Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Preetesh Jain

Kanti R. Rai

CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common leukemia (25% to 30%) in the Western world. The incidence of CLL in the United States is 3.5 cases per 100,000 people and the mean age at diagnosis is 65 years. The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program database reveals that the 5-year survival rate is 74%. Asian countries appear to have a much lower incidence. The main feature of CLL is a clonal accumulation of B lymphocytes with coexpression of CD5 with CD19 and CD23 and weak expression of SmIg, FMC7, CD22, and CD79b with κ or λ light-chain restriction. Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is CLL confined to lymph nodes or other tissues without peripheral blood involvement. The etiology of CLL remains unknown. It is not unusual to see an association of CLL with family history of cancers, immunodeficiency disorders, exposure to Agent Orange (a herbicide), and specific chromosomal aberrations, which are known risk factors of CLL. Contrary to other leukemias, exposure to radiation and cytotoxic agents are not associated with increased incidence of CLL. Considerable progress in elucidating the pathobiology and treatment of CLL has been made over the last two decades.1,2

Pathogenesis

A detailed discussion of pathogenesis of CLL is beyond the scope of this chapter. Factors that have helped in understanding of the disease include:

Apoptotic pathway defects (Bcl2 family proteins and Mcl1);

IgVH mutation status;

Immune dysfunction (hypogammaglobulinemia, T cells, and B-cell defects);

ZAP70 and CD38 status as prognostic markers;

Specific chromosomal aberrations (e.g., del13q14, trisomy 12, del11q, del17p, ATM and TP53 gene mutations;

B-cell receptor (BCR) abnormalities and activation of specific kinases.

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) has been identified as a possible precursor to CLL.3

Clinical Features

The natural history and clinical course of CLL are variable. The most common presenting features are peripheral blood lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, fever, night sweats, and weight loss may or may not be present. An increased incidence of infections (herpes viruses, bacterial, and Pneumocystis jirovecï) may occur because of immune function defects such as hypogammaglobulinemia, T-cell dysfunction, and B-cell defects. Anemia may be the result of marrow infiltration, chemotherapy, autoimmune hemolysis, and pure red cell aplasia. Other organs can also be affected in CLL (lungs, bones, kidneys, and skin). An exaggerated skin reaction to an insect bite is frequent in CLL (Well’s syndrome). Infrequently, CLL can also transform into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Richter transformation) and prolymphocytic leukemia (PLL), which have dismal prognoses.1

Diagnosis

Investigations

Complete blood count (CBC), differential and platelet counts, and review of the peripheral blood smear for lymphocyte morphology are the most appropriate initial investigations. Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood (PB) to demonstrate the presence of specific immunophenotype of CLL cells is required (see below under diagnostic criteria). Other tests at the time of diagnosis include serum LDH, comprehensive metabolic panel, FISH, and cytogenetics for chromosomal aberrations, direct antiglobulin test, serum immunoglobulins, and viral serology (HBV, HIV). Bone marrow biopsy is not required for diagnosis but is recommended prior to initiation of therapy. Other investigations such as serum levels of β2 microglobulin, thymidine kinase, soluble CD23 are being explored to determine if they are of help in establishing disease prognosis.

International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (IWCLL) Diagnostic Criteria for CLL (2008)4

≥5,000 B lymphocytes per µ/ in the peripheral blood for duration of at least 3 months.

≤55% prolymphocytes in the peripheral blood.

PB flow cytometry showing coexpression of CD5 and B-cell surface antigens CD19, CD20, and CD23, low levels of sIg, CD20, CD79b, and κ or λ light-chain restriction.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions that mimic CLL are benign atypical lymphocytosis in adults (viral infections such as EBV), hairy cell leukemia, and leukemic phase of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) such as mantle cell lymphoma, follicular and lymphoplasmacytic

lymphomas, and splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes, large granular lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma, and PLL. These can be differentiated from CLL based on specific immunophenotype and morphology.

lymphomas, and splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes, large granular lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma, and PLL. These can be differentiated from CLL based on specific immunophenotype and morphology.

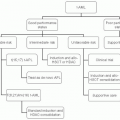

Clinical Staging System and Prognostic Factors

Clinical Staging

The Rai and/or Binet clinical staging systems are used in CLL. These systems are based on the extent of involvement of peripheral blood, organs, and bone marrow by CLL lymphocytes. The Rai staging classification is divided into low risk (stage 0), intermediate risk (stages I and II), and high risk (stages III and IV). Stage 0, lymphocytosis only, lymphadenopathy in stage I, and hepatosplenomegaly in stage II, marrow infiltration-induced cytopenias (anemia in stage III and thrombocytopenia in stage IV). Median survival based on modified Rai stages is 10, 7, and 2 years, respectively. These survival times are similar to those of Binet stages A, B, and C.

Factors Predicting Poor Outcomes in CLL

A number of factors have been identified as surrogate markers for worst prognosis in CLL and have been used in clinical practice and clinical trials: Advanced Rai and Binet clinical stages, short lymphocyte doubling time (LDT) <6 months, diffuse pattern of bone marrow lymphocyte infiltration, elevated LDH, unmutated IgVH genes, VH3.21 gene usage (independent of IgVH mutation status), del(11q) and del(17p) using interphase FISH, positive ZAP-70, CD38 positive, and elevated β2 microglobulin.

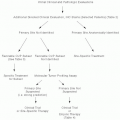

MANAGEMENT

Considering the heterogeneity among CLL patients in terms of disease course and prognosis, the decisions for selecting the type of therapeutic regimen should be made based on each patient’s presenting features.

Indications for Treatment (IWCLL Guidelines-2008)4

Evidence of progressive marrow failure as manifest by worsening anemia and/or thrombocytopenia.

Massive (>6 cm below the left costal margin) or progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly.

Massive nodes (>10 cm in the longest diameter) or progressive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy.

Progressive lymphocytosis with an increase of >50% over a 2-month period or lymphocyte doubling time of <6 months.

Autoimmune anemia and/or thrombocytopenia poorly responsive to corticosteroids or other standard therapy.

A minimum of any one of the following disease-related symptoms (unintended weight loss of ≥10% body weight within 6 months, significant fatigue (ECOG performance status [P.S.] ≥2), fever of >100.5°F or 38.0°C for 2 or more weeks without infection, night sweats >1 month without infection).

Response Assessment

Response to therapy is assessed4 3 months after the completion of therapy: CR (complete remission): no evidence of significant lymphadenopathy, or hepatosplenomegaly on physical examination with normal blood counts, no constitutional symptoms, and absence of CLL in the marrow (which should be normocellular). CRi (CR with incomplete marrow recovery), PR (partial response) ≥50% decrease in lymph nodes size and organomegaly (if previously enlarged) and improved Hb (>11 g per dL) and blood counts (neutrophil count >1.5 × 109 per L and platelets >100 × 109 per L or ≥50%) over baseline, with evidence of residual disease in marrow. Progressive disease (PD), stable disease, and nonresponses are considered as treatment failure.

Chemotherapy and Chemoimmunotherapy

Following the recent successes in therapy5,6,7, many investigators are now discussing whether a cure of this disease can now be considered a practical goal. The results of recent large clinical trials have demonstrated chemoimmunotherapy as the standard of care for a large majority of CLL patients. P.S. and clinical findings are the usual basis to determine the selection of regimen.

Single Agents

Purine Analogs

Fludarabine (F) has been shown to be superior to chlorambucil in CR rates (20% vs. 4%) as well as overall survival (OS) (8-year OS 31% and 19%, respectively, P = .04).8 Cladribine has also been shown to be superior to chlorambucil with high CR rates (47% vs. 12%). The use of nucleoside analogs (fludarabine, cladribine, or pentostatin), however, is associated with marked immunosuppression and opportunistic infections. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) has been reported following fludarabine therapy. The dosages of purine analogs when used as monotherapy are—Fludarbine (F)—25 mg per m2 IV daily for five consecutive days every 4 weeks for four to six cycles or as an oral formulation used as 40 mg per m2 daily for days 1 to 5 every 4 weeks for four to six cycles; Cladribine (2-CdA)—0.14 mg per kg daily IV over 2 hours for five consecutive days every 4 to 5 weeks for four to six cycles. Pentostatin (P) is given as 4 mg per m2 IV every 2 weeks for four to six cycles.

Alkylating Agents

These agents are effective for palliative therapy and for frail patients and are associated with low CR rates. Chlorambucil is given as 0.1 mg per kg PO daily for 3 to 6 weeks as tolerated or as 15 to 30 mg per m2 PO is given over a single day or divided over 4 days every 2 to 3 weeks, with or without prednisolone. Cyclophosphamide (C) is given as 2 to 4 mg per kg PO daily for 10 days, then adjusted based on desired responses. Bendamustine (B) A randomized phase III trial9 comparing bendamustine with chlorambucil showed superiority of B in terms of the overall response (OR), 68% for B versus 31% for chlorambucil,

and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 22 months for B and 8 months for chlorambucil (both P < .0001). Bendamustine is used in frontline as a single agent 100 mg per m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for six cycles.

and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 22 months for B and 8 months for chlorambucil (both P < .0001). Bendamustine is used in frontline as a single agent 100 mg per m2 on days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks for six cycles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree