Circumscribed Masses

Masses with circumscribed margins are a common finding on mammography. Well-defined lesions are more commonly benign, but it imperative that the radiologist evaluating a mass differentiate those that are characteristically benign from the indeterminate or suspicious lesions. Careful mammographic assessment includes comparison with prior mammography and the use of spot compression to assess the details of the margin of a seemingly circumscribed mass. Sonography (1) plays a key role in the differentiation of solid from cystic masses and greatly facilitates the recommendations for follow-up or further evaluation of the patient.

Assessment of Circumscribed Masses

An approach to the evaluation of a well-defined mass on mammography includes an assessment of the shape, density, margins, size, orientation, presence of a fatty halo, and presence of other findings (i.e., calcifications). Benign lesions tend to be isodense or less dense than the parenchyma and to have very circumscribed margins, whereas malignant masses are more often of greater density and have fine irregularity or micronodularity on their borders.

The shapes of masses that are circumscribed may be round, oval, or lobular. The margination that is described as “circumscribed” allows one to visualize a fine, clear edge around the entire mass. Often masses that are circumscribed may be overlapped by parenchyma in some areas. These are described as obscured or partially circumscribed. A microlobulated margin appears as fine nodularity or undulation of the edge of the lesion and implies a more malignant nature.

A basic division of well-circumscribed masses based on their density is of help in determining possible etiologies of and approach to such lesions. In Table 4.1 the differential diagnosis of circumscribed masses based on their density is shown. Masses that are fatty—lipomas, oil cysts, and galactoceles—and circumscribed masses that are mixed density are characteristically benign. Isodense circumscribed masses include benign and malignant lesions, and an evaluation of the borders is critical to help differentiate these etiologies. Masses that are of high density, particularly for their size, are of concern for malignancies. However, in a study of radiologists’ interpretations of mass density, Jackson et al. (2) found that the assessment of mammographic density of masses was quite variable among different readers; in addition, the density assessment was of limited value in the prediction of benign versus malignant for noncalcified breast masses.

The mammographic feature of greatest importance in assessing a relatively circumscribed isodense mass is its margination. Any notching, waviness, or indistinctness of the margins of a mass should be regarded with suspicion (3). The presence of a halo sign, i.e., a fine radiolucent ring surrounding a well-defined mass, has long been considered to be a mammographic sign of benignancy (4). The halo may be due to compression of fat by the mass (5) or to Mach effect (6). Swann et al. (7) have, however, described 25 malignant lesions from approximately 1,000 breast cancers in which a halo sign was present. The presence of a halo suggests but does not guarantee a benign process (7). Certainly, the presence of a partially circumscribed margin and a partially indistinct margin is suspicious, and biopsy is indicated in this situation.

Stability in size from prior mammography is an important factor that suggests that a circumscribed noncystic mass is benign. The growth rates of breast cancers are quite variable. In two series, the mean doubling times for mammary carcinoma have been found to be 212 (8) and 325 (9) days, respectively. The lack of interval change suggests that a well-defined lesion is more likely benign, but this is not confirmatory. Meyer and Kopans (10) reported five cases of occult cancers that did not change in size on follow-up mammography over a minimum of 2 years and a maximum of 4.5 years from the original study. Therefore, if a nodule is followed and there is no interval change in the size at 6 months or 1 year, continued follow-up is necessary. In addition, the other features of density and margination are used to decide whether to follow or biopsy a circumscribed mass.

TABLE 4.1 Differential Diagnosis of Circumscribed Masses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Circumscribed Masses of Fat Density

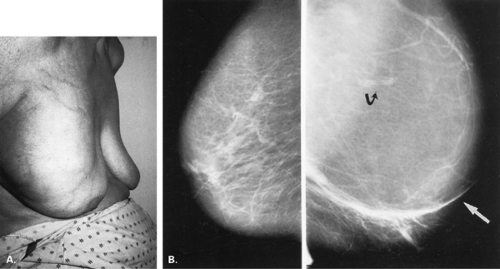

Lipoma

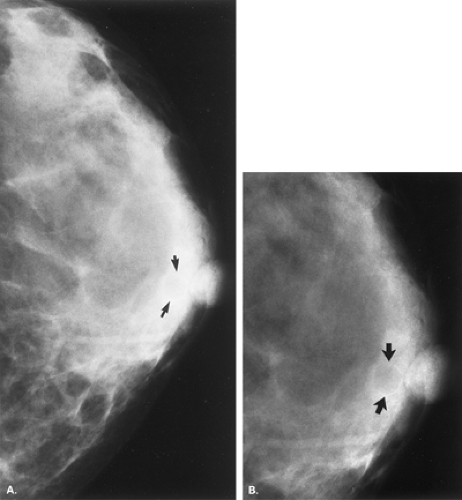

Lipomas are benign, well-circumscribed radiolucent masses (Figs. 4.1,4.2,4.3,4.4,4.5). Clinically, lipomas are either nonpalpable or, if palpable, soft and freely mobile. Lipomas are visualized more easily in an otherwise dense, glandular breast because of the difference in density. In a fatty breast, this radiolucent mass is perceived because it is surrounded by a thin capsule and, if large, displaces the normal breast around it (11). Often lipomas may be located posteriorly at the chest wall and project forward into the breast. Only the anterior aspect of the capsule may be visible on mammography in these cases. Lipomas may develop coarse calcification, probably secondary to infarction (Fig. 4.6). On ultrasound, lipomas are usually intensely hyperechoic, oval, and well defined.

Fat Necrosis

Posttraumatic oil cysts, a form of fat necrosis, may occur as early as 6 months after breast trauma or surgery. Oil cysts may be evident in a pattern corresponding to the path of the seat belt shoulder restraint in patients who have been in automobile accidents (12). Clinically, an area of fat necrosis may be asymptomatic, or it may be an indurated mass with thickening or retraction of the overlying skin. Histologically, the fat necrosis is characterized by anuclear fat cells, histiocytic giant cells, and foamy phagocytic histiocytes. The necrotic focus may cavitate, forming an oil cyst (13), and the wall of the oil cyst may calcify in an eggshell pattern. This ringlike calcification (Figs. 4.7,4.8,4.9,4.10) in the wall of an oil cyst, as originally described by Leborgne (14), is characteristic of this form of fat necrosis. Extensive oil cysts in the subcutaneous area of the breast and the soft tissues elsewhere are seen in the condition known as steatocystoma multiplex (15) (Fig. 4.11).

Galactoceles

Galactoceles may be radiolucent masses or they may be of mixed density or isodense, depending on their contents. Galactoceles are benign breast masses that contain inspissated milk; they are commonly found during or after lactation (11). Mammographically, they are small, round often multiple, radiolucent or mixed-density lesions, and they often occur in the retroareolar

area (11). The retention of lactiferous material accounts for the low density of these lesions (16) (Fig. 4.12). A fat-water level within a well-defined mass on a mediolateral view is pathognomonic of a galactocele (17) (Fig. 4.13).

area (11). The retention of lactiferous material accounts for the low density of these lesions (16) (Fig. 4.12). A fat-water level within a well-defined mass on a mediolateral view is pathognomonic of a galactocele (17) (Fig. 4.13).

Mixed-Density Circumscribed Masses

Fibroadenolipoma

A hamartoma or fibroadenolipoma is a benign tumor composed of normal mammary tissue (adipose, fibrous, and glandular), including ducts and lobules of varying amounts. The lesion is relatively uncommon, with a frequency of 16 in 10,000 mammograms in a series by Hessler et al. (18). In this series, the patients ranged in age from 27 to 88 years and presented with a breast mass of a consistency similar to that of the adjacent tissue (18).

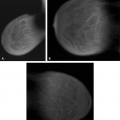

On mammography (Figs. 4.14,4.15,4.16,4.17,4.18,4.19,4.20,4.21,4.22), the appearance of a fibroadenolipoma is usually pathognomonic (18,19,20,21). Depending on the amount of fat versus parenchymal tissue, the lesion may vary from a relatively radiolucent mass to a relatively radiodense mass. The borders are very well defined, and a thin pseudocapsule may be evident. There is a loss of normal architecture of the mammary tissue with lack of orientation of glandular elements toward the nipple. The hamartoma displaces away the normal parenchyma of the breast, which appears to be draped over the lesion. Helvie et al. (22), however, found the mammographic findings of hamartomas to range from the mixed-density circumscribed mass to the isodense,

more irregular lesions that were biopsied because of the concern of possible malignancy.

more irregular lesions that were biopsied because of the concern of possible malignancy.

On sonography, the lesion is well defined and composed of lobulated sonolucent areas mixed with irregular echogenic planes (23). If large and cosmetically a problem, or if not clearly of mixed density mammographically, the lesion is treated with complete excision and enucleation. No association with malignancy has been described.

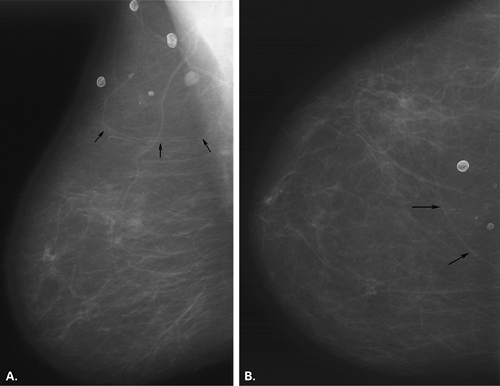

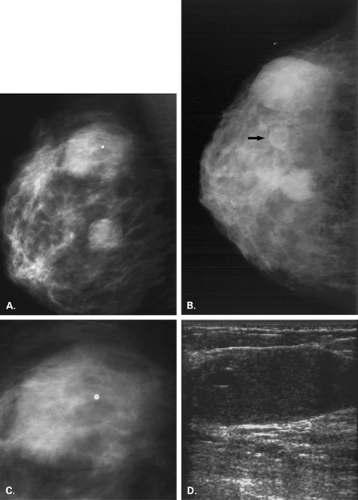

Intramammary Nodes

Intramammary lymph nodes have an appearance similar to that of axillary nodes; namely, they are well defined, mixed density or medium to low density, round, ovoid, or reniform nodules with a fatty notch or center (Figs. 4.23,4.24,4.25,4.26,4.27). Intramammary nodes can be found throughout the breast (24) but most commonly are located in the middle- to upper-outer aspect of the breasts and are

often multiple and bilateral. Intramammary nodes are located in the superficial soft tissue in the vast majority of cases.

often multiple and bilateral. Intramammary nodes are located in the superficial soft tissue in the vast majority of cases.

Most intramammary nodes are less than 1 cm in diameter. Nodes may increase in diameter and be benign, although if the mass does not have a fatty hilum, biopsy may be necessary to confirm its etiology. In a study of 158 whole-breast specimens with primary operable carcinoma, Egan and McSweeney (25) found intramammary lymph nodes in 28% and metastatic deposits in intramammary nodes in 10%. Although nodes involved with metastatic disease may enlarge and become more rounded and dense (24), this is not necessarily the case, and nodes of less than 1 cm in diameter can be malignant (25).

On ultrasound, lymph nodes also have a characteristic appearance. They are very well defined and oval or lobular with mixed echogenicity. The cortex is hypoechoic, and the fatty hilum is hyperechoic. Abnormal nodes may lose this appearance and be more rounded and poorly marginated.

Other benign conditions also may be associated with the presence of intramammary nodes as well as axillary adenopathy. These include rheumatoid arthritis (26), sarcoidosis (27), psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus (24). Enlarged dense nodes may be present in these conditions as well as in lymphoma. Often, in the case of adenopathy, the fatty hilum is lost and the node is isodense or even of high density.

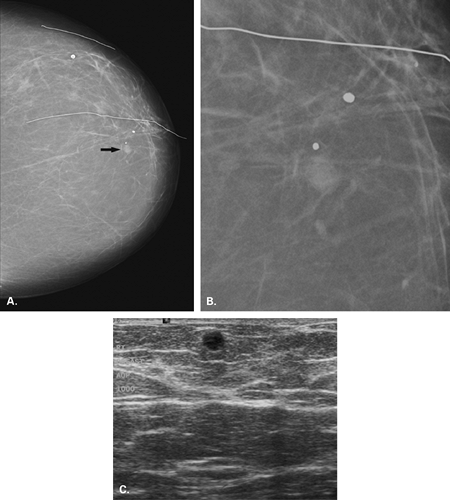

Skin Lesions

It is critical that the technologist indicate any skin lesions on the patient’s breasts. Moles, keratoses (Figs. 4.28,4.29,4.30), retracted nipples (Figs. 4.31 and 4.32), scars

(Fig. 4.33), and neurofibromas (Fig. 4.34) may appear as very-well-defined masses of mixed or medium density on at least one of the projections. As the lesion is compressed against the breast, air is trapped around it, creating an especially lucent halo. If the surface is irregular, a crenulated appearance is noted, creating a mixed density on mammography. By turning the breast with the lesion in tangent, the well-defined mass disappears or projects at the skin surface. Artifacts on the patient’s skin, including electrocardiogram pads and various patches for transdermal medications, may trap air underneath, producing a “mixed-density mass” appearance on mammography (Fig. 4.35).

(Fig. 4.33), and neurofibromas (Fig. 4.34) may appear as very-well-defined masses of mixed or medium density on at least one of the projections. As the lesion is compressed against the breast, air is trapped around it, creating an especially lucent halo. If the surface is irregular, a crenulated appearance is noted, creating a mixed density on mammography. By turning the breast with the lesion in tangent, the well-defined mass disappears or projects at the skin surface. Artifacts on the patient’s skin, including electrocardiogram pads and various patches for transdermal medications, may trap air underneath, producing a “mixed-density mass” appearance on mammography (Fig. 4.35).

Isodense to High-Density Masses

There is considerable overlap between the lesions that are of medium density or isodense with the background parenchyma and the lesions that are of high density (2). Cysts and fibroadenomas tend to be of isodense, and the background stromal markings may be visualized through the masses. Carcinomas tend to be of higher density, but these divisions are not absolute, and several benign lesions—including fibroadenomas, hematomas, and abscesses—may be of high density, depending on their

size. Margination of the mass is important in suggesting a malignant etiology. Also, a multimodality approach to these masses, including physical examination, mammography, and ultrasound, is important in determining the approach for further evaluation (28).

size. Margination of the mass is important in suggesting a malignant etiology. Also, a multimodality approach to these masses, including physical examination, mammography, and ultrasound, is important in determining the approach for further evaluation (28).

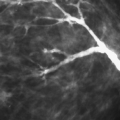

The sonographic features of a benign solid mass are a thin pseudocapsule (29), an ellipsoid shape, fewer than four gentle lobulations, and extensive hyperechogenicity (30). Based on these criteria, Stavros et al. (30) found the negative predictive value to be 99%. Although sonography cannot definitely differentiate benign from malignant solid masses, the correlation of a circumscribed mass that has not enlarged on mammography and benign sonographic characteristics can be used to follow rather than biopsy a nonpalpable lesion.

Malignant sonographic criteria (30) include spiculation, a taller-than-wide shape, angular margins, shadowing, branching pattern, hypoechoicity, duct extension, and microlobulation. The presence of these features, even in the face of a relatively circumscribed mass on mammography, should prompt biopsy.

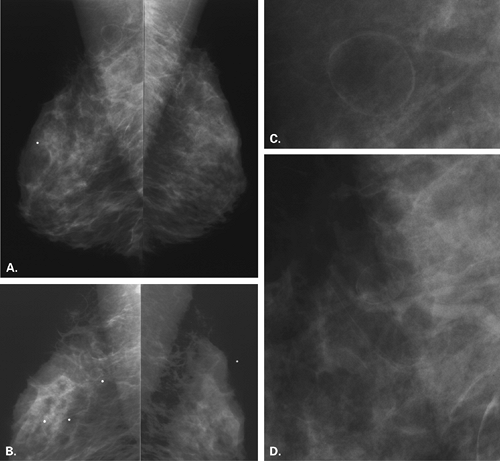

Cysts

One of the manifestations of fibrocystic disease is simple cysts that may vary from 3 mm to several centimeters in diameter. Cysts are more commonly seen in women 30 to 50 years old. Pain and tenderness may accompany the development of a cyst, and the symptoms may occur just before and with the menstrual cycle. There appears to be a relationship between caffeine consumption and fibrocystic disease. Boyle et al. (31) found that women who consumed 31 to 250 mg of caffeine per day had a 1.5-fold increase and those who consumed more than 500 mg/day had a 2.3-fold increase in the odds of fibrocystic disease. Allen and Froberg (32), however, found in a study of patients with suspected benign proliferative breast disease that a decrease in caffeine consumption did not result in a significant reduction of palpable breast nodules or in lessening of breast pain.

Cysts are derived from the lobules and may be lined by ordinary mammary epithelium or by an apocrine-type epithelium (33). A tension cyst is an apocrine cyst that contains fluid under pressure, secondary to obstruction of the outflow tract (33). Clinically, cysts are tender, circumscribed masses that are mobile, ranging from soft to firm, depending on the degree of distension.

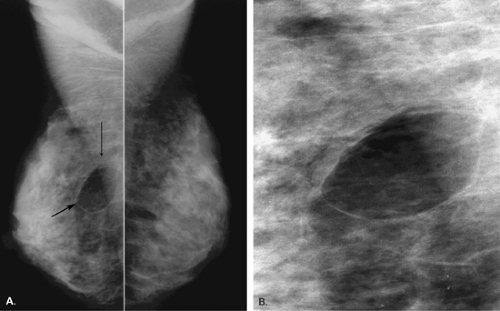

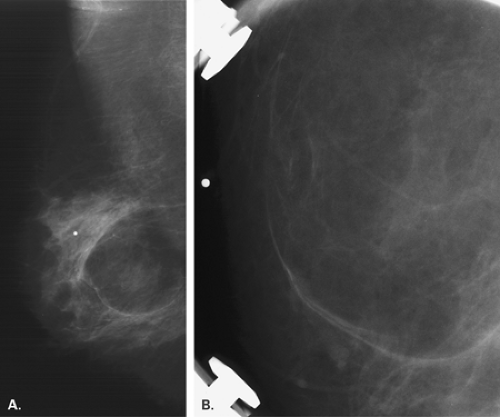

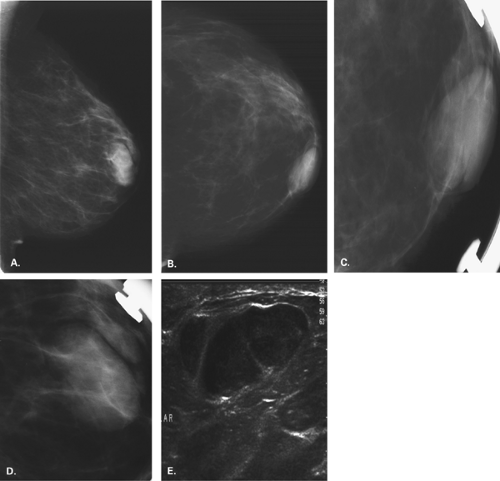

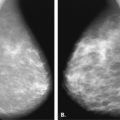

On mammography, cysts (Figs. 4.36,4.37,4.38,4.39,4.40,4.41,4.42,4.43) are very well-defined, round or ovoid masses that may vary from several millimeters to 5 cm or more in diameter (34). The density is usually equal to or slightly greater than that of parenchyma. A halo sign is often present, and the orientation of the cyst is along the path of the ducts. Cysts may be multilocular or multiple and may be associated with other findings of fibrocystic disease. It is important when multiple masses are present that each lesion be evaluated individually so that a well-defined carcinoma not be missed.

On sonography, cysts are well defined and anechoic, with well-defined walls and good through-transmission of sound. If echoes are present within a lesion thought to be a cyst, aspiration should be performed for complete evaluation. Pneumocystography also may be performed at the time of aspiration to outline the internal aspect of the cyst wall. When sonography demonstrates a complicated cyst (imperceptible wall, acoustic enhancement, and low-level echoes) or a cluster of microcysts, the likelihood of malignancy is very low.

Cystic masses with thick walls, thick septae, or an intracystic solid component or predominately solid masses with cystic foci are categorized as complex cysts. Complex cysts may be malignant, and biopsy is warranted. In a study of cystic lesions, Berg et al. (35) found that none of the 38 complicated cysts or the 16 clustered microcysts were malignant; however, 18 of the 79 complex masses were malignant. Papillomas and intracystic papillary carcinomas may develop within a cyst and usually cannot be

differentiated radiographically (36). Invasive papillary carcinomas tend to present as multiple, relatively well-defined masses. If a cyst contains an intracystic lesion, lobulation or slight irregularity of the wall may be seen on mammography. On pneumocystography, papillary lesions are seen as a polypoid filling defect within the cyst cavity.

differentiated radiographically (36). Invasive papillary carcinomas tend to present as multiple, relatively well-defined masses. If a cyst contains an intracystic lesion, lobulation or slight irregularity of the wall may be seen on mammography. On pneumocystography, papillary lesions are seen as a polypoid filling defect within the cyst cavity.

Fibroadenoma

A fibroadenoma is a benign tumor of the breast, usually presenting with a well-defined mass. The term fibroadenoma was first used by Bilroth in 1880 (37). Being estrogen-sensitive tumors, fibroadenomas usually appear in adolescents and young women before the age of 30 years. Their growth may be enhanced by pregnancy or lactation (38). After menopause, these tumors undergo mucoid degeneration, hyalinize, and eventually develop characteristic coarse calcifications.

Dupont et al. (39), in a study of 1,835 patients with fibroadenomas, found that there was a slight increase in the risk of breast cancer in women diagnosed with fibroadenoma. However, the histologic features of the fibroadenoma influenced the risk of breast cancer. Fibroadenomas with associated proliferative disease in the epithelium or in those patients with positive family history of breast cancer were considered to be at increased long-term risk.

In a study of the follow-up of fibroadenomas, Carty et al. (40) found that at 5 years after diagnosis, 52% of the fibroadenomas had reduced in size, 16% were unchanged, and 32% had grown. When fibroadenomas have been diagnosed based on a triple test of mammography, clinical examination, and cytology, or have been diagnosed on percutaneous tissue sampling with a core needle, usual management is follow-up rather than excision. If an incidental nonpalpable fibroadenoma is identified at mammography and confirmed as having benign sonographic features (30), early imaging follow-up rather than biopsy is typically performed.

On histology, fibroadenomas are composed of dense, connective-tissue stroma surrounding canaliculi or tubules lined with ductal epithelium (41). On clinical examination, these tumors are smooth and of firm or rubber consistency and freely movable. In young patients, fibroadenomas may reach a very large size. This variant, sometimes termed the juvenile fibroadenoma, is characterized by rapid growth rate in young women and an increase in stromal cellularity (42).

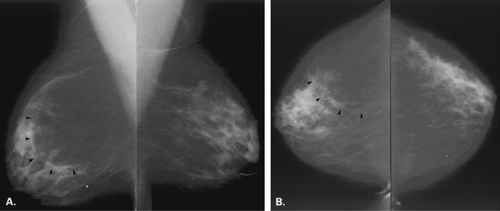

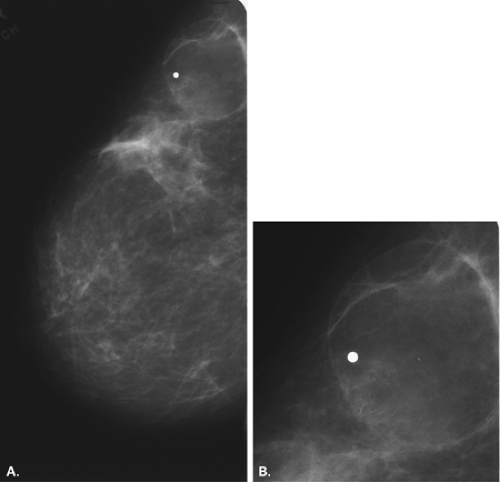

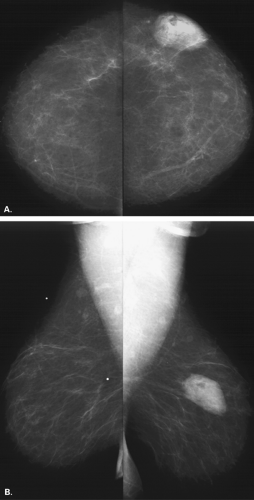

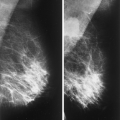

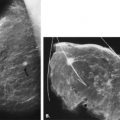

The mammographic findings (Figs. 4.44,4.45,4.46,4.47,4.48,4.49,4.50,4.51) of a fibroadenoma are an isodense, very-well-defined, round, ovoid, or smoothly lobulated mass (43). A fatty halo surrounds the lesion and may be the key to identifying a

fibroadenoma in a young dense breast. Calcifications may vary from punctuate peripheral deposits to the typical coarse popcornlike morphologies that are characteristic of fibroadenomas. On ultrasound, fibroadenomas are usually smooth, hypoechoic masses of homogeneous echo-texture with well-defined margins and no attenuation or enhancement of sound posteriorly (44) (Figs. 4.52 and 4.53).

fibroadenoma in a young dense breast. Calcifications may vary from punctuate peripheral deposits to the typical coarse popcornlike morphologies that are characteristic of fibroadenomas. On ultrasound, fibroadenomas are usually smooth, hypoechoic masses of homogeneous echo-texture with well-defined margins and no attenuation or enhancement of sound posteriorly (44) (Figs. 4.52 and 4.53).