Chronic Myeloid Leukemia

ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a clonal disorder of the hematopoietic stem cell affecting every lineage (except T lymphocytes). It affects about 5500 people a year in the United States and has a median age of onset in the sixth decade. The cause of CML is unknown.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

CML was one of the first human cancers associated with a chromosomal abnormality, the translocation 9;22, or Philadelphia chromosome. This translocation creates a novel fusion gene, bcr-abl, between the abl gene on chromosome 9 and the bcr gene on chromosome 22. The fusion gene protein product expresses an activated tyrosine kinase. The uncontrolled kinase activity of the bcr-abl takes over the normal functions of the normal ABL enzyme, causing unregulated cellular proliferation and decreased apoptosis.

NATURAL HISTORY

The disease is characterized by a stable phase that may be clinically silent and lasts 3–4 years. Accumulation of genetic damage over that time, particularly mutations in p53, can then lead to disease acceleration and a predominance of myeloblasts in the marrow and peripheral blood. Once disease acceleration occurs, median survival is usually less than 1 year. The development of acute leukemia may be of lymphoid, myeloid, or erythroid differentiation.

DIAGNOSIS

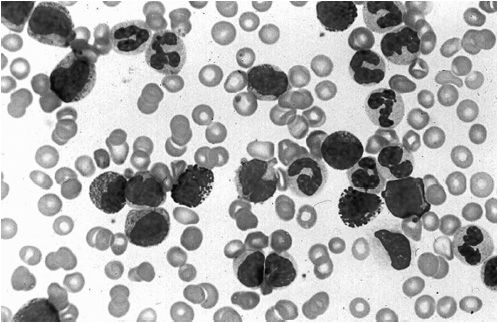

Most patients with CML, particularly in the stable phase (<5% myeloblasts in the bone marrow), are asymptomatic. An elevated WBC may be noted on a routine physical exam. Patients in accelerated phase (5%–20% marrow blasts) may have night sweats, adenopathy, and splenomegaly. The blast crisis (>20% marrow or blood blasts) has similar presentation to acute leukemia. The blood smear and bone marrow in CML will show an abundance of cells in all stages of maturation. (Figure 27-1). The definitive diagnosis can be made by the presence of the bcr-abl translocation in the blood or bone marrow, determined by PCR analysis. Variant chromosomes are seen in 5% of patients and do not affect prognosis (1).

FIGURE 27-1 Chronic myeloid leukemia in stable phase-peripheral blood. Early myeloid cells and basophilia are characteristic.

• Positive bcr-abl in blood or marrow diagnostic of CML—bone marrow not needed for diagnosis but helpful to rule out more advanced stage of disease.

• Chronic phase: high WBC, often asymptomatic, <5% blasts

• Accelerated phase: may be symptomatic, 5%–20% blasts

• Blast crisis: 70% present as a myeloid acute leukemia, 30% lymphoid, and

TREATMENT

The treatment for CML has changed dramatically since the approval of imatinib (Gleevec) in 2002 (2). Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks the kinase activity of bcr-abl and inhibits the proliferation of Philadelphia chromosome positive progenitors. Chronic phase disease is treated with imatinib at a dose of 400 mg/day. Approximately 95% of chronic phase patients receiving imatinib will have a complete hematologic response, 87% complete cytogenetic response, and 77% major molecular response (3) (see Table 27-1). After 2 years, CML progresses in 3% of patients with a major cytogenetic response (<35% Philadelphia positive metaphases) and 12% of patients without a major cytogenetic response (4). Side effects of imatinib include nausea, rashes, headache, diarrhea, fluid retention, and cytopenias. Patients who are intolerant of imatinib or who do not have a molecular remission should be switched to the second generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors dasatinib or nilotinib. These drugs induce a quicker molecular remission than imatinib, and may also be used for initial therapy (4). In a randomized trial, nilotinib yielded better progression-free survival, as compared to imatinib. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with a complete molecular response is controversial (5). Patients in remission should have peripheral blood monitoring for the bcr-abl transcript every 3 months until a major molecular response, and every 6 months thereafter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree