DISEASE BASICS

Infections of the skin can be divided into two clinical categories: infections with pus (purulent) and infections without pus (nonpurulent).

1 Purulent skin infections are associated with drainage of pus and/or abscesses, whereas nonpurulent skin infections have inflamed skin without

pus. These infections are typically caused by bacteria such as staphylococci or streptococci that are present on the skin. Infection occurs when there is a break in the skin that allows bacteria to enter.

2Streptococci are a group of gram-positive bacteria that cause several clinically important illnesses, including skin infections. They are broadly organized into two groups: pyogenic (beta-hemolytic) and alpha-hemolytic. For example, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Strep) is a beta-hemolytic

Streptococcus that commonly causes skin infections and can even cause necrotizing soft-tissue infection. In general, streptococci lead to cellulitis and nonpurulent skin infections.

Staphylococcus aureus is another gram-positive bacterium that commonly causes skin infections.

3 An estimated 30% of humans are colonized with

S. aureus on their skin and in their nostrils.

3,4 However, when the skin or mucosal barriers are disrupted,

S. aureus causes significant infections. Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are strains of

S. aureus that are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics and therefore can be more difficult to treat. In general,

S. aureus—and particularly MRSA—leads to purulent skin infections.

Skin + Pus = MRSA until proven otherwise.

Risk factors for developing a bacterial skin infection include (1) a recent injury to the skin through shaving or a cut, abrasion, or scrape suffered during athletic activities; (2) the presence of a viral or fungal infection such as herpes or athlete’s foot; or (3) chronic skin conditions such as eczema or psoriasis. Bacterial skin infections occur primarily in athletes with prolonged skin-to-skin contact, including wrestlers, rugby, judo, hockey, basketball, and football players. However, these infections can occur even in athletes with no risk factors and among athletes with little skin-to-skin contact.

5 Recurrence of skin infections is common: 22% to 49% of patients with a skin infection report at least one prior episode.

2Risk factors for skin infections? Anything that disrupts the skin barrier.

TYPICAL PRESENTATION

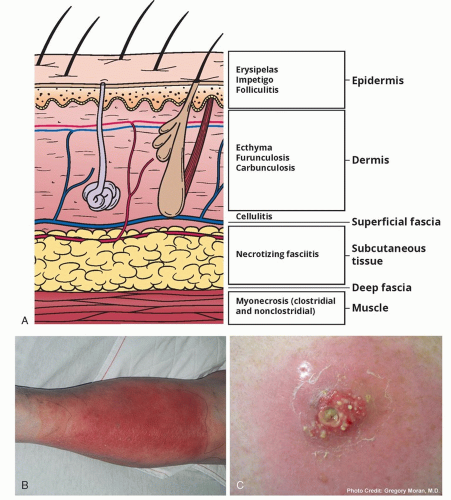

Bacterial skin infections can manifest in several clinical syndromes (

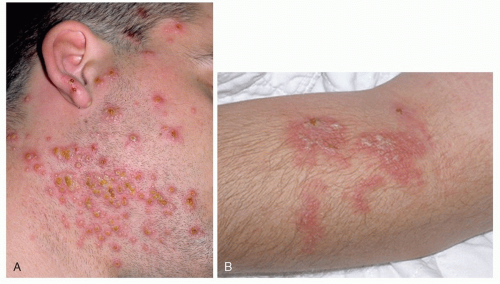

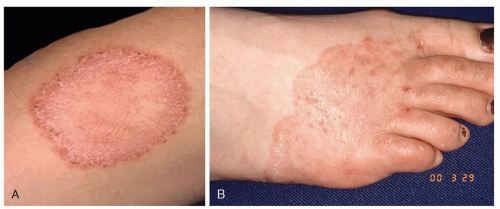

Figure 1.1). One form of skin infection is called impetigo, which is characterized by well-defined, yellow crusted, scaling plaques. Erysipelas is a well-defined, erythematous plaque. Furunculosis occurs when multiple smaller boils (or pockets of pus) in the same area join together to form a large boil. Lastly, folliculitis presents as small pustules around hair follicles.

Pseudomonas folliculitis or “hot tub folliculitis” can also occur in athletes who use hot tubs and whirlpools for rehabilitation.

6 This infection typically presents as pruritic pustules that emerge on the skin that was submerged in the whirlpool. More specifically, the affected area typically involves skin covered by the bathing suit.

6The most common symptom of a bacterial skin infection is a dull ache or pain at the area of involvement. Other symptoms include swelling, warmth, or redness. These symptoms typically worsen with the redness spreading over a period of hours to days. The onset of skin infections can be gradual or sudden. Itching is not a common symptom. Fever and chills can accompany bacterial skin infections but are not always present. That is, bacterial skin infections may occur in the absence of fever.

TRANSMISSION

S. aureus can spread through contact with pus or drainage from an infected wound, skin-to-skin contact with an infected person, or indirectly through a contaminated environment. These routes of transmission are common in the athletic setting due to the number of athletes

sharing the training facility and frequent, close interaction. Outbreaks of

S. aureus skin infections have occurred in football, wresting, rugby, and basketball athletes, among others.

7,8,9,10 In one outbreak among fencers, sharing of equipment was linked to transmission of MRSA.

8

PREVENTION MEASURES

Treatment typically includes antibiotic therapy and drainage of pus if present (typically via an incision and drainage or “I&D”). Skin lesions should be properly covered until they are healed.

Implementing therapy, covering the infection, and promptly removing infected athletes from contact with other athletes (ie, “isolation”) can help decrease the number of missed practices and risk of transmission.

5If pus is present, it needs to be drained.

In general, athletes should not share equipment or personal items such as towels, razors, knee/elbow pads, or other athletic gear.

11 Athletes with skin infections should also avoid common areas (eg, weight rooms) and the hydrotherapy pools until the infection is controlled and can be covered. If the infected area cannot be covered, athletes should not participate in team activities such as practice and competition until the lesions heal.

For the prevention of

Pseudomonas folliculitis, athletic trainers should ensure adequate chlorine levels and proper pH (7.0-7.4) in pools and whirlpools.

5 In addition, if trainers suspect that a pool has been exposed to an infected athlete, the pool should be drained and cleaned.

5 See Chapter 4 for more details about routine maintenance of hydrotherapy pools.