There are a wide variety of histologic subtypes that are diagnosed within the uterine corpus. They will be discussed separately, as the treatments for each have evolved down divergent pathways. In the United States, approximately 43,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, with just over 7,000 deaths.

1 A much larger percentage of women survive cancer of the uterus compared with ovarian cancer, largely because to the fact that most women are diagnosed with uterine cancer at an early stage. In fact, 70% of uterine cancers are confined to the uterus at the time of diagnosis, and 88% are limited to the pelvis.

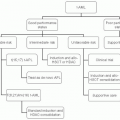

1 Uterine cancer is a surgically staged disease, although that staging is different for carcinomas and for sarcomas. Furthermore, prognosis is as related to tumor histology as it is to stage, with some cancer types, such as serous carcinoma, having high rates of recurrence, even when diagnosed in stage I.

Endometrioid Carcinoma

Endometrioid carcinoma is by far the most common type of uterine cancer, with 85% of uterine corpus carcinomas displaying this histology. It is more frequently diagnosed at an earlier stage than at nonendometrioid types, with 87% diagnosed in stage I or II, compared with 70% and 57% for clear cell and serous carcinomas, respectively.

2As with all uterine cancers, endometrioid carcinomas have historically been treated with surgery and, for those with a high risk of recurrence, adjuvant radiation.

3 However, several randomized trials have called into question the efficacy of radiation in the adjuvant setting for high risk, early stage disease. It has been well demonstrated that high risk, early stage endometrial cancers have fewer pelvic recurrences with adjuvant radiation.

4 However, these same trials have consistently demonstrated that patients receiving radiation have no added overall survival (OS) benefit.

4,5,6It has further been suggested that, even among patients with early stage disease, chemotherapy may provide improved benefit over radiation in the adjuvant setting. In a randomized phase III trial comparing pelvic external beam radiotherapy (PRT) with cyclophosphamide (333 mg per m

2), doxorubicin (40 mg per m

2), and cisplatin (50 mg per m

2) (CAP chemotherapy) every 4 weeks, the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG) found no difference in progression-free survival (PFS) or OS among low to intermediate-risk patients (i.e., those who have >50% myometrial invasion but are 70 years old or younger and have either grade 1 or 2 disease). However, for patients who are older than 70 years, have grade 3 disease, are stage II, or had positive pelvic washings, PFS was significantly improved for those receiving chemotherapy compared with the PRT group.

7 For patients with stage IIIA disease that had more than just positive cytology or for patients with stage IIIB or IIIC disease, no difference in PFS or OS was demonstrated. However, such subset analyses should always be interpreted with caution.

Alternatively, GOG-122 compared whole abdominal radiation (WAR) with doxorubicin 60 mg per m

2 and cisplatin 50 mg per m

2 every 3 weeks for seven cycles (AP), followed by one cycle of cisplatin, in patients with stages III and IV endometrial cancer. They reported a significant improvement in both PFS and OS for patients receiving chemotherapy.

8 Following this, GOG-177 randomized stages III, IV, and recurrent patients to receive either doxorubicin and cisplatin (AP) or

paclitaxel, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (TAP).

9 The three-drug regimen demonstrated significant improvements in response rate (57% vs. 34%), PFS (median, 8.3 vs. 5.3 months), and OS (median, 15.3 vs. 12.3 months), although with some increased toxicity. This study allowed prior radiation and/or hormonal treatment.

Subsequently, GOG-184 randomized patients with stages III and IV endometrial cancer into pelvic radiation ± vaginal brachytherapy, and doxorubicin and cisplatin, with or without paclitaxel. They did not demonstrate a PFS or OS advantage with the addition of paclitaxel, although toxicity was noted to be considerably higher.

10 They did, however, report an improved recurrence-free survival for patients with gross residual disease following surgery after receiving the three-drug regimen. The JGOG further compared the doublet regimens docetaxel and cisplatin, docetaxel and carboplatin, and paclitaxel and carboplatin, in a randomized, phase II trial.

11 They reported response rates of 51.7%, 48.3%, and 60.0%, respectively. Toxicity profiles were not significantly different. GOG-209, a randomized phase III trial comparing TAP with paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with advanced and recurrent disease has completed enrollment and is awaiting data maturation.

Uterine Serous Carcinoma

Uterine serous carcinoma, also known as uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC), has a much greater propensity for early, distance metastases and a worse prognosis than its endometrioid counterpart. It has been reported that as many as 67% of patients with no myometrial invasion have extrauterine disease at the time of surgical staging.

12 Others have reported extrauterine disease in as many as 38% of patients with UPSC found only in an intrauterine polyp.

13 As such, some authors have advocated the use of routine peritoneal biopsies and omentectomy during surgical staging.

14,15 However, Gehrig et al.

16 reported that microscopic disease within the omentum, in the absence of other gross extrauterine disease, was not demonstrated. Unlike endometrioid type, pelvic and periaortic lymph node dissection should be performed regardless of the myometrial depth of invasion.

Owing to the rarity of this disease, there is an obvious lack of randomized, controlled trials. However, based on retrospective studies, there appears to be improved survival with optimal surgical cytoreduction.

17,18,19 Thomas et al.

20 reported on 70 patients with stage IIIC or IV UPSC. Median survival of 20 and 12 months (

P = .02) was observed for optimally and suboptimally cytoreduced patients, respectively.

Likely secondary to the propensity for this disease to spread peritoneally and systemically, there has not been reported sufficient evidence to support the notion that radiation therapy is of any value. In fact, recurrence rates and median survival have been reported as similar for those who have and have not received WAR with a pelvic boost, regardless of stage.

21,22 In many such studies, it is as common, if not more so, for recurrences to occur within the radiated field, than outside of it. Nonetheless, data are conflicting and it is not uncommon for authors to recommend either brachytherapy or volume-directed radiotherapy, in combination with chemotherapy, for patients with early stage or locally advanced UPSC.

23Although several randomized studies have included patients with UPSC in evaluating the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of endometrial cancer, there have been no statistically valid subanalyses. It is quite clear that patients with any myometrial invasion are at significant risk of recurrence, and they should be treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Although the endometrial cancer staging (

Table 36-1) equates patients with disease confined to the endometrium with <50% myometrial invasion (stage IA), they are clearly not equivalent with regard to UPSC. In the largest retrospective study on stage I UPSC to date, Fader et al.

24 noted a significantly lower recurrence rate for those that received adjuvant platinum/taxane chemotherapy, with or without radiation, than for those that received no therapy or radiation alone, 11% versus 27%, respectively. The impact of chemotherapy was greatest for patients with myometrial invasion (former stages IB and IC), and on multivariate analysis, only chemotherapy and substage-impacted survival.

Unfortunately, for disease confined to the endometrium, the data that do exist are conflicting. Fader et al. reported recurrence rates of 16, 44 days 60% for patients with stage IA limited to the endometrium (former stage IA), stage IA with <50% myometrial invasion (former, stage IB), and stage IB (former stage IC), respectively, for patients not receiving any adjuvant treatment. Although some small studies have reported recurrence rates of 0% to 5% in patients with former stage IA disease, the majority of studies suggest that a rate is between 10% and 20%.

22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 This is in contrast to a rate of recurrence ranging from 24% to 80% for patients with stage I disease and any myometrial invasion. Overall, the rates of recurrence published in these small, retrospective studies appear to be lower for patients receiving chemotherapy, with or without radiation, and range from 0% to 17% for stage I disease confined to the endometrium, and 0% to 27% for patients with myometrial invasion. It is also important to note that the rate of cure or salvage for patients with recurrent UPSC is low, regardless of the location.

There is little controversy surrounding the need for adjuvant treatment in patients with advanced stage UPSC. The gold standard for the treatment of advanced endometrial cancer in general has arisen from five randomized GOG studies, as described previously. Among the patients enrolled in these studies, 13% to 17% had UPSC histology. Although GOG-177 demonstrated a survival advantage with the addition of paclitaxel to the regimen of doxorubicin and cisplatin, GOG-184 demonstrated no such advantage.

9,10 The notable difference between those being that GOG-184 included pelvic radiation in all participants, whereas GOG-177 included radiation in approximately half of the patient population. In GOG-184, the three-drug regimen demonstrated improved recurrence-free survival in patients with gross residual disease, which remained significant in multivariate analysis. There was a trend toward improved survival in patients with UPSC histology, although this did not reach statistical significance.

Clear Cell Carinoma

As with UPSCs, uterine clear cell carcinomas (UCCC) are relatively rare, representing 1% to 5% of endometrial cancers.

31 Much of the data available simply represents an inclusion of these cancers in much larger studies evaluating the prognosis and treatment of all types of endometrial cancers.

9,10Although some investigators have suggested a poorer overall prognosis for patients with clear cell carcinoma, others have found no significant difference between patients with this histology and grade 3 endometrioid controls.

31,32,33,34 As with UPSC, it has been reported that extrauterine spread of disease is more common with UCCC than with endometrioid tumors, and that such spread does not necessarily correlate with intrauterine predictors, such as depth of invasion.

35 As such, these patients should all undergo a thorough staging operation, including pelvic and periaortic lymph node evaluation.

With regard to the use of adjuvant chemotherapy, an extrapolation from the GOG studies, of which clear cell carcinoma was a minority subgroup, would suggest the use of doxorubicin in combination with a platinum regimen. However, many authors advocate the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with both early (former stages IB to II) and advanced stage disease.

36,37 Although many important questions may not be answered in this UCCC patient subset, GOG-209 will include such patients in comparing the doxorubicin-containing three-drug regimen with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Adjuvant radiation therapy is of unproven benefit in this patient population, although it was included and administered to all patients in GOG-184.

Leiomyosarcoma

Uterine sarcomas are rare tumors that account for 3% to 7% of all uterine malignancies.

38,39 Leiomyosarcomas (LMS) and carcinosarcomas (CS) each represent approximately 40% of uterine sarcomas, whereas endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) and undifferentiated sarcomas make up the other 20%.

40 Patients diagnosed with stage I or II LMS have recurrence rates as high as 50% to 80%.

41,42,43 Authors have reported inconsistent and conflicting effects of several clinical and pathologic features on prognosis, including the presence of necrosis, menopausal status, margin type, tumor size, stage, nuclear atypia, and mitotic count. Most consistently, higher stage and mitotic count appear to be associated with a higher likelihood or recurrence.

43,44,45,46At this point, surgical staging is generally consists of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy only (

Table 36-2). However, in a large, population-based study of nearly 1,400

patients with LMS, Kapp et al.

47 demonstrated that the inclusion of oophorectomy was not associated adversely with survival. Furthermore, they reported positive lymph nodes in only 6.6% of the 348 patients who underwent lymphadenectomy, 70% of whom had other extrauterine disease. Unfortunately, despite the high recurrence rate, no adjuvant regimen has demonstrated improved survival for patients with early stage disease. Reed et al.

48 randomized 224 patients with stages I and II uterine sarcomas, including 103 patients with LMS to receive either postoperative pelvic radiation or observation. For patients with LMS, they reported no improvement in local control, disease-free survival, or OS compared with the observation-only group. Several retrospective studies have suggested improved pelvic control with adjuvant radiation, and it continues to be recommended in some guidelines.

49,50In the only randomized trial addressing chemotherapy for patients with early stage uterine sarcoma, GOG-20 randomized 156 patients into receiving adriamycin or no further treatment.

51 Patients were allowed to have had radiation prior to enrollment. There was no difference between groups in either PFS or OS, and radiation did not seem to influence the outcome. It should, however, be noted that this was a relatively small study with a heterogenous group of different tumor types. The combination of docetaxel and gemcitabine has emerged as the primary regimen for the treatment of recurrent and metastatic uterine LMS, after studies have demonstrated response rates between 35% and 53%.

52,53 Although various regimens have been reported, the latest GOG study used gemcitabine 900 mg per m

2, on days 1 and 8, plus docetaxel 75 mg per m

2 on day 8, with granulocyte growth factor support on day 9 of a 21-day cycle. Hensley et al.

43 evaluated the adjuvant use of this regimen in patients with stages I through IV and concluded that the patients appear to have done better than historical controls. Unfortunately, there is no definitive evidence that this or any other chemotherapy regimen is of benefit in the adjuvant treatment of early stage LMS.

Carcinosarcoma

CS, or malignant mixed mullerian tumor (MMMT) as it has been formerly known, is slightly more common than LMS. Unlike LMS, however, CS has a rate of lymph nodal metastases of 14% to 38%.

41,54 Despite this, the role of lymphadenectomy in the surgical staging of CS remains controversial.

54,55 In a population-based analysis of 1,855 patients with CS, an OS of 54 and 25 months was reported for those who did and did not undergo lymphadenectomy, respectively. Akahira et al.

56 also demonstrated an improved survival for patients undergoing lymphadenectomy, whereas Temkin et al.

57 reported that patients having >11 lymph nodes removed had significantly improved disease-free and OS compared with those that had fewer lymph nodes excised. Others have not noted a significant benefit to performing lymphadenectomy in this patient population.

58,59As stated in the previous section, Reed et al.

48 reported on 224 patients with uterine sarcomas, of which 91 were CSs, randomized to receive radiation or observation only. For the subset of patients with CS, they reported a trend toward improvement in locoregional control with higher rates of distant metastases. There was no difference in disease-free or OS. Furthermore, GOG-150 randomized 206 patients with stages I through IV CS to receive whole abdominal irradiation (WAI) or cisplatin and ifosfamide with mesna (CIM).

60 They reported a nonsignificant trend toward improved disease-free and OS for the CIM arm, with a favorable toxicity profile. GOG-108 randomized 194 patients to receive ifosfamide with or without cisplatin for eight cycles.

61 They reported a significant improvement in PFS for the combination arm, with gains in OS not reaching significance. Lastly, GOG-161 randomized 179 patients with advanced, persistent, or recurrent CS to receive ifosfamide 2.0 g per m

2 intravenously (IV) daily for 3 days or ifosfamide 1.6 g per m

2 IV daily for 3 days plus paclitaxel 135 mg per m

2 by 3-hour infusion on day 1, for up to eight cycles.

62 Both arms included mesna. Both PFS and OS were improved in the combination arm. At present, there is no definitive evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy is beneficial in early stage CS. However, it should be noted that Reed et al. noted a 3-year disease-free survival of only 51% in the above-mentioned study consisting mostly of patients with LMS and CS.

Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

ESS make up a small fraction of all uterine sarcomas. The diagnosis has recently undergone a recent reclassification to remove the high-grade lesions and place them in a separate category called undifferentiated sarcomas. Typically, ESS exhibits a rather indolent behavior, with a tendency to recur years or even decades after diagnosis. They are frequently estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive, and as such, have been the subject of studies investigating the value of hormone manipulation. ESS has a relatively low likelihood of lymph node metastasis in the absence of gross extrauterine disease, deep myometrial invasion, or lymphovascular space invasion.

63 Therefore, it is not routinely recommended that patients with ESS undergo lymph node dissection. Surgical staging does, however, include hysterectomy, although bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is also controversial, given that many of these women are premenopausal at the time of diagnosis.

63,64 There have been some reports of fertility sparing attempts in such patients, with mixed outcomes.

65,66Some authors have reported improved survival with the use of adjuvant progestin therapy in patients with ESS.

67 Although a small, retrospective analysis, Chu et al.

64 reported recurrence rates of 31% and 67% for those who did and did not receive adjuvant progestins. With regard to advanced and recurrent disease, there have been several reports of complete and sustained responses with progestin therapy alone, such as megestrol acetate 200 to 800 mg per day.

68,69,70 Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists, such as goserelin, and aromatase inhibitors, such as anastrozole, have also been reported to have sustained responses in patients with advanced and metastatic ESS.

71 When hormonal therapy has failed, cytotoxic chemotherapy is an option, although with limited success. Activity has been demonstrated against ESS using ifosfamide with or without cisplatin or doxorubicin.

72,73,74 Most of the data with regard to the

use of cytotoxic agents is derived from the treatment of what was formerly known as “high-grade” ESS.