Recently, the term integrative medicine has come into common use. The Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine has defined this term as the practice of medicine that reaffirms the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient, that focuses on the whole person, is informed by evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapeutic approaches, providers, and disciplines to achieve optimal health and healing.

Prevalence

In the United States, an estimated 44% of the population used at least one CAM therapy in 1997.2,4–6 According to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the prevalence of CAM use in the United States was approximately 38% for adults and 12% for children.7

Surveys published since 1999 suggest that between 25% and 83% of US adult cancer patients have used CAM therapies at some point after diagnosis, with variations in utilization rates depending on geographic area and type of cancer.8–25 Earlier studies generally report lower overall prevalence of CAM use (9% to 54%), possibly due to increasing rates of use or broadening of the definition of CAM.26,27 Initial studies of CAM prevalence during the 1970s and 1980s focused on the toxicity of the anticancer therapy laetrile. The reported prevalence of CAM was 9% to 16%,27 but surveys within the past decade estimated the prevalence of use in pediatric oncology to be 31% to 87%; moreover, in many cases, the treating physician was unaware that their patients were using CAM.28–31 Use of CAM is also prevalent among cancer patients outside the United States in all regions of the world, with significantly varying use among different regions.26,32,33

In the West, CAM use appears to be more common among those with higher education levels and higher incomes. CAM use is also higher among young females who have had surgery, used chemotherapy, or had a history of CAM use before diagnosis.19,32,34,35

ESTABLISHING AN INTEGRATIVE ONCOLOGY APPROACH WITH PATIENTS

Integrative Oncology Model

An integrative approach to cancer should be comprehensive, personalized, evidence-based, and safe. The conventional model of cancer treatment involves three different disciplines (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy), and integrative oncology aims to expand the interdisciplinary approach to include therapies such as acupuncture, yoga, meditation, diet, exercise, and other modalities. This is in response to the concept of treating the whole patient in all domains. Engel’s biopsychosocial model of health care, first published in Science more than 30 years ago, describes one conceptual model of these domains of patient care and its importance in the treatment of all patients.36 The Integrative Medicine Program at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center provides one example of how this framework may assist in creating comprehensive integrative care plans (Fig. 153.1). Without a comprehensive assessment and appropriate attention given to their needs, patients may perceive gaps in their care. Although symptoms such as severe pain or nausea are typically thought of as purely physical symptoms, if symptoms remain severe and chronic, they will often impact the psychosocial dimensions of health as patients may become more irritable, socially inactive, and fatigued due to insomnia. With comprehensive care plans, patients will have cancer treatments that address all of their needs in a more seamless manner. These plans will also have the greatest potential for improving the overall health and well-being of cancer patients. These basic comprehensive evaluations are aggregates of many different components; by addressing issues of nutrition, physical activity, symptom control, and other factors, these plans will help improve the performance of cancer patients throughout the continuum of care.

Physical Well-Being

Growing evidence supports the important role of physical activity and nutrition in the health of cancer patients, and these factors have been correlated with improved clinical outcomes. Moreover, several phytochemicals demonstrate pharmacologic effects on molecular targets in known cancer signaling pathways.37 The Women’s Intervention Study reported that a 24% reduction in fat intake resulted in lower cancer recurrence rates.38 Participants were randomized to increase fruit and vegetable intake and reduce dietary fat, but a significant reduction in breast cancer events was not found; however, when secondary analyses were performed, including physical activity, an increased survival of approximately 50% was found among women who were physically active and maintained a diet high in fruits and vegetables.39,40 Similar associations are beginning to be reported in colon cancer patients.39–42 The American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) and the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) have created a combined report for guidelines regarding nutrition and physical activity to prevent cancer; the American Cancer Society (ACS) has also published guidelines for those with cancer.43–48 Additionally, a recent study examining obesity during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients found obesity was correlated with decreased survival,49 and a different study found that obesity predicts a second primary tumor on the contralateral breast.50 Patients need to be encouraged to follow the ACS guidelines and the AICS/WCRF guidelines for cancer prevention and encouraged to adopt healthful behaviors in regard to physical activity and diet.

Psychosocial Well-Being: The Mind–Body Connection

The mind–body connection is an important aspect of integrative oncology, as emphasized in the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Cancer Care for the Whole Patient.”51 This comprehensive report states that “cancer care today often provides state-of-the-science biomedical treatment, but fails to address the psychological and social (psychosocial) problems associated with the illness. These problems—including . . . anxiety, depression or other emotional problems . . .—cause additional suffering, weaken adherence to prescribed treatments, and threaten patients’ return to health.” Extensive research has documented that mind–body interventions appear to address many of the issues mentioned in the IOM report.

The belief that what we think and feel can influence our health and healing dates back thousands of years.52 The importance of the role of the mind, emotions, and behaviors in health and well-being has been a part of medical traditions of the world, such as Chinese, Tibetan, and Ayurvedic medicine. Many patients with cancer turn to CAM therapies as a way to reduce stress; substantial evidence now shows the negative health consequences of sustained stress on health and well-being. The profound psychological and behavioral effects of stress may include post-traumatic stress disorder, increased health-impairing behaviors (e.g., poor diet, lack of exercise, substance abuse), poor sleep, and decreased quality of life.53–57 Research has shown that stress can also decrease compliance with regular health screening.58,59

Many stress-induced physiologic changes can have direct effects on health, including persistent increases in sympathetic nervous system activity and the hypothalamic–pituitary axis that can cause increased blood pressure, heart rate, catecholamine secretion, and platelet aggregation.60–65 Furthermore, research has associated stress with increased latent viral reactivation, upper respiratory tract infections, and wound-healing time.66–70 Stress also deregulates a variety of immune indices, as shown in both healthy subjects and cancer patients.71 Such stress-induced physiologic changes can affect cancer progression, treatment, recovery, recurrence, and survival.72,73 Spiegel et al.76 first published on the possible impact of a psychosocial intervention on breast cancer survival, but subsequent studies have not consistently reproduced these results.74,75,77 However, recent research has demonstrated a survival advantage among breast cancer patients who received psychological intervention with more than 10 years of follow-up78 as well as improved mood and quality of life during and after radiotherapy.79 These studies underscore the importance of psychosocial intervention in cancer treatment.

Patient–Clinician Communication Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Research indicates that neither adult nor pediatric patients receive sufficient information or discuss CAM therapies with physicians, pharmacists, nurses, or CAM practitioners.21,28 Most patients do not bring up the topic of CAM because no one asks; thus, patients may believe it is unimportant to disclose. It is estimated that 38% to 60% of patients with cancer are taking complementary medicines without informing their health-care team.8,80 This lack of discussion is of grave concern because biologically based therapies (such as herbs) may interact with cancer treatments. Patients are commonly unaware of the differences between U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved medications (which require evidence of efficacy, safety, and quality control in manufacturing) and supplements, which are governed not by the FDA but by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. Supplements under this legislation are exempt from the same scrutiny the FDA imposes on medications; furthermore, these supplements are not intended to treat, prevent, or cure diseases. The common belief by patients that natural means safe needs to be addressed with education as some herbs and supplements have been associated with multiple drug interactions81 as well as increased cancer risk and organ toxicity. These specific concerns are addressed later in this chapter.

Existing research suggests that the majority of cancer patients desire communication with their doctors about CAM,82 and there is general agreement within the oncology community that in order to provide optimal patient care, oncologists must not only be aware of CAM use, but also be willing and able to discuss all therapeutic approaches with their patients.83,84 It is the health-care professional’s responsibility to ask patients about their use of complementary medicines,85 and the discussion should ideally take place before the patient starts using a complementary treatment—whether it is a nutritional supplement, mind–body therapy, or other CAM approach.

A number of strategies can be used to increase the chance of a worthwhile dialogue.86 One approach is to include the topic of CAM as part of a new patient assessment. For example, when asking about medications, physicians should inquire about everything the patient ingests—including over-the-counter products, vitamins, minerals, herbs, and even the patient’s diet. Physicians may consider having the patient bring in the actual bottles of herbs and supplements for evaluation. When asking about a patient’s past medical history, physicians may ask other health-care professionals to determine if the patient has visited with naturopathic or chiropractic practitioners. If the issue of CAM arises, clinicians need to develop an empathic communication strategy that addresses the patient’s needs while maintaining an understanding of the current state of the science. In other words, this strategy needs to be balanced between clinical objectivity and bonding with the patient so that it can benefit both the patient and the health-care provider. These patients need reliable information on CAM from evidence-based resources such as Natural Standard Research Collaboration (www.naturalstandard.com), as well as adequate time to discuss this information with their oncologists.

Safety Concerns

Many CAM therapies can potentially cause adverse outcomes, and are thus a major concern among health-care professionals.87–90 Nonbiologically based CAM therapies, such as massage or acupuncture, often have minimal risks when performed by trained health professionals. In contrast, herbs and supplements should be considered more similar to prescription medications in that they have the potential to have powerful effects on the natural biologic processes of the body. This is especially true when natural plants are processed into concentrated formulations. The pathways by which CAM therapies may lead to negative clinical outcomes include metabolic interactions, treatment interactions, direct organ toxicity, direct biologic effects on the cancer, and unregulated low quality manufacturing of biologically based CAM. Some of these topics are briefly reviewed here.

Metabolic Interactions

Many botanical agents are pharmacologically active, raising concerns about pharmacodynamic effects that can lead to changes with conventional therapy, such as cytotoxic agents.87 Published data are available regarding potential interactions between specific herbs or vitamins and prescription drugs.87,88,91–97 Overall, there is substantial clinical evidence of herb–drug interactions in general.81 Therefore, negative interactions should be considered prior to integrating herbs, vitamins, or nutritional supplements during chemotherapy.

Common chemotherapy agents metabolized through the cytochrome P-450 system and the specific isoenzymes responsible for their metabolism are a starting point to consider possible interactions. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) is of particular concern, with multiple well-documented drug interactions. This herb appears to inhibit the hepatic enzyme cytochrome P-450 3A4 acutely, then induce it with repeated administration. A study of individuals given irinotecan (CPT11) reports a greater than 50% reduction in serum levels of the active metabolite SN38 after concomitant administration of St. John’s wort.98 Imatinib levels appear to be altered by similar mechanisms.99 St. John’s wort and similar herb–chemotherapy combinations should be used with extreme caution because of the potential for alterations in drug metabolism.

The common practice by patients of combining compounds, in which there is a lack of data regarding the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, creates a dangerous situation that may lead to inadvertent detrimental impact on clinical outcomes. This possible negative impact must be evaluated and discussed with patients whenever considering the use of untested natural products with other therapies.

Treatment Interactions

Antioxidant Interference with Chemotherapy or Radiation. Because oxidative damage to cells may increase the risk of cancer, the use of antioxidant herbs and vitamins has been proposed for cancer treatment or prevention. Examples include vitamins A, C, and E, as well as lycopene, green tea, soy, grape seed extract, melatonin, and selenium. Concern has been raised that antioxidants may interfere with radiation therapy or some chemotherapy agents (e.g., alkylating agents, anthracyclines, or platinums), which themselves can depend on oxidative damage to tumor cells for their cytotoxic effects. Studies of the effects of antioxidants on cancer therapies have yielded mixed results, with some reporting antagonistic effects, others noting synergism (i.e., benefits), and most suggesting no significant interaction.89,90,100,101 A large randomized trial of head and neck cancer patients evaluated the use of beta-carotene and vitamin E for the reduction of radiation side effects.102 Results found a reduction in side effects, but also found decreased survival among patients taking beta-carotene and vitamin E. Additionally, the use of these antioxidants seemed to correlate to an increase in second primary cancer.103 Whether antioxidants are beneficial or harmful is a critical question without a clear scientific answer at this time; rather, it remains an area of continuing study and controversy.104,105

Direct Organ Toxicity

Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity. The long-term use of concentrated natural products is an increasing concern. A recent report evaluating the risk for end-stage renal disease in Taiwan found that chronic use of traditional Chinese medicine herbs carried an increased risk of kidney failure.106 Multiple herbs and supplements may cause hepatotoxicity or transaminitis based on human research or known hepatotoxic constituents and should be used cautiously in combination with other hepatotoxic agents (Table 153.2).

Hematologic Toxicity

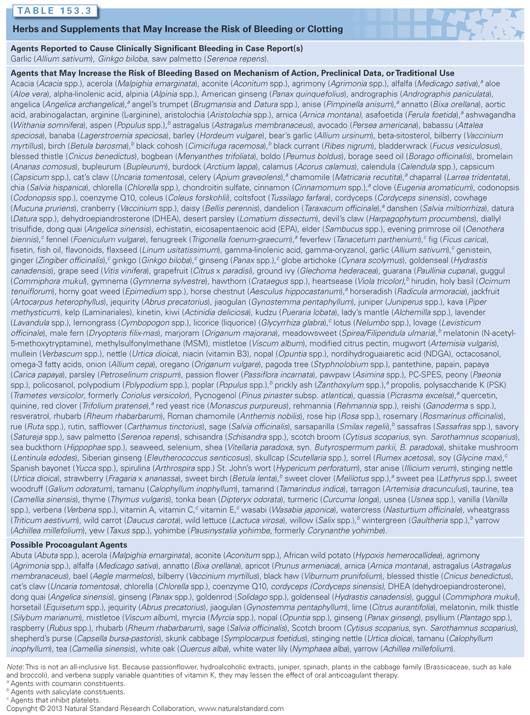

Many herbs and supplements carry an increased risk of bleeding. Multiple case studies have reported clinically significant bleeding with the use of Ginkgo biloba (either alone or with aspirin or warfarin), and isolated case reports of bleeding with the use of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), fish oil, and garlic (Allium sativum).81 The suspected mechanism for increased bleeding is interference with platelet function. Because herbal supplementation is common among cancer patients, surgical staff should screen patients presurgically for use of herbal and other dietary supplements. These agents should be discontinued before surgical procedures, and should be used cautiously with other agents that increase the risk of bleeding. Clinicians should also be cautious about taking natural products concurrently with warfarin, which is known to be sensitive to vitamin K intake and possible drug interactions. Numerous other herbs and vitamins may increase bleeding risk based on known constituents, preclinical data, or traditional use (Table 153.3).

Direct Biologic Effects on Cancer

A common concern is the potential for herbs and supplements to have procancerous effects. One clear example comes from Sidney Farber from Harvard University and the discovery of antifolate agents such as methotrexate, which came from the observation that folic acid supplementation actually promoted disease progression.107 Until appropriate clinical trials have been completed on herbs and supplements for individual types of cancer, the resulting impact—whether beneficial, harmful, or neither—will remain unknown, and thus, caution will always be considered a prudent approach.

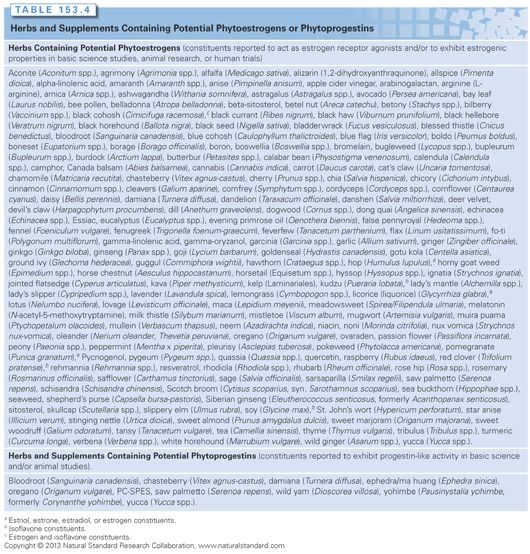

Phytoestrogens. Phytoestrogens are plant-based compounds structurally similar to estradiol and capable of binding to estrogen receptors as agonists or antagonists. Multiple popular herbs contain phytoestrogens, such as black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa), red clover (Trifolium pratense), and soy (Glycine max) (Table 153.4). Although some epidemiologic evidence has found reduced breast cancer risk associated with the consumption of phytoestrogens,108,109 effects of these agents in hormone-sensitive cancers remain unclear, and use in patients with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer is controversial (see the Soy section, which follows, for further discussion).

The preparation of herbs and supplements can vary from manufacturer to manufacturer and from batch to batch within one manufacturer. Because the active components of a product are often not clear, standardization may not be possible, and the clinical effects of different brands may not be comparable. There may also be harmful contaminants in products not manufactured under good manufacturing practice (GMP). One example includes PC-SPES, an herbal formula for the treatment of prostate cancer. This product was taken off the market in 2002 by the FDA because different lots were found to contain warfarin, indomethacin, and estrogen diethylstilbestrol.110

SPECIFIC COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE THERAPIES

Many cancer therapies used are the same as those used in the general population for common noncancer indications such as St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) for depression, kava (Piper methysticum) for anxiety, Echinacea purpurea for common cold symptoms, or yoga, massage, and tai chi for overall well-being. This chapter lists some of the more common therapies about which oncologists might be questioned by their patients; this only represents a small sample of therapies. Several resources are available that can provide a summary of the available evidence regarding CAM therapies.

Biologically Based Therapies Used for Cancer Treatment and Secondary Prevention

Beta-Carotene

Two large randomized trials have been completed for the prevention of lung cancer: the Alpha-Tocopherol and Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Trial (ATBC) and the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET).111 Neither trial showed any efficacy of beta-carotene to prevent lung cancer among patients at elevated risk, primarily smokers or those with secondhand smoke exposure. Additionally, the ATBC study showed a trend toward increased risk for lung cancer. Both trials found a higher mortality rate among those randomized to beta-carotene supplementation. A meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials of beta-carotene supplement also indicated an increase in stomach cancer with daily supplementation of 20 mg or higher.112 Supplementation with beta-carotene is generally discouraged as a result of these studies.

Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinol/Ubiquinone)

Clinical Studies. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) has been studied for the prevention of anthracycline cardiotoxicity based on purported antioxidant effects, but without conclusive results. Cortes et al.113 observed 10 patients who received adriamycin and received CoQ10 at a dose of 50 mg per day. A decreased incidence of cardiac dysfunction was reported. In another study, 20 children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) who were treated with anthracyclines were randomized to CoQ10 therapy.114 There was decreased fractional shortening in both the CoQ10 treated and untreated groups, but no comparison was made between these two groups. The small sample size and poor study design limit the ability to draw firm conclusions.

Safety. High doses (greater than 300 mg per day) for long periods may elevate liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase).115 Concern also exists when CoQ10 is used with antihyperglycemic,116,117 psychiatric and cardiovascular agents, and warfarin or anticoagulants,118,119 based on conflicting evidence and secondary sources.120–122

Polysaccharide K

Clinical Studies. An uncontrolled trial of polysaccharide K (PSK; Trametes versicolor, formerly Coriolus versicolor) reported improved survival in cancer patients compared with historical controls.123 PSK has been reported to improve survival in colorectal,124 gastric,125,126 breast,127–130 esophageal,131–133 lung,134–136 hepatocellular,137 nasopharyngeal carcinoma,123,138 and in acute leukemia.139,140 However, other studies have reported no survival benefit with PSK as an adjuvant therapy.123,130,139,140 Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), Purified Protein Derivative (skin test agent; tuberculosis) (PPD), human leukocyte antigen A2 (HLA-A2), and human leukocyte antigen B40 (HLA-B40) have been reported to be associated with response to PSK therapy.127,141–148

Safety. PSK generally seems to have a low incidence of mild and tolerable side effects.124,129 Cases of liver impairment and toxicity have been noted with PSK use, and gastrointestinal upset, darkening of the fingernails, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and coughing have been reported with extended use of PSK.138,149–151 Theoretically, concomitant use of PSK with anticoagulants or antiplatelets could increase the risk of bleeding, although clinical evidence of this interaction is lacking.

Essiac Herbal Combination Tea

Clinical Studies. The original proprietary formula of Essiac contained burdock root (Arctium lappa), sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), slippery elm inner bark (Ulmus fulva), and Turkish rhubarb (Rheum palmatum). There is a lack of reliable research available on Essiac. Mouse studies at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in the 1970s were not formally published, and 86 human case reports collected retrospectively in 1988 by the Canadian Department of National Health and Welfare yielded unclear results.152

Safety. Concern has been raised about Essiac herbal tonic’s potential to stimulate the growth of human breast cancer cells through estrogen receptor–mediated as well as estrogen receptor–independent mechanisms of action. A 2004 systematic review did not identify any published clinical trials to evaluate this herbal complex in patients with cancer.152 Despite this lack of evidence, Essiac and Essiac-like products (which may contain additional herbs) remain popular among cancer patients. Rhubarb and sheep sorrel contain oxalic acid, which is known to cause hepatic and renal damage in high doses.

Ginger

Clinical Studies. Although some evidence supports the use of ginger (Zingiber officinale) for nausea or emesis during pregnancy,153–162 ginger’s effects on other types of nausea or emesis, such as chemotherapy-induced postoperative nausea or motion sickness, remain undetermined.163–169 Several randomized trials that utilized different doses of ginger along with standard antiemetics have found mixed results,166,169,170 although overall, the studies suggest that ginger is more effective than placebo.171 Thus, more studies are needed to further examine ginger therapy for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

Safety. The most frequent side effects associated with ginger use are gastrointestinal upset, heartburn, gas, and bloating. Estrogen receptor–positive patients should be cautious because ginger may also exert high estrogenic potency, based on in vitro evidence.172 Ginger may inhibit platelet aggregation or decrease platelet thromboxane production, thus theoretically increasing bleeding risk. When ginger was used in patients who were taking nifedipine, antiplatelet aggregation was increased, which suggests a synergistic effect on the inhibition of platelet aggregation.173

Ginseng

Clinical Studies. Ginseng (Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolius) is a common ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine herbal formulas, but few clinical trials have evaluated the use of ginseng alone as an anticancer agent. A clinical trial evaluating American ginseng to treat cancer-related fatigue found nonsignificant trends toward benefit in higher doses compared to placebo.173,174 Similarly, an improvement in quality of life was found in another smaller randomized clinical trial utilizing sun ginseng.175 A small study utilizing an American ginseng extract found a decreased length of respiratory symptoms.176 Further clinical trials are needed to determine if ginseng will be beneficial for cancer patients without interfering with cancer treatments.

Safety. The most frequent side effects associated with ginseng include headache, insomnia, and gastrointestinal toxicities.177 Concern exists when used in combination with diabetes medications (due to possible hypoglycemic properties), anticoagulants (due to increased risk of bleeding), monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and stimulants. Caution should be used when ginseng is taken with medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P-450 2D6.

Green Tea

Clinical Studies. Several large case-control and cohort studies have mainly focused on the prevention of gastrointestinal and breast cancers with green tea (Camellia sinensis). Results are variable, with some suggesting chronic tea consumption may decrease cancer risk and others reporting no benefits.178–187 Overall, the epidemiologic evidence suggests that green tea consumption may protect against cancer; however, these studies have been mostly observational, and other lifestyle choices of tea drinkers may confound these results. A few studies of green tea have shown some clinical benefits. A decreased occurrence of prostate cancer was reported among healthy men treated with green tea extract (GTE) versus placebo in a recent randomized, placebo-controlled study in 60 volunteers with high-grade prostate intraepithelial neoplasia.190 The study reported a reduction in tumor development (9 of 30 versus 1 of 30) after 1 year of therapy compared to placebo. GTE has also been evaluated to treat premalignant oral lesions. Patients were randomized to three doses of GTE or placebo for 12 weeks. The two higher dose levels were associated with a higher response rate.178 In a breast cancer study, green tea ingestion was associated with improved prognosis in stage I and II cancers, but no effect was seen on grade III cancers.183 Additional human research is needed before a recommendation can be made for or against the use of green tea in cancer prevention or treatment.

Safety. Studies of the specific side effects of green tea are limited. However, green tea, a source of caffeine, is known to act as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant and diuretic; it may also increase the production of stomach acid, worsen ulcer symptoms, increase heart rate, and raise blood pressure. One cup of green tea contains approximately 30 to 50 mg of caffeine, and excessive tea consumption may lead to adverse effects or toxicity. Green tea supplement capsules usually contain less caffeine (approximately 5 mg of caffeine per 500 mg extract).

Lycopene

Lycopene is a carotenoid present in human serum, the liver, adrenal glands, lungs, prostate, colon, and skin at higher levels than other carotenoids. Most dietary lycopene is derived from tomatoes and tomato-based products. Lycopene is also present in many other fruits and plant products, including apricots, pink grapefruit, guava, rose hip, palm oil, and watermelon. Antioxidant and antiproliferative properties have been reported in preclinical research, and there are more than 75 case-control or cohort studies of the association between increased tomato/tomato-based product intake or serum lycopene levels with cancer risk. Approximately two-thirds of these studies suggest benefits in the range of 40% risk reduction, although fewer than half of the studies are statistically significant, and numerous studies provide negative results.191 A study that evaluated the association between intake of lycopene and specific tomato products and prostate cancer risk among 29,361 men during an average of 4.2 years of follow-up reported that lycopene intake was associated with a reduction of prostate cancer risk among men with a family history of prostate cancer, but not in the male population overall.192

Maitake

Clinical Studies. In a small 2002 case series, therapy with Maitake (Grifola frondosa) powder and a proprietary Maitake extract (MD fraction) was associated with tumor regression in greater than 50% of patients with stages II to IV breast, lung, and liver cancer, whereas no improvements were observed in leukemia, gastric cancer, or brain tumors.193 This series had limited information, particularly regarding patient baseline characteristics. A recent report from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center found that Maitake mushrooms had a mixed response on a profile of immune cells; thus, the belief that these mushrooms are purely immunostimulatory is likely incorrect.194

Safety. Although Maitake has not been well studied, a long history of dietary use suggests that it is safe in low doses. Possible adverse effects of concentrated extracts, based on animal research, include hypoglycemia and hypotension. It is not clear if this agent interacts with chemotherapy regimens.

Milk Thistle

Clinical Studies. One randomized clinical trial in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia found a lower incidence of liver toxicity among children randomized to milk thistle (Silybum marianum) therapy.195 Several other trials have evaluated milk thistle, but in combination with several other herbs or supplements; therefore, further study using milk thistle alone is needed before it can be recommended as an anticancer treatment.

Safety. Milk thistle has been investigated for anticancer effects in preclinical and clinical trials; the pharmacokinetics and its mechanisms, effectiveness, and adverse effects reported to date have been reviewed.196 In clinical trials and traditional use, oral milk thistle has generally been reported as well tolerated in recommended doses for up to 6 years of use. Several studies report mild gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, heartburn, diarrhea, epigastric pain, abdominal discomfort, dyspepsia, flatulence, and loss of appetite. Urticaria, eczema, and headache have also been reported. Hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions have been associated with milk thistle ingestion in case reports. Because many patients in available clinical trials have liver conditions, it is unclear whether adverse effects are caused by milk thistle or by the underlying liver condition; the rates of adverse effects are often similar to placebo. Data from in vivo and in vitro studies suggest the inhibition of cytochrome p-450 (CPY450) 3A4 and 2C9 to varying levels.

Mistletoe

Clinical Studies. Multiple case series, retrospective analyses, and prospective trials of mistletoe (Viscum album, Iscador) extracts in humans have been published; these studies were largely conducted in Europe and have examined patients with breast, lung, cervical, colorectal, gastric, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers, as well as renal cell carcinoma and glioma. A 1994 systematic review included 11 controlled clinical trials, not all randomized, and concluded that overall methodologic quality of studies was poor and results were indeterminate.197 Subsequent publications have not provided definitive evidence of efficacy but have suggested survival advantages in patients with colorectal, gastric, or breast cancers.198–200 Negative results have been reported in patients with melanoma.201 According to a 2006 reanalysis of previously published nonrandomized studies on mistletoe therapy, breast cancer patients showed increased survival; however, this required a further evaluation in a well-designed randomized controlled trial.202 In another randomized trial of mistletoe, researchers evaluated the potential side effects from chemotherapy among breast cancer patients and concluded that patients randomized to mistletoe reported fewer side effects. No long-term evaluation was performed to explore the impact on efficacy of treatment.203

Safety. Mistletoe is contraindicated in patients with protein hypersensitivity or chronic progressive infections (e.g., tuberculosis). The most common reactions are erythema and hyperemia.197 Other possible side effects include anorexia, general malaise, depressive moods, fever, local skin inflammation or pain at injection site, mydriasis and miosis/myalgia, and elevated liver enzymes.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Clinical Studies. Several population (epidemiologic) studies report that dietary omega-3 fatty acids (alpha-linolenic acid) or fish oil may reduce the risk of developing breast, colon, or prostate cancer.204–210 There is evidence from epidemiologic studies and randomized controlled trials that an intake of recommended amounts of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in the form of dietary fish or fish oil supplements lowers triglycerides and reduces the risk of death from cardiovascular disease. Two randomized controlled trials report no significant benefits of supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids or fish oil in cancer patients with cachexia.211,212 Questions have been raised, however, about the proportion of DHA to EPA used in these trials. An ongoing National Cancer Institute (NCI)–sponsored clinical trial is examining the effects of fish oil alone or in combination with vitamin D3 in cancer prevention.

Safety. The FDA classifies intake of up to 3 g per day of omega-3 fatty acids from fish as “generally recognized as safe.” Caution may be warranted in diabetic patients (due to potential hyperglycemic effects), patients at risk of bleeding, or those with low blood pressure or high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels.213 DHA may have greater effects than EPA.

An increased risk of bleeding is one of the primary concerns with fish oil supplementation.213 Diets containing salmon oil, mackerel, or cod liver oil have been reported to prolong bleeding times significantly in healthy volunteers. However, in other studies of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, no adverse effects on bleeding time have been observed. Increased bleeding time is suggested to result from either less thromboxane or higher prostacyclin levels. It is unclear if omega-3 fatty acids affect coagulation. Anecdotal evidence suggests that fish oil may increase the international normalized ratio (INR), a measure of bleeding time. However, clinical evidence suggests that fish oil does not affect coagulation, even when taken with anticoagulant therapy. Nevertheless, caution is warranted when omega-3 fatty acids (from plants or fish) are taken with anticoagulant agents. Some species of fish carry a higher risk of environmental contaminants, such as with methylmercury or other heavy metals.

Reishi

Clinical Studies. Treatment with reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) mushroom extract (GanoPoly) for 12 weeks resulted in a significant increase in plasma levels of interleukin 2 (IL-2), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ), decreased IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) levels, and increased natural killer (NK) cells in advanced-stage cancer patients.214,215 Well-designed, long-term studies are needed to confirm these results and to examine potential side effects.

Safety. Caution is recommended when reishi is used in patients with bleeding disorders/coagulopathies or in those taking anticoagulants, as reishi mushroom may alter platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time.216 Caution is also advised in patients with low blood pressure, diabetes, or in those taking antidiabetic agents or antihypertensives.

Resveratrol

Clinical Studies. Resveratrol is a naturally occurring hydroxystilbene identified in more than 70 plant species, including nuts, grapes, pine trees, and certain vines, as well as in red wine. Although there are several observational studies that correlate the consumption of wine with a decrease in cancer or cardiovascular disease risk,217,218 high-quality human trials supporting the efficacy of resveratrol for any indication are currently lacking in the available literature. Ongoing research is examining resveratrol and a possible role in increasing longevity and how it interacts with sirtuins.

Safety. Laboratory study suggests that resveratrol has antiaggregating and antithrombin activity, and may have additive effects when taken with other agents with the same actions219; thus, use of resveratrol with antiplatelets could cause increased risk of bleeding, although clinical reports of drug interactions are lacking. Resveratrol apparently has the potential to act as an estrogen agonist or antagonist, depending on such factors as cell type and estrogen receptor isoform (ER-α or ER-β).220–222 Resveratrol has also been shown to inhibit vitamin D3 receptor expression through estrogenic regulation.223 Clinical evidence of estrogen interactions is lacking. Some in vitro and in vivo studies suggest that resveratrol might interfere with paclitaxel.224 Resveratrol inhibited all of the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) tested (1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 2A6, 2B6, 2E1, 3A4, 4A), except for 2E1.225

Selenium

Clinical Studies. Initial evidence has suggested that selenium supplementation reduces the risk of developing prostate cancer in men with normal baseline prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels and low selenium blood levels. This is the subject of large, well-designed studies, including the Nutritional Prevention of Cancer (NPC) trial and the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT),226–240 as well as prior population and case-control studies.241,242

The NPC trial with 1,312 Americans reported that 200 mg of daily selenium reduces the overall incidence of prostate cancer, although these protective effects only occurred in men with baseline PSA levels less than or equal to 4 ng per milliliter and those with low baseline blood selenium levels (less than 123.2 ng per milliliter).229–231,243 The NPC trial was primarily designed to measure the development of nonmelanoma skin cancers and not other types of cancers; therefore, these prostate cancer results cannot be considered definitive.

SELECT was started in 2001 with 32,400 men with serum PSA levels less than or equal to 4 ng per milliliter. The study was ended early due to an interim analysis that determined that the study could not meet its expected end point of a 25% reduction in prostate cancer. Subset analyses indicated selenium supplementation was associated with increased development of diabetes mellitus.

Safety. The level of selenium exposure that will cause chronic toxicity is not clear. Selenium toxicity may cause gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, garlic-like breath odor, and metallic taste), neuromuscular–psychiatric disturbances (weakness/fatigue, lightheadedness, irritability, hyperreflexia, muscle tenderness, tremor, and peripheral neuropathy), dermatologic changes (skin rash/dermatitis/flushing, fingernail loss/thickening/blotching/streaking/paronychia, and hair changes/loss), liver dysfunction, kidney dysfunction, thrombocytopenia (low blood platelets), immune alterations (NK cell impairment), thyroid dysfunction (decreased T3), reduced sperm motility, or growth retardation.

Soy

Clinical Studies. Preliminary research using soy (Glycine max) to control hot flashes in women with breast cancer suggests that it is possibly safe,244 although the pending results of ongoing research in this area may provide more definitive safety data. Recent studies have indicated that moderate dietary soy intake (observed in most traditional Asian diets—no more than three servings daily) shows no risk and may have possible benefits to breast cancer patients, even among women with estrogen-positive breast cancers.245,246

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree