John E. Bennett

Chronic Meningitis

The focus of this chapter is on the differential diagnosis of chronic meningitis. The reader is referred to the chapters on individual infections for discussions of their management. Indolent infections in the spinal cord and brain present quite differently from those in the meninges and will be discussed briefly before turning to the topic of chronic meningitis.

Myelitis, Myeloradiculitis, and Polyradiculitis

Although “myelo” refers to spinal cord and “radiculo” refers to the nerve roots, infection of the spinal cord generally results in a pathologic process of the nerve roots and vice versa. The clinical presentation may be acute or chronic. Examples of acute presentations are transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, poliomyelitis, and infections due to West Nile virus and coxsackievirus. Chronic myeloradiculitis can result from syphilis (tabes dorsalis),1 human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (tropical spastic paraparesis),2 cytomegaloviral polyradiculopathy in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS),3 herpes simplex virus infection, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection, and schistosomiasis (usually caused by Schistosoma haematobium).4 Meningeal carcinomatosis, spinal cord tumors, and spinal epidermoid cysts may present as chronic myeloradiculitis. Patients with cat-scratch encephalomyelitis may present subacutely with spinal cord signs.5 Myeloradiculitis may be a prominent feature of tuberculous meningitis, but the severe systemic features of disseminated tuberculosis easily distinguish this entity from other causes of chronic myeloradiculitis. Initial symptoms of chronic myeloradiculitis commonly include decreased muscular strength in the extremities, loss of bladder control, and, less commonly, back pain or shooting pains in the torso or extremities. Examination may find decreased deep tendon reflexes, loss of proprioception in the extremities, decreased rectal sphincter tone, or decreased perception of pain or light touch in the extremities. Symptoms and signs are most marked in the lower extremities. Mild to moderate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pleocytosis and increased CSF protein level are usual, but hypoglycorrhachia is not found. Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show meningeal enhancement along the cord or cauda equina. Epidural or intradural abscess as well as malignant lesions causing spinal cord symptoms can be distinguished from myeloradiculitis on MRI.

The cauda equina syndrome is a constellation of neurologic symptoms and signs due to myeloradiculitis in the conus medullaris, including urinary incontinence, residual bladder urine, unilateral or bilateral leg or sciatic pain, leg weakness, saddle anesthesia, sexual dysfunction, and loss of ankle tendon reflexes. Some of the patients receiving Exserohilum-contaminated methylprednisolone injections developed the equina cauda syndrome as infection crossed the dura mater to form abscesses in the cauda equina.6

Encephalitis

Patients with encephalitis (see Chapter 91) most often present with an acute disease, although infection may be diphasic and sequelae may persist long after the acute infection has resolved. Indolent onset is usual in some causes of chronic encephalitis, such as syphilis (general paresis), subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (measles virus), Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi), African trypanosomiasis, Whipple’s disease (Tropheryma whipplei), bartonellosis (cat-scratch disease), autoimmune encephalopathy with anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antibody, HIV-1 infection, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (polyomavirus). Rabies is delayed in onset but rapidly becomes more severe once symptoms begin. Although chronic encephalitis symptoms overlap those of chronic meningitis, dementia and personality change are early and prominent signs in chronic encephalitis. Unlike acute presentations of viral encephalitis with fever and headache, patients with chronic encephalitis may have little fever or headache. Depending on the etiology, seizures and focal signs may occur. CSF pleocytosis and increased protein are usual, but hypoglycorrhachia is rare.

Brain Abscess

Brain abscess (see Chapter 92) may cause intense headache, but focal signs and seizures soon predominate. Like chronic meningitis, fever is not a predominant symptom in brain abscess. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is the most sensitive imaging technique for focal intracerebral lesions but does not reliably distinguish abscesses from tumors or intracerebral granulomas, such as those due to toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, or histoplasmosis. Cystic lesions and intracerebral calcifications of neurocysticercosis are well visualized by computed tomography (CT). Fluorodeoxyglucose-labeled positron emission tomography can be used alone or with CT to assess metabolic activity of the lesion, but distinction between infectious and malignant lesions is not simple.

Recurrent aseptic meningitis should be distinguished from chronic meningitis and should suggest herpes simplex virus (Mollaret’s meningitis), repeated episodes of drug-induced meningitis (e.g., from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or intravenous immune globulin), or epidermoid cysts and craniopharyngiomas intermittently discharging keratinaceous debris into the CSF.

Chronic Meningitis

Clinical Manifestations

For the purposes of this chapter, patients with chronic meningitis have the indolent onset of symptoms compatible with chronic central nervous system (CNS) infection for at least 4 weeks and have signs of chronic inflammation in the CSF.7–11 Chronic meningitis must be distinguished from recurrent aseptic meningitis or persistent sequelae of encephalitis. A careful history from the patient or family member may be needed to date the onset of symptoms and to distinguish chronic from recurrent meningitis. What may have seemed like a sudden onset may, on further questioning, have been the culmination of a much longer process. Symptoms of chronic meningitis can wax and wane over weeks and months. An abnormal result of CSF testing may not have been repeated to see if improved symptoms were accompanied by an improvement in CSF abnormalities. Early symptoms of chronic meningitis include headache, nausea, and decreased memory and comprehension. When hydrocephalus complicates indolent meningitis, dementia can be a prominent finding, which is better related by family members than by the patient. Later symptoms of chronic meningitis include decreased vision, double vision, cranial nerve palsies, unsteady gait, emesis, and confusion.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Patients with chronic meningitis may have a normal physical examination, including absence of fever. Neurologic examination is the most frequent abnormality, with decreased recent and remote memory, confusion, apathy, papilledema, and cranial nerve palsies, particularly sixth nerve palsy and deafness. As cerebral edema causes brain stem compression, upper motor neuron signs, increased deep tendon reflexes, ankle clonus, a positive Babinski’s sign, and finally Cheyne-Stokes respiration may be noted. Other than cranial nerve palsies, neurologic signs are decidedly symmetrical. Resting tremor, rigidity, and decreased mental acuity occasionally suggest Parkinson’s disease.

Skin lesions may be an important source of biopsy material in sarcoidosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, or sporotrichosis. Vitiligo and poliosis may suggest Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Lymphadenopathy may point toward sarcoidosis, lymphoma, or hematogenously disseminated tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. A dilated funduscopic examination may reveal retinal lesions of Behçet’s syndrome, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, or cryptococcosis. The Argyll Robertson pupil sign is highly suggestive of neurosyphilis.

History

Exposure history can be helpful in that coccidioidomycosis is rare in patients who have never been in the southwestern United States or northern Mexico (see later discussion). The endemic area for histoplasmosis is broad, although in the United States it is uncommon in the Pacific Northwest and Rocky Mountain states. Immigrants from countries where tuberculosis is prevalent are at increased risk for reactivation, as are patients who have lived in a household where someone had tuberculosis. Neurocysticercosis occurs in residents of endemic countries but rarely in travelers to these regions. Lyme borreliosis is endemic in the northeastern United States. A history of a typical lesion of erythema migrans may suggest the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Travelers outside the United States may have been exposed to Angiostrongylus or Brucella.

A patient’s occupation is rarely helpful diagnostically. Age is important, in that cryptococcosis is uncommon in the first decade of life. A history of multiple sexual partners, men having sex with men, injection drug use, or previous sexually transmitted disease should suggest the possibility of neurosyphilis or HIV-associated infections. Underlying disease is important in that AIDS and corticosteroid therapy are major predisposing factors to cryptococcal and Acanthamoeba meningitis.

Imaging

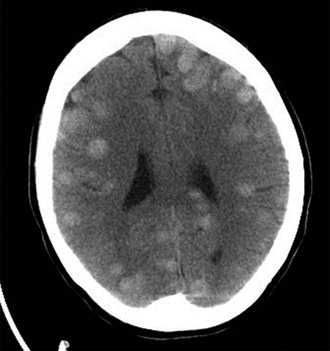

A contrast-enhanced MRI is the preferred test for imaging the brain and may show intracranial mass lesions, hydrocephalus (Fig. 90-1), or parameningeal foci, such as mold sinusitis or actinomycosis of the paranasal sinuses or middle ear.

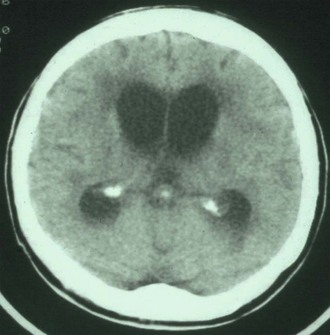

Increased intracranial pressure may be deduced from flattening of the sulci over the cerebral convexities, particularly in younger patients without preexisting atrophy. Increased width of the optic sheath may be evident in patients with cerebral edema or papilledema. Granuloma may be seen within the brain of patients with tuberculosis12 (Fig. 90-2) or cryptococcal or Histoplasma meningitis. Patients with blastomycosis or nocardiosis usually have one or more brain abscesses in addition to chronic meningitis. Spillage of the contents of an intracranial epidermoid cyst or craniopharyngioma may occur spontaneously or result from surgery. Rarely, repeated rupture can lead to chronic granulomatous meningitis.13 Epidermoid cysts are readily seen on MRI but must be distinguished from cystic tumors and cysticercosis.14

Laboratory Findings

Cerebrospinal Fluid

The opening pressure is usually elevated beyond 120 mm of fluid when measured with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. Glucose concentrations below 40 mg/dL are a valuable indication of fungal or mycobacterial chronic meningitis and are uncommon in syphilis, Lyme disease, parameningeal infections, or most noninfectious causes. Patients with the lowest CSF glucose level have the greatest increase in cell count and protein levels, but there is an exception to this rule. Profound hypoglycorrhachia with nearly normal cell count and protein levels should suggest carcinomatous meningitis. In infectious causes of chronic meningitis, a lymphocytic pleocytosis is usual but the cell count and cell type are variable, with a neutrophilic predominance not being rare. Culture of an adequate volume of CSF is imperative for optimal recovery of fungi and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Culture of at least 3 to 5 mL for fungi and an equivalent amount for mycobacteria is recommended. Microbiology laboratory technicians will need to be asked to culture the entire volume or may culture their usual volume, usually a milliliter or less, and save the remaining volume in the refrigerator.

Sampling the ventricular CSF is less helpful in chronic meningitis than sampling lumbar fluid. Ventricular fluid is often surprisingly normal, even in the absence of obstructive hydrocephalus and in the presence of very abnormal lumbar fluid. Postneurosurgical infections with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or a foreign body in the surgery site typically produce negative cultures of lumbar fluid, although cultures taken from an infected ventriculoperitoneal shunt or at neurosurgery in the area of the infection may be positive. Other potentially helpful tests are listed in Table 90-1. Lymphomatous meningitis may be diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of CSF in patients with nondiagnostic cytology results by showing a clonal population of lymphocytes having the same immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes.15 Flow cytometry of CSF can also be used to detect a malignant monoclonal lymphocyte population and lymphoblasts.16

Peripheral Blood

Serum serology can be helpful in the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis, brucellosis (agglutinin only), Lyme disease, and syphilis. In patients with a clinical syndrome compatible with neurosyphilis but a negative Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) or rapid plasmin reagin (RPR) test, a treponemal test should be requested. Positive treponemal tests preferably should be confirmed by a different treponemal test, because false-positive reactions occur. Serum cryptococcal and Histoplasma antigen tests can be done, although urine Histoplasma antigen testing is preferred over serum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree