FIGURE 25.1 MRCP demonstrating CBD stones.

Endoscopic Ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a semi-invasive test that can be performed with a very low rate of complications (<0.1%). The sensitivity (92% to 100%) and specificity (95% to 100%) for the diagnosis of CBD stones by EUS are excellent. The negative predictive value for EUS is more than 97%. Therefore, when EUS is negative for common duct stones, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) can be avoided.

Direct Cholangiography

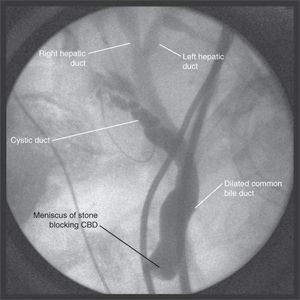

Direct cholangiography is the gold standard for diagnosing CBD stones. Both endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) techniques can be used to directly visualize the biliary tree. In addition to identifying CBD stones, endoscopic cholangiography (Fig. 25.2) permits safe removal of most stones and is therefore the preferred approach for patients with suspected CBD stones. Skilled endoscopists can successfully cannulate the CBD in 90% to 95% of patients. Complications of diagnostic cholangiography including pancreatitis and cholangitis occur in approximately 5% of patients; the vast majority of these complications are mild and self-limiting. ERC may be unsuccessful in patients with previous gastric surgery (Billroth II reconstruction, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass), periampullary diverticula, or tortuous bile ducts. PTC may be used to image the bile ducts if ERC is unsuccessful.

FIGURE 25.2 ERCP demonstrating CBD stones.

Intraoperative Cholangiography

IOC also can be successfully accomplished in more than 95% of cases. The cholangiogram should be carefully evaluated for filling defects within the ducts, presence of contrast in the duodenum, and the intrahepatic biliary anatomy (Fig. 25.3). Importantly, the surgeon must be able to interpret IOC images in real time, in the operating room for this study to be valuable. Debate continues over the need to perform routine IOC at the time of cholecystectomy. Advocates of routine IOC argue that asymptomatic CBD stones can be identified and biliary injuries prevented by performing routine IOC. Critics of this approach suggest that the incidence of retained stones is no greater when cholangiography is performed selectively based on clinical and laboratory criteria. The indications for performing cholangiography during cholecystectomy include (a) a dilated CBD, (b) a wide cystic duct, (c) palpable CBD stones, (d) elevated serum liver function tests or bilirubin, and (e) a history of pancreatitis. If these criteria are strictly followed, approximately 30% of patients will require IOC at the time of cholecystectomy. In addition to defining biliary anatomy, IOC can identify the size, number, and location of CBD stones. This information is critical in choosing the most appropriate treatment for CBD stones.

FIGURE 25.3 Intraoperative cholangiogram. (From Lillemoe K, Jarnigan W. Master techniques in surgery: hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.)

Intraoperative Ultrasonography

Intraoperative ultrasonography also can be used to identify CBD stones at the time of cholecystectomy. In experienced hands, intraoperative ultrasonography has been shown to be comparable to IOC for the diagnosis of CBD stones. Laparoscopic ultrasonography is performed with a high-frequency (7.5- to 10-mHz) probe, and the bile duct is imaged in the transverse and longitudinal planes. The distal bile duct can be visualized in more than 95% of cases.

General Diagnostic Strategy

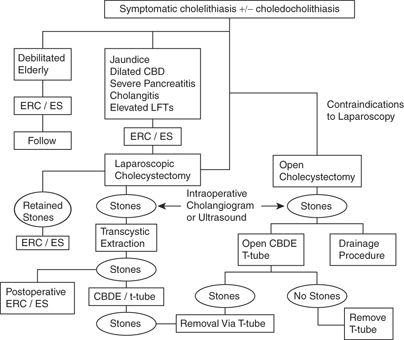

The choice of radiologic studies used to evaluate a patient with suspected choledocholithiasis should be based on the probability of this diagnosis. A simple algorithm for the workup of patients with CBD stones is shown in Figure 25.4. Patients at highest risk for choledocholithiasis should undergo endoscopic cholangiography. Patients at intermediate risk may be screened with magnetic resonance cholangiography or EUS and proceed to laparoscopic cholecystectomy if no stones are identified. Those patients at low risk of harboring common duct stones may be evaluated with IOC at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with laparoscopic CBD exploration or postoperative endoscopic stone extraction reserved for the few patients with a positive study.

FIGURE 25.4 Algorithm for the management of CBD stones. (From Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, et al. Greenfield’s surgery: scientific principles & practice, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.)

MANAGEMENT

Currently, several options are available to the surgeon for the treatment of CBD stones. In choosing the most appropriate approach for an individual patient, factors such as the local endoscopic expertise, the surgeon’s laparoscopic skill, and the patient’s clinical condition must be considered.

ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

ERC with endoscopic sphincterotomy permits CBD stones to be removed without the need for conventional surgery. Stones can be successfully removed from the CBD in 85% to 95% of cases. The endoscopic approach is particularly useful for patients prior to cholecystectomy in whom a high suspicion exists for CBD calculi, particularly if laparoscopic CBD exploration is not available. Endoscopic clearance of stones from the CBD precholecystectomy can obviate the need for an open operation. Furthermore, if endoscopic stone extraction is not possible because of multiple gallstones, intrahepatic stones, large gallstones, impacted stones, duodenal diverticula, prior gastrectomy, or bile duct stricture, this information is known preoperatively, and an open CBD exploration or drainage procedure can be performed at the time of cholecystectomy. After sphincterotomy, most stones smaller than 1 cm in diameter pass spontaneously. A balloon catheter or stone basket also can be used to retrieve stones if needed. If endoscopic clearance is incomplete, an endoscopic stent can be placed into the CBD to maintain drainage and prevent cholangitis.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction is well tolerated in most patients. Complications occur in 5% to 8% of patients and include cholangitis, pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding. The overall mortality rate is 0.2% to 0.5%. Complete clearance of all common duct stones is achieved endoscopically in 71% to 75% of patients at the first procedure and in 84% to 95% of patients after multiple endoscopic procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree