Cancer of the Penis and Male Urethra

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

The basic structural components of the penis include two corpora cavernosa and the corpus spongiosum. These are encased in a dense fascia (Buck’s fascia), which is separated from the skin by a layer of loose connective tissue. Distally, the corpus spongiosum expands into the glans penis, which is covered by a skin fold known as the prepuce. The skin extends over and is firmly attached to the glans.

The male urethra is composed of a mucous membrane and the submucosa. It extends from the bladder neck to the external urethral meatus. The posterior urethra is subdivided into the membranous urethra, the portion passing through the urogenital diaphragm, and the prostatic urethra, which passes through the prostate. The anterior urethra passes through the corpus spongiosum and is subdivided into fossa navicularis (a widening within the glans), the penile urethra, which passes through the pendulous part of the penis, and the bulbous urethra, the dilated proximal portion of the anterior urethra. The prostatic urethra is covered by transitional epithelium only. The distal portion of the anterior urethra is covered by stratified squamous epithelium, which changes proximally to pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The columnar epithelium gradually changes into transitional epithelium in the membranous urethra.

The lymphatic channels of the prepuce and the skin of the shaft drain into the superficial inguinal nodes located above the fascia lata. The rich anastomotic network of the lymphatics within the penis and at the base of the penis means that for practical purposes lymphatic drainage may be considered bilateral. There is some disagreement as to whether the glans and the deep penile structures drain into the superficial or deep inguinal lymph nodes (those under the fascia lata). The so-called sentinel nodes located above and medial to the junction of the epigastric and saphenous veins have been identified as the primary drainage sites in carcinoma of the penis.1 Selective biopsy of this group of nodes is of obvious importance in assessment of tumor extent, because, if they are not involved by tumor, a complete nodal dissection may not be necessary. The reliability of this procedure has not been supported by some.2,3 Catalona4 found that biopsy of the sentinel nodes showed false-negative results in 10% of Cabanas’s5 cases who died of carcinoma.

The lymphatics of the fossa navicularis and the penile urethra follow the lymphatics of the penis to the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes. The lymphatics of the bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra may follow three routes. Some pass under the pubic symphysis to the external iliac nodes, some go to the obturator and internal iliac nodes, and others end in the presacral lymph nodes. The pelvic (iliac) lymph nodes are rarely involved in the absence of inguinal lymph node involvement.6

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Carcinoma of the penis is rare in the United States, where an estimated 1,100 new cases will be diagnosed each year.7 The annual incidence is estimated to be 1 in 100,000 males, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers in men.6 There is increasing evidence that newborn circumcision has a preventive effect in the development of carcinoma of the penis.8 This tumor is extremely rare in circumcised Jewish men;6 circumcision performed early in life protects against carcinoma of the penis, but this is not true if the operation is done in adult life.9 The higher incidence in some areas of South America, Africa, and Asia seems to be related to the absence of the practice of neonatal circumcision. It has been shown that male circumcision is highly effective in preventing the development of penile carcinoma in Nigeria and Uganda.10,11 The high incidence of carcinoma of the penis in American blacks has similarly been attributed to the lower percentage of blacks undergoing neonatal circumcision. Phimosis is common in men suffering from penile carcinoma. Smegma is carcinogenic in animals, yet the component of the smegma responsible for its carcinogenic effect has not been identified.6

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is associated with penile carcinoma. In a systematic review of the literature, Miralles-Guri et al.12 concluded that approximately half of all carcinomas are HPV related, with the most common serotypes being HPV-16 and HPV-18. Boon et al.13 observed an increased incidence of cervical carcinoma and penile carcinoma in Bali in a Hindu population in whom circumcision is rare and phimosis in adult males is high. They suggested that HPV infection, estimated to be present in over 75% of Balinese patients with genital carcinoma, may be a cofactor with impeded postcoital hygiene in genital carcinogenesis. In the Netherlands, where males are usually circumcised, the male is exclusively a vector of HPV but not a victim as in Bali. Martinez14 in Puerto Rico and Graham et al.15 in New York also noted a significantly higher incidence of carcinoma of the cervix in the wives of males with penile carcinoma.

The quadrivalent vaccine against HPV serotypes 6, 11, 16, and 18 has been approved for females aged 9 to 26 to prevent cervical cancer. Based on the demonstrated ability to significantly decrease the incidence of penile lesions (primarily HPV-6 and HPV-11 associated genital warts) in young men, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration also approved the use of the vaccine in males aged 9 to 26. Because the incidence of penile cancer in the United States is much lower than that of genital warts, the reduction in penile cancer incidence is expected to be low. However, there is potential great benefit to vaccination in countries with much higher penile cancer rates. Perhaps the greatest benefit of vaccination of young men in the United States would be the reduced HPV infection rate in the overall population and subsequent reduced transmission to females at risk for cervical cancer.16 Other etiologic factors, such as other viruses (herpes simplex) and venereal disease (syphilis), have been implicated,17,18 but the evidence remains inconclusive.5

Carcinoma of the male urethra is also rare. There are no recognized racial or geographic predisposing factors. Although the etiology remains unknown, there seems to be some correlation between the incidence of carcinoma of the urethra and chronic irritation (infection, venereal diseases, strictures). Significant past medical history of male urethra cancer patients include venereal disease (24% to 37%), urethral stricture (35% to 54%), urethral trauma (7%), and urethral polyps (2%).19,20 The part of the urethra covered by the transitional epithelium (prostatic and membranous urethra) may be susceptible to the same carcinogenic factors that affect the bladder and the upper urinary tract. Average age at presentation of these tumors is 58 to 60 years, although 10% occur in men younger than 40 years.5,20

NATURAL HISTORY

NATURAL HISTORY

Most carcinomas of the penis start within the preputial area, arising in the glans, coronal sulcus, or the prepuce itself. Lesions arising in the skin of the shaft are rare. In most patients, carcinoma of the penis is characterized by slow locoregional progression. The penis is handled and observed daily, yet there is often significant debate as to when patient recognition and medical diagnosis should have occurred. The patient experiences fear and embarrassment, which probably contributes to delayed diagnosis. Therefore, expeditious diagnosis of all penile lesions should be the rule. Extensive primary lesions may involve the corpora cavernosa or even the abdominal wall. The inguinal lymph nodes are the most common site of metastatic spread. Pathologic evidence of nodal metastases is reported in about 35% of all patients and in approximately 50% of those with palpable lymph nodes.5,17,21,22

Distant metastases are uncommon (about 10%), even in patients with advanced locoregional disease, and usually occur in patients with inguinal lymph node involvement. These patients often die of septic complications, erosion of large vessels in the groin, or a combination of the two.

The natural history of carcinoma of the anterior urethra in the male is similar to that of carcinoma of the penis. Approximately 40% of tumors originate in the anterior urethra.19 Many tumors are low grade and progress slowly at primary and regional sites rather than spread to distal areas. Tumors of the penile urethra spread to the inguinal lymph nodes first, whereas those of the bulbomembranous and prostatic urethra metastasize first to the pelvic lymph nodes. Approximately one-third of men will present with either clinically or pathologically involved lymph nodes.19

Urethral cancers tend to spread by direct extension to adjacent structures. Invasion into the vascular space of the corpus spongiosum in the periurethral tissues is common. Malignancies beginning in the bulbomembranous urethra often invade the deep structures of the perineum, including the urogenital diaphragm, prostate, and adjacent skin. In the majority of prostatic urethral tumors, the bulk of the prostate gland is invaded at the time of diagnosis. Hematogenous spread is uncommon except in advanced regional disease. Kaplan et al.20 reported distant metastases in about 15% of patients; most had corpora cavernosa invasion at diagnosis.

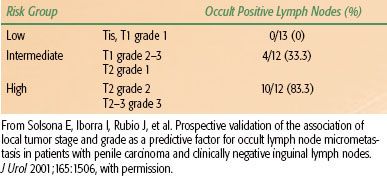

FIGURE 68.1. Localization of the primary tumor in 259 patients; each circle represents one anatomic compartment. Intersections indicate involvement of two or three compartments. Unknown: two. (From Rozan R, Albuisson E, Giraud B, et al. Interstitial brachytherapy for penile carcinoma: a multicentric survey (259 patients). Radiother Oncol 1995;36:83–93, copyright 1995, with permission from Elsevier.)

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Carcinoma of the penis may present as either an infiltrative-ulcerative or an exophytic papillary lesion. Figure 68.1 demonstrates the localization of penile tumors in 259 patients from 14 cancer institutes in France. The glans and the prepuce were the predominant sites of the primary lesion, whereas tumors of the shaft were rare.23 Assessment of the primary lesion may be obscured by the presence of phimosis. Secondary infection and associated foul smell are quite common. Urethral obstruction is an unusual symptom of carcinoma of the penis. The most common presenting symptom is a mass, which occurs in over two-thirds of patients. Ulceration is also common, occurring in approximately half of patients.22,24 In a collective series of 552 patients with penile carcinoma, the presenting symptoms were mass lesions (78%), pain or itching (12%), bleeding (7%), groin mass (7%), and urinary symptoms (4%).25–27 Inguinal lymph nodes are palpable on presentation in 30% to 45% of patients;5,17,21,26,28,29 however, only half contain tumor.21,22 Enlargement of the lymph nodes is often related to inflammatory (infectious) processes. Administration of antibiotics over several weeks results in regression of inguinal lymph nodes in a substantial proportion of cases and many have advocated this practice before the status of the regional lymph nodes is definitively assessed. Conversely, between 20% and 40% of patients with clinically negative inguinal lymph nodes have occult metastases.3,30–33

Patients with urethral carcinoma most commonly present with obstructive symptoms (43%). Other presenting signs and symptoms include mass (28%), bleeding (20%), abscess (20%), and irritative symptoms (20%).19 These symptoms are often attributed to urethritis or urethral stricture, which may precede the development of urethral carcinoma and may also result in delay in diagnosis. The majority of urethral carcinomas occur in the bulbomembranous (posterior) region (61%), and tumors in this location have a worse prognosis compared with those arising in the anterior urethra.19

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

Diagnostic studies are required in the evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed carcinoma of the penis and urethra. Urethroscopy and cystoscopy are essential for urethral primaries. Inguinal lymph nodes should be thoroughly evaluated. Computed tomography (CT) is useful in the identification of enlarged pelvic and periaortic lymph nodes in patients with involved inguinal lymph nodes.

Limited prospective data regarding the use of positron emission tomography (PET) with CT are available, but preliminary results show encouraging sensitivity (88%) and specificity (98%) in evaluating inguinal lymph nodes34 and a diagnostic accuracy of 96% in evaluating pelvic lymph nodes in patients with known inguinal metastases.35

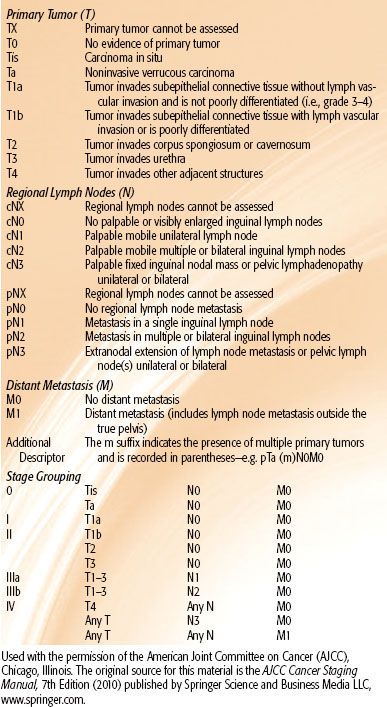

TABLE 68.1 AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE STAGING SYSTEM FOR CARCINOMA OF THE PENIS

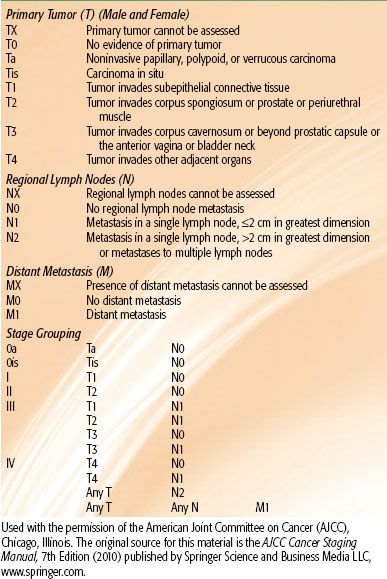

TABLE 68.2 AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE STAGING SYSTEM OF CARCINOMA OF THE URETHRA

STAGING

STAGING

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging systems for carcinoma of the penis and urethra are shown in Tables 68.1 and 68.2, respectively.36

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

Most malignant penile tumors are well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas.37 Although an apparent adverse prognostic effect of anaplasia has been reported in some series,17 others found no significant correlation between histologic grade and survival.18,26

Bowen disease is squamous cell carcinoma in situ that may involve the shaft of the penis as well as the hairy skin of the inguinal and suprapubic area. Clinically, the lesion is a solitary, dull-red plaque with areas of crusting and oozing. Approximately 25% to 50% of patients with this disease have a concomitant visceral malignancy.6

Erythroplasia of Queyrat is an epidermoid carcinoma in situ that involves the mucosal or mucocutaneous areas of the prepuce or glans.37 It appears as a reddened, elevated, or ulcerated lesion. Graham and Helwig38 reported that 10 of 100 patients presenting with erythroplasia of Queyrat had invasive squamous cell carcinoma at diagnosis. Mikhail39 reported on 5 of 15 patients with the same presentation. Erythroplasia of Queyrat is not as frequently associated with internal malignancies as Bowen’s disease.40

Basal cell carcinoma is infrequently reported, accounting for 1% to 2% of all cases of penile cancers.41,42

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial apocrine carcinoma. The most common sites are the scrotum, inguinal folds, and perineal region.39 The lesion has a propensity to metastasize, necessitating frequent assessment of regional nodes. Radiation therapy has been recommended as palliative treatment.39

Soft tissue tumors are uncommon. Approximately half of the tumors are benign and may include angiomatous, neurogenous, myogenous, fibrous, and lymphoreticular tumors.43,44 Most soft tissue tumors occur on the shaft and are malignant.

Primary lymphoma of the penis was reported in one patient with Peyronie disease, without other evidence of lymphomatous involvement. Five cases of secondary involvement of the penis by lymphoma were reported in the literature.45

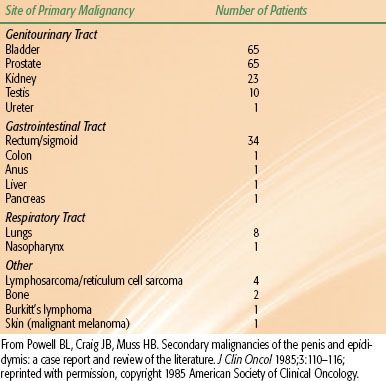

Cancers metastatic to the penis are rare and usually represent late, advanced carcinomatosis. The most common neoplasms metastasizing to the penis are from the genitourinary organs, followed by the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems (Table 68.3). The predominant cell type is carcinoma, occurring in 202 of 219 cases.46 Sarcomas and tumors of unknown histologic type are rare. A palpable mass, swelling, nodule, or skin change frequently occurs. Priapism as an initial presenting feature or subsequent development occurs in 40% of patients.46

The histological subtypes in the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center series of urethral cancers included squamous cell carcinoma (52%), transitional cell carcinoma (33%), epidermoid carcinoma (11%), adenocarcinoma (2%), and anaplastic carcinoma (2%).19 Primary malignant melanoma arising from the urethra has been reported.47,48 The frequency of histologic type varies with site. Over 90% of carcinomas of the prostatic urethra are of transitional cell type. Adenocarcinomas occur only in the bulbomembranous urethra.

TABLE 68.3 PRIMARY MALIGNANCIES ASSOCIATED WITH SECONDARY CANCERS OF THE PENIS IN 219 PATIENTS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

The principal prognostic factors in carcinoma of the penis are extent of the primary lesion and status of the lymph nodes.24,49 The incidence of nodal involvement is related to the size, location, and grade of the primary lesion. Invasion of deep-seated structures (corpora cavernosa) carries a high risk of deep inguinal node involvement.

Tumor-free regional nodes imply an excellent (80% to 90%) long-term survival or cure.21,29,49 Patients with involvement of the inguinal nodes fare considerably worse, and only 40% to 50% survive long term.21,29,49,50 Pelvic lymph node involvement implies a still worse prognosis; less than 20% of these patients survive.5,21,26 Gerbaulet and Lambin51 reported the results of 109 patients with carcinoma of penis at Institut Gustave-Roussy. The actuarial survival rates of patients with negative nodes were 82% at 5 years and 59% at 10 years. For patients with positive nodes, the survival rates were 36% and 18%, respectively. The number of positive lymph nodes has also been reported to have prognostic significance. Brkovic et al.52 reported a 5-year survival rate of 71% in patients with solitary inguinal lymph node metastasis compared with 33% in patients with multiple positive inguinal nodes.

Tumor differentiation was shown to be an important prognostic factor by Fraley et al.53 None of 9 patients with carcinoma in situ, 1 of 20 with well differentiated, 5 of 13 with moderately differentiated, and 3 of 4 with poorly differentiated lesions died of their tumors. Other investigators have confirmed the prognostic significance of tumor grade.24,49,54,55

Carcinoma of the penis has been reported to have greater propensity to metastasize and poorer prognosis in patients younger than 50 years of age53 and patients older than 65 years of age.54 Soria et al.24 reported younger age at presentation adversely affected disease free survival, but not overall survival. Conversely, Marcial et al.56 observed no difference in survival in relation to age.

The potential influence of HPV on prognosis was studied retrospectively in a cohort of patients treated surgically. HPV DNA was detected in paraffin-embedded specimens in 30% of patients. The presence of HPV had no prognostic significance with regard to lymph node metastasis or overall survival.57

Overall prognosis in males with carcinoma of the urethra varies considerably with location of the primary lesion.19,58–63 Distal lesions generally have a prognosis similar to that of carcinoma of the penis. Lesions of the bulbomembranous urethra are usually quite extensive and are associated with a dismal prognosis. Dalbagni et al.19 reported a 5-year overall survival of 69% in patients with anterior tumors compared with 26% in patients with posterior tumors. Other prognostic factors included lymph node status and histology (superficial vs. invasive). Tumors of the prostatic urethra show prognostic features similar to those in bladder carcinoma. Superficial lesions have a good prognosis and may be managed with transurethral resection.61 Deeply invasive tumors have a greater tendency to develop inguinal or pelvic lymph node and distant metastases.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

Carcinoma of the Penis

Conservative Therapies

Treatment for carcinoma in situ and very small penile carcinomas includes topical imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).64 For larger lesions, conservative laser surgery65 or Mohs micrographic surgery is used.66

Surgery

Treatment of patients with carcinoma of the penis is generally performed in two phases: initial management of the primary tumor and later treatment of the regional lymphatics. Surgical intervention at the primary site may range from local excision, including circumcision, or laser surgery67 in a small group of highly selected patients, especially those with small lesions of the prepuce, to partial or total penectomy.22,52,54 In very advanced proximal tumors, more aggressive resections such as total emasculation (penectomy, scrotectomy, orchiectomy) or cystoprostatectomy may be indicated.68 Although surgical resection is a highly effective and an expedient treatment modality in most cases, it may not be acceptable to sexually active patients. Radical surgery, especially total penectomy, may be psychologically devastating to the patient. The ideal surgical procedure removes the disease with adequate margins while preserving sexual and urinary function, although this is not always possible because of the extent of disease. The high local recurrence rates described in some reports with limited surgery69,70 illustrate the need for careful patient selection in choosing a surgical approach. Lesions confined to the prepuce may be treated with wide circumcision. Microsurgical techniques have shown local excision to be an acceptable and desirable option with small superficial lesions. A local control rate of 92% was achieved in 29 patients with a 5-year survival rate of 81% for stage I and 57% for stage II lesions.71 Lesions on the glans penis have traditionally been treated by partial penectomy. Larger or more invasive lesions (stage III) can be treated by partial or total penectomy. Partial penectomy is the procedure of choice if surgical margins of 2 cm can be achieved. If an adequate margin cannot be achieved, total penectomy with perineal urethrotomy is warranted. Local (stump) recurrence is quite rare.5 It is possible for some patients to remain sexually active after partial penectomy. Jensen72 reported 45% of patients with 4 to 6 cm and 25% of patients with 2 to 4 cm of penile stump could perform sexual intercourse. D’Ancona et al.73 evaluated the quality of life in 14 patients treated with partial penectomy. Sexual function was reported to be normal or only slightly decreased in 64% of patients. Complete loss of sexual function was reported in 14% of patients.

Surgical Treatment of Inguinal Lymph Nodes

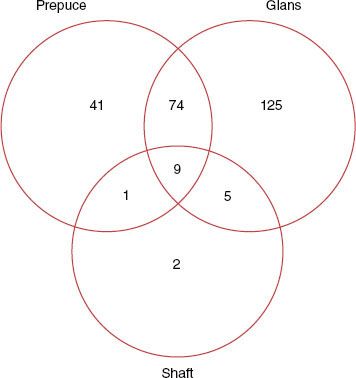

The clinical evaluation of inguinal lymph nodes in men with cancer of the penis is unreliable. Several series have shown the sensitivity of clinical staging of the nodes to be 40% to 60% and false-negative rates to be 10% to 20%.3,4 McDougal et al.74 reported the correlation between clinical findings and pathologic positivity of inguinal nodes in patients with penile carcinoma. For tumors with no invasion or superficial invasion, moderately or well differentiated, only 12% of clinically enlarged inguinal nodes were pathologically positive. However, 78% to 88% of invasive or poorly differentiated tumors metastasized to inguinal nodes regardless of clinical findings. In a prospective study involving 37 patients with clinically negative groins, Solsona et al.33 have demonstrated the predictive value of histologic grade and T stage in predicting the likelihood of occult positive lymph nodes. Three groups were identified: low, intermediate, and high risk with an incidence of occult positive nodes of 0%, 33%, and 83%, respectively (Table 68.4). Given the unreliability of clinical assessment, a rationale exists to submit all patients to the staging and therapeutic benefits of radical inguinal lymph node dissection. However, this procedure is associated with considerable morbidity. Up to one-half of patients will experience complications including wound necrosis or dehiscence, infection, lymphocele, erosion of femoral vessels, chronic lymphedema, thrombophlebitis, or pulmonary embolism.50,68 The morbidity of radical lymphadenectomy and the relative small percentage of patients with pathologic involvement of inguinal nodes have resulted in surveillance as the initial management of regional lymph nodes in clinically negative patients at some centers.

Of concern, however, are reports describing poor salvage rates after regional failure. McDougal et al.74 reported a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 88% for patients with clinical stage II disease who underwent immediate lymphadenectomy compared with 38% if delayed lymphadenectomy was performed. Johnson and Lo75 reported that only one of eight patients undergoing late inguinal node dissection survived 5 years. Fraley et al.53 noted an 88% 5-year survival rate with immediate lymphadenectomy compared with 8% with a delayed procedure. Sentinel node biopsy has been advocated as a less morbid means of evaluating inguinal nodes by some,4 but its reliability has been questioned by others.2,76 Catalona4 and Colberg et al.77 described a modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for patients with penile cancer and clinically negative groins. Long-term follow-up of nine patients reveals significantly less morbidity than the classic groin dissection designed by Daseler et al.78 Extension of the nodal dissection into the pelvis to cover the iliac lymph nodes is justified in patients with evidence of inguinal involvement (positive biopsy of Cloquet’s node). Approximately 20% of patients with pelvic lymph node involvement can be salvaged by radical pelvic lymphadenectomy.5,79

As demonstrated in other anatomic sites, such as the head and neck, uterine cervix, vagina, and vulva, patients with clinically negative lymph nodes who are at risk for microscopic nodal metastases (primary tumor beyond stage I or less than well-differentiated histology) can receive elective irradiation to the inguinal lymph nodes with a high probability of tumor control and low morbidity.

TABLE 68.4 T STAGE AND GRADE PREDICT THE RISK OF OCCULT POSITIVE LYMPH NODES