Nipple discharge affects 5% to 30% of women during their lifetime. Surgery is rarely indicated. Many benign conditions cause nipple discharge, including duct ectasia, cystic disease, papillomas, infection, and abnormal production of prolactin. In addition, many medications can produce discharge. Discharges are usually categorized as physiologic or pathologic, depending on their color, frequency, and the involvement of single or multiple ducts. Those discharges that are bilateral, creamy or greenish in color, draining from multiple ducts, nonspontaneous, and associated with an otherwise normal physical exam and mammogram are rarely due to cancer or papillomas and do not require surgery except rarely for relief of symptoms. Clinical characteristics that suggest a pathologic discharge are unilateral discharge through a single duct; the presence of a bloody, clear, or serous discharge; discharge that is spontaneous; and those associated with a mass. Pathologic discharges usually require surgery to rule out a malignant cause, although cancer as a cause of nipple discharge is unusual.1-3 In a series of 204 patients presenting to a multidisciplinary group with nipple discharge, only 7 (3%) were found to have cancer or 9% of those ultimately referred for surgery.2 In a group of 82 patients referred to a surgical clinic with pathologic nipple discharge (spontaneous red or serous discharge from a single duct), 4 were found to have cancer (5%). Advanced age has been seen to be a predictor of cancer in women with nipple discharge.1,2

A patient presenting with a pathologic nipple discharge for evaluation should have a mammogram and physical examination.

A physical exam should include the usual palpation of the breast as well as looking for trigger points that elicit the discharge. This trigger point is often used to decide on location for the circumareolar incision. The nipple is carefully inspected for adenomas in the nipple as well as excoriations or skin changes that can lead to blood on the surface of the nipple. Excoriations from trauma, eczema, fungal rashes, and Paget disease can lead to blood staining of the bra, which patients can mistake for a nipple discharge.

The nipple discharge should be elicited to confirm the color, volume, and whether a single or multiple ducts are involved. The color should be distinguished by placing it on a white surface like gauze as the green-black discharge of duct ectasia is often mistaken for blood and these 2 discharges are treated differently. Yellow or green discharge from multiple ducts is usually a sign of duct ectasia and rarely requires surgery. The absence of blood on a guaiac card does not eliminate the possibility of a pathologic discharge,4 but its strong presence demands further evaluation. Any palpable mass should be needle biopsied. A nearby cyst can discharge into the nipple causing a serous discharge, and aspiration can halt the discharge. Similarly, infectious processes may discharge into the nipple and signs of infection should be treated with antibiotics and the patient reevaluated after the infection is cleared. Follow-up of these patients for recurrence of symptoms is essential, however, because an underlying cause like an obstructing papilloma or cancer may be present and usually will cause recurrence of the discharge. Sonogram may be helpful in these cases to identify an obstructing lesion.

Mass lesions, suspicious calcifications, or dilated retroareolar ducts may be seen on mammography in a patient with nipple discharge. Masses and calcifications can be stereotactically biopsied with a clip placed for preoperative localization and excision if atypia, papilloma, or cancer is seen. However, it is important to ensure that the abnormality identified is the cause of the discharge and not an incidental finding. Obviously, size and proximity to the nipple are important in making this decision.

If both physical exam and mammogram are found to be normal, various approaches have been suggested as preoperative evaluation.

Many investigators use routine retroareolar sonography in conjunction with mammography for preoperative evaluation.2,5,6 The ability of ultrasound to visualize the causative lesion ranges from 26% to 69%2,5-7 and is clearly operator dependent. Rissanen et al reported on 52 patients with bloody or serous discharge who underwent both galactography and sonography prior to surgery.5 In 69% of patients, an intraductal lesion was seen on sonography, identifying 65% of papillomas but only 1 of 5 malignant lesions. Dilated ducts were seen in 3 of 5 cases with malignant lesions, and in 1 the sonogram was normal. Sonography identified 2 tumors not identified by galactography. Gray et al reported on 204 patients presenting to a multispecialty group practice with true nipple discharge.2 Sonography was performed in 142 patients and a mass was identified in 30 (21%). Among 7 patients (3%) ultimately diagnosed with cancer, 6 had a preoperative sonogram, 5 of which identified the malignancy preoperatively. However, sonography had a low specificity in this series as in others. In a study from MD Anderson, 64 patients with pathologic discharge undergoing surgery had a sonogram; 13 sonograms showed a suspicious mass and 18 showed duct ectasia.8 Among 19 patients ultimately found to have cancer, the sonogram was abnormal in 12; 7 showed suspicious masses and 5 showed duct ectasia. While there are false-negative sonograms in all series, sonography is inexpensive, noninvasive, and widely available, and if a lesion is found, it can be percutaneously biopsied or sonographically localized the day of surgery. Vargas et al recommend percutaneous biopsy of any lesion found sonographically and surgical duct excision for those with no imaging findings.6

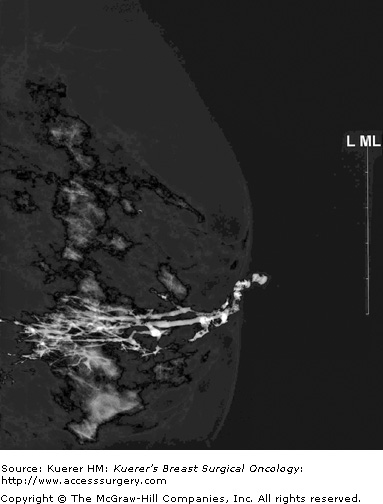

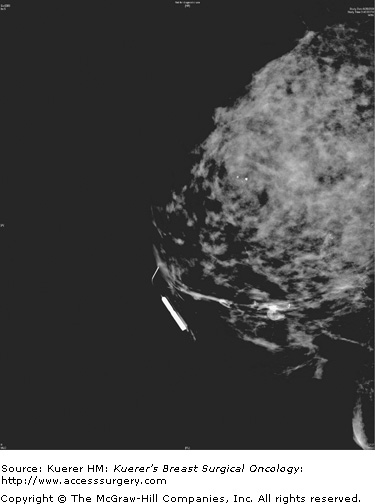

Ductography, a radiologic examination, has the potential to pinpoint the offending lesion in the major duct that is causing the discharge, thereby aiding in diagnosis, limiting the extent of surgical resection, and making it more likely the pathologic lesion will be removed.8,9 The discharging duct is cannulated with a small (30-gauge) catheter, and at this point the duct can be aspirated or lavaged to obtain a cytologic specimen. The duct is then injected with water-soluble contrast until the patient experiences discomfort or the contrast flow is reversed. Mammograms are then taken in craniocaudal (cc) and lateral views and any other views as necessary to demonstrate the intraductal pathology.10 Cutoff of the duct, filling defects, or duct ectasia are considered abnormal (Figs. 57-1 and 57-2). Repeating the ductogram on the day of surgery, with injection of methylene blue dye and in conjunction with preoperative wire localization, may allow for a limited surgical duct excision and preservation of a patient’s ability to breast-feed, while ensuring that the responsible lesion is removed.

Possible difficulties encountered during ductography may be that the discharge is not able to be produced at the time of the exam, the occasional inability to cannulate the offending duct because of small size, the cannulation of the wrong duct, perforation of the duct with extravasation of contrast, or the introduction of air bubbles that can mimic intraductal lesions.

In a review of duct excisions at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Van Zee et al reported on 46 duct excisions of which 21 had preoperative ductography.9 Sixteen of these excisions were performed with preoperative ductography repeated the morning of surgery, with methylene blue in most, and in 4 with lesions distant from the nipple a localizing wire was placed. In these 21 duct excisions, a papilloma or cancer was found in 17 (81%) patients. This is in contrast to the 30 patients who did not undergo preoperative ductography and whose surgery was performed as a total duct excision without guidance. In this group, papillomas or cancer was found in 13 (43%), duct ectasia in an additional 7 (23%), and no cause for the discharge was found in 10 (33%) patients.

In a similar evaluation of all patients undergoing ductography at Baylor between 1995 and 1998, Lamont et al reported on 35 patients of which abnormalities were detected in 30.11 Twenty-seven of the 30 had excision, either by total duct excision (14/27), focused duct excision (12/27), or mammotome (1/27). All patients were found to have a pathologic cause for the discharge; 20 patients were found to have a papilloma, 1 of whom also had ductal carcinoma in situ; and 7 had duct ectasia. Among 5 patients with normal ductograms, 2 had surgery, 1 was found to have a papilloma, and 1 had duct ectasia. The other 3 were followed and none of these was found to develop cancer; the follow-up period was not stated in this paper. In a study of 42 patients with pathologic discharge in whom 21 had ductograms, 14 were reported as abnormal.12 Twenty percent of ductograms showed a lesion greater than 3 cm from the nipple. Six of 14 abnormal ductograms showed multiple lesions, some of which were localized by needle preoperatively. In these cases, ductography was instrumental in removing lesions that might have not been included in a total duct excision without localization. On the other hand, 4 patients with normal ductograms had papillomas found at surgery. This may be due to injecting the wrong duct, a pitfall of ductography. The authors conclude that a normal ductogram does not preclude a duct excision. In a study of 94 patients undergoing surgery for pathologic discharge, Cabioglu et al demonstrated that with the exception of an abnormal mammography or sonography to guide excision, a ductography-guided operation had a higher likelihood of finding a pathologic correlate for the nipple discharge compared to lacrimal probe guidance or central duct excision.8