Important immunologic discoveries including correlations with variations in human leukocyte antigen antigens have come about in the past decade. On a cellular level, pancreatic stellate cells are identified in their important role of extracellular matrix formation and fibrosis development. The understanding of the contribution of substance P, nerve growth factor, brain-derived growth factor, and other cell signaling molecules to disease pathogenesis is evolving. Elucidation of the mechanism of disease development on the genetic and cellular level explicates the concept of individual susceptibility in the face of environmental stressors.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients may present with complications of pancreatitis such as obstruction (biliary, duodenal, mesenteric vascular thrombosis), perforation (pseudocyst, pancreatic fistula, pancreatic ascites), or bleeding (visceral arterial pseudoaneurysm). The clinical hallmark of CP, however, is intractable, debilitating abdominal pain. Pain is reported by 80% to 94% of patients with CP. It is typically described as sharp and burning, located in the epigastrium and radiating around to the back. Nausea, emesis, and food intolerance often accompany the pain. Patients may not have objective findings associated with pain exacerbation episodes, such as serum amylase elevation, thus leading to challenges for health care workers and patients alike. Commonly, patients with severe disease are challenged in their relationships with family and health care workers and may develop maladaptive behaviors and associated social marginalization.

Endocrine and exocrine organ failure develops with progressive disease. Approximately 60% of CP patients will develop insulin-dependent diabetes. Greater than 90% loss of exocrine function must occur to result in malabsorption, with absorption of fat more significantly affected than protein.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of CP entails a consistent clinical history, notable for pancreatic-type abdominal pain, along with radiographic evidence of disease. The most relevant imaging modalities include contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), secretin-stimulated magnetic resonance pancreatography (MRP), endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP), and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

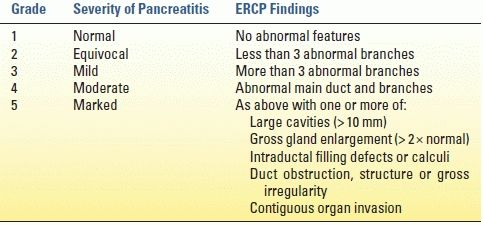

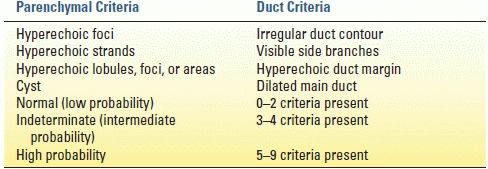

Abdominal CT may show calcifications, parenchymal thickening or atrophy, or pancreatic ductal dilation evidencing disease. Alterations in parenchymal enhancement, decreased response to secretin stimulation, and pancreatic ductal pathology such as strictures or dilation may be better delineated by MRP. ERP can show ductal changes and historically has been the gold standard of objective disease diagnosis, although MRP is quickly replacing ERP for diagnostic purposes at many centers. The ERP-derived Cambridge classification system is the standard disease grading system derived from an international consensus (Table 3.2). EUS is touted as the most sensitive of the imaging modalities, although its utility is limited by interobserver variability. It, too, has a disease grading system based on the identification of objective features of CP (Table 3.3).

TABLE 3.2 Cambridge Classification System for Severity of Chronic Pancreatitis by ERCP Imaging

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

From Sarner M, Cotton PB. Classification of pancreatitis. Gut 1984;25:756–759.

TABLE 3.3 Conventional EUS Criteria for Chronic Pancreatitis

EUS, endoscopic ultrasound

From Wallace MB, Hawes RH, Durkalski V, et al. The reliability of EUS for the diagnosis for chronic pancreatitis: interobserver agreement among experienced endosonographers. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:294–299.

MANAGEMENT

In CP patients with debilitating pain who have failed medical management to include alcohol and tobacco abstinence, pain control, nutritional optimization, and behavioral therapies, intervention is indicated for pain relief.

ENDOSCOPIC MANAGEMENT

Therapeutic ERP interventions for CP are undertaken with the goal of relieving an obstructive process. Maneuvers include sphincterotomy, stone extraction, stricture dilation, and stenting. In practice, the endoscopic approach is exhausted prior to surgery, given the perceived advantages of a less invasive procedure, despite two randomized controlled trials demonstrating improved outcomes with surgery in patients with obstructive pancreatopathy. In the first trial by Dite and colleagues from the Czech Republic, 72 patients were randomized to endoscopic or surgical intervention for pancreatic duct obstruction and associated pain. Endoscopic therapy consisted of 52% sphincterotomy and stenting and 23% stone removal. Operative management included 20% drainage procedures and 80% resections. At 5-year follow-up, the surgical group had a greater proportion of patients who were pain free (34% vs. 15%), while the rate of partial pain relief was equivalent between the groups (52% surgery, 46% endoscopy). In another trial by Cahen and colleagues from the Netherlands, 39 patients were randomized to endoscopic or surgical intervention for dilated duct pancreatitis and pain. Endoscopic therapy included sphincterotomy and stent, while operative therapy was with a longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy (LR-LPJ). At 5-year follow-up, pain relief was achieved in 80% of the surgical group versus 38% of the endoscopic group (p = 0.001). The surgical group also had larger improvements in quality of life and underwent fewer procedures. Equivalent morbidity, length of stay, and pancreatic function were seen in the two groups.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The primary indication for surgical intervention in CP is intractable pain, unresponsive to medical therapies. Forty percent to sixty-seven percent of patients with CP will meet these criteria for surgery. The goals of surgery are to effectively and durably relieve pain while minimizing morbidity including preserving pancreatic parenchyma when possible. The etiology of pancreatic pain is poorly understood and likely multifactorial. Thus, operative decision making can be challenging. The pancreatic ductal anatomy is the primary determinant in surgical planning. Generally speaking, patients with a large main pancreatic duct (> 6–7 mm in diameter) are presumed to have an obstructive component to their disease and are thus well served by a drainage procedure. In patients with small duct disease, resection of damaged and poorly drained parenchyma is typically effective. In patients with head-predominant or tail-centered disease, a directed resection is optimal. In patients with a small pancreatic duct and diffuse organ involvement, a total pancreatectomy (TP) with islet autotransplantation (IAT) may be indicated.

The heterogenous nature of CP anatomical changes mandates the surgeon’s familiarity with several operative approaches—no one operation is suitable for every patient.

Longitudinal Pancreaticojejunostomy

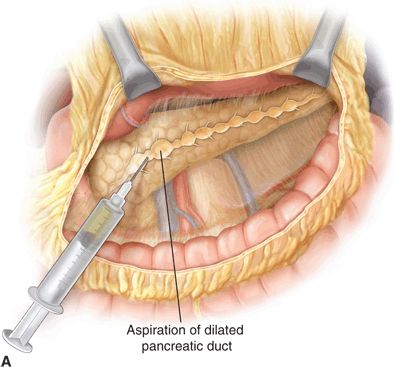

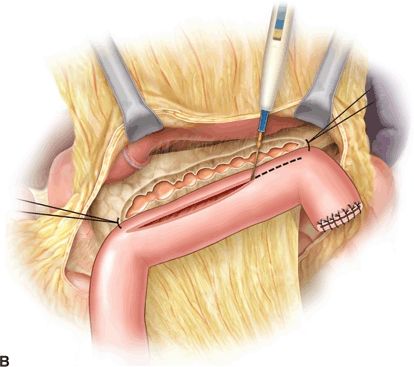

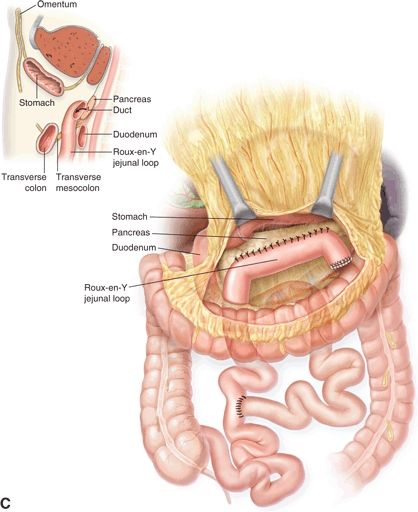

Operative pancreatic drainage for pancreatitis was described in a small series of patients by Puestow and Gillesby in 1957. A modification of this original drainage procedure that more closely resembles modern day technique was reported by Partington and Rochelle in 1960. The classic operation for pancreatic drainage, the lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (LPJ), entails opening the pancreatic duct anteriorly along its length within a fibrotic gland, medially to the level of the gastroduodenal artery. The opened pancreatic duct is then anastomosed to a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb (Fig. 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1 A. After exposure of the full length of the pancreas, the pancreatic duct is identified by aspiration using a 21-gauge needle on a 5-mL syringe. B. The Roux-en-Y limb is brought alongside the pancreas in an isoperistaltic fashion. The longitudinal pancreatic ductotomy is visible. Two corner stitches are placed between the jejunum and the apices of the ductotomy. An enterotomy is then made lengthwise along the jejunum, in parallel to the pancreatic ductotomy. C. A completed Roux-en-Y lateral pancreatojejunostomy. (From Lillemoe K, Jarnigan W, eds. Master techniques in surgery: hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013.)

Potential significant procedure-specific complications include intraoperative hemorrhage due to splenic vein or gastroduodenal artery injury, postoperative hemorrhage typically from the gastroduodenal artery, and anastomotic leak seen in 10% of cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree