PEARLS

❖ Changes in the major structures of the ear establish 3 main types of hearing loss: conductive (which can be reversed), sensorineural (which cannot be reversed), and mixed (which can be partially reversed).

❖ Detecting hearing loss in a physical therapy setting can range from the use of cues to screenings to more formal tests.

❖ Simple interventions, such as changes in the mode of communication and environment (ie, speaking slowly in a noncompeting environment), will enhance communication.

❖ All 5 major senses tend to decline with old age, and yet they are needed to enhance communication; therefore, physical therapists should bring in the other senses as much as possible.

❖ The voice of an older person changes with age because of reduced respiratory efficiency and changes in the oral and laryngeal cavities. Nevertheless, these changes have little impact on the older person’s ability to communicate.

❖ Accuracy, completeness, timeliness, and honesty are the keys to effective note writing.

❖ To motivate older persons, the therapist must first assess the person’s internal motivation (ie, values and experience) and then assess and appropriately modify the external factors of motivation (ie, the physical and social environment).

A patient gets better, a child graduates from college, a pain is felt, and a new idea comes to mind; yet, this information is unable to be communicated. Why? Is it old age? Is it because the recipients of the information do not understand? Is there some pathological process that is going on that is impairing the communication process?

This chapter discusses ways that communication may be different with age. The first section explores the older individual in terms of normal and pathological changes with age that impact communication. A special section discusses the ethnic influences on aging and communication. Impediments and enhancements to communication with the health professional are also examined. The final sections of this chapter explore writing skills and the important topic of compliance and motivation.

CHANGES WITH AGE AFFECTING COMMUNICATION

Hearing

Normal Changes Affecting Hearing

Hearing loss is third only to arthritis and hypertension as the most common physical complaint of older adults.1 Statistics show that between 25% and 40% of persons over the age of 65 suffer from hearing loss.1 In addition, with each consecutive decade after 70 years, the prevalence of those affected increases dramatically.1

Changes in the major structures of the ear establish the 3 main types of hearing loss: conductive, sensorineural, and mixed. Conductive hearing loss is a result of changes in the outer or middle ear that blocks the acoustic energy. The changes in the external and middle ear follow.

Changes in the external ear include the following:

❖ Decreased sensation that causes the patient to be unaware of a buildup of wax

❖ Excess hair growth in the outer ear, especially in men, that can aid in the accumulation of wax

❖ A decrease in the wax-producing glands and a subsequent tendency for the wax to become drier

Changes in the middle ear are as follows:

❖ The tympanic membrane becomes more rigid and translucent with age

❖ Negative pressure in the middle ear as a result of a decrease in the elasticity and displacement of tissue in the nasopharynx causing the eustachian tube to resist opening

Sensorineural hearing loss occurs because of changes in the inner ear. Changes in the inner ear include the following:

❖ Death of hair cells in the cochlea

❖ Damage to the basilar membrane within the cochlea2

Mixed disorders are a combination of sensorineural and conductive. In general, conductive hearing disorders may be reversed, sensorineural disorders cannot be reversed, and mixed disorders can be partially reversed.

A common term used to describe the hearing loss of old age is presbycusis. This general type of hearing loss is sensorineural and, therefore, not reversible. The characteristics of presbycusis are as follows3:

❖ A reduced sensitivity to high-pitched sounds, such as sh, s, t, z, v, f, ch, and g, occurs

❖ Bilaterally the hearing loss is equal

❖ Men are more affected than women

❖ A decreased hearing of pure tones occurs

The hearing loss often associated with old age is usually insidious. It gradually appears, and often patients do not realize that they are misinterpreting communications. For example, when an older person with presbycusis is asked, “How old are you?” The answer may be “fine.” This inappropriate response may lead to frustration on the part of the patient, family, and health professional. In addition, the older person with hearing loss may feel depressed, isolated, and angry.4

Pathological Changes Affecting Hearing

The classification, manifestation, and approach to the pathological changes with age affecting hearing are similar to the normal changes already listed. In conductive hearing loss, some of the common causes might be infection and osteosclerosis.2 In the area of sensorineural changes, some causes may be drug toxicity, brain tumor, or Ménière disease.2 Finally, in mixed disorders, a foreign body or an infection can cause the problem.

Evaluation

For both normal and pathological changes in hearing with aging, thorough screening is imperative to delineate the cause and type of hearing loss. Table 16-1 lists several signs of hearing impairment.

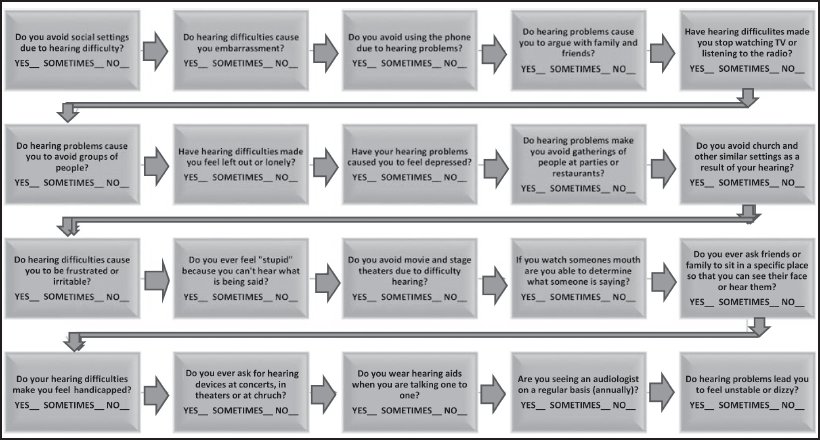

In addition, once a person is suspected of having a hearing loss, the Hearing Question Flow Path can be administered. This test evaluates the person’s response to the hearing loss emotionally and socially. It is helpful in establishing a clear way to determine the handicap that may be imposed by poor hearing in the therapeutic setting as well as at home and in the community. Figure 16-1 is a sample hearing question flowchart that the authors use when hearing presents a communication problem.

After the hearing-impaired person completes this test, the caregiver totals the numeric value of the responses for a total score and 2 subscores delineating values for the emotional and social/situational areas. Patients who avoid social encounters and are becoming emotionally isolated are identified by a high “S” score value. Persons whose emotional supports are weak would score high points in the “E” category.

A rough estimate of total scores is as follows2:

❖ 0 to 16: The individual does not have a perceived handicap due to hearing loss. This person either has little objective hearing loss or enjoys adequate coping skills.

❖ 17 to 42: The person has a mild to moderate self-perceived handicap. This person requires evaluation for other stressors and may need help with realistic goal setting, defining needs, and following through with care.

❖ 43+: The person’s coping skills are extremely limited. This person requires concrete direction in terms of self-care and seeking proper assistance for the hearing loss.

Interventions

Interventions for hearing loss range from specific rehabilitation programs to appropriate assistive devices (ie, hearing aids). In addition, the health team can keep in mind measures and aids to communication (Tables 16-2 and 16-3).

Vision and the Other Senses

Hearing obviously impacts communication. Nevertheless, changes in the other senses also impact communication. The major but normal change with age in vision called presbyopia begins as early as the fourth decade. (For specific information on presbyopia and vision changes, see Chapter 3.) Most vision deficits normally caused by aging can be managed by changes in lenses.5 In addition, environmental modifications can enhance communication as well as ensure safety.6

Figure 16-1. The Hearing Question Flow Path for older adults: a helpful and frequently used clinical tool.

The literature also notes a decline in the senses of touch, taste, and smell.7 A lack of information in these areas can alter normal communication. Suggestions for health professionals in this area are the following:

❖ Try to use touch as much as possible to enhance communications.

❖ Bring in the other senses as much as possible. For example, describe the smell of the bread the patient is making or the roses he or she just received.

❖ Instruct the family or staff in methods of seasoning food to enhance the sense of taste (ie, different healthy seasonings).

❖ Make a mental checklist to include the other senses in a treatment session (eg, show the patient the menu for the day and discuss the taste and smell of the food).

Voice

A person’s ability to vocalize is another important variable in communication. Studies on voice cues alone have shown that older speakers tend to be negatively rated compared to younger speakers.8,9 There are normal changes that occur with age in the voices of men and women; however, they do not cause significant problems with communication. Men, according to Remarcle et al,10 experience a higher fundamental frequency due to vocal fold atrophy. On the other hand, women experience a lower frequency due to a slight hoarseness and vocal fold edema.

Normal aging changes can affect voice production. The changes with age in the human body that can affect speech are as follows:

- Reduced respiratory efficiency caused by:

a. Degeneration of vertebral discs (senile kyphosis)11

b. Decreased elasticity of the rib cartilages as well as ossification and calcification of these cartilages12

c. Reduced recoil and elasticity of the lungs13 resulting in lower frequencies, decreased loudness, and shortening of the length of utterances per breath14

- Changes in the oral cavity caused by:

a. Changes in the structure of the lower jaw

b. Loss of dentition

c. Weakening and loss of sensitivity of the pharyngeal muscles

d. Reduced activity of the salivary glands15

e. Atrophy of the lips and tongue16 resulting in an alteration in resonance, increased nasality, and reduced articulatory accuracy

- Changes in the laryngeal cavity caused by:

a. The laryngeal cartilages undergoing ossification and calcification

b. Drying out of the laryngeal mucosa

c. Reduced vascular supply to the mucosa

d. Progressive thinning and shortening of the vocal folds resulting in vocal tremors, roughness, breathiness, and hoarseness17

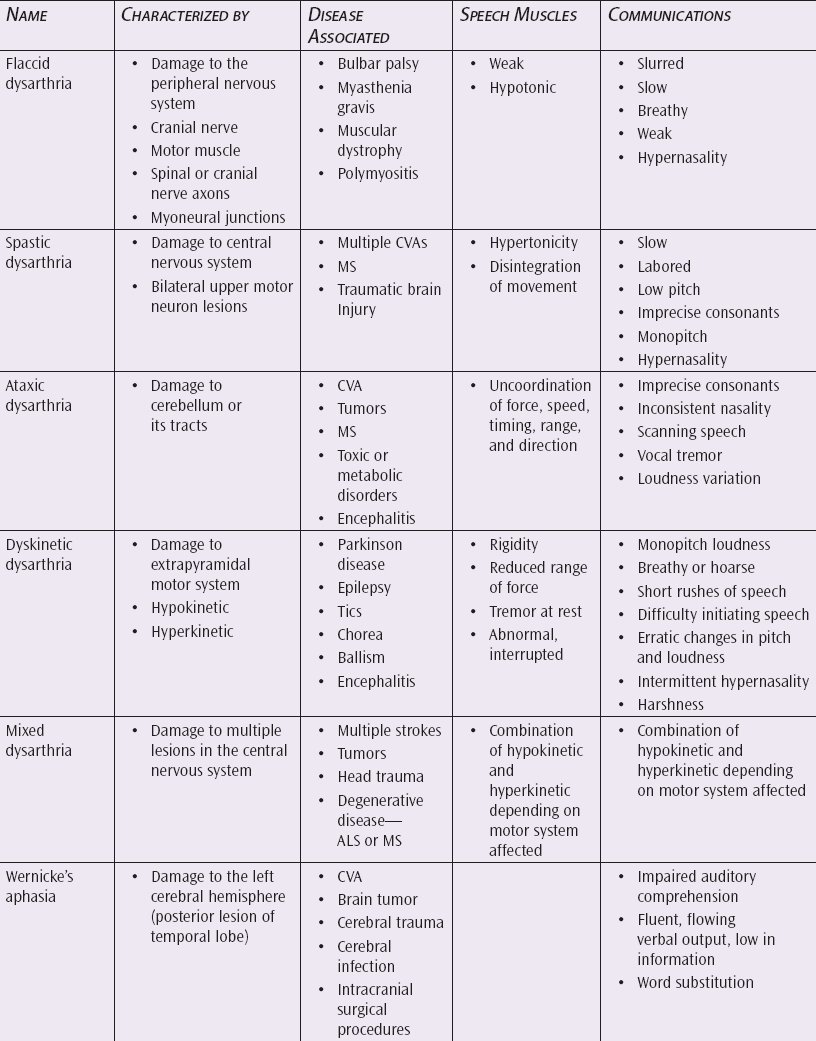

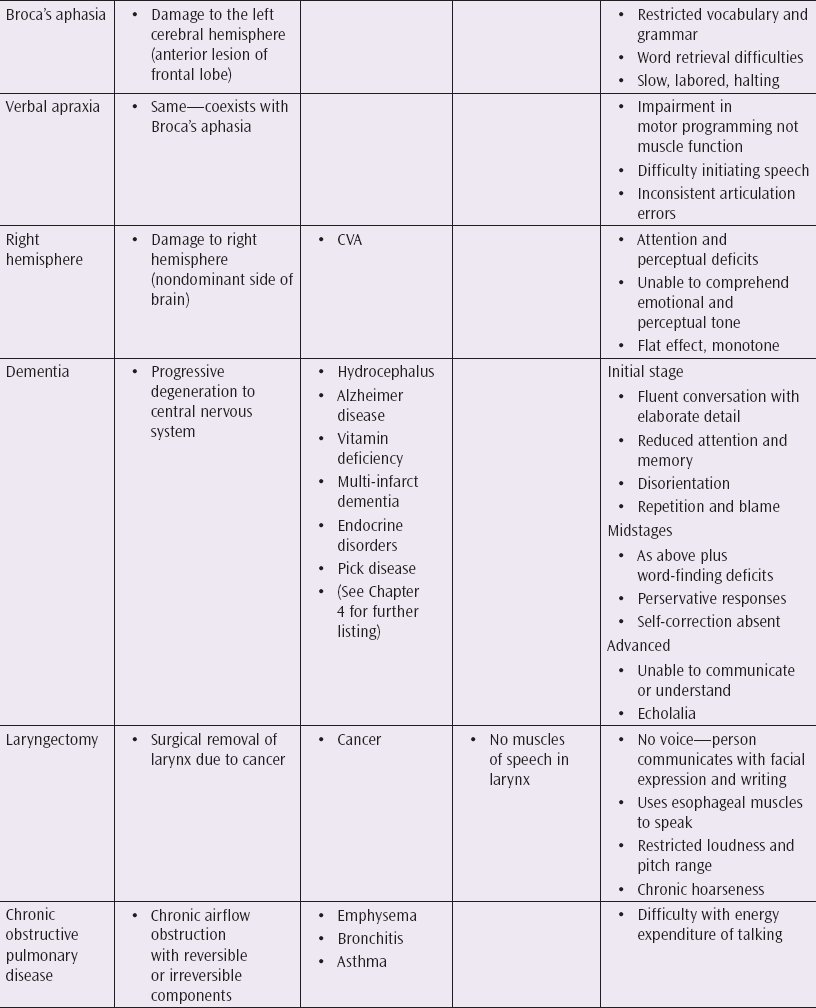

As mentioned earlier, the changes listed essentially have minimal effect on communication; however, pathological causes, such as dysarthria, apraxia, aphasia, dementia, laryngectomy, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, can cause significant impairment in communication (Table 16-4).

Evaluation of pathologies of the voice should be performed by a trained speech and language professional. However, the treatment cannot be done solely by these professionals. To maximize the benefits of treatment, the family, staff, and rehabilitation team must become involved. Table 16-5 provides a list of strategies for improving communication for the various pathologies already noted.3

Ethnicity

How can a person’s origins, rules, and contrasts affect communication between the person, family, and health professional? Is cultural diversity a major concern when looking at the demographics in the United States? In the year 2000, an estimated 30% of the population was Asian, Hispanic, Native American, and black.18 Often, people tend to overgeneralize or overemphasize cultural differences and therefore miscommunicate.19

So how does one work most effectively with cultural differences? Like other areas of human intervention, the therapist must make an appropriate evaluation of the situation. Table 16-6 provides examples of assessment categories.20

The therapist should consider this checklist when working with older adults; however, prior to implementing any intervention, the therapist should rank its importance. In a study by Chee and Kane,21 the priority of ethnic factors was addressed. They discovered that Japanese Americans highly rated ethnic factors in a nursing home, such as similar ethnic background of staff, ethnic foods, programming activities, and community involvement.21 The black participants in this study placed more emphasis on access to family than on the ethnic considerations.21

The key to ethnic considerations in communications with older persons is to evaluate effectively the needs of the patient, to become more sensitive to their concerns, and to provide modifications in the environment commensurate with the needs identified.

THE TEAM

Why place the team in the middle of a chapter on communication? There are 3 reasons: first, to explore the method in which the team interacts with itself and its effectiveness in this effort; second, to examine the team or the individual on the team’s ability to communicate with the older patient; and third, to determine the continuity and cohesiveness of care provided by a team approach when compared to other models of intervention.

What is the role of the team in geriatric rehabilitation? There is no definitive answer to this question. In the studies to follow, the team is a constantly changing variable. It can simply be a doctor and a nurse, or it can be expanded to include a social worker, dietitian, occupational therapist, speech-language pathologist, physical therapist, leisure services professional, psychologist, or dentist.22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree