aPartial (peripheral) or total parenteral nutrition, antibiotics, enteral nutrition, somatostatin analog, and/or minimally invasive drainage.

bWith or without a drain in situ.

US, ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography scan; POPF, postoperative pancreatic fistula.

Taken from Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138(1):8–13.

Numerous risk factors contribute to fistula development. The most widely accepted risks include a soft pancreatic texture that does not hold sutures well for the pancreatic anastomosis in PD or sutures or staples for remnant closure in distal pancreatectomy, a small pancreatic duct (<3 mm diameter), poor nutritional status (albumin <3 g/dL), and high intraoperative blood loss (>1 L). Pancreatic surgeons have also examined different surgical techniques to avoid fistula formation. For PD, the technique used (e.g., duct to mucosa vs. invagination; routine placement of a pancreatic duct stent) or location (pancreaticojejunostomy (PJ) vs. gastrojejunostomy) of the pancreatic anastomosis has been examined. The results of numerous randomized trials and meta-analyses are mixed, with one favoring one technique or location over the other, or no difference observed. We routinely perform a partial invagination technique without the use of stents and have observed an overall fistula rate of less than 15% and a rate of about 7% after PD for pancreatic cancer.

For distal pancreatectomy, the incidence of pancreatic fistula ranges from 15% to 25%. Some studies suggest that the fistula rate is decreased with the use of stapled closure. More recently, there is some evidence that reinforced stapled closure, using a Seamguard, may further decrease the rate of fistula development. We routinely use stapled closure and Seamguard where possible but have found that even the 4.8-mm staples cannot completely seal a thick pancreas. In that case, the pancreas is transected with cautery, and a sutured closure of the cut surface is performed with a running and locking 3-0 Prolene suture and an additional suture (4-0 or 5-0 Prolene) to close the pancreatic duct. The incidence of pancreatic fistula is highest in patients undergoing middle (segmental) pancreatectomy ranging from 20% to 60%. This high incidence is due to the presence of both a closed pancreas surface toward the head of the pancreas and a pancreaticojejunal anastomosis of the distal segment.

Treatment

Pancreatic fistulas are associated with increased patient morbidity, hospital stay and costs, and even occasional death due to sepsis or hemorrhage. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential. Four goals of treatment will be reviewed. These include (a) good drainage, (b) treatment of infection, (c) maintenance of good nutritional status, and (d) correction of electrolyte imbalances.

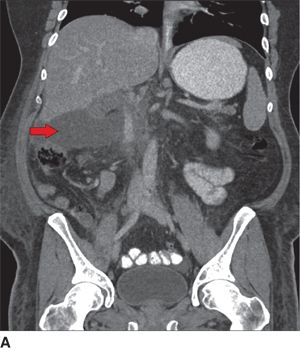

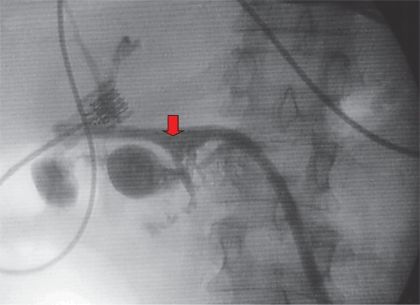

The most important treatment goal of pancreatic fistula management focuses on complete drainage of extraluminal pancreatic exocrine juices. We routinely place a closed-suction Silastic drain (10 flat or 19 round Jackson-Pratt) anterior to the PJ anastomosis. It is drawn behind the stomach and the left lobe of the liver, which usually maintains its proper position on top of the PJ suture line. It is cut long enough so that its tip lies next to the hepaticojejunostomy anastomosis; thus, it will drain a leak from either site effectively. If the drain output does not appear turbid or contain bile, the drain is routinely removed on postoperative day 5 to 7, when the patient is eating a regular diet. A high-volume output of serous fluid does not influence this decision, but if the character of the fluid is suspicious, the amylase level is checked. If a pancreatic fistula is present, the drain is left in place. If the patient’s white blood cell count is elevated, or if they are febrile, broad-spectrum antibiotics are started and a CT scan performed to look for any undrained fluid collections, which should be drained by the interventional radiologist with CT scan or ultrasound guidance (Fig. 9.1). The fluid is sent for culture and amylase concentration, and the antibiotics are then tailored to the specific organisms. Once all signs of infection resolve, the patient is discharged with the surgical drain (and any additional percutaneous drains) in place. Before discharge, around postoperative day 10, the drains are taken off of suction and allowed to drain into a plastic bag. The patient is seen within the next week in the clinic. The drains are removed if their output has been under 10 mL/d for a period of at least 2 to 3 consecutive days. If the fistula persists several weeks after discharge, we obtain a fistulagram and at that time replace the original drain with a red rubber catheter (Fig. 9.2). Occasionally, the tip of the original drain has migrated inside the lumen of the bowel. If this is the case, the replacement tube is positioned more superficially. This will hasten closure of the fistula, and the drain can be removed. If a low-output fistula (<50 mL/d) persists several weeks after drain exchange, rather than immediately removing the drain, it is backed out by 3 to 4 cm each week, so the fistula track can heal behind the drain. Using this strategy, we have never had to reoperate on a patient for a postoperative fistula after a PD.

FIGURE 9.1 Postoperative pancreatic fistula managed with a percutaneous drain. A. CT scan (coronal views) taken on postoperative day 6 after a pylorus-preserving Whipple resection for a duodenal cancer reveals a posterior leak from the pancreaticojejunostomy (arrow highlights intra-abdominal fluid collection). B. Repeat CT scan obtained 5 days after a percutaneous drainage catheter was placed reveals complete resolution of the collection and the tip of the radiology drain (arrow).

FIGURE 9.2 “Tubogram” reveals presence of pancreatic fistula. A tubogram obtained through a 16-Fr red rubber catheter 3 weeks after a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy reveals contrast filling the jejunum at the level of the pancreaticojejunostomy (arrow), confirming the presence of a pancreatic fistula.

The use of somatostatin for the prevention or treatment of postoperative pancreatic fistulas has been examined. Overall, it does not decrease fistula development, hasten its closure, or alter its morbidity. Somatostatin does decrease the fistula volume, which can help with management of electrolyte deficiencies, nutritional status, and skin breakdown in high-output fistulas. Short-acting somatostatin is administered as 100 μg subcutaneously three times per day; the long-acting variety, which is effective for 1 month, is preferred.

If a fistula persists for 2 to 3 months in patients who undergo distal pancreatectomy, despite drain exchange as described above, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and a pancreatic duct stent are indicated. The ERCP can confirm the site of the leak and identify any downstream ductal strictures that may contribute to the persistence of the fistula. Even without a stricture, a stent in the main pancreatic duct that traverses the duodenal papilla decreases the pressure in the duct, which likely hastens fistula closure. To avoid stent-related complications (migration, erosion, infection, stricture formation, etc.), the stent must be removed within 2 months at most.

If, despite all of these measures, the pancreatic fistula does not close after at least 6 months, then surgical internal drainage may be indicated. A fistulojejunostomy is created with a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb sewn to the fistulous tract as close to the pancreas as possible.

For nutritional support, patients with pancreatic fistulas should not be kept NPO but allowed to eat a regular diet. Studies have shown that enteric intake is associated with a higher rate of fistula closure. Serum albumin levels should be kept at greater than 3 to 3.5 g/dL. Occasionally, supplemental calories with TPN are required as an adjunct to oral intake to reach that nutritional goal. This is the case particularly in patients with nausea and ileus, which can accompany fistulas and may diminish patients’ appetites. Loss of pancreatic exocrine secretions may also be associated with electrolyte imbalances, as the fluid is rich in bicarbonate and other essential electrolytes. Serum electrolyte levels should be routinely monitored in patients in the hospital and after discharge.

DELAYED GASTRIC EMPTYING

Definition and Incidence

DGE is a common complication after PD. It is defined as high nasogastric (NG) tube output in the postoperative setting requiring that the tube be left in place for 10 or more postoperative days, emesis after NG tube removal necessitating replacement of the tube, or failure to progress to a regular diet without the use of prokinetics. DGE is not usually a serious event, but it does prolong hospital stay, temporarily worsens quality of life, and can occasionally lead to additional invasive procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree