Category

Details

Identifying information/demographics

Date of procedure

Name of patient

Unique patient identifying number (e.g., national ID number, medical record number)

Lesion details

Anatomic location of lesion

Size of lesion

Dermatological description of lesion type (e.g., macule, papule, plaque)

Whether lesion is solitary or representative sample of multiple lesions

Biopsy technique

Excisional or incisional biopsy

If excisional – technique used if other than elliptical excision (e.g., saucerization with intent for complete removal of lesion)

If incisional – technique used (e.g., shave biopsy, punch biopsy), extent of the biopsy relative to the size of lesion (e.g., small 3 mm shave sample from a large 3 cm plaque)

Diagnosis

Most probable clinical diagnosis

Differential diagnoses, if applicable

Requests for nonroutine processing

Request for special stains

Addition helpful details

Patient history (e.g., history of melanoma)

Lesion history (e.g., rapid change, presence of ulceration, recurrence at previous biopsy site)

Annotation of suspicious foci within lesion (using drawing or photograph of lesion)

Biopsy

The clinician selects the biopsy technique [4]. According to the American Academy of Derma tology guidelines for the diagnosis of melanoma, “Whenever possible, excise the lesion for diagnostic purposes using narrow margins” [5]. Excision is defined as complete removal of a skin lesion for the purpose of performing histopathological examination; the most common technique used is elliptical excision. Excision offers advantages for pathological diagnosis. The whole lesion is submitted to the pathology laboratory for analysis so the chance of sampling error is reduced; melanoma staging is more accurate since the lesion is not truncated at the base; primary removal of the lesion is achieved, so recurrence of skin cancer is less likely even in the case of melanoma erroneously diagnosed as a nevus; finally, correct orientation of the lesion for processing at the pathology laboratory is straightforward.

When performing an incisional biopsy such as shave or punch biopsy, a sample from a skin lesion is obtained for histopathologic examination, without an explicit intent of completely removing the lesion. With regard to indication for incisional biopsy, the American Academy of Dermatology notes: “An incisional biopsy technique is appropriate when the suspicion for melanoma is low, when the lesion is large, or when it is impractical to perform an excision” [5]. The aim in these cases is to establish the diagnosis and plan, if necessary, more definitive therapy. The appeal of incisional biopsy for clinicians is that it is technically simpler and faster than excision, usually leaves smaller scars, and, in the case of shave biopsy, does not require a sterile technique and does not require stitch removal.

However, incisional biopsy can limit the extent of pathological diagnosis. First, with a shave technique, the lesion can be transected at the base, making it difficult for a pathologist to differentiate a solar keratosis from a superficial squamous cell carcinoma or causing an underestimation of the Breslow thickness in melanoma. In fact, Ng et al. reported that shave and punch biopsies underestimate the final Breslow depth of melanoma by approximately 8 and 20 %, respectively [6]. Second, a diagnostic error is more likely to occur with incisional biopsy due to the limited sampling of the lesion [7, 8]. Finally, in case of diagnostic error associated with an incisional biopsy of skin cancer, there is a greater chance of adverse event due to progression of the residual cancer [7].

Pathology Laboratory Processing

Briefly, the formalin-fixated biopsy specimen is processed at the pathology laboratory as follows: the biopsied specimen is often further sectioned into smaller pieces (e.g., “bread-loafing” of excisional specimen); each piece is put into a cassette and embedded in paraffin, resulting in paraffin blocks; each paraffin block is trimmed until the edge is straight, and then thinly sectioned samples of tissue are mounted on a glass slide; the slide specimens are stained with hematoxylin and eosin. It has been estimated that the glass-mounted specimens available for the pathologist’s analysis represent a mere 2 % of the lesion [3].

As previously noted, the separation between clinical examination of the lesion and the processing at pathology laboratory can entail some limitations. First, the sampling technique at the laboratory grossing bench is often not related to clinical or dermoscopic features of the lesion. Second, tissue is discarded during processing at the pathology laboratory. The concern is that the laboratory sampling of the tissue will be somewhat random and fail to provide the pathologist with the areas that were most concerning to the clinician. To this end, different techniques have been suggested to alert the grossing pathologist to clinically suspicious foci, including annotations of the specimen with dye, stitch, or superficial scoring, adding an annotated photograph of the lesion with the requisition slip and using ex vivo dermoscopy at the grossing bench [9, 10].

Microscopic Analysis

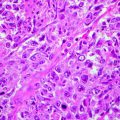

The pathologist analyzes the slide specimen and renders a diagnosis which is communicated to the clinician. It is imperative for clinicians to understand that pathology is another form of morphological diagnosis with accuracy less than 100 %. Like any type of diagnosis, it is subjective and error-prone. The more information the pathologist receives about the patient and lesion, the better the sampling of lesion at the bedside and pathology laboratory; the more the pathologist is trained and experienced with dermatopathology, the greater the chance of accurate diagnosis.

There are several pitfalls in pathological diagnosis of skin cancer that can be mended by better clinical-pathological communication [11]. Some examples follow.

First, histopathological diagnosis of melanoma in situ on sun-damaged skin, also termed lentigo maligna, can be challenging. The early signs of melanoma – proliferation of solitary melanocytes along the basal layer of the epidermis, small nest formation, and slight extension down to infundibula, in association with solar elastosis in the dermis – can be quite subtle. In particular, if the pathologist receives a 3 mm section of tissue with such subtle changes and is not made aware that this section is a small incisional sample of a 2-cm pigmented patch on the face of an elderly individual, the pathologist may be inclined to diagnose the lesion as a junctional nevus. Pathologists may assume that the biopsy specimen represents the size of most or the entire clinical lesion; the apparent small size of biopsy specimen may tilt diagnosis toward benign. In addition, the area sampled may not be the “worst” or most diagnostic area on histopathology. For example, Somach el al. showed that 40 % of excisions of lentigo maligna demonstrated more pronounced histopathologic features of melanoma than previous incisions of the same lesions [8]. The knowledge that the lesion is a large pigmented patch on sun-damaged face of an elderly individual, clinically unlikely to be a junctional nevus, will likely raise the pathologist’s suspicion that the lesion may represent a melanoma in situ. In case of doubt, the pathologist may request the clinician for further, larger sampling of the lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree