delay in diagnosis and removal from exposure.

Immunologic Basis

The classification of immunologic hypersensitivity reactions is reviewed in Chapter 17 on drug allergies. Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IVa1, T-cell–mediated hypersensitivity. Type IVa1 allergy is also referred to as delayed-type hypersensitivity, reflecting the fact that typical reactions occur 5 to 25 days after initial exposure (1) and 12 to 96 hours after subsequent exposures. In contrast, immediate hypersensitivity is a type I immunoglobulin E(IgE) humoral antibody-mediated reaction, generally occurring withing 1 hour or less.

Whereas the typical skin lesion in immediate hypersensitivity is urticarial, typical allergic contact dermatitis is eczematous (1). Thus, skin lesions can include vesicles, bullae, and poorly-demarcated erythematous scaly plaques acutely and, when chronic, lichenification. It is important to realize that contact allergy is often morphologically and histologically identical to other forms of eczema, including atopic dermatitis and irritant contact dermatitis, which is defined as nonimmunologic damage to the skin caused by a direct toxic effect. Therefore, patch testing is usually needed to distinguish contact allergy from other types of eczema.

Typically, immediate hypersensitivity is caused by parenteral exposure through ingestion or respiratory exposure through inhalation. An exception is immunologic contact urticaria, in which a type I reaction is induced by topical exposure. The typical type IVa1 contact allergy is induced by topical exposure. An exception occurs with systemic ingestion of a contact allergen that reproduces skin lesions caused by a previous external exposure to the same or a similar substance; this is termed systemic contact dermatitis. The list of substances capable of causing type I allergy is different from the list of substances capable of causing type IVa1 allergy. There are a few substances, such as penicillin, quinine, sulfonamides, mercury, and arsenic that have can cause both IVa1 contact hypersensitivity and type I immediate hypersensitivity reactions.

Although atopic individuals are prone to type I allergies, they been generally considered not to be more likely to develop type IVa1 allergy than nonatopic individuals. On the other hand, it has been clearly demonstrated that atopic persons are much more likely to have a lowered threshold for developing irritant contact dermatitis.

Sensitization

The inductive or afferent limb of contact sensitivity begins with the topical application to the skin of a chemically reactive substance called a hapten. The hapten may be organic or inorganic and is generally of low molecular weight (<500 daltons)(1). Its ability to sensitize depends on penetrating the skin and forming covalent bonds with proteins. The degree of sensitization is directly proportional to the stability of the hapten–protein coupling. In the case of the commonly used skin sensitizer dinitrochlorobenzene, the union of the chemical hapten and the tissue protein occurs in the Malpighian layer of the epidermis, with the amino acid sites of lysine and cysteine being most reactive (2). It has been suggested that skin lipids might exert an adjuvant effect comparable with the myoside of mycobacterium tuberculosis.

There is strong evidence that Langerhans cells are of crucial importance in the induction of contact sensitivity (3). These dendritic cells in the epidermis cannot be identified on routine histologic sections of the skin by light microscopy, but they can be easily visualized using

special stains. They possess MHC class II and B7 homology receptors B7(CD80/86).

special stains. They possess MHC class II and B7 homology receptors B7(CD80/86).

Elicitation

Langerhans cells are dendritic epidermal cells that possess MHC Class II antigen on their surface. The Langerhans cell ingests the hapten–protein complex, processes it, and then produces a resulting peptide that binds to the HLA-DR antigen on the surface of the cell. The peptide is then presented to a CD4+ helper T-cell type 1 (TH1) with specific complementary surface receptors.

The binding of the TH1 cell induces the Langerhans cell to release cytokines including interleukin-1(IL-1). IL-1 in turn activates the bound TH1 cell to release interleukin-2 which leads to T-cell proliferation. The proliferating T cells magnify the response by releasing interferon-γ, which leads to increased HLA-DR display on Langerhans cells and increased cytotoxicity of T cells, macrophages, and natural killer cells. The sensitized TH1 cells also result in an anamnestic response to subsequent exposure to the same antigen. Type IVa1 hypersensitivity can be transferred with sensitized TH1 cells (4).

Contact allergy involves both T effector cells leading to hypersensitivity and T suppressor cells leading to tolerance. The net effect is the balance of these two opposing inputs. Cutaneous exposure tends to induce sensitization, whereas oral or intravenous exposure is more likely to induce tolerance. Once sensitivity is acquired, it usually persists for many years; however, it occasionally may be lost after only a few years. Hardening refers to either a specific or generalized loss of hypersensitivity due to constant low-grade exposure to an antigen. This type of deliberate desensitization has been successful only in rare instances and is therefore not recommended as a therapeutic strategy.

Histopathology

The histologic picture in allergic contact dermatitis reveals that the dermis is infiltrated by mononuclear inflammatory cells, especially about blood vessels and sweat glands (2). The epidermis is hyperplastic with mononuclear cell invasion. Frequently, intraepidermal vesicles form, which may coalesce into large blisters. The vesicles are filled with serous fluid containing granulocytes and mononuclear cells. In Jones-Mote contact sensitivity, in addition to mononuclear phagocyte and lymphocyte accumulation, basophils are found. This is an important distinction from hypersensitivity reactions of the TH1 type, in which basophils are completely absent.

Clinical Features

History

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs most frequently in middle-aged and elderly persons, although it may appear at any age. In contrast to the classical atopic diseases, contact dermatitis is as common in the population at large as in the atopic population, and a history of personal or family atopy is not a risk factor.

The interval between exposure to the responsible agent and the occurrence of clinical manifestations in a sensitized subject is usually 12 to 96 hours, although it may be as early as 4 hours and sometimes longer than 1 week. The incubation or sensitization period between initial exposure and the development of skin sensitivity may be as short as 2 to 3 days in the case of a strong sensitizer such as poison ivy, or several years for a weak sensitizer such as chromate. The patient usually will note the development of erythema, followed by papules, and then vesicles. Pruritus follows the appearance of the dermatitis and is uniformly present in allergic contact dermatitis.

Physical Examination

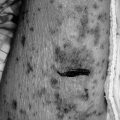

The appearance of allergic contact dermatitis depends on the stage at which the patient presents. In the acute stage, erythema, papules, and vesicles predominate, with edema and occasionally bullae (Fig. 30.1). The boundaries of the dermatitis are generally poorly marginated. Edema may be profound in areas of loose tissue such as the eyelids and genitalia. Acute allergic contact dermatitis of the face may result in a marked degree of periorbital swelling that resembles angioedema. The presence of the associated dermatitis should allow the physician to make the distinction easily. In the subacute phase, vesicles are less pronounced, and crusting, scaling, and early signs of lichenification may be present. In the chronic stage, few papulovesicular lesions are evident, and thickening, lichenification, and scaliness predominate.

Figure 30.1 The acute phase of contact dermatitis due to poison ivy. Note the linear distribution of vesicles. (Courtesy of Dr. Gary Vicik.) |

Different areas of the skin vary in their ease of sensitization. Pressure, friction, and perspiration are factors that seem to enhance sensitization. The eyelids, neck, and genitalia are among the most readily sensitized areas, whereas the palms, soles, and scalp are more

resistant. Tissue that is irritated, inflamed, or infected is more susceptible to allergic contact dermatitis. A clinical example is the common occurrence of contact dermatitis in an area of stasis dermatitis that has been treated with topical medications or sensitizing chemicals.

resistant. Tissue that is irritated, inflamed, or infected is more susceptible to allergic contact dermatitis. A clinical example is the common occurrence of contact dermatitis in an area of stasis dermatitis that has been treated with topical medications or sensitizing chemicals.

Differential Diagnosis

The skin conditions most frequently confused with allergic contact dermatitis are seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and primary irritant dermatitis. In seborrheic dermatitis, there is a general tendency toward oiliness of the skin, and a predilection of the lesions for the scalp, the T-zone of the face, midchest, and inguinal folds.

Atopic dermatitis (Chapter 29) often has its onset in infancy or early childhood. The skin is dry, although pruritus is a prominent feature, it appears before the lesions and not after them, as in the case of allergic contact dermatitis. The areas most frequently involved are the flexural surfaces. The margins of the dermatitis are indefinite, and the progression from erythema to papules to vesicles is not seen.

Psoriasis is characterized by well demarcated erythematous plaques with white to silvery scales; pruritus is often mild or absent. Lesions are often distributed symmetrically over extensor surfaces such as the knee or elbow.

The dermatitis caused by a primary irritant is a simple chemical or physical insult to the skin. For example, what is commonly called dishpan hands is a dermatitis caused by household detergents. A prior sensitizing exposure to the primary irritant is not necessary, and the dermatitis develops in a large number of normal persons. The dermatitis begins shortly after exposure to the irritant, in contrast to the 12 to 96 hours after exposure in allergic contact dermatitis. Primary irritant dermatitis may be virtually indistinguishable in its physical appearance from allergic contact dermatitis. It should be emphasized that skin conditions may coexist. It is not unusual to see allergic contact dermatitis caused by topical medications applied for the treatment of atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses.

A variant of contact allergy is contact urticaria (CU). There are three categories of CU: immunologic contact urticaria (ICU), protein contact dermatitis (PCD), and nonimmunologic contact urticaria (NCU). ICU is an immediate wheal-and-flare response generated by a wide variety of contactants. The immunopathogenesis of both ICU and PCD appears to be mediated at least in part by antigen-specific IgE and type I hypersensitivity. The immunopathologic mechanisms in PCD other than type I are unclear. Several authors have reported Type IV cutaneous reactions corroborated by positive patch tests (5). NCU is caused by some allergens such as fragrances and benzyl alcohol known to cause immunologic reaction; however, in the case of NCU, the etiology is unclear.

Identifying the Offending Agent

History and Physical Examination

Once the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis is made, vigorous efforts should be directed toward determining the cause. A careful, thorough history is absolutely mandatory. The temporal relationship between exposure and clinical manifestations must be kept in mind as an exhaustive search is made for exposure to a sensitizing allergen in the patient’s occupational, home, or recreational environment. The location of the dermatitis most often relates closely to direct contact with a particular allergen. At times this is rather straightforward, such as dermatitis of the feet, caused by contact sensitivity to shoe materials or dermatitis from jewelry appearing on the wrist, the ear lobes, or the neck. The relationship of the dermatitis to the direct contact allergen may not be as obvious at other times, and being able to associate certain areas of involvement with particular types of exposure is extremely helpful. Contact dermatitis of the face, for example, is often due to cosmetics directly applied to the area. One must keep in mind other possibilities, however, such as hair dye, shampoo, and hair-styling preparations. Contact dermatitis of the eyelid, although often caused by eye shadow, mascara, and eye liner, also may be caused by nail polish. Involvement of the thighs may be caused by keys or coins in pants pockets. Therefore, it is vital that the physician be familiar with various distribution patterns of contact dermatitis that may occur in association with particular allergens.

Frequently, the distribution of the skin lesions may suggest a number of possible sensitizing agents, and patch testing is of special value. Certain allergens may be airborne, and exposure may occur by this route. Dermatitis among farmers caused by ragweed oil sensitivity occurs occasionally. Smoke from burning the poison ivy plant may contain the oleoresin as particulate matter, and thus expose the sensitive individual. Forest fire fighters develop generalize allergic contact dermatitis from smoke from the burning branches and leaves containing urushiol. Another route of acquiring poison ivy contact dermatitis without touching the plant is by indirect contact with clothing or animal fur containing the oleoresin. It should be remembered also that systemic administration of a drug or a related drug that has been previously used topically and to which the patient has been sensitized can elicit a localized or generalized eruption. An example is sensitivity to ethylenediamine. A patient may have developed localized contact dermatitis to topically applied ethylenediamine hydrochloride previously used as a stabilizer in such compounds as Mycolog cream. After being sensitized, a localized or

generalized eruption may then occur when aminophylline is administered orally (6).

generalized eruption may then occur when aminophylline is administered orally (6).

The oral mucosa also may be the site of a localized allergic contact reaction resulting in contact stomatitis or stomatitis venenata (7). The relatively low incidence of contact stomatitis compared with contact dermatitis is attributed to the brief duration of surface contact, the diluting and buffering action of saliva, and the rapid dispersal and absorption because of extensive vascularity. Agents capable of producing contact stomatitis include dentifrices, mouthwashes, dental materials such as acrylic and epoxy resins, and foods. The clinical response is most commonly inflammation of the lips, but cases of “burning mouth” syndrome have also been attributed to contact allergy.

Patch Testing

Principle

Patch testing or epicutaneous testing is the diagnostic technique of applying a specific substance to the skin with the intention of producing a small area of allergic contact dermatitis. It can be thought of as reproducing the disease in miniature. The patch test is generally kept in place for 48 hours (although reactions may appear after 24 hours in markedly sensitive patients), and then observed for the gross appearance of a localized dermatitis (most commonly after 48 and 96 hours). The same principles of proper interpretation of a positive patch test apply as in the case of the immediate wheal and erythema skin test reaction (Chapter 4). A positive patch test is not absolute proof that the test substance is the actual cause of dermatitis. It may reflect a previous episode of dermatitis, or it may be without any clinical relevance at all. The positive patch test must always correlate with the patient’s history and physical examination.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Indications for Patch Testing

All unexplained cases of eczema that either do not respond to treatment or recur after treatment may be due to contact allergy and should be considered for patch testing (9). Currently, patch testing is the only accepted scientific proof of contact allergy. If patch testing is successful at identifying a causative allergen, avoidance often will be curative. Alternatively, if the causative agent is not identified, it is likely that the patient will need ongoing treatment and that treatment will be less than optimal.

A thorough history and physical examination should be performed with emphasis on the distribution and timing of the clinical lesions. Once this information is obtained, an exhaustive history should be taken to identify all potential allergens that had opportunity to come in contact with the skin of the patient. A tray of patch test materials is then assembled.

Most physicians doing patch testing use the TRUE Test, a ready-made series of 23 common allergens that can be easily applied in a busy office setting (Table 30.1). Since a recent study reported that less than 26% of contact allergy problems will be fully solved using the TRUE Test, patients often need referral to a physician specializing in patch testing. These specialists will generally have a wide array of allergens relevant to most occupations and exposures and are familiar with where these allergens are found and alternatives to avoid exposure. Testing is usually performed with an expanded standard tray and additional allergens individualized to the patient exposure.

Table 30.1 Allergens on the True Test Standard Tray Listed by Function | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The physician should become familiar with the potent sensitizers and with the various modes of exposure. It is important to keep in mind the possibility of cross-reactivity to other allergens because of chemical similarities. Sensitivity to paraphenylenediamine, for example, also may indicate sensitivity to para-amino-benzoic acid and other chemicals containing a benzene ring with an amino group in the “para” position.

The most common cause of Type IVa1-delayed hypersensitivity allergic contact dermatitis in the United States is Toxicodendron (poison ivy, poison oak, poison sumac). In contrast, latex-induced contact dermatitis is a Type I contact uritcaria which affects health

care workers, patients with spina bifida, and manufacturing employees who prepare latex-based products. Table 30.2 is a list of some of the most potent sensitizers and agents that contain them. It is by no means complete, and is not intended as a general survey. More detailed information on other sensitizers, environmental exposures, and preparation of testing material is contained in several standard references (10–12).

care workers, patients with spina bifida, and manufacturing employees who prepare latex-based products. Table 30.2 is a list of some of the most potent sensitizers and agents that contain them. It is by no means complete, and is not intended as a general survey. More detailed information on other sensitizers, environmental exposures, and preparation of testing material is contained in several standard references (10–12).

Table 30.2 Examples of Antigens and Exposure Commonly Causing Contact Dermatitis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Techniques

The two most common types of patch test chambers, the aluminum Finn chamber and the plastic IQ chamber, come in strips that hold 10 allergens (9). Allergens are placed into the chambers as a drop of liquid on filter paper or as a 1-cm cylinder of allergen in petrolatum from a syringe. With the patient standing erect, the patch test strips are applied starting at the bottom and pressing each allergen chamber firmly against the skin as it is applied. The skin surrounding the patch test strips is then outlined with either fluorescent ink or gentian violet marker. Reinforcing tape, and sometimes a medical adhesive such as Mastisol, is then used to further affix the patches in place. The patch test series is documented in the medical records clearly showing the position of each allergen. The patient should be instructed to keep the patch test sites dry and avoid vigorous physical activity until after patch test reading is completed. The allergens are removed and read 48 hours after application and the patient returns for a second reading of the patch tests commonly at 72 or 96 hours, with the 96-hour test being preferred by this author. Some physicians also do readings at 1 week after application to identify more delayed reactions.

It is essential that the skin of the back be free of eczema at the time of testing to avoid false-positive reactions due to what has been called the angry back syndrome. It is also important that the testing site has not been exposed to topical steroids or ultraviolet light during the preceding week. Oral steroids should be avoided when possible; however, some strong patch test reactions can be obtained even when a patient is taking up to 20 mg prednisone daily.

Photoallergy and Photopatch Testing

When an eruption is observed in a sun-exposed distribution, photoallergic contact dermatitis should be considered. Photoallergy is identical to allergic contact dermatitis with the exception that the allergen in contact with the skin must be exposed to ultraviolet A (UVA) light for the reaction to occur. Photopatch testing is performed similar to routine patch testing, but a second identical set of allergens is also applied to the back. Approximately 24 hours after application, one set of allergens is uncovered and exposed to 15 joules of

UVA light. The patches are then carefully reapplied. All patches are then removed at 72 hours and read at 96 hours. A photoallergy is confirmed if only the site exposed to UVA light shows a reaction. If both the exposed and unexposed sites show equal reactions, a standard contact allergy is confirmed. A stronger reaction at the site exposed to UVA indicates contact allergy augmented by coexisting photoallergy.

UVA light. The patches are then carefully reapplied. All patches are then removed at 72 hours and read at 96 hours. A photoallergy is confirmed if only the site exposed to UVA light shows a reaction. If both the exposed and unexposed sites show equal reactions, a standard contact allergy is confirmed. A stronger reaction at the site exposed to UVA indicates contact allergy augmented by coexisting photoallergy.

Patch Testing Reading and Interpretation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree