Carcinoma of the Vulva

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

Vulva

The vulva is composed of the mons pubis, clitoris, labia majora and minora, vaginal vestibule, and their supporting subcutaneous tissues. The vulva blends with the urinary meatus anteriorly and with the perineum and anus posteriorly. The mons pubis consists of prominent tissue located anteriorly to the pubic symphysis. The labia majora are two elongated skin folds that course posteriorly from the mons pubis and blend into the perineal body. The skin of the labia majora is pigmented and contains hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The labia minora are a smaller pair of skin folds located between the labia majora. Anteriorly the labia minora separates into two components that course above and below the clitoris, fusing with those of the opposite side to form the prepuce and frenulum, respectively. The skin of the labia minora contains numerous sebaceous glands but no hair follicles and has no underlying adipose tissue. The clitoris is 2 to 3 cm anterior to the urethral meatus and is supported externally by the fusion of the labia minora.

The vaginal introitus is demarcated laterally by the labia minora and posteriorly by the perineal body. Anteriorly numerous small vestibular glands are located beneath the mucosa and open onto its surface adjacent to the urethral meatus. The Bartholin’s glands (or greater vestibular glands) are two small mucous-secreting glands situated within the subcutaneous tissue in the posterior aspect of the labia majora. The ducts of the Bartholin’s glands open onto the posterolateral portion of the introitus. The Skene’s glands (or paraurethral glands) open in the anterior aspect of the introitus but can be variable in location. The perineal body is a 3- to 4-cm band of skin that separates the vaginal introitus from the anus and forms the posterior margin of the vulva with the fusion of the labia minora, or the fourchette.

Lymphatic Drainage

The inguinofemoral nodes are located within the triangle formed by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the border of the sartorius muscle laterally, and the border of the adductor longus muscle medially. There are superficial inguinal lymph nodes that lie along the saphenous vein and its branches between Camper’s fascia and the cribriform fascia overlying the femoral vessels. There are usually three to five deep nodes, the most superior of which is located under the inguinal ligament and is known as Cloquet’s node. Lymph drains from these nodes into the external and common iliac pelvic lymph nodes.

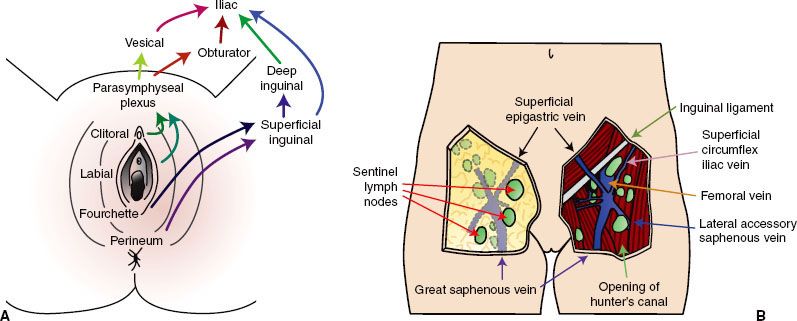

Lymphatic drainage is specific to the location of a vulvar lesion. Labial lesions drain into the superficial inguinal and femoral lymph nodes, then penetrate the cribriform fascia and reach the deep femoral nodes. Lesions of the fourchette and perineum follow the lymphatics of the labia. Lymphatic drainage from the glans clitoris or perineal body enter either unilateral or bilateral superficial femoral nodes or the deep femoral and pelvic lymph nodes. Some lymphatics originating in the clitoris enter the pelvis directly, bypassing the femoral nodes to connect with the obturator and external iliac lymph nodes, though in practice, the pelvic lymph nodes are rarely involved without synchronous involvement of the inguinal nodes (Fig. 74.1).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Vulvar cancer is a rare malignancy that represents < 1% of all the cancers diagnosed in women and <5% of all gynecologic neoplasms. In the United States, it is estimated that there were 3,900 new cases in 2010, with 920 deaths due to the disease.1 The incidence is 2 cases per 100,000 women; however, this incidence increases to 13 per 100,000 in women of age >75 years.2 The incidence is slightly lower in Black women (1.6 per 100,000) and Hispanics (1.5 per 100,000) compared with Whites (2.4 per 100,000), and Asians/Pacific Islanders have the lowest incidence (0.9 per 100,000).

There are two primary mechanisms believed to be involved in the carcinogenesis of this disease: human papillomavirus (HPV) and vulvar dystrophy, including lichen sclerosus and squamous hyperplasia. HPV DNA can be identified in 40% of invasive vulvar cancers, with 16, 18, and 33 being the predominant subtypes.3,4 This is in contrast to vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), from which HPV can be isolated in 70% to 90% of lesions.5 Because HPV infection is related to numerous other cancers of the anogenital region (e.g., cervical cancer and anal canal cancer), the risk factors are similar: previous diagnosis of genital warts, multiple sexual partners, smoking history, previous abnormal Papanicolaou test, and immune suppression.6,7 Lichen sclerosus (LS) has been found to be associated with vulvar cancer in 30% to 60% of cases in some series,8,9 although there is no histopathologic evidence of direct transformation.10 Women with existing LS have a 5% risk of developing invasive disease.11 The evidence for VIN as an obligate precursor to invasive vulvar disease is much less compelling than that established between cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. Only one-third of vulvar cancers have an associated VIN-3 lesion,12 and <5% of women with an existing VIN lesion will subsequently be diagnosed with invasive disease.13,14

These findings have led to the hypothesis that squamous carcinoma of the vulvar can be broadly classified into two clinicopathologic entities: keratinizing squamous carcinomas (KSCs) and basaloid squamous carcinomas (BSCs).15 KSC is more common (80% of cases), is found in older women with vulvar dystrophy, and is rarely associated with other neoplasia, HPV, or VIN.16 p53 may or may not stain positive in KSC, because p53 mutations may play a role in pathogenesis in a subset of these neoplasms; p16 is rarely positive.17 BSC, in contrast, is less common (20% of cases), is found in younger women, and is associated with multifocality, other anogenital neoplasia, HPV infection, and VIN. In BSC, staining for p53 is often negative, whereas p16 is often positive due to HPV infection.

FIGURE 74.1. A: The lymphatic drainage of the vulva initially flows to the superficial inguinal nodes and then to the deep femoral and iliac group. Drainage from midline structures may flow directly beneath the symphysis to the pelvic nodes. (Modified from Plentl AA, Friedman EA, eds. Lymphatic system of the female genitalia. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1971.) B: The superficial inguinal lymph nodes comprise 8 to 10 subcutaneous nodes located between Camper’s fascia and the cribriform fascia. These nodes are immediately adjacent to the saphenous vein and its branches. (Modified from DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT, Rich WM. An alternative approach to early cancer of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1979;133:825.)

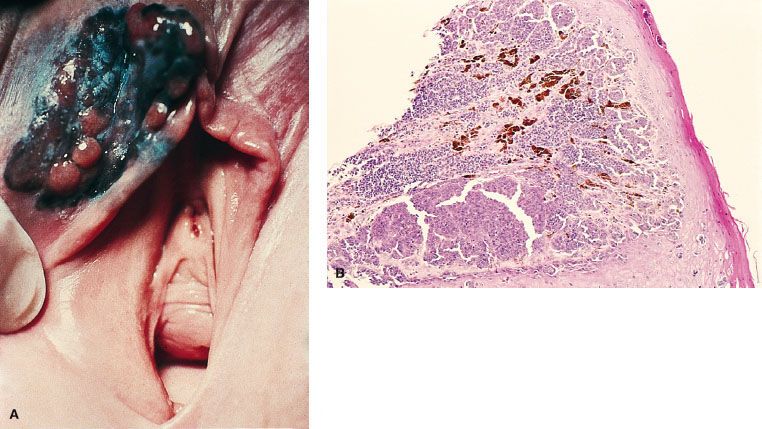

FIGURE 74.2. Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. A: Squamous cell carcinoma with ulceration, arising from the right labia minora. This elderly woman had no apparent predisposing disease. B: Photomicrograph of invasive keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Note the keratin pearls. (Courtesy of Dr. Stanley Robboy, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.)

PATHOLOGY

PATHOLOGY

Squamous Carcinoma

Eighty-five percent of invasive disease of the vulva is squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 74.2).18 As noted earlier, these arise within squamous epithelium, often in or adjacent to areas of epithelial abnormalities or of premalignant conditions such as lichen sclerosus, erythroplasia of Queyrat, and Bowen’s disease.19 The depth of invasion, critical for appropriate staging and management, is defined as the distance from the epithelial stromal junction of the most superficial adjacent dermal papillae to the deepest point of invasion. Tumor thickness is measured from the overlying surface epithelium, or the bottom of the granular layer if the surface is keratinized, to the deepest point of invasion as specified by the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists.20

There are three recognizable types of growth pattern of squamous carcinoma: confluent, compact, and spray or finger-like growth. Confluent growth is defined as a tumor mass composed of interconnected tumor >1 mm in dimension. This type of growth is characteristic for being deeply invasive with associated stromal desmoplasia. Compact growth is associated with well-differentiated tumors, which maintain continuity with the overlying epithelium, infiltrating as a well-defined and circumscribed tumor mass, which rarely invades the vascular space. Histologically, the tumor cells resemble squamous cells of adjacent and overlaying epithelium. The spray or finger-like growth pattern is characterized by a trabecular appearance with small islands of poorly differentiated tumor cells found within the dermis or submucosa, deeper than the main tumor mass. This growth pattern is often associated with desmoplastic stromal response and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Vascular space involvement is seen more commonly with this pattern of growth than with tumors with a compact pattern of growth.21

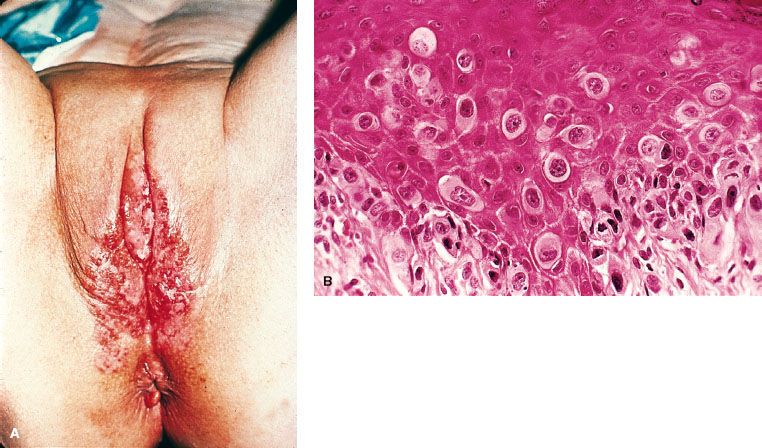

FIGURE 74.3. Melanoma of the vulva. A: A nodular, elevated, and darkly pigmented lesion arising from the right labia majora. B: Photomicrograph of invasive melanoma, with melanin apparent in portions of the tumor. (Courtesy of Dr. Stanley Robboy, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.)

Uncommon Histologic Types

Malignant melanoma of the vulva accounts for approximately 10% of all primary tumors of the vulva, occurs predominately in White women, and has a peak incidence in the sixth and seventh decades (Fig. 74.3).22 Sometimes the tumor arises in a pre-existing pigmented lesion, and in these cases the differential diagnosis includes benign vulvar melanosis and pigmented VIN. Vulvar melanomas can be subclassified into three specific categories: superficial spreading malignant melanoma; nodular melanoma; and acral lentiginous melanoma.23 As is the case for melanomas arising in other sites, the level of invasion and tumor thickness dictate the therapy and determine the prognosis.24

Adenocarcinomas of the vulva arise predominantly in the Bartholin’s glands, although apocrine, eccrine, and Skene’s glands can also be the site of origin. In the rare instances when adenocarcinomas arise in the absence of glandular tissue, they may be of cloacogenic origin. Carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is seen more frequently in older women and is often solid and deeply infiltrative. The overlying epidermis may remain intact, leading to misinterpretation as a benign process. Other histopathologic types are mucinous, papillary, mucoepidermoid, adenosquamous, and transitional. The transition from normal to malignant glandular tissue can be recognized in some cases. Adenocarcinomas often present with more locally advanced disease with metastases to the inguinal-femoral lymph nodes.

Paget’s disease of the vulva (intraepithelial adenocarcinoma) is seen most often in postmenopausal, older White women. The disease varies in appearance, but most often it presents as an eczematoid, red can or weeping lesion, and it can be mistakenly diagnosed as eczema or contact dermatitis (Fig. 74.4). The lesion may be flat, raised, or ulcerated and may appear whitish (leukoplakia), red (erythroplastic), or hyperpigmented. This condition has a typical histologic pattern and often stains positive for carcinoembryonic antigen. Vulvar Paget’s disease is associated with invasive carcinoma in 10% to 20% of the cases.25,26,27 The invasive disease may be an underlying adenocarcinoma of the apocrine or Bartholin’s glands, or it may be an adenocarcinoma arising elsewhere in the anogenital region.

Verrucous carcinomas of the vulva are uncommon, usually diagnosed in the fifth or sixth decade of life. Histologically these tumors are often well differentiated and have a low incidence of metastasis to the lymph node. In instances when the lesion is in early stage, excellent results are obtained with radical wide excision.28 Other vulvar malignancies arising from epidermal cell types are rare. Merkel cell tumors (neuroendocrine carcinomas) of the vulva are aggressive locally, have a high incidence of distant metastasis, and carry a poor prognosis. Basal cell carcinomas, on the other hand, seldom spread to lymph nodes and are appropriately treated with wide excision alone.29 Transitional cell carcinomas may arise from the Bartholin’s glands or may also represent metastasis from the bladder and/or lower urinary tract.

The most common subtypes of vulvar sarcoma are leiomyosarcomas, malignant fibrous histocytomas, epithelioid sarcomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas. Rhabdomyosarcomas of the vulva require combination therapy, chemotherapy, and radiation, as per rhabdomyosarcoma protocols of other sites. Results of treatment with other sarcomas of the vulva are unpredictable, and wide resection and/or radical radiotherapy should be considered, given the relative inactivity of chemotherapy.

FIGURE 74.4. Paget’s disease of the vulva. A: Photo of extensive perineal disease, extending to the perianal skin. B: Photomicrograph of intraepithelial Paget cells, with copious pale cytoplasm, occurring singly or in small clusters, and appearing slightly larger than neighboring squamous cells. (Courtesy of Dr. Stanley Robboy, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.)

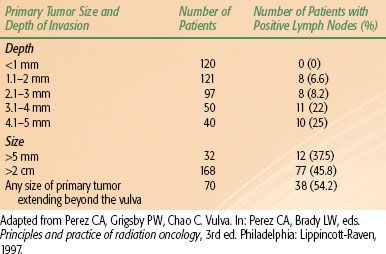

TABLE 74.1 INCIDENCE OF LYMPH NODE INVOLVEMENT CORRELATED WITH PRIMARY TUMOR SIZE AND EXTENT

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Vulvar pruritus is the most common presenting symptom, although women may also complain of bleeding, pain, or discharge. If there is a visible lesion on physical examination, a biopsy is required to distinguish it from other vulvar lesions such as dystrophia, benign condylomata, and VIN. Unfortunately, many women have a long delay in diagnosis due to denial or minimization of symptoms and may present with a locally advanced tumor by the time of initial evaluation. These lesions may also present with symptoms related to the invasion of regional structures, including difficulty with urination or defecation. Metastatic disease is an uncommon presenting symptom because the primary lesion is usually much more problematic, although consequences of groin and distant disease may also be seen at presentation.

PATTERNS OF DISEASE AND SPREAD

PATTERNS OF DISEASE AND SPREAD

Primary Site

Approximately 70% of vulvar malignancies arise in the labia majora and minora, 15% in the clitoris, 5% in the perineum and fourchette, 5% in the prepuce Bartholin’s glands and urethra, and 5% are too extensive at presentation to classify.30

Lymphatic Spread

High-grade tumors with “spray” growth pattern and lymphatic space invasion have a proclivity to spread to the regional lymphatic nodes. The superficial inguinofemoral lymph nodes are the first echelon, followed by the deep inguinofemoral nodes. For well-lateralized lesions, metastasis to the contralateral inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes is unusual in the absence of ipsilateral inguinofemoral node involvement. Lesions of the clitoris or urethra can spread directly to pelvic lymph nodes, although this is rare without involvement of the inguinal nodes.31,32

The frequency of inguinal lymph node metastasis in surgically staged patients ranges from 6% to 50%, depending on tumor invasion and extent of disease (Table 74.1).33–37 Physical examination alone is inaccurate to assess lymph node involvement: Plentl and Friedman30 reported a 62% incidence of lymph node metastases in patients with clinically palpable adenopathy and 35% involvement in patients without clinically palpable adenopathy. In a review of clinical staging, Franklin38 noted that approximately 75% of patients with clinically suspicious lymph nodes had nodal metastasis, and 11% to 43% of patients with clinically negative nodes had metastasis to the nodes. In a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study reported by Homesley et al.39 23.9% of the patients with clinically negative inguinal nodes were found to have nodal metastasis on final pathology. When the lymph nodes were clinically suspicious, 76.2% of the patients had histologically positive nodes. In patients that have histologically positive inguinal nodes, the probability of having positive pelvic nodes is 30%.39

Multiple clinical and histologic features of the primary tumor are associated with nodal metastasis, including tumor thickness, histologic grade, capillary-like space involvement, depth of invasion, location of the tumor, and tumor size.40,41 Rutledge et al.42 also described the adverse effect on local control and survival of tumor size, clinical stage, positive inguinal or pelvic nodes, and positive margins at the primary site. When the tumor thickness is ≤1 mm, the probability of nodal metastasis is ≤3%, but with tumor a tumor thickness ≥5 mm, the probability increases to 33.3%. Depth of invasion of 1, 2, and 3 mm corresponds to a 4.3%, 7.8%, and 17% incidence of nodal involvement, respectively. It should be noted that in the vulva the thickness of the epithelium varies significantly from one area to another, in some areas being >0.8 mm thick, which can influence the relative value given to tumor thickness and depth of invasion. Measuring tumor thickness in superficially ulcerated tumors can be misleading and may lead to underestimating the depth of invasion. Perineural invasion correlates strongly with lymph node metastasis.43

In analysis of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) database on carcinoma of the vulva, several clinical and histologic tumor characteristics were identified as predictors of nodal involvement. In order of importance these are clinical node status (palpable vs. nonpalpable), grade, capillary-lymphatic space involvement, tumor thickness, and patient’s age.39,41,44 There is also a correlation between the size of the primary tumor and involvement of the lymph nodes. In Donaldson et al.’s34 series of 66 patients, the probability of having positive inguinal nodes rose from 18.9% for patients with lesions <3 cm to 72.4% for patients with primary tumors ≥3 cm. In a GOG study of 267 patients with superficial vulvar cancer reported by Sedlis et al.,41 the frequency of positive inguinal nodes was 18.1% for patients with lesions up to 3 cm in size and 29.3% for patients with lesions ≥3 cm. Extension of the primary tumor to the urethra, vagina, and anal area is associated with an increased incidence of nodal involvement and worsening of prognosis. The significance of this is reflected in the stage assignment of the patients.

Curry et al.45 noted that pelvic nodes were not involved if three or fewer inguinal nodes were positive. Similar findings have been reported by Hacker et al.46 In the GOG study reported by Homesley et al.47 of patients with positive inguinal nodes, the incidence of pelvic node involvement was 28.3% (15 of 23). In this study, there was a correlation of pelvic node involvement with the extent of inguinal node involvement. Due to the rarity of isolated pelvic nodal metastasis, the status of the inguinal nodes determines the management of the pelvic nodes. Although deep pelvic node involvement is an ominous sign, one-fourth to one-third of the patients are still potentially curable, particularly if only a few nodes are involved.31,33,45

Distant Metastases

Hematogenous dissemination generally occurs late in the natural history of the disease, with the most common sites being the lungs, liver, and bones. The development of distant metastasis portends a very poor outlook.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Lymph node metastasis is the most important prognostic factor in patients with vulvar cancer. The presence of inguinal node metastases is accompanied by a 50% reduction in long-term survival.48,49 Pelvic nodal metastasis has an even more profound negative effect on survival.31,33,45 Kurzl and Masserer50 analyzed 124 patients with various stages of vulvar carcinoma treated with simple vulvectomy alone and local/inguinal irradiation. They found that age, disassociated growth, lymphatic spread, thickness, and ulceration of the primary tumor were important prognostic factors. In a detailed analysis of a GOG clinicopathologic study of 558 women with vulvar cancer, two significant risk factors were identified that predispose for recurrence in the vulva: tumor size >4 cm and capillary lymphatic space involvement.44 If either of these factors was present, the risk of local recurrence after radical vulvectomy was 20.7% (30 of 184), but if neither factor was present, the risk of local recurrence was only 9.2% (37 of 404). In this study the depth of invasion did not predict for vulvar failure.

In an analysis of formalin-fixed tissue specimens, Heaps et al.51 demonstrated a sharp rise in the incidence of local recurrence for tumors with microscopic, surgical margins <8 mm. They suggested that this would correspond to a minimum margin of 1 cm in fresh, unfixed tissue. Although the frequency of local recurrences correlates with the adequacy of the margins of the surgical resection, when dealing with larger or thicker tumors or when they involve midline structures, adequate surgical margins may be difficult to obtain.

Lymph node extracapsular tumor extension has been noted in several series and it is known to have a negative effect on prognosis. Origoni et al.52 evaluated the significance of the size of the metastases in the lymph nodes, the number of positive lymph nodes, and extracapsular extension of the disease and found that the presence of any one of these factors worsened the prognosis. Extracapsular tumor extension as an independent adverse prognostic factor on survival was also described by van der Velden et al.53

INITIAL EVALUATION

INITIAL EVALUATION

A thorough examination of the genitourinary system is warranted in all women with vulvar cancer because the disease may be multifocal. Examination of the vagina, cervix, perianal skin, and anal canal is of particular importance in order to delineate the extent of disease and to identify synchronous lesions. Special attention as well is paid to the inguinofemoral basins for clinical detection of lymphatic spread.

Imaging studies may not be necessary in early lesions that may be approached with surgery as the first treatment modality. However, imaging in women with locally advanced disease or with clinically suspicious lymph nodes may aid the clinician in selecting the most appropriate treatment. Computed tomography (CT) scans may identify concerning lymphadenopathy in the inguinofemoral chains, pelvis, or para-aortic regions.54 Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also aid in the delineation of the primary lesion, as well as with the evaluation of inguinal lymph nodes, with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 88%.55 Although clinically or radiographically detected inguinal nodes may be quickly evaluated with ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration, a negative result does not rule out involvement.56 Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography has been used to evaluate the groin prior to surgical evaluation, with a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 95%.57 It should be noted that the sensitivity of all imaging modalities available are insufficient to omit surgical evaluation in women with a high risk of nodal involvement.

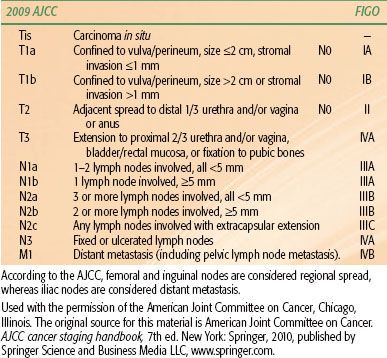

TABLE 74.2 VULVAR CANCER: 2009 AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE ON CANCER (AJCC) STAGING AND CORRESPONDING INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS (FIGO) STAGING

STAGING

STAGING

The staging system first adopted in 1983 was based on clinical findings. The system was modified in 1988 to give the clinical status of the nodes more importance. In 1997 the staging was revised again to create a separate category for minimally invasive lesions, stage IA, emphasizing the need for histologic assessment of the inguinal nodes in all patients presenting with primary tumors with >1 mm depth of invasion.

The most recent Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging revision was performed in 2009 and contains significant changes from the 1988 framework (Table 74.2).58,59 Stage IB now includes primary lesions >2 cm in size (previously stage II), and stage II includes lesions with involvement of adjacent perineal structures (previously stage III). Stage III is now divided into three substages, reflecting the importance of the number and size of inguinal nodes involved and the prognostic significance of extracapsular extension. Presence of pelvic nodal metastases remains stage IVB disease.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

The treatment of carcinoma of the vulva is challenging for multiple reasons. In general patients with this disease are older and have comorbidities. The tumor, by virtue of its location, can easily involve adjacent organs such as the bladder and the rectum, and the frequency of nodal involvement is high. Because of its relatively low incidence, most published reports include rather small and heterogeneous groups of patients. Management of carcinoma of the vulva is further complicated by the major psychosexual impact that the treatment can have on patients. For the aforementioned reasons it has been difficult to study this disease and to develop treatment guidelines.

The management of vulvar carcinoma has undergone very significant changes in the last few decades. En bloc resection of the primary tumor and inguinal node dissection, which used to be the standard of care, have been replaced by multimodality therapy, with the surgery being more tailored to the extent of the disease. This change follows the recognition of the morbidity associated with radical surgery, the improved results achieved with multimodality therapy, and the recognition of the negative impact that radical surgery can have on sexual function and body image.6,60,61 Although radical surgery retains a very important place in the management of vulvar cancer, it is no longer the mainstay of the treatment. The likelihood of controlling the primary tumor with surgery largely depends on the adequacy of the margins of resection, and it is not necessary to remove the entire vulva. A clear margin of about 1 cm in all directions is sufficient to achieve a high rate of local control of the primary tumor.51

There have been refinements in the surgical technique that have made the procedures more tolerable. Examples of such improvements include primary closure of the perineal wound, the use of the sartorius muscle to close the surgical defect in the inguinal area, and the use of separate incisions for the resection of the primary tumor and the inguinal nodes. These developments have resulted in a decrease in operative mortality and morbidity.

In recent decades there have been also significant advances in all aspects of radiation therapy that apply to the treatment of carcinoma of the vulva. The technical resources available now make it possible to deliver effective doses of radiation to the vulvovaginal and inguinal regions with less acute and late morbidity. With high-photon-energy units, well-collimated fields, multileaf collimators, electron beams of different energies, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), radiation is now delivered to the primary disease and lymph nodes with precise account of the differences in contour, tissue thickness, and extent of the disease. It is possible to tailor the treatment to the specified treatment volume while keeping the dose to the normal tissues within acceptable limits of tolerance. Brachytherapy may also be used as primary treatment in very selected cases or in combination with external beam to bring the dose higher to limited volumes.

Perhaps the most significant advance of recent decades in the management of cancer patients is the use of more than one treatment modality concurrently or sequentially. Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery in sequence and/or in combination lessen the impact of any one modality and can achieve functional organ preservation with at least comparable or improved local tumor control and survival (Fig. 74.5).

Early Invasive Disease

Surgery

In the past even patients with early stage IB disease were considered to have diffuse disease, and a radical vulvectomy was considered the standard of care, yielding 90% survival rates but with considerable physical and emotional sequelae.51,62 Now, small, favorable lesions, ≤2 cm in diameter and ≤5 mm in depth, are managed with wide, local excision rather than a radical vulvectomy, with very satisfactory outcomes in every respect. The local recurrence and disease survival rates are similar with either procedure, ranging from 6% to 7% and 98% to 99%, respectively.63 However, anterior lesions close to the clitoris may not be amenable to wide local excision and may require a radical vulvectomy to obtain satisfactory margins.

Small, well-lateralized, T1 lesions with negative ipsilateral groin nodes have <1% risk of contralateral groin involvement, and treatment of the contralateral groin is not necessary.63 Poorly differentiated tumors, with >5-mm invasion and vascular space involvement, are at higher risk for inguinal node metastasis, and both groins must be evaluated and managed as needed.39 Centrally located lesions, within 1 cm of the introitus, are considered midline lesions and may be treated with local excision, if possible, but both groins are at risk. A deep node dissection is recommended if the superficial nodes are involved. Traditionally, primary tumors >2 cm have been treated with radical vulvectomy and bilateral groin dissection because of the high risk of nodal involvement. The indications and extent of surgery for the inguinal nodes are under re-evaluation and are the subject of further discussion later in this chapter.

FIGURE 74.5. Treatment algorithm.