Cancer survivorship: new challenge in cancer medicine

Julia H. Rowland, PhD

Overview

As the population of cancer survivors continues to increase, so too has attention to the long-term care needs of these individuals after treatment ends. While most survivors adapt well post-treatment, many experience lingering effects of their illness. In some cases, these effects become permanent and raise challenges to recovery and adaptation. In this chapter, we outline some of the common persistent sequelae of cancer and their management and review the emerging guidelines for survivorship care planning. Models of follow-up care after cancer are discussed, along with the needs and support of informal cancer caregivers in this process. Recommendations for future directions in survivorship research and care are provided.

Introduction

A quick glance through the chapters of the ninth edition of this classic volume reveals how very far we have come in advancing the science and art of cancer medicine. Arguably, the greatest measure of the progress made is the growing population of cancer survivors. While a testament to the many successes achieved, this population is at the same time a reminder that a focus on cure is not enough; we must attend equally to the life to which we return each patient treated. How best to care for patients after primary treatment ends and there is no evidence of disease, is one of the emerging challenges for healthcare providers.

In this chapter, we will review the magnitude of the challenge clinicians—along with cancer survivors themselves and their loved ones—face after cancer. Survivors of childhood cancer have been at the vanguard of the survivorship movement in the United States, in part because of the truly dramatic progress made in curing cancers in this youngest population. The special challenges to and guidelines for their long-term care are well detailed elsewhere.1–8 In this chapter, we will restrict our review to the post-treatment recovery and care of individuals diagnosed as adults.

Cancer survivorship: a brief history

Before the 1970s, the picture for most patients diagnosed with cancer was bleak. There were few effective treatment options, and most entailed serious adverse effects that were often poorly controlled.9, 10 In this earlier period, a major focus was on helping people die of their disease, not live with it. The “survivors” in this earlier period were more often grieving family members than patients themselves. As our ability expanded to both cure and control the many diseases we call cancer, this picture changed dramatically.

The origins of the survivorship movement are often attributed to two events. The first was the publication in 1985 in the New England Journal of Medicine of a piece by a young physician, Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan, entitled “Seasons of Survival.”11 In this commentary, Mullan describes his personal experience with cancer and provided, for the first time, language for thinking about an expanded cancer trajectory. The following year, a group of 23 individuals, including Mullan, gathered in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and founded what is now known as the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS). This group proposed a new definition of the term “cancer survivor.” Until then, the term “cancer survivor” referred to someone who had remained disease-free for a minimum of 5 years. The coalition members argued that a “cancer survivor” should refer to anyone with cancer, from the moment of diagnosis and for the balance of his or her life. The intent of the NCCS founders was not to label individuals. Rather, they wanted first to convey a message of hope to those newly diagnosed with cancer that life was not over, and second, to promote a dialogue between patients and their physicians about the impact that different treatment options might have on survivors’ future health and functioning (i.e., to foster informed, patient-centered decision making). Although some persons with a cancer history do not consider themselves to be survivors,12, 13 the language helped launch a survivorship movement globally.

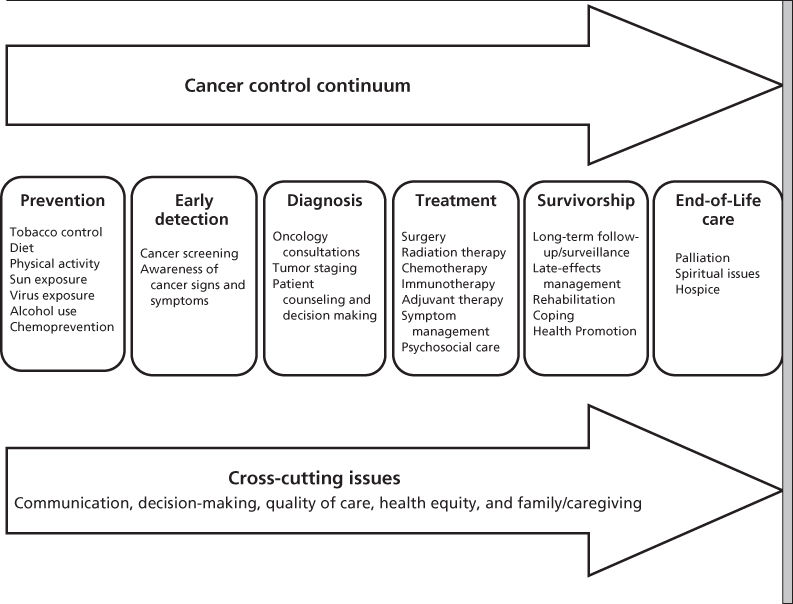

Since 1986, the field of cancer survivorship has come into its own. The past dozen years in particular have seen national attention paid to the topic of cancer survivorship. This is reflected in the publication of five major reports addressing the status of the research and care of those living with cancer, including two volumes produced by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) on childhood1 and adult cancer survivorship,14 a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Lance Armstrong Foundation calling for a national action plan around cancer survivorship,15 and two reports from the President’s Cancer Panel.16, 17 Major noncancer and cancer scientific journals have devoted special issues to this aspect of the cancer control continuum,18–21 texts have appeared summarizing our accomplishments in the field of survivorship research and promoting evidence-based care,22, 23 and the field now has a scientific journal dedicated to this burgeoning area of science.24 Importantly, cancer survivorship is recognized to represent a discrete place on the cancer control continuum, bringing its own unique set of concerns and challenges. The key driver behind attention to this field has been the sheer numbers (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cancer control continuum—elaborated.

Source: Adapted from http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/od/continuum.html.

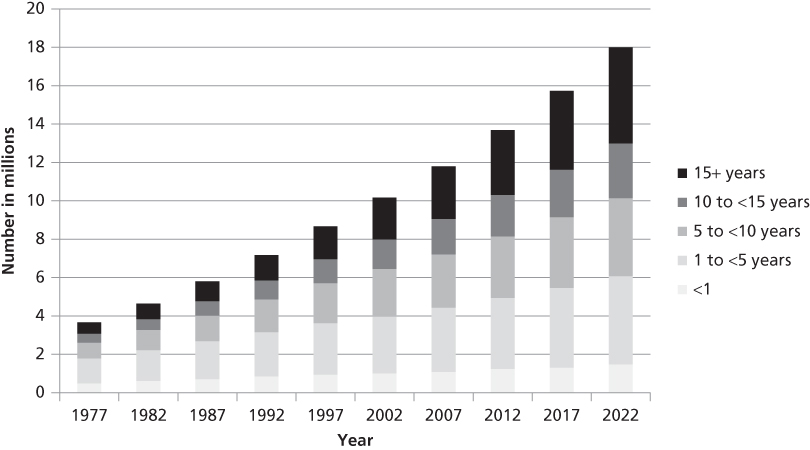

Figure 2 Estimated and projected number of cancer survivors in the United States from 1977 to 2022 by years since diagnosis.

Source: de Moor 2013.27

Magnitude of the problem

Cancer prevalence

As of January 1, 2014, there were an estimated 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States alone.25 Globally, figures suggest that there are over 32.6 million cancer survivors worldwide, although this represents a minimum count as most countries can only project prevalence up to 5 years post diagnosis.26 As reflected in Figure 2, the number of cancer survivors has increased steadily over the past 45 years. In 1971, when President Nixon signed the National Cancer Act and declared the “war on cancer,” there were an estimated three million survivors. By 2024, this number will climb to 19 million. The increase in numbers is due in part to advances in early detection, treatment efficacy, and supportive care. Breakthrough discoveries notwithstanding, however, the biggest contributor to growth in cancer prevalence in the decade to come will be the aging of the population.28

Today, over 60% of those diagnosed are aged 65 and older. With the Baby Boomer generation turning 65 at a rate of approximately 11,000 a day (since January 2011), it is estimated that 11 million cancer survivors will be older adults by 2020, representing a 42% increase in their numbers in just one decade (2010–2020).29

In addition to their growing numbers, today’s cancer survivors are also living longer. In 2014, 41% of survivors were diagnosed 10 or more years ago, and an impressive 15% were diagnosed 20 or more years earlier (Figure 2).27 Healthy People 2020 has a target goal to increase the proportion of cancer survivors who are living 5 years or longer after cancer to 72.8%.30 While we have surpassed this figure for those diagnosed as children (age <15), where 10-year survival is now >77%, this is definitely a challenge goal in adult onset cancers. Approximately 68% of adults diagnosed today can expect to be alive in 5 years. Unknown in all of these figures is the well-being or disease status of this burgeoning population. Beyond estimates for the number of individuals within 1 year of diagnosis, and 1-year from death, our Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry data provide limited information about the health status of the cancer survivor population. This constitutes an important gap in our knowledge base. Of note, Healthy People 2020 also has a goal to increase the mental and physical health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of cancer survivors.30 How we are to measure this effect remains unclear.

Cancer’s long-term and late effects

Research among long-term cancer survivors has grown in parallel to their growing numbers. Clear from this science and the testimony of survivors themselves is that being told you are cancer-free does not mean you are free of the cancer experience. As one survivor put it, “It’s not over when it is over.”

Cancer has the capacity to affect virtually every aspect of an individual’s life and function: physical, psychological, social, economic, and existential (Table 1). Some of these effects are acute and resolve quickly once treatment ends (e.g., nausea and vomiting, and hair loss). Others become more chronic, arising during active treatment and persisting over time (e.g., fatigue, sexual dysfunction, memory problems, bladder, and bowel problems). While some of these latter symptoms may resolve in the longer term, other sequelae of cancer and its treatment can be permanent (e.g., infertility and amputation). Further, as survivors are living longer, they are surviving long enough to experience effects once considered only as “putative” risks secondary to some treatments (e.g., radiation therapy and certain chemotherapeutic agents). A third category of effects are those that are late-occurring, defined as manifesting 6 months or more after treatment. In addition to recurrence or second cancer,31, 32 risks for other chronic health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis) is also increased.33, 34 Depending on the age of the survivor, these conditions may be of more concern than the cancer itself.35

Table 1 Potential long term and late effects of cancer and its treatment

| Physical/Medical (e.g., second cancers/recurrence, cardiac dysfunction, pain, fatigue, memory problems, sleep disturbance, sexual impairment, infertility, and loss of bowel/bladder control) |

| Psychological (e.g., fear of recurrence, depression, anxiety, lowered self-esteem, and altered body image) |

| Social (e.g., changes in interpersonal relationships, altered family functioning/dynamics, social isolation, altered intimacy, problems advancing at work/returning to school) |

| Financial (e.g., concerns regarding health or life insurance access/coverage, financial strain due to cost of care/job loss) |

| Existential/spiritual issues (e.g., disillusionment, loss of faith, altered sense of purpose or meaning, appreciation of life, benefit finding, and post-traumatic growth) |

Overall, most survivors are remarkably resilient, coping well with what at times can be lengthy as well as physically rigorous treatments. Although a significant subset continues to struggle with emotional distress, by a year or more after treatment, most cancer survivors report levels of emotional well-being equivalent to or better than their peers without a cancer history.36 When it comes to physical health, the picture is different. Compared with those without a cancer history, survivors demonstrate worse physical functioning, higher rates of disability, and more unemployment.37–39 Further, research suggests that lingering physical symptoms commonly occur in clusters (e.g., pain, sleep problems, and fatigue) and greater symptom burden is associated with increased risk of poor quality of life.40

The provision of detail about each of the lingering effects of cancer is beyond the scope of this chapter (for reviews, see Refs ). However, four persistent effects are worth discussing here because they are common across a number of cancers and troubling: fear of recurrence, fatigue, depression, and memory problems. Perhaps the most universal effect of surviving cancer is worry that the disease will return.44 Fear of recurrence can be exacerbated by a variety of triggers (e.g., coming for routine follow-up visits, anniversary dates of diagnosis or treatment, death of a fellow or publicly visible cancer survivor, and any unexplained ache or pain),45 and healthcare professionals see this response as challenging to manage.46 Reassurance that such anxiety is normal and often diminishes over time, along with counsel about what is or, more important, is not a worrisome sign or symptom generally helps to allay concerns. In cases where fear persists and is interfering with daily function and/or recommended follow-up care, referral for brief counseling to see what may be contributing to the anxiety, to learn some relaxation techniques, and to obtain social support can be helpful. Of note, survivors who continue on long-term therapies (e.g., use of adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors) may feel less anxious about the disease coming back. These individuals often report being reassured by the sense that they are doing something active to reduce risk of recurrence.

Fatigue, common during treatment, persists in approximately a quarter to a third of long-term survivors.47, 48 The mechanisms of risk for long-term fatigue are not well understood.49 The importance of addressing this troubling effect of cancer and its therapy is reflected in the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline for assessment of this symptom post-treatment.50 To date, few interventions appear to mitigate cancer-related fatigue, with the exception of exercise. While seemingly counterintuitive, patients who remain physically active during and after treatment report lower, not higher levels of fatigue.51 After ruling out possible physiologic causes of fatigue (e.g., anemia, infection), reassurance that fatigue generally abates over time, albeit far more slowly than once thought, can be helpful in reducing distress about this lingering effect.

Prevalence rates of depression or depressive symptoms among cancer survivors are higher than that observed in the general public, particularly in the early 1–2 years post-treatment.52 Depression is not only painful, but is also associated with delay in return to work and lower adherence to medical regimens in survivors.53 Younger age, being female, and prior history of depression are all associated with increased risk for depression among cancer survivors, yet many survivors experience depression for the first time after a cancer diagnosis.54–56 Survivors and their clinicians need to be aware that cancer treatments can induce depression especially as many people believe that their symptoms are a sign of poor coping or mistakenly assume that depressed mood is expected in the face of cancer.55 Because of the risk for higher all-cause mortality associated with depression, routinely screening for symptoms of depression and referring for treatment is important. Excellent algorithms exist for caring for individuals who are found to be depressed; many can benefit from psychotherapy alone without the need for added medications that many cancer survivors report they are reluctant to take.57, 58

Although long dismissed in the clinical setting, growing attention is now being paid to survivors’ complaints of chronic difficulties post-treatment with memory and concentration. Neurocognitive dysfunction (i.e., difficulty remembering things, thinking clearly and focusing attention, also referred to as “chemo-brain” or “chemo-fog”) is a real and persistent effect of cancer that, more recent studies suggest, may affect between 15% and 25% of survivors in the early re-entry period, with a range as high as 61%.59 The etiology of cancer-related cognitive impairment is multifactorial and may involve systemic proinflammatory cytokines that cross the blood–brain barrier, exposure to chemotherapy, hormonal and biotherapies, and direct treatment toxicities (e.g., surgery, radiation to the brain).60, 61 Both older age and lower cognitive reserve increase risk for cognitive problems after chemotherapy, findings that contribute to the emerging hypothesis that cancer treatments accelerate the aging process.61 A number of promising interventions have been developed to help childhood cancer survivors manage cognitive problems resulting from cancer,62 and more recently, cognitive behavioral therapy interventions are being explored among adult survivors.63

Providing survivorship care

Transitioning to recovery

For many survivors, the relief of completing treatment may be tempered by concerns about what the future holds. The stress associated with transitioning to recovery and life after (instead of with) cancer has multiple sources. First and foremost among these is worry that the cancer will return now that therapy has stopped. General levels of anxiety may increase as patients transition off treatment. Fear in the survivor can have an adverse effect on family quality of life; the reverse also is true, with family members’ fears negatively influencing the quality of life of the survivor.64 When activated, fear may also lead to disruptive behavior such as heightened body monitoring and anxiety well in advance of a doctor visit, and worry about the future. In some instances, severely disabling reactions can occur including hypochondriac-like preoccupation with health at one extreme, or avoidance and denial at the other, along with inability to plan for the future, and despair. Interventions are being developed to help survivors cope successfully with uncertainty.65

Survivors can be taken by surprise by what feels like a paradoxical response to ending treatment, a combination of joy and anxiety. Persistent symptoms (e.g., fatigue, memory problems, and pain syndromes) contribute to a sense of diminished well-being and can lead a survivor to feel she is less well than when treatment was initiated. Loss of the supportive therapy environment (including relationships with staff and fellow patients) must be negotiated. All of this generally occurs in a setting in which family and friends, and even survivors themselves, are ready for everything to be back to “normal.”

Key to navigating this transition is acknowledging that it can be stressful. Having a plan of action for the future is also helpful. In this context, the current demand for the development and delivery of survivorship care plans (SCPs) may provide a ready solution to aid smooth coordination of post-treatment care.

Standards for survivorship care

One of the key recommendations in both the President’s Cancer Panel report on cancer survivorship16 and the IOM report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (whose title aptly describes the survivor’s dilemma when treatment ends14), is that clinicians should provide patients with a comprehensive treatment summary and a tailored plan for follow-up care. Together, these documents comprise what is known as a survivorship care plan or SCP. Although there is not yet consensus on a standard SCP format or content, several common elements are recommended for inclusion. The treatment summary should provide details about the specific cancer (e.g., diagnosis, stage, pathology, and genetic markers if relevant), type of treatments received (e.g., chemotherapy, radiotherapy with dosing and target area as appropriate, hormonal therapy, and biologic agent use), toxicities experienced, treatment response, and risk for late effects, along with the name and contact information for treating physicians. This information is then used to generate a unique plan of post-treatment care. The IOM14 identified 11 elements as part of this document that can be summarized in four broad categories: (1) surveillance for recurrence or new cancers including the nature and timing of these tests; (2) assessment and treatment of or referral to community resources for help with persistent effects of cancer, encompassing psychosocial as well as physical sequelae, acknowledging that psychosocial effects of survival are often overlooked66; (3) recommendations for prevention of future cancer or adverse health conditions, including lifestyle recommendations and potential referral for genetic testing; and (4) specification regarding the components of follow-up care, as well as the contact information for the clinician(s) responsible for delivering follow-up care (Table 2).

Table 2 Essential elements of survivorship care

| Surveillance for recurrence or new cancer (e.g., tests to be performed and their periodicity and changes to be monitored) |

| Assessment and treatment or referral for persistent effects including medical problems (e.g., depression, lymphedema, sexual dysfunction, and functional impairment), symptoms (e.g., pain and fatigue), psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers; and concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability; use of rehabilitation as indicated |

| Prevention of late effects (e.g., second cancers, cardiac problems, and osteoporosis) accompanied by use of genetic testing as indicated; including a focus on health promotion (e.g., diet, weight, physical activity, and sun block use), and management of comorbid conditions |

| Coordination of care (e.g., including frequency of visits, tests and who is performing these) between specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all of the survivor’s health needs are met |

Source: Adapted from Hewitt 2006.14

Despite being strongly recommended in two national reports, use of SCPs has been slow to catch on. In their review of the literature on use of SCPs, Mayer et al.67 arrive at several overarching conclusions: SCPs are broadly endorsed by both patients and providers, but in practice remain underutilized, with large numbers of clinicians reporting failure to deliver these or patients to receive same; while agreement exists among both providers and patients on preferred SCP content, the timing of delivery and who should deliver these is unclear; and finally, limited data exist on the impact of SCP implementation, raising concern about what, if any, difference these documents will make in care delivery or outcomes. These challenges notwithstanding, pressure to embrace SCP use is growing.

In an important step toward making treatment summaries and care plans a part of quality care, ASCO decided to incorporate relevant measures as part of its Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI). A voluntary program opened to ASCO members in 2006, QOPI was created to promote excellence in cancer care by helping oncologists create a culture of self-examination and improvement. In 2008, ASCO added three items to its core set of questions inquiring whether a chemotherapy treatment summary was completed, a copy was provided to the patient, and a copy was also sent or communicated to another practitioner, all within 3 months of chemotherapy end. Somewhat complex templates for cancer surveillance for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer were a regular feature on the ASCO web site. More recently, ASCO released a short SCP template.68 An online tool for building SCPs, Journey Forward, is also readily available, the result of a collaboration of oncology experts, industry, a health insurer, and advocacy groups (http://journeyforward.org/). A number of the key oncology electronic software vendors have begun to develop tools for this purpose as well although lack of interoperability among platforms creates a barrier to their intent, namely, to share information and maximize coordination of care. Key hurdles to optimal SCP use are the personnel time it takes to generate them, lack of easy IT integration to facilitate data capture and exchange, and limited evidence-based guidelines with which to inform recommended care.69 Busy clinicians are hardpressed to use these documents and provide high-quality care because of limited time and budgets. At the same time, SCPs are of limited utility without the intended conversation between patient and provider on their content and use; without these informing dialogues, they are just another piece of paper.

Despite the legitimate concerns about their use, starting in 2015, the American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer is including development and delivery of SCPs as an accreditation criterion.70 Ideally, this action will stimulate thoughtful research regarding who should create and deliver these documents, what is the best approach to doing this, when in the course of care this process should be initiated, and who will pay for this activity. Importantly, understanding whether or not use of SCPs improves patient, provider and system function will be critical.

Models of survivorship care

While it is increasingly recognized that cancer survivors need to be followed for life after treatment, little consensus exists about how this should be done. Anticipated shortages of oncology providers,71 coupled with growing pressure for these professionals to see new patients, makes solving the question of who should provide cancer-related follow-up care a paramount concern.

A number of papers have called for consideration of a shared-care model in which primary care physicians (PCPs) have primary responsibility for follow-up with referral back to oncology or other specialists as needed.72–74 In this model, it is essential that the oncologist provide the PCP with an SCP to communicate key information about the survivor’s illness history, surveillance recommendations, and potential late complications for which to monitor. One large survey suggests that many US PCPs prefer a shared-care model; fewer prefer an oncologist-led model, a PCP-led model, or other specialty survivorship clinics.75, 76 This same study reported PCPs’ confidence regarding their knowledge of survivorship care may be less than optimal.77 However, international studies have found comparable time to recurrence, quality of life, and psychological functioning among survivors followed up by oncology and those followed up in primary care with some element of guidance (e.g., one page of follow-up instructions).78, 79

Other models of follow-up care have also been launched, the most common of these developed at large comprehensive cancer centers, being multidisciplinary, specialized survivorship clinics.80 These tend to offer one of two models: (1) a consultative program in which patients can come at any point post-treatment for review of their history, current function and risk for future problems, and leave with recommendations for care of current problems and an outline of proposed future care to share with their providers; or (2) a full-service program in which survivors can come for regular visits for some specified period of time (e.g., 2–5 years) after cancer treatment. A third model involves nurse-led care in which the nurse serves as a conduit between the care team and the survivor.81–83 Evolution of a given program often reflects the resources of the clinic or facility, the patient population being served, and more generally, the passion of a key leader or leaders to bring the program together and champion funding support for the enterprise. Sustainability for survivorship care programs is a central concern as there is as yet no clear system for reimbursing this care. Models for financing include fee-for-service, insurance reimbursement, research grants, philanthropy, and dedicated program-specific fund raising. Some larger centers see inclusion of a survivorship clinic as “value added” to their operation and will put resources toward support of these programs in the expectation that they will bring more new patients (as well as survivors) to their high-quality facility.

Because of the complexity of cancer and its treatment and the wide variation in what patients bring to their cancer experience (e.g., with respect to pre-existing medical history, function and psychosocial resources), it is clear that one size does not fit all when it comes to models of survivorship care. Additional calls have been made to develop risk-stratified approaches to post-treatment care. In this approach, clinician specialty and visit frequency depend on survivor needs and risk for recurrence and late effects.84, 85 Low-risk survivors (e.g., early-stage breast or colorectal cancer receiving surgery only) may be transferred right back to primary care shortly after conclusion of treatment. High-risk survivors (e.g., those undergoing stem-cell transplant or with more complex care needs) would be seen regularly by oncology with routine care addressed by the PCP.72, 73 A risk-stratified model of care is currently being tested in Great Britain (http://www.ncsi.org.uk/what-we-are-doing/risk-stratified-pathways-of-care/risk-stratification/). For this type of care to become more common, evidence-based predictive models are needed for survivors most likely to experience negative sequelae after cancer.

Regardless of the model used, two central tenets of survivorship care remain constant: coordination of care is critical if survivors are to receive optimal post-treatment follow-up, and survivors themselves necessarily play an important role in their healthcare and outcomes. While current survivorship care in the United States involves multiple providers from a variety of specialties,86 no system for communication and coordination among these individuals or teams has been established.87 Furthermore, until such time as there is consensus about which providers are responsible for, or appropriately skilled in, the essential components of survivorship care,77, 88, 89 survivors are at risk of care that is potentially duplicative, inappropriate (e.g., over testing in the absence of proven utility of special scans or tumor markers), or ineffective in reducing cancer-related morbidity. Even some oncologists report incomplete knowledge of the late effects of cancer treatment.90 To maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of survivorship care, clear communication is crucial at the end of cancer treatment between patients and their providers, as well as cancer providers and their patients’ PCP and other specialists, about who is going to provide what kind of care, and when and where this will be delivered. Increased efforts are needed in training diverse healthcare providers about the long-term and late effects of cancer and developing guidelines for delivery of optimal survivorship care. Toward this latter goal, guidelines released by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),91, 92 ASCO,68, 93 and the American Cancer Society (ACS)94 are already available for advancing survivorship care. Similar efforts are occurring globally.95

For their part, survivors may expect that if they continue to see their oncologist years after treatment, he or she is providing primary care.96 In addition to serving as a communication vehicle between clinicians, SCPs can facilitate survivors’ education about their role in managing post-treatment health. Self-management interventions have been shown to improve survivors’ quality of life, psychological functioning, and health behaviors. The care received is also more likely to be consonant with survivors’ needs and goals when survivors actively participate in treatment-related decision making.97

Rehabilitation and health promotion

As the goal of cancer therapy expands beyond merely curing or controlling disease to optimizing function and quality of life after cancer, two additional aspects of care have emerged as central to these aims: rehabilitation and health promotion. Use of cancer-related rehabilitation in the United States has diminished over time, in part reflecting earlier diagnosis (hence less need for more aggressive treatments) and broader use of more limb- and tissue-sparing approaches to surgery. Concern about the persistent effects of cancer and its treatment, however, are causing clinicians to rethink use of these services, access to which remain a standard of care in many countries outside the United States.98, 99 Survivors report multiple rehabilitative needs after cancer,100 and research suggests that attending to these, both preventively and after the fact,101 can reduce cancer-related morbidity and mortality. A licensed program designed to meet the rehabilitative needs of cancer survivors has been adopted by several sites across the United States.102 In 2013, the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitative Facilities (CARF) developed certification standards for cancer rehabilitation.103 How quickly incorporation of these types of services occurs in large cancer centers remains to be seen.

Interest in health promotion after cancer has grown in the past decade driven by multiple factors, including demand by survivors themselves. Most cancer survivors are older, often present with comorbid conditions that are exacerbated by cancer treatment or are at increased risk for comorbid health problems (e.g., cardiac problems, obesity, and osteoporosis) as a function of treatment, develop poor health habits while in active treatment (sedentary and poor diet), are aging, and could benefit from lifestyle interventions. Importantly, survivors often ask their care team what they can do to reduce the risk of a recurrence and regain health after cancer. Because of these factors, researchers see cancer as a “teachable moment.”104

The benefits of healthy lifestyle are well known in association with prevention of cancer, covered elsewhere in this volume. Among cancer survivors, observational studies suggest that smoking cessation, increased physical activity, and weight control may reduce the risk of cancer recurrence, cancer specific mortality, and overall mortality,105–107 although randomized clinical trials are still needed to support causal statements about the effects of behavior change. The consistency of the data behind the benefits of remaining or becoming more physically active during and after cancer is sufficient for clinicians to recommend their patients strive to be up and about right from the start of treatment. The ACS provides and regularly updates guidelines for cancer survivors about nutrition and physical activity after cancer.108 While some survivors change their behavior spontaneously,109 many do not.110 Survivorship care provides an important opportunity for clinicians to support cancer survivors’ efforts to make changes in dietary behaviors, levels of physical activity, smoking, and stress management that have the potential to reduce risk of recurrence, second malignancies, and comorbid health conditions, an opportunity currently being missed by many practitioners.111, 112 More research is urgently needed on how providers can effectively deliver health promotion assistance and how survivors can successfully implement and sustain beneficial changes.

Families and informal caregivers

Because the advocacy community considers informal caregivers to be cosurvivors, no discussion of survivorship care is complete without consideration of the family caregiver. With the majority of cancer care now delivered in the outpatient setting and many more individuals living long-term after cancer, large numbers of whom will live with cancer as a chronic illness, the burden of cancer on families is rising rapidly. Research suggests that family caregivers frequently feel ill-prepared for the demands of care for their loved one, receive little or no guidance on what to do, and often strain under the demands of competing roles, including holding jobs, managing children, and caring for their own health.113 One study found that two out of five caregivers experience moderate psychological distress and one out of five desires formal support.114 Caregivers may worry more about recurrence than the survivor.64 Unrealistic expectations for a speedy return to life as usual can contribute to anxiety that lingering symptoms may reflect return of the disease and resentment that recovery is taking too long and lead to disruptions in family functioning.

Providing both cancer survivors and their caregivers with information about what to expect in the first 6 months after treatment ends is vital to reduce distress in both parties. Dyadic studies indicate that health outcomes in both patients and their caregiver partners are mutually dependent.115–117 Because family caregivers, like their care recipients, tend to be older adults and at risk of their own comorbid health conditions (including cancer), it is possible that healthy lifestyle education efforts with the survivor may also benefit the caregiver, although this effect remains to be tested. Moreover, involvement of family caregivers can be critical to ensuring survivors’ adherence to recommended adjuvant therapies, follow-up visits, and symptom control and reporting. Thus, ensuring that this vital support system is functioning well can provide an enormous asset to providers in effectively managing their patients’ care. Already a number of cancer centers are striving to include services for caregivers as part of their comprehensive care.118

Conclusion

The growing population of cancer survivors has taught us several lessons. First, that cancer survivorship—defined as the period that extends from completion of curative therapy until recurrence or death from cancer or another event—represents a distinct phase along the cancer control continuum. It brings its own unique set of challenges and opportunities for recovery and growth. Second, the majority of survivors will live years beyond their initial diagnosis. Those treated as children, adolescents, or young adults have the potential to live a lifetime with a cancer history. However, few of our current therapies are entirely benign; most have some degree of associated toxicity and a number produce considerable adverse physical as well as psychosocial sequelae. Consequently, third, all of these chronic and late effects must be tracked and actively addressed. Fourth, while a subset of survivors continues to struggle after cancer treatment ends, most are remarkably resilient. Nevertheless, the capacity of survivors and their healthcare providers to realize the shared goal of good quality of life and function requires collaboration and communication between both groups. Defining and delivering high-quality survivorship care, albeit a high-end problem, constitutes a significant challenge for cancer medicine. Success, in our efforts to reduce undue suffering and premature death due to cancer, will require continued investment in survivorship research. It will also require enhanced commitment to the training and support of current and future generations of multidisciplinary providers who care long term for those treated for cancer. While a number of questions remain about how to achieve these lofty goals, the resources to do so are evolving rapidly. Further, a number of evidence-based programs have evolved to address survivors’ post-treatment needs. Though far from perfect, these are good enough to begin disseminating.119 Increased attention will be needed, nevertheless, to promote tailoring of care to older adult cancer survivors, a surprisingly neglected population.120 Along with interest in the field of cancer survivorship more generally, the number of survivorship scientists and practitioners is expanding steadily both in the United States and abroad.121, 122 There is broadening public awareness of the importance of managing the care of those with chronic illnesses like cancer, and the advocacy community championing cancer survivorship needs remains strong. The next decade will permit us to promote and measure the impact of collective efforts to enable more survivors and their families to thrive after cancer.

Summary

- The number of individuals in the United States with a cancer history will continue to grow over the next two decades, driven largely by the aging of the population. By 2022, there will be 18 million cancer survivors, approximately two-thirds of whom will be age 65 or older.

- Cancer survivorship—defined as the period that extends from completion of curative therapy until recurrence or death from cancer or another event—represents a unique place on the cancer control continuum and is accompanied by its own set of health care challenges.

- Cancer and its treatment can cause a variety of persistent (e.g., pain, fatigue, memory problems, and sexual dysfunction) as well as late-occurring (e.g., second cancers, cardiac problems, diabetes, osteoporosis, and depression) adverse sequelae. Often occurring in clusters, these effects can have a negative impact on every aspect of a survivor’s life: physical, psychological, social, economic, and existential.

- Most cancer survivors are remarkably resilient and adapt well after cancer. However, a significant subset struggle with the aftermath of their illness. Use of systematic assessment at the end of treatment with early identification and referral of those in need of additional support is important.

- Use of SCPs to improve quality of and communication around post-treatment care is growing. In addition to a treatment summary, essential elements of an SCP include plans for (1) surveillance for recurrent or new cancers; (2) assessment and treatment of persistent effects of cancer; (3) prevention of late consequences, including use of genetic testing and health promotion; and (4) coordination of care.

- No consensus exists on the best model for follow-up care delivery. Currently, multiple models are being examined. Interest is growing in the development of models that (1) involve shared care between oncology and primary care providers and (2) are structured around risk-based algorithms (e.g., survivors with early-stage disease and minimal treatment would return quickly to their PCP, whereas those at high risk of recurrence would remain more closely connected with oncology care teams and centers).

- Survivorship may provide a “teachable moment” for clinicians to help cancer survivors pursue healthy lifestyles and behaviors.

- Attention must be given to the psychological and physical well-being of family caregivers in the recovery process. Viewed as “secondary survivors,” informal caregivers play an important role in survivors’ recovery and yet may struggle themselves with this transition to a “new normal.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree