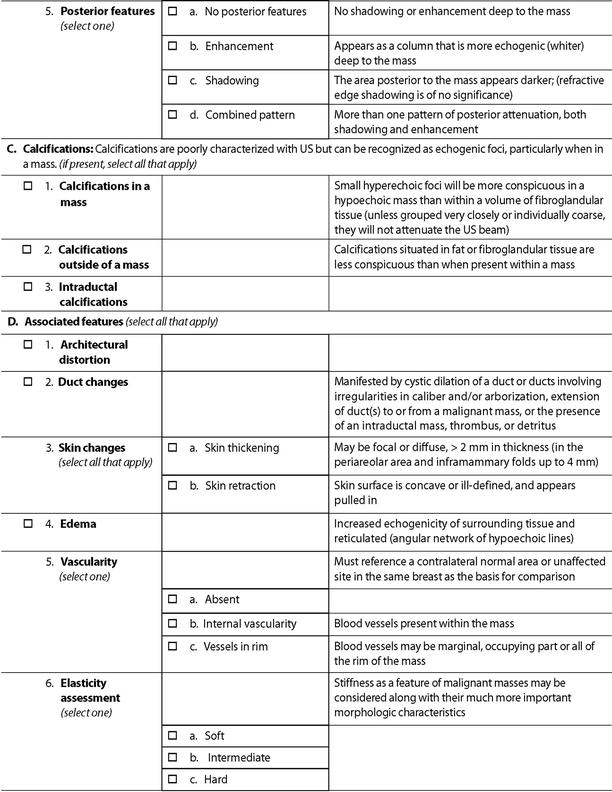

There are a total of six descriptors in the BI-RADS-US lexicon for a mass that is visible in two projections (Table 7.1). The shape of a mass is described as being oval, round, or when neither as irregular. The orientation of the lesion is noted as being parallel to the skin surface indicating a horizontal orientation or as being not parallel, meaning in a vertical orientation or being round. The margin of the lesion is described as being circumscribed or not. When not circumscribed, the appearance is noted as being indistinct where no clear demarcation exists (Fig. 7.1), angular when sharp corners or borders forming acute angles is observed, microlobulated when the margin has a scalloped appearance, or spiculated when sharp lines project from the mass. Mass margins are especially important descriptors, and the distinction between circumscribed and noncircumscribed margin is critical since this distinction determines whether biopsy is required or if a mass can be followed up.

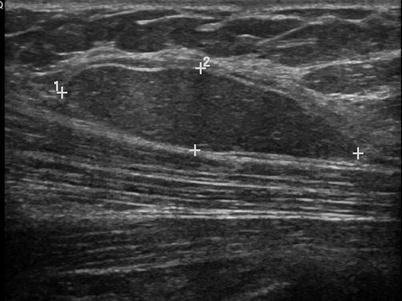

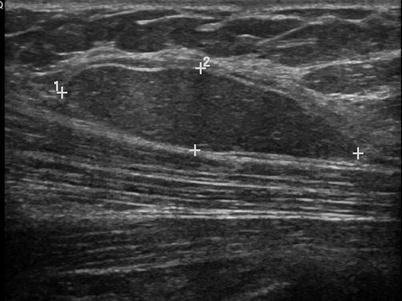

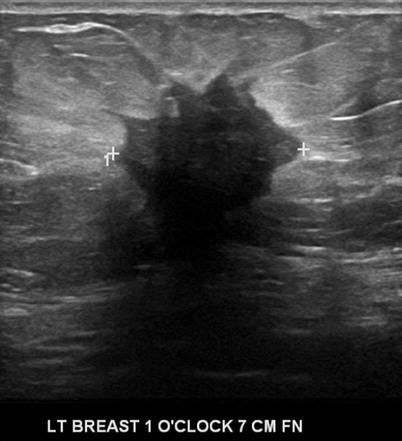

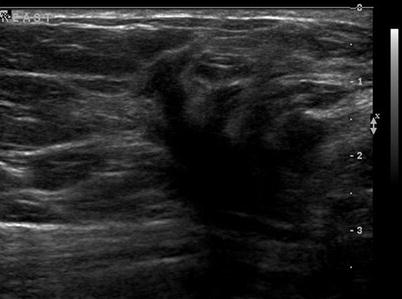

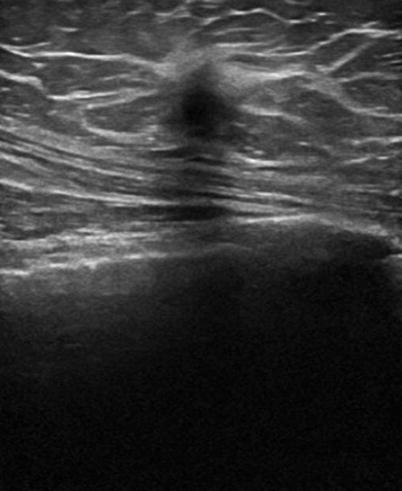

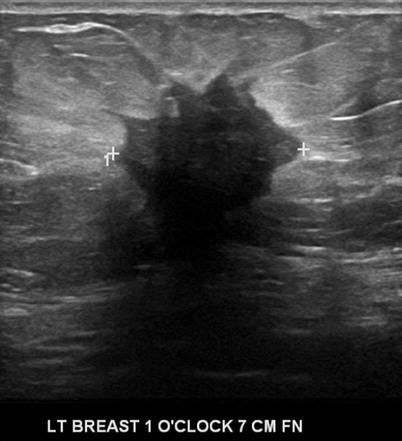

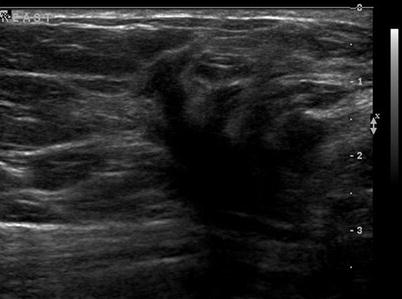

Fig. 7.1

A solid mass whose margins are indistinct. Histological diagnosis: invasive lobular cancer

The echo pattern of the mass is either anechoic when no internal echoes are visible, hyperechoic when internal echoes are greater than that of fat or equal to fibroglandular tissue, complex when a combination of anechoic and echogenic components are seen, hypoechoic relative to fat indicating presence of low-level echoes, or isoechoic meaning having an echogenicity similar to fat. Fibroadenomas and complicated cysts typically are hypoechoic or isoechoic. Posterior acoustic features are described as being absent, enhanced, shadowing, or a combination of the latter two. Lesion boundary and surrounding tissue are also suggested although not commonly used.

Appropriate Indications for the Use of Breast Ultrasound [1–15]

Breast ultrasound is an established modality in the evaluation of the breast and is broadly used for two major indications, one as a supplemental method to assess abnormalities that are identified on a screening mammogram or in the evaluation of a breast symptom, most important of which is a patient with a palpable abnormality of the breast. There are guidelines suggested for the use of breast ultrasound by the American College of Radiology and the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine [1, 2]. Use of ultrasound as a screening modality is somewhat controversial and is discussed elsewhere in this textbook. The American College of Radiology appropriateness criteria provide guidance for appropriate triaging of women depending on the age of the patient and specific indication (Tables 7.2 and 7.3) [14, 15]. Detailed descriptions of the appropriateness criteria can be found in Appendix 7A and Appendix 7B at the end of this chapter.

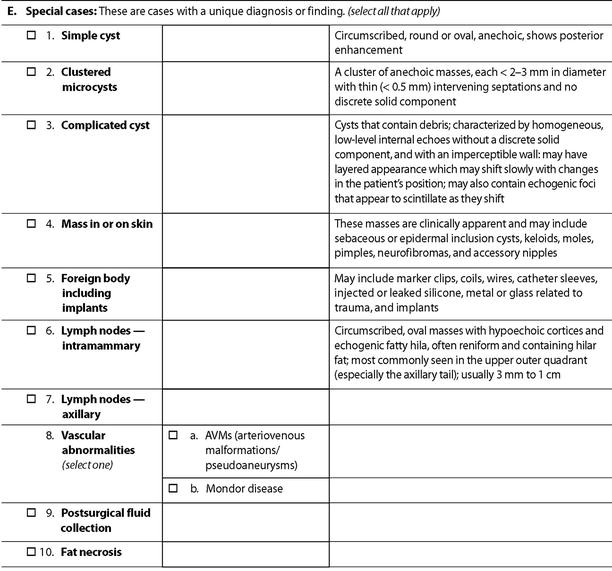

Table 7.2

Appropriateness of use of ultrasound following a nonpalpable finding on a screening mammogram

Indication | Procedure rating for next exam to perform |

|---|---|

Architectural distortion: no history of surgery or trauma | 1 |

Architectural distortion: history of surgery or trauma at area of distortion | 1 |

Mass seen on a mammogram indistinct, microlobulated, or spiculated margins | 1 |

Mass seen on a mammogram, circumscribed margins with no suspicious features, new, enlarging, or no priors to compare | 9 |

Multiple bilateral masses with no mass demonstrating suspicious features, no priors available or baseline | 1 |

Multiple bilateral masses with one dominant mass or one or more demonstrating suspicious features | 5 |

Focal asymmetry or symmetry seen on one view, no priors | 1 |

Focal asymmetry or symmetry seen on one view, new or enlarging | 1 |

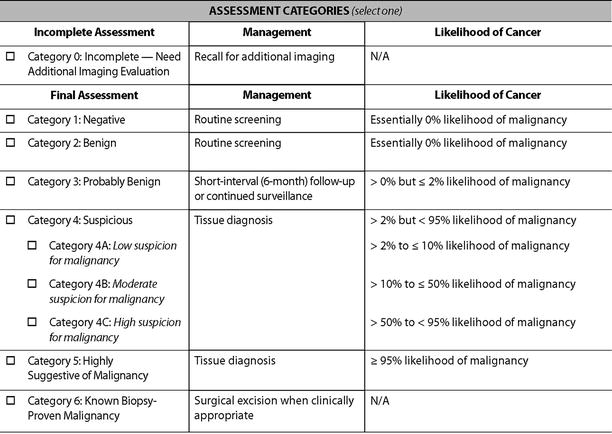

Table 7.3

Appropriateness of use of ultrasound following a palpable finding on a screening mammogram

Indication | Procedure rating for next exam to perform |

|---|---|

Woman 40 years or older, initial evaluation | 4 |

Woman 40 years or older, initial evaluation, mammographic finding is suspicious | 9 |

Woman 40 years or older, initial evaluation, mammographic finding is probably benign | 8 |

Woman 40 years of age or older, mammography findings benign (like lipoma) at site of palpable mass. | 2 |

Woman 40 years of age or older, mammography findings negative | 9 |

Woman 30 years or younger, initial evaluation | 9 |

Woman 30 years or younger, ultrasound findings probably benign: US short interval follow-up | 9 |

Woman aged 30–39 years, initial evaluation | 8 |

Ultrasound | 8 |

Diagnostic mammogram |

Indications [1, 3–13]

1.

Evaluation and characterization of palpable breast masses and other breast related signs and symptoms.

2.

Additional evaluation of abnormal findings seen on a mammogram or a breast MRI.

3.

Imaging modality of choice in women under the age of 30 years or those who are pregnant or lactating. Given the low incidence of breast cancer and to minimize exposure of the breast glandular tissue to diagnostic radiation.

4.

Evaluation of breast implants.

5.

For guidance of breast interventional procedures.

6.

Treatment planning for radiotherapy.

7.

Supplemental screening for occult breast cancer in defined population of women in whom MRI is not an option due to a contraindication or lack of access. These include women who are newly diagnosed with breast cancer or those who have a dense breast and are in addition at an elevated risk for breast cancer.

8.

To detect a mass associated with architectural distortion or suspicious microcalcifications when surrounded by dense glandular tissue.

9.

Assessment and biopsy guidance of abnormal axillary nodes such as in patients diagnosed with breast cancer.

The AIUM [American Institute of Ultrasound] practice and the American College of Radiology [ACR] guidelines have similar indications for the use of breast ultrasound with few notable exceptions. The AIUM does not recommend the use of breast ultrasound for breast cancer screening. The efficacy of sonography as a screening study for occult masses is an area for research; at this time, sonography is not considered a primary screening modality for breast cancer [1]. The ACR recommends supplemental use of ultrasound for breast cancer in a defined set of women who are at an elevated risk for breast cancer and in whom MRI is not an option [2, 10, 11].

Technical Aspects of Breast Ultrasound

Breast sonography is performed with a high-frequency linear array transducer operating at a center frequency of at least 10 MHz, with electronic adjustment of the focal zone. The highest frequency that is capable of satisfactory penetration to the depth of interest is desirable to obtain the best resolution; for very superficial lesions or lesions suspected to be in the dermis, standoff gel pad or a blob of gel and/or use of small hockey stick transducers is helpful. In special circumstances such as in deep lesions in large breasts or when a large abnormality is being assessed, lower-frequency transducers that allow better penetration can be used. The patient is positioned to minimize thickness of the portion of the breast being evaluated and to bring the area of interest within the optimal focal zone of the transducer [1, 2].

Breast ultrasound examination should be appropriately correlated with the indication for imaging be it a physical finding or a mammographic abnormality. If prior sonograms are available, comparison is needed to assess for interval change. Images should be as a standard practice obtained in two perpendicular planes with and without the use of calipers. The size of the lesion should be recorded and location of the lesions in relation to clock face and distance from the nipple has to be documented. The footprint of the transducer is usually 3.5–5 cm and can be used to assess distance from the nipple. The orientation of the lesion in the radial and anti-radial planes is notated on the images.

Breast Ultrasound as a Supplemental Modality to Diagnostic Mammography

The two most common indications for the use of breast ultrasound are for characterization of a mammographic mass and further assessment of an area of focal asymmetry that is identified on a mammogram. Sonographic assessment of these findings allows appropriate final categorization of abnormalities (Table 7.1).

Screen-Detected Breast Mass

Breast masses when multiple and bilateral are considered benign with a BI-RADSTM assessment of Category 2 and recommendation for annual screening mammography [16]. Such findings are encountered uncommonly and in one large series represented 1.7 % of screening mammograms [16]. Bilateral similar-appearing masses are often simple or complicated cysts and do not merit a recall. There were only two node-negative cancers among 1440 women in a series reported by Leung and Sickles which is less than the expected interval cancer rate. Recently Berg and others reported that multiple bilateral circumscribed masses are more common at whole-breast US and were seen in 135 of 2,172 women [6.2 %]. There were no malignancies identified in any of these cases at 2 years of follow-up [17]. Annual follow-up by ultrasound may be adequate in these cases if there is no mammographic correlate for a total of 2 years. The malignancy rate among solitary circumscribed masses (complicated cysts; clustered microcysts; circumscribed oval, round, gently lobulated masses) detected at US and with at least 2 years of follow-up has been shown to be low at 0.4 % [17].

The primary role of ultrasound for a finding of a screen-detected mass is to distinguish a simple cyst from a solid lesion. However, a significant proportion of mammographic masses represent a spectrum that ranges between these two findings. This range includes complicated cysts, clustered microcysts, and complex cystic masses.

Simple Cysts

A sharply demarcated anechoic lesion with posterior acoustic enhancement is characteristic of a benign cyst. A thin septa (<0.5 mm) may be seen within a simple cyst. When strict criteria for determination of a cyst are adhered to, the accuracy of ultrasound in making this distinction is 96–100 % [18]. Cysts constitute 25–37 % of all palpable or mammographically detected lesions [3, 19–21]. Simple cysts are epithelial lined and fluid filled that are round or oval shaped and represent dilated terminal ductal–lobular units secondary to obstructed ducts. Cysts are often sharply demarcated on mammography unless obscured by surrounding tissue. The epithelium can be bland or apocrine type; the latter is a tall cuboidal secretory epithelium that can give a fuzzy appearance to the inner wall of the cyst on high-resolution sonography [21]. Cysts are less common in postmenopausal women but may be seen in those women who are on hormone replacement therapy, and in this group they have been reported in 6–29 % [21]. Meticulous attention to gain setting is important to ensure that certain solid masses are not incorrectly diagnosed as cysts which can happen when the gain setting is set at too low. Such a misdiagnosis can happen with circumscribed cancers that have a markedly hypoechogenic internal echotexture. Malignant lesions that can have such an appearance include necrotic invasive ductal cancer, medullary cancer, mucinous cancer, and lymphomatous or metastatic lymph nodes. Metastatic nodes are distinguished by their typical location in the axilla or upper outer quadrant of the breast and some flow on Doppler ultrasound. Margin characterization is also helpful, with malignancies showing at least some focal irregularity; documentation of images without calipers is important so as not to obscure such distinguishing focal irregularities [4, 21].

Complicated Cysts, Clustered Microcysts, and Complex Cystic Masses

These are a common finding on ultrasound and include a spectrum ranging from a cyst with internal septations, clustered cysts, and those with internal echoes and/or intracystic masses [4, 21–25].

Complicated cysts are those with internal debris from cell turnover, bleeding, or infection. Only 2 of 868 lesions [0.23 %] that were thought to represent complicated cysts were proven malignant in multiple series [21]. Complicated cysts when seen with other similar lesions and/or simple cysts are appropriately categorized as benign findings; when solitary, they may be subjected to a short interval follow-up. The distinction is particularly challenging when a lesion is smaller than 4 mm: 21 % were characterized as solid masses in one series [21].

Finding of a fluid debris level or mobile internal echoes allows a confidant determination of a complicated cyst. In the ACRIN6666 trial, 6.1–7.4 % of complicated cysts demonstrated these features [10]. In a complicated cyst without these two features and in which the internal echoes are homogenous, distinction from a solid mass becomes more challenging. It has been reported that about 12 % of such lesions may be solid, and in multiple studies, about 3.1 % of such solid masses have been shown to be malignant [21]. Daly and others found only one cancer in a series of 243 [0.4 %] complicated cysts undergoing aspiration [22]. Presence of internal vascularity is an indication for biopsy since such a finding precludes a cyst. Elastography may also be helpful in distinguishing a benign complicated cyst from a solid mass.

Cystic dilatation of the acini of the terminal ductal-lobular unit leads to formation of clustered microcysts. These are most common in the perimenopausal women and reported in 2.4–5.8 % of women [21]. In the ACRIN6666 trial, there was one 4 mm node-negative invasive lobular cancer among 123 such lesions (0.8 %) [10]. Tissue harmonic imaging by reducing artifactual internal echoes may be helpful in characterizing a lesion as a cyst [26]. Spatial compounding is another tool that can help in this regard. By decreasing speckle and noise, there is better definition of internal structures. An improvement of spatial resolution leads to better recognition of small cysts; posterior acoustic enhancement becomes less apparent when spatial compounding is turned on [27].

These are cysts with walls and/or septations greater than 0.5 mm, intracystic masses or sold masses with cystic areas; such abnormalities are considered suspicious with a recommendation for biopsy. A malignancy rate as high as 36 % has been reported among complex cystic masses [21], although in the ACRIN6666 study no malignancies were found in 20 such lesions. The differential diagnosis of complex cystic mass appears in Box 7.1.

Box 7.1. Differential Diagnosis of Complex Cystic Masses

1. Fat necrosis |

2. Papilloma |

3. Intracystic carcinoma |

4. Abscess |

5. Evolving hematoma |

6. Galactocele |

7. Complex fibroadenoma |

8. Phyllodes tumor of the breast |

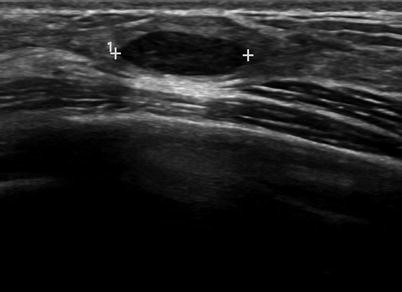

Solid Mass

A solid mass is characterized based on ultrasound features that allow a mass to be categorized in one of three groups: benign, probably malignant, or indeterminate. For a mass to be considered benign, one of three findings have to be present: intense uniform hyperechogenicity, ellipsoid shape with a thin echogenic capsule, and two to three gentle lobulations with a thin echogenic capsule (Figs. 7.2 and 7.3). The negative predictive value of intense uniform hyperechogenicity has been reported to be 100 %, a thin echogenic pseudo capsule was 99.2 %, ellipsoid shape was 99.1 %, and four or fewer gentle lobulations was 98.8 % [20].

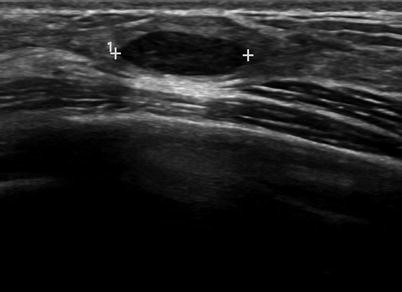

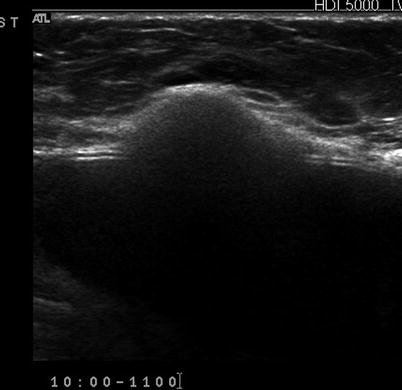

Fig. 7.2

An ovoid mass with a thin echogenic capsule consistent with a benign solid mass. Histological diagnosis: fibroadenoma

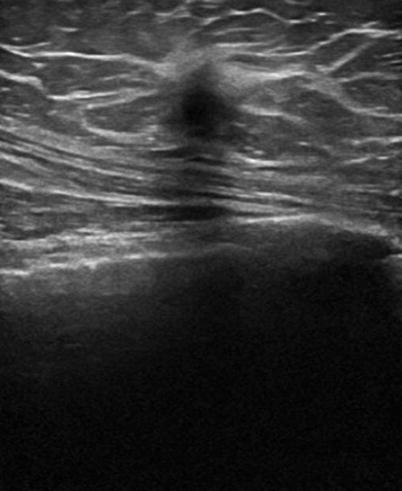

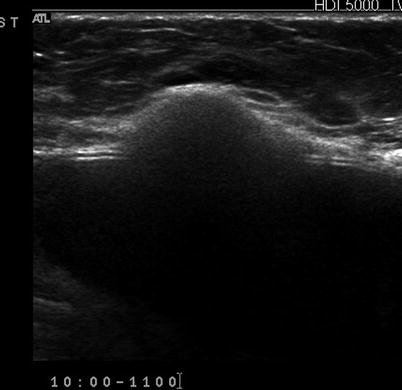

Fig. 7.3

An ovoid mass with a thin echogenic capsule and uniform isoechogenicity consistent with a benign solid mass. Histological diagnosis: lipoma

There are nine malignant features that have been described by Stavros and others; these include the following (positive predictive value for each of the malignant feature is within parenthesis): spiculation [91.8 %], a solid mass that is taller than wide [81.2 %], a mass with angular margins [67.5 %], one that demonstrates posterior acoustic shadowing [64.9 %], a mass that demonstrates a branching pattern [64 %], hypoechogenicity [60.1 %], calcifications [59.6 %], duct extension [50.8 %], and microlobulations [48.2 %]. A solid mass is initially interrogated for presence of a malignant features, and when absent, the previously described benign features are sought. If benign characteristics are seen, a solid mass is classified as being benign. Solid masses which do not demonstrate malignant or specific benign features are then classified as indeterminate with a recommendation for tissue diagnosis [20] (Figs. 7.4, 7.5, 7.6, and 7.7).

Fig. 7.4

A hypoechogenic mass that is taller than wider. Histological diagnosis: invasive ductal cancer

Fig. 7.5

A hypoechogenic mass with angular margins. Histological diagnosis: invasive ductal cancer

Fig. 7.6

A hypoechogenic mass with a branching pattern. Histological diagnosis: invasive ductal cancer

Fig. 7.7

A hypoechogenic mass with a duct extension. Histological diagnosis: ductal carcinoma in situ

Description of Benign Features [21]

Intense and uniform hyperechogenicity refers to markedly hyperechoic tissue compared to the echogenicity of fat. Hyperechogenicity should be uniform and usually corresponds to fibrous tissue; this criterion cannot be applied to masses that have areas of decreased echogenicity within other than fat lobules or ducts or terminal lobular ductal units that are larger than 4 mm.

An ellipsoid shape or a mass that is taller than wider refers to a sagittal and transverse diameter that is greater than the anteroposterior dimensions. A thin echogenic capsule indicates a slow-growing lesion; in order to demonstrate this finding in its entire extent, the transducer will have to be angled and studied in real time in multiple planes. Gentle lobulations are gently curving, smooth, and few in number, three or less, as opposed to microlobulations that are a feature of a malignant mass. Since some purely intraductal cancers may have a thin echogenic capsule and a few malignant ellipsoid masses with gentle lobulations do not have a thin echogenic capsule, using these criteria in combination improves the accuracy of characterizing breast masses [20].

Description of Malignant Features [20]

Spiculation is seen as alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic lines that radiate from the surface of a mass. The appearance of these spicules is modified depending on whether hyperechoic tissue surrounds the mass. A mass that is taller than wider is when any part of a mass is greater in its anteroposterior dimension than in its sagittal or transverse dimension indicating that the tumor is aggressive and transgressing the normal tissue planes of the breast. Angular margins refer to the junction between the hypoechoic central portion of the solid mass and the surrounding tissue; this interface may be acute, obtuse, or 90°. Branching pattern in a solid mass is akin to duct extension and refers to presence of multiple broad-based projections extending from the surface of the mass. Marked hypoechogenicity is a finding described in comparison to the surrounding tissue. Duct extension is said to be present when there is radial extension of the tumor either within or along a duct coursing in the direction of the areola. Posterior acoustic shadowing is considered present even when mild or present behind a small portion of the mass. Calcifications refer to punctate calcifications seen in a mass; these are more suggestive of a malignant process: calcifications are more apparent when a mass is intensely hypoechogenic. Microlobulations refer to the presence of 1–2 mm lobulations on the surface of a solid mass.

Using the previously described criteria, Stavros and others, in a series of 750 solid masses, characterized 625 masses as benign (83 %) and 125 as malignant. Mammography did poorly compared with sonography in characterizing a malignant mass. Mammography did not identify 24/125 malignant masses that were correctly characterized by sonography; an additional five malignant masses were classified as probably benign based on mammographic features [20]. The high negative predictive value of sonography in excluding malignancy in a solid mass was proven in this study where only two [0.5 %] of the 426 solid masses that were characterized as benign were malignant, one of which was a metastasis from lung cancer [20]. The malignancy rate among masses classified as malignant was 73 % and the cancer rate in the group considered as indeterminate was 12.3 % [20]. Screen-detected mammographic mass can sometimes be sonographically occult [28]. The accuracy of ultrasound in being able to distinguish benign from malignant masses has been shown in several other studies with similar results [3, 19, 29–33]. The value of sonography in diagnosing malignant palpable masses was reported in a multi-institutional study of palpable masses undergoing sonography; all 293 of 616 palpable masses were correctly characterized as probably malignant by sonography [31]. In a retrospective series of 162 masses undergoing biopsy, three most reliable discriminatory features of a benign mass were round or oval shape (67/71, 94 % benign), circumscribed margins (95/104, 91 % benign), and a width to anteroposterior dimension >1.4 (82/92, 89 %) [19]. Morphological features most suggestive of a malignant mass were an irregular shape (19/31, 61 %), width to anteroposterior ratio of <1.4 (28/70, 40 %), microlobulations (4/6, 67 %), and spiculation (2/3, 67 %). Like others, these investigators found that the internal echotexture of a mass and presence of posterior acoustic enhancement does not help in the distinction between a benign or malignant mass. Uniform hyperechogenicity, although a very useful feature in characterizing a mass as benign, is not very helpful since it is a finding uncommonly encountered in a mass [30, 32]. Some of the descriptors of a mass such as a thin echogenic capsule is a finding that may be subject to considerable interobserver variability [19, 30]. If the three of the most useful sonographic features of a benign solid mass were strictly applied, the positive biopsy ratio would potentially increase from 23 to 39 % [19]. Using benign mass criteria of an oval or lobulated shape; circumscribed margins; internal echogenicity of isoechoic, mildly hypoechoic, or hyperechoic; and a mass that was wider than tall and a non-shadowing mass or one with increased posterior echoes, 144 of 844 solid masses were categorized as benign; there was only one malignant mass in this group, indicating that biopsy avoidance is a feasible alternative when clearly benign sonographic features are demonstrated in a solid mass [19, 30].

Focal Asymmetry

The American College of Radiology has provided separate definitions in the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) lexicon for focal asymmetric density and asymmetric breast tissue. A focal asymmetric density is described as “… a density that cannot be accurately described using the other shapes. It is visible as asymmetry of tissue density with a similar shape on two views, but completely lacking borders and the conspicuity of a true mass. It could represent an island of normal breast, but lack of specific benign characteristics may warrant further evaluation. Additional imaging may reveal a true mass or significant architectural distortion” [34].

“Asymmetric breast tissue is judged relative to the corresponding area in the other breast and includes a greater volume of breast tissue, greater density of breast tissue or more ‘prominent ducts.’ There is no focal mass formation, no central density, no distorted architecture, and no associated calcifications.” A focal asymmetric density should be further evaluated to distinguish it from benign asymmetric tissue and to exclude an underlying mass [34]. Focal asymmetry of the breast can be a mammographic sign of breast cancer [34–39]. Sonography is indicated only after a thorough mammographic workup of focal asymmetry; once the finding is determined to be real based on such a workup, sonography is appropriate to exclude an underlying mass [36]. In the absence of a palpable finding, or a suspicious associated mammographic finding such as microcalcifications or distortion, a negative sonogram can be reassuring in a patient where focal asymmetry is seen on a baseline mammogram or when prior mammograms are not available. A final assessment category of BI-RADS 3 with a recommendation for a short interval follow-up is appropriate since the likelihood of cancer in such cases is less than 1 % [36]. On the other hand, if the finding is new or enlarging, tissue diagnosis is indicated despite lack of an associated physical finding and associated suspicious mammographic features despite absence of a sonographic finding. In those women where the focal asymmetry has been stable for 1 year, a BI-RADS 3 assessment with annual follow-up for 1–2 years is appropriate [36]. The negative predictive value of sonography in excluding cancer was 89.4 % in one series of 36 patients who underwent biopsy [35]. Ultrasound demonstrated a finding in 26 of 36 cases: all 5 solid masses with probable malignant features were invasive ductal cancers. Developing asymmetry has a 13–27 % likelihood of malignancy, and this depends on whether this finding was identified on a screening or a diagnostic mammogram [39].

Breast Ultrasound in the Symptomatic Patient

Palpable Abnormalities of the Breast

The accuracy of clinical evaluation of a palpable abnormality of the breast is limited; signs of breast cancer are not distinctive. It is not possible to reliably distinguish cysts from solid masses on physical examination [34, 35]. A majority of palpable abnormalities of the breast are caused by benign abnormalities especially in women under the age of 40 years. Malignancy has been reported in 4–5 % of patients with breast symptoms and even among palpable lesions undergoing biopsy [40–43]. The role of mammography in patients with palpable breast lumps is to show a benign cause for the palpable abnormality, which, although uncommon, avoids further intervention (calcified involuting fibroadenoma, lipoma, oil cyst, galactocele, and hamartoma), to support earlier intervention for a mass with malignant features, to screen the remainder of the ipsilateral and contralateral breast for additional lesions, and to assess the extent of malignancy when cancer is diagnosed [44].

Mammography has limitations in assessing women with palpable abnormalities; a false-negative rate of mammography for breast cancer in patients with palpable abnormalities of the breast can be high and reported false-negative rates range from 16.5 to 40 % [19, 45]. It is standard practice to assess a palpable abnormality with mammogram and ultrasound with some few exceptions noted previously. Addition of sonography in the imaging evaluation leads to a high degree of accuracy in detecting underlying abnormalities. Multiple studies have shown that the false-negative rate for a combined mammographic and sonographic evaluation varies from 0 to 2.6 % [40–44].

Sonography in addition may obviate the need for intervention by showing benign causes of palpable abnormalities such as cysts, benign intramammary lymph nodes, extravasated silicone, and superficial thrombophlebitis of Mondor’s disease of the breast [6, 45–49] (Figs. 7.8a, b and 7.9). Sonography is also able to characterize palpable lesions obscured by dense tissue on mammograms. Moss et al. reported that sonography increased cancer detection by 14 % in symptomatic patients who were evaluated with both mammography and sonography [50]. In a retrospective analysis of 293 palpable malignant lesions, sonography detected all cancers; 18 (6.1 %) of these 293 cancers were mammographically occult [31]. In a consecutive series of 123 cases with palpable breast thickening, sensitivity of sonography for detection of invasive cancer was 100 % [51].

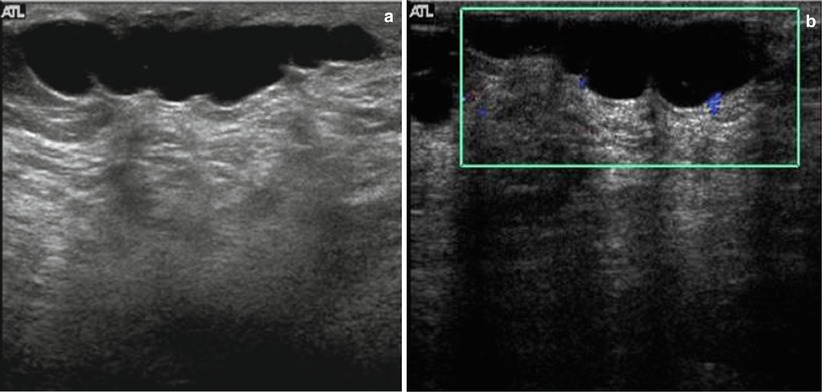

Fig. 7.8

(a) Mediolateral view of the left breast demonstrates a focal asymmetry corresponding to the palpable lump. (b) A palpable lump that is sonographically determined to be in the dermis and hence benign. A complex cystic abnormality consistent with an infected epidermal cyst. Color Doppler interrogation shows increased peripheral vascularity suggestive of inflammation

Fig. 7.9

A palpable lump in a patient with a silicone implant reveals it to be caused by localized extravasation of silicone producing a “snow storm” appearance, classic of extracapsular implant rupture

Is Follow-Up of Palpable Solid Masses an Option?

An assessment of a probably benign finding with a recommendation for a short interval follow-up has not been validated for masses in the breast when they are palpable [52–54]. Sickles criteria for such categorization specifically excluded lesions that were palpable. One of the criticisms of the publication of findings on ultrasound characterization of solid masses by Stavros was that the study cases included both palpable and nonpalpable masses [20]. Over the past few years, there has been increasing support for the fact that palpability of solid breast masses need not be criteria for tissue diagnosis [55–60]. Some breast imagers categorize solid palpable breast masses with otherwise benign sonographic features as BI-RADS 4A [2–10 % chance of malignancy] with a recommendation for tissue diagnosis [61] mainly due to the palpability factor. One such series of 41 cases had no cases of cancer [55]. In another series of 312 such masses undergoing biopsy, 310 were benign [99.4 %] lending scientific support for follow-up and biopsy avoidance [56]. Others have also reported that a follow-up protocol for palpable solid breast masses has shown similar results. In a series of 157 palpable breast masses, 112 were followed with interval increase in size in six at follow-up all were proven benign at biopsy. Forty-five masses underwent biopsy without follow-up with no malignancy identified [57]. In yet another larger series of patients in whom noncalcified solid breast masses were followed, there was a malignancy rate of 0.2 % [1 of 448 masses] which was biopsied based on interval enlargement at follow-up [58]. When following solid masses particularly those that are palpable, careful inspection of morphologic features is, however, important. Of these features particularly the margins need to be assessed for irregularities; it is not uncommon for masses that may appear mammographically benign to have ill-defined margins on ultrasound for certain special types of cancers such as mucinous cancer (Fig. 7.10a, b). Also, certain cancers that are hyperechoic and initially put on a surveillance protocol on follow-up may be determined not to exhibit strictly benign features, particularly in the case of hyperechoic masses that on close inspection demonstrate internal inhomogeneity (Fig. 7.11a–c).