The last few decades have seen unprecedented advances in the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with breast cancer. This prodigious growth in knowledge and information has necessitated a shift toward increased specialization within each discipline, such that those with a specific interest in breast cancer have been able to focus their efforts toward achieving a high level of expertise in their specialty. Without question, the end result of this specialization has been a greater refinement of cancer care and dramatically improved outcomes for patients with breast cancer; the 5-year survival rate for a woman diagnosed with breast cancer between 1975 and 1979 was 74.9%, compared with 87.7% for a woman diagnosed between 1995 and 2000.1

The growing recognition of the importance of multidisciplinary care has also mandated the creation of health care delivery systems that foster and support collaboration among specialists. The comprehensive breast center has been a model for coordinated multidisciplinary care, and this concept is even more timely now than when the Van Nuys Breast Center opened its doors almost 30 years ago. The goals of a breast center, whether real or virtual, remain excellence in the delivery of breast health care within a multidisciplinary environment, although substantial variations among centers exist around additional goals such as education, outreach, and research. Here, we will discuss the advantages favoring the treatment of breast cancer within such an infrastructure, consider the metrics by which performance and quality can be assessed, and review the individual components vital to ensuring the success of such a center, for both patient outcome and community impact.

The increased number of treatment options coupled with the growing complexity of multidisciplinary cancer care has resulted in a growing awareness of the importance of coordinated cancer care. In addition, concurrent with these changes in medical treatment, enormous changes in the fabric of American society coalesced to create a demand for greater patient involvement in all aspects of health care decision-making and patients were empowered to seek treatment in the most comprehensive care environments. Breast cancer treatment has been at the forefront of this challenge, since the effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for breast cancer had been empirically shown for several decades in randomized clinical trials of radiation therapy for women undergoing lumpectomy as well as for systemic treatment in women with surgically resected locoregional disease. By combining access to screening, diagnosis, and multimodal therapy within one setting, comprehensive breast centers were an attractive model of care, and indeed, the emergence of coordinated breast programs has facilitated the achievement of 2 primary goals: (1) delivery of patient-centered care and (2) delivery of improved quality care for patients with breast disease.

Until the middle of the 20th century, the mainstay of treatment for breast cancer was the radical mastectomy described by Sir William Halsted in the 1890s.2 However, in the 1960s and 1970s, powerful forces of social and political reform were set in motion by several seminal events that brought breast cancer and breast cancer treatment into the spotlight of public awareness. These were the exciting early years of the women’s movement, where, for the first time, women’s issues took center stage. Beginning in the 1960s, mammography became more widespread and this new technology was hailed for its ability to diagnose cancers that were so small that they had previously been undetectable. Then, in 1974, First Lady Betty Ford as well as Happy Rockefeller, the wife of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, announced to the nation that they had both been diagnosed with breast cancer. Not only was such personal disclosure unprecedented in the history of presidential politics, but the public acknowledgement of breast cancer and its treatment, and the resulting increase in public awareness, mobilized the country to a heightened level of health advocacy never before encountered. Together, these powerful forces brought about a reexamination of the treatment for breast cancer. Largely as a result of public advocacy, the surgical option of lumpectomy for breast cancer was considered. Numerous prospective randomized trials subsequently confirmed that there was no significant survival advantage to mastectomy over lumpectomy and radiation.

Now more than ever, it is critical to provide a coordinated, patient-centered framework to guide patients through the complex decisions to be made when grappling with a breast cancer diagnosis. In the prior model of care, patients would be required to seek consultations from numerous providers at multiple separate medical sites. In the ideal model of a comprehensive breast center, the multidisciplinary resources and expertise required to treat the patient are all brought to bear within the same infrastructure, making for a more unified, streamlined, and coordinated experience for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with breast disease.

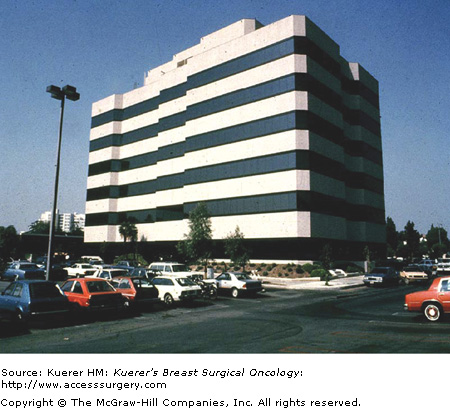

One of the first attempts to create such an environment for patients with breast cancer was exemplified by the Van Nuys Breast Care Center envisioned by a breast surgeon, Mel Silverstein (Fig. 6-1). The Van Nuys Center was a free-standing multidisciplinary outpatient clinic that incorporated breast imaging, breast surgeons, and oncologists under one roof, all sharing a deep philosophical commitment to improving the fragmented nature of breast cancer care and to creating a warm and respectful environment to support their patients. In the 19 years the center was open, over 3100 patients were treated for breast cancer, with outstanding results.3 Although it eventually shut its doors due to declining reimbursement rates, it remains an innovative demonstration of what could be achieved in creating a patient-centered experience for breast cancer care.

Figure 6-1

Van Nuys Breast Care Center, one of the first multidisciplinary breast centers in the country, opened in 1979. For almost 2 decades under the guidance of its medical director Dr. Mel Silverstein, the center was a leader in providing innovative, evidence-based, patient-centered care for women diagnosed with breast cancer and their families. A. The Van Nuys Breast Center Building. The center occupied the top floor and half of the floor below. B. Patient waiting area. Great attention to detail was taken to create a warm, patient-centered environment. (Photos courtesy of Mel Silverstein.)

An equally important consideration favoring treatment in multidisciplinary centers is the ongoing drive to improve the quality of breast cancer care delivery. Increasingly, the current environment puts a premium on quality benchmarks for health care. Furthermore, both patients and payors are searching for effective ways in which health care reimbursement could be tied to quality metrics. Thus, it has become essential to invest resources into the development of an efficient and cost-effective infrastructure, develop rational quality metrics, and create a system in which quality can be measured and the effects of interventions assessed. Studies of volume–outcome relationships have been reported, with large case volume often serving as a surrogate for the presence of an organized breast cancer program. When choice of surgery is evaluated as an end point, it has been clearly shown that increased rates of breast-conserving procedures are seen in larger-volume hospitals or those associated with a cancer center.4-6 Furthermore, when adjusted for case mix, both overall survival and breast cancer–free survival were improved in large centers, compared to small facilities.7,8 Such studies clearly demonstrate both a higher rate of adoption of new findings (eg, use of lumpectomy) as well as an improved outcome arc associated with breast cancer treatment at large-volume centers.

Unlike the NCI requirements for Comprehensive Cancer Center designation, there are currently no nationally established accreditation requirements for a comprehensive breast care center. However, there has been a substantial international effort to move toward defining standards for what constitutes a “Specialist Breast Unit.” These criteria have been defined by the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer–Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (EORTC–BCCG) and the European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA) in a position paper published in 2000.9 This paper outlined general recommendations for the essential components of a Breast Unit, including core clinical staff requirements, affiliation with a population breast screening program, and presence of outreach clinics for adjoining areas with low population density. In addition, the suggestion was made to have a case volume requirement of greater than 150 new cancer cases treated annually to ensure a sufficient caseload to maintain clinical expertise. The paper also stipulated that the unit establish written protocols for the management of each stage of breast cancer, a requirement that some in the United States have found unnecessarily rigid given the exigencies of continuous advances in treatment options and individual patient preference.10 Nevertheless, this position paper serves as a useful template on which to design the infrastructure of multidisciplinary breast centers, and suggests guidelines upon which future accreditation of such centers can be based.

We are witnessing a sea change within the health care industry, where the provision of and reimbursement for care as well as the benchmarks for determining the quality of care are undergoing continuous change and ever closer scrutiny. Increasingly, quality measures will be linked to payment, and thus the selection of the best metrics for assessing the quality care are critically important and must require input from all stakeholders, including patients and health care providers. Numerous organizations have presented broad guidelines of how quality should be determined, with some outlining specific criteria by which to assess breast cancer treatment. In an effort to standardize quality measures as well as to make progress toward data collection of meaningful metrics, experts representing the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) convened and were successful in defining quality measures for two common cancer sites: breast and colorectal.

The panel achieved consensus on three breast cancer measures (Table 6-1).11 These standards were selected from a much larger group of measures derived from the NCCN cancer treatment guidelines as well as from the NICCQ project comparing cancer treatment practices,12 and these 3 were selected on the basis of 2 criteria: (1) potential to impact breast cancer outcome and (2) feasibility of accurate end-point collection. These metrics have been adopted by numerous other organizations including the Cancer Program Standards of the American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer (ACoS), National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality (NICCQ), and the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO). This represents an important first step in establishing universal quality metrics for breast cancer treatment, and these guidelines have already been implemented for ACoS Cancer Center commendation as well as individual provider performance measures. Clearly, more metrics will follow, and leadership will be required to standardize quality measures and data collection across different organizations and practice settings. Provider participation in the selection of these measures is critical to ensuring that the quality metrics remain timely, meaningful, and relevant to current breast cancer treatment. Multidisciplinary breast centers will no doubt play an important role as they will be best positioned to disseminate adherence to quality measures and to collect high-quality outcome data, since many measures will doubtless span disciplines.

| Numerator | Denominator | Estimated Yearly Denominator in the United States | Estimated Risk of Recurrence in the Measure: Specified Measurement Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient received tamoxifen or AI within 1 year of diagnosis | Stage I-III

| 153,302 | 3% node negative |

ER or PR positive

| 9% node positive | ||

| Patient started breast radiation therapy following lumpectomy within 1 year of diagnosis | Stage I-III | 134,000 | 1% with XRT |

| Age 18-70 years | 6% no XRT | ||

| Patient received adjuvant chemotherapy within 120 days of diagnosis | Stage II-III | 38,000 | 3% |

| ER and PR negative | |||

| Age 18-70 years |

The multidisciplinary nature of breast care and cancer treatment invites collaboration and a team approach to providing care. The ideal of this team approach aspires to a goal where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, but the quality and expertise of each of the individual team components are of critical importance (Table 6-2).

| Administrative/Institutional Commitment | Clinical Team (Personnel) | Physical Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

| Medical director | Physicians | Breast imaging facilities |

| Business manager | Breast imagers | Infusion center |

| Marketing director | Genetic counselors | Operating suites |

| Office for billing and collections | Oncologic surgeons/reconstructive surgeons | Radiation oncology facilities |

| IT support and integration | Medical oncologists | |

| Cytologists/surgical pathologists | Outpatient clinic space | |

| Radiation oncologists | Conference facilities | |

| Psychologists/psychiatrists | Physician and staff office space | |

| Clinical nurses | Resource center | |

| Breast imaging technicians | Volunteer office | |

| Radiation oncology technicians | ||

| Physical therapists | ||

| Medical assistants | ||

| Scheduling staff |

Of the many advances made in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, one of the most impactful has been the mammographic detection of early nonpalpable breast cancer. Population-based screening programs have estimated an overall mortality benefit of over 20% in favor of women undergoing screening mammography.13,14 Thus, a critically important mission of a comprehensive breast program is to provide state-of-the-art breast imaging capabilities for screening, diagnosis, and evaluation of breast lesions. Historically, free-standing breast screening centers have been successful, but increasingly, such breast imaging programs have been incorporated into a more comprehensive multidisciplinary setting.

Screen-film mammography, the long-time mainstay of breast imaging, is being rapidly supplanted by digital mammography units. Although overall performance of digital mammography has been comparable to full field screening mammography, digital mammography can be more accurate in certain subgroups of the screened population, such as in women with dense breast tissue and in premenopausal women.15,16 In addition, digital mammography may be more sensitive in the detection and characterization of microcalcifications.17 However, the greatest impetus for the adoption of digital mammography has been the growing need for less cumbersome radiographic data storage and retrieval. Furthermore, image transmission has been enormously facilitated by digital mammography, such that radiologic expertise can be accessed even from the most geographically remote sites. Ultrasound technology has also improved, and must be part of the expertise provided by a dedicated breast imager. Its use has been particularly effective in the workup of benign lesions as well as for delineating the extent of mammographically occult cancers. The sensitivity of radiographic screening has improved with the introduction of breast MRI, although arguably this gain has been achieved at the cost of reduced specificity.18-20 However, selective use of MRI for screening high-risk women,18,19,21 for work-up of a known cancer,22-24 or for evaluating the breast for an axillary metastasis with unknown primary25-27 have all been shown to be of value, and the use of breast MRI is expected to increase substantially in the coming decade.

A team approach to the patient at risk of breast cancer must include clinicians trained in both assessing the degree of breast cancer risk as well as advising patients in how best to manage this risk. With the ability to test for cancer susceptibility genes, patients at greatest risk for hereditary breast cancers can be identified early and counseled regarding the risk-reducing strategies that best fit the patient’s needs and preferences. Although BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most commonly encountered hereditary breast cancer susceptibility genes, genetic counselors specifically trained to assess familial breast cancer risk can detect more uncommon predispositions such as Cowden syndrome (PTEN mutation), Li–Fraumeni syndrome (P53 mutation), CDH1 mutations, and CHEK2 mutations. Such testing can have beneficial implications not only for the proband tested but for family members as well. Since breast cancer syndromes are associated with increased risk of other malignancies, the genetic counseling team must include clinical expertise from other specialists including gynecologic oncologists, gastroenterologists, and dermatologists. Infrastructure to support and track these patients is vital to the most rapid adoption of screening strategies, prevention interventions, and clinical trials for these high-risk individuals.

As briefly mentioned above, studies have shown both more rapid dissemination of treatment advances as well as improved overall and disease-free survival among patients treated by specialist breast surgeons.4,5,7,8,28 Over the last decade, such outcomes have engendered the recognition of breast oncologic surgery as a distinct specialty within surgical oncology. Concurrent with this development has been the establishment of an accredited program of breast surgery sponsored by the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO). Thirty-three SSO-approved breast surgery programs now exist in the United States and participate in a fellowship match. Moreover, many surgeons currently in practice and trained before the era of breast fellowships have focused their scope to predominantly breast surgery-based activities. Professional organizations such as the SSO, the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS), and the American Society of Breast Disease (ASBD) have been instrumental in fostering this specialization and have been successful in disseminating new techniques such as sentinel lymph node biopsy as well as research findings into the community.

Access to reconstructive surgeons is critical to the psychological and emotional well-being of many patients who undergo procedures that may substantially alter their physical appearance. While many women choose to decline breast reconstruction after mastectomy and are content with their decision, other women who choose mastectomy and reconstruction have been shown to experience the same long-term quality of life as those undergoing lumpectomy, a much less invasive procedure.29 Significant advances in breast reconstruction including autologous free flap reconstructive techniques as well as nipple-sparing mastectomy procedures can result in excellent cosmesis (Fig. 6-2).30,31 Collaboration between the oncologic and reconstructive surgeons in breast programs have allowed for better coordination of care, allowing fewer barriers to immediate breast reconstruction.

If a breast cancer patient were asked to identify “their doctor,” it would most likely be the medical oncologist. Although no single modality of treatment is dispensable, systemic treatment is clearly acknowledged to have the greatest potential impact on survival. The number of options in the breast cancer treatment armamentarium is tremendous and growing yearly. In addition, molecular prognostic and predictive tools are also proliferating, outstripping our ability to carefully consider how best to incorporate them into quality patient care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree