Cervical Mediastinoscopy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Nodal Station Assessment

Patient Eligibility

Preparing for Complications

1. NODAL STATION ASSESSMENT

Recommendation: Cervical mediastinoscopy can be used to evaluate lymph node stations 2R, 2L, 4R, 4L, and 7.

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Lung cancer patients with stage IIIA (ipsilateral) or stage IIIB (contralateral) mediastinal node involvement have poor long-term survival. The mediastinal nodes should be assessed before lung resection in patients who have accessible mediastinal lymph nodes that are greater than 1.5 cm in diameter and/or that positron emission tomography findings reveal to be positive. Patients without these characteristics but who nevertheless have a high likelihood of mediastinal nodal involvement should also undergo mediastinal lymph node assessment before lung resection. Such patients include those with tumors larger than 3 cm in diameter, central tumors (involving the inner third of the lung), and/or tumors of specific histologic types (i.e., large cell, neuroendocrine, and small cell tumors and adenocarcinomas) and/or those with multiple lung lesions. Patients who have tumors with a maximum standardized uptake value greater than 4 and/or positive N1 nodes on positron emission tomography (PET) should also undergo mediastinoscopy to assess the mediastinal nodes.

Mediastinal lymph nodes can be assessed using endobronchial ultrasonography or cervical mediastinoscopy. Cervical mediastinoscopy can be used to evaluate lymph node stations 2R, 2L, 4R, 4L, and 7. Endobronchial ultrasonography can evaluate these stations as well as station 10 and the hilar nodes in stations 11 and 12. The technique chosen depends on the surgeon’s preference, institutional expertise, and the contraindications to cervical mediastinoscopy. A broad discussion of the available modalities is found in Chapter 5, Invasive Mediastinal Staging Overview.

2. PATIENT ELIGIBILITY

Recommendation: Caution and good surgical judgment should be exercised when offering cervical mediastinoscopy to patients with superior vena cava syndrome, abnormal anatomy, prior treatment to the operative field, and coagulopathy.

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Several authors have reported series of patients with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome who underwent cervical mediastinoscopy. In these three series, 1 of 14 (7%) patients, 5 of 80 (6%) patients, and 2 of 39 (5%) patients, respectively, had significant bleeding requiring sternotomies. Airway obstruction due to hematoma was a life-threatening complication in one series. No patients in the three series died from undergoing mediastinoscopy. This complication is higher than reported in large series of patients without SVC syndrome undergoing this procedure.1,2,3

Anatomic characteristics that would exclude patients from mediastinoscopy include aortic arch aneurysm and innominate artery calcification, which increase the risk for stroke, and existing tracheostomy. Patients who have limited neck mobility, including those with ankylosing spondylitis, also would not be candidates for cervical mediastinoscopy.

Patients who have received remote neck and chest radiation, as well as those who have had recent adjuvant chemo- or radiotherapy, are candidates for mediastinoscopy. Mediastinoscopy can be repeated in patients who have received radiotherapy and in patients who present with a second malignancy. However, these patients may have inseparable adhesions that make performing repeat mediastinoscopy difficult. In addition, the lymph node sampling of a repeat mediastinoscopy is less sensitive than that of the primary mediastinoscopy.

Prior median sternotomy for cardiac surgery is not a contraindication to mediastinoscopy. Cardiac surgery typically does not violate the dissection plan used for mediastinoscopy, and mediastinoscopy outcomes in patients who have or have not had previous cardiac surgery are similar.

Nevertheless, surgeons should exercise good surgical judgment before offering mediastinoscopy and then intraoperatively in patients who have SVC syndrome or who have already undergone mediastinoscopy, have received neck radiation, or have undergone median sternotomy.

3. PREPARING FOR COMPLICATIONS

Recommendation: Proper preparation of both the patient and the operating room team and the use of video mediastinoscopy are essential to effectively managing emergency complications during cervical mediastinoscopy.

Type of Data: Retrospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Although rare, complications during cervical mediastinoscopy have been described. To ensure the successful and safe completion of the procedure, the entire operative team must be prepared to manage any complications, and the patient should be properly positioned and draped. These precautions will result in better outcomes with less morbidity.

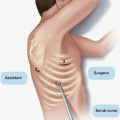

The patient should be supine, with a roll placed transversely beneath the shoulders. The neck should be extended maximally and the head supported. The trachea should be easily palpable. Once the patient is under general anesthesia, an arterial line or pulse oximeter is placed in the right upper extremity to detect prolonged compression of the innominate artery. The availability of blood for potential transfusion should be confirmed. The draping should include the neck and chest in the unlikely event of lifethreatening hemorrhage, airway injury, or pneumothorax requiring urgent intervention.

Plans for immediate emergent median sternotomy or thoracotomy in the event of hemorrhage or airway injury should be discussed during the preoperative time-out. All members of the nursing, circulating, and anesthesia teams must be aware of their roles in the event of an emergency situation.

To help ensure that all members of the operating room team are aware of what is happening surgically, video mediastinoscopy should be utilized so that all members of the surgery, anesthesia, and nursing teams can view the procedure simultaneously. However, video mediastinoscopy may not be feasible in all patients, as video mediastinoscopes, which are significantly larger than standard mediastinoscopes, may be too big to use in patients with limited space between the trachea and sternal notch and in patients with dense adhesions in this area. In these instances, a standard mediastinoscope must be used; therefore, both a video and standard mediastinoscope should be readily available. As only the surgeon is able to see the operative field with a standard mediastinoscope, proper communication is essential in the event of a complication.

Technical Aspects

Apart from issues of safety, studies have shown that video-assisted mediastinoscopy yields a higher number of lymph nodes than standard mediastinoscopy. However, owing to the larger size of the video instrument, video mediastinoscopy has been associated with slightly higher rates of recurrent nerve injury and pneumothorax. One recent report suggests that for patients with similar tumors, video mediastinoscopy not only yields a greater number of lymph nodes than standard mediastinoscopy but also far more frequently results in upstaging the disease. This results in fewer N2 false negatives undergoing surgery. The net effect is that patients who undergo video mediastinoscopy have better long-term survival than patients who undergo standard mediastinoscopy.

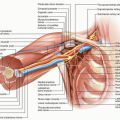

To successfully perform cervical mediastinoscopy, surgeons must know the anatomy of the innominate artery and vein, the aortic arch, the superior vena cava, the pulmonary artery, the azygous vein, the left recurrent nerve, the esophagus, and lymph node positions. Knowledge of this anatomy will result in an overall completion rate of 1%, including hemorrhage (0.3%), vocal cord dysfunction (0.5%), tracheal injury (0.01%), and pneumothorax (0.09%).4 Other rare complications include incisional metastasis and chyle leak.

Prior to incision, the thyroid isthmus and either the innominate or carotid artery should be palpated to detect any vascular anomalies. Aberrant innominate artery and right common carotid artery originating from a common carotid trunk have been described. The incision (2 to 4 cm) should be made below the thyroid isthmus and above the sternal notch. The incision is carried down to the pretracheal fascia. Finger dissection between the anterior trachea and the pretracheal fascia is extended to the tracheal bifurcation and laterally along both sides of the trachea. Finger dissection should be used to lift the innominate artery off of the trachea, and the pretracheal plane should be opened digitally to access the paratracheal nodes. These nodes can often be palpated in both the left and right paratracheal spaces. The use of finger dissection may be responsible for the low incidence of recurrent nerve injury following mediastinoscopy. In a review of patients in whom vocal cord motion was monitored during mediastinoscopy, digital dissection of the anterior tracheal wall activated both recurrent nerves. Cautery in the left paratracheal plane activated the left recurrent nerve, but cautery in the subcarinal or right paratracheal space elicited little activity in the right recurrent nerve. The study’s findings suggest that recurrent nerve injury is due to dissection and traction rather than cautery use.5

After the pretracheal plane has been opened, the mediastinoscope is inserted, and a suction dissector is used to open the subcarinal fascia.

After dissection has clearly revealed the lymph nodes in both the left and right paratracheal areas and in the subcarinal space, biopsy forceps can be used to sample these nodes. Several previous studies have reported that two to seven lymph nodes are sampled per procedure, but whether these studies were referencing individual nodes or pieces of nodes is unknown.6,7,8,9 Interestingly, one study demonstrated that the volume of tissue sampled from a lymph node station was correlated with the presence of N2 disease. This study showed that biopsy of a greater number of lymph node stations did not increase the chances of detecting N2 disease. The author concluded that the larger volumes were taken from enlarged suspicious nodes.10

Catastrophic bleeding can be avoided by the use of aspiration, prior to biopsy, if there is any doubt as to the dissection of a lymph node. Lymph node stations 2R, 2L, 4R, 4L, and 7 should be subject to biopsy. The aortopulmonary window lymph nodes (stations 5 and 6) cannot be biopsied during standard mediastinoscopy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree