With the increasing use of skin-sparing mastectomies, oncoplastic procedures, and immediate reconstructions, the autogenous latissimus breast reconstruction has experienced a resurgence of interest. The “autogenous latissimus flap” refers to self-derived composite of muscle, fat, and skin. This concept is based on the ability of the latissimus muscle to “carry” fat on its surface. This composite of fat and muscle is extremely helpful in several ways. It adds volume, which may be adequate to replace the breast shape without using an implant. It is also an ideal local tissue replacement for oncoplastic procedures and the correction of irradiation fibrosis. The autogenous latissimus flap further serves as a “backup” flap for microvascular and TRAM flap breast reconstructions, when there is partial or complete flap loss. Finally, the autogenous latissimus flap can be used to create an aesthetic breast both with and without an implant. The latissimus muscle is an “expendable” muscle, in the sense that its loss of function is seldom noticed. The primary concern about functional loss is in the motion of “pushing off” with a ski pole.1

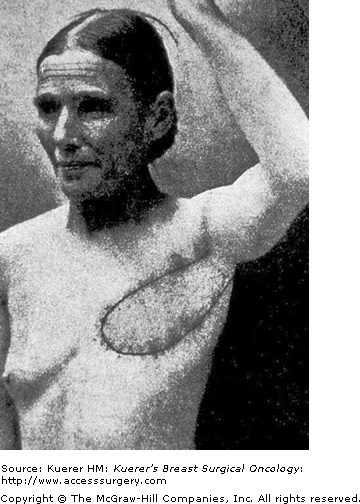

Iginio Tansini, a professor of surgery at the University of Padua in Padua, Italy (Fig. 80-1), described the first latissimus musculocutaneous flap in 1896.2 He used the island latissimus flap to reconstruct the radical mastectomy defect with “like” tissue (Fig. 80-2). “Besides healing the wound … the flap is of considerable thickness and succeeds in providing an even better repair to the loss of matter, substituting the latissimus dorsi muscle for the pectoralis major muscle.”3 Tansini’s contribution of the concept of the “island” latissimus flap, which “carried” the overlying skin, was a new concept. His goal was to repair the radical mastectomy defect by replacing both the lost skin and the pectoralis muscle. This “Tansini Method of Mastectomy” included radical removal and replacement of most of the breast skin and the pectoralis major muscle, and replacing the lost tissue with the latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap.3 In Europe this became the most common method of obtaining a healed wound in the radical mastectomy defect during the first 2 decades of the 20th century.

In his grand tour of Europe in 1920, as America’s first professor of surgery and most eminent surgeon, William S. Halsted objected to the use of a flap reconstruction at the time of mastectomy because of his fear that the latissimus flap might obscure diagnosis of breast cancer recurrences. Halsted advocated the use of skin grafts or secondary epithelialization for mastectomy defects, rather than a flap, so that recurrences could be recognized promptly. As he said in his 1907 paper, probably in reference to Tansini, “I should not care to say beware of the man with the plastic operation …. But to attempt to close the breast wound more less regularly by any plastic method is hazardous, and in my opinion to be vigorously discountenanced.”4 The Halsted method of radical mastectomy prevailed, and the flap reconstruction method of Tansini was abandoned by 1920. The surgical world was not ready for modern flaps.5

In the 1970s Nevin Olivari in Cologne, John McCraw in San Antonio, and Wolfgang Muhlbauer in Munich independently described the latissimus myocutaneous flap for chest wall reconstruction.6-8 Schneider, Hill, and Brown from Atlanta first described the “standard” latissimus-implant breast reconstruction, and Bostwick, Vasconez, and Jurkiewicz first described the use of the latissimus reconstruction method for the radical mastectomy deformity.9,10 In 1985 Christoph Papp of Austria described the “autogenous” latissimus flap, which “carried” fat on the surface of the latissimus muscle, in order to recreate the contour of the breast without an implant. Papp and McCraw later reported an extensive combined experience, in which they also modified the standard latissimus flap design to include adipose tissue, and coined the term “autogenous latissimus” flap.11 Many authors have reported success with this autogenous or “extended” myocutaneous flap, which eliminates the need for an implant, and can permit a totally autogenous reconstruction. This flap is particularly applicable to both small and large oncoplastic partial mastectomy defects, as well as Poland deformity.12,13

Advances in the application of the latissimus flap technique over the past 2 decades have demonstrated the utility of this reconstruction in primary and salvage flap breast reconstructions, both with and without an expander or permanent implant.14 Endoscopic technology can also facilitate the dissection in the axilla and, in some cases, allow shorter incisions for flap harvest. It is now recognized that the skin-sparing mastectomy with immediate reconstruction is oncologically sound. In practice the result of the reconstruction is more dependent on the type of mastectomy, rather than the type of flap. The quality of the result of the autogenous latissimus reconstruction is primarily dependent upon the type of mastectomy, so the more deforming the mastectomy, the more compromised is the reconstructive effort. Good or excellent results can be predictably achieved with skin-sparing mastectomies. If a radical mastectomy or a comparably deforming Patey mastectomy is done, good results are seldom possible.15

The original (1977) latissimus myocutaneous flap incorporates a large implant, in order to provide both shape and volume.16,17 The latissimus muscle is primarily used to provide coverage for the implant, and the skin paddle is inset transversely into the modified mastectomy scar. As a better method of breast shaping, the transversve rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap was introduced in 1982 as a completely autogenous reconstruction, which usually did not require an implant for volume replacement.18 By 1985 the autogenous latissimus reconstruction became a good choice for reconstruction, because an implant was usually not needed to provide the breast shape. This offered a new method for reconstruction of the partial mastectomy, the bilateral mastectomy, the Poland chest wall deformity, or in reconstruction of small breasts.19-21

Today, one of the most frequent indications for using the autogenous latissimus breast reconstruction is as an alternative to the TRAM flap, when patients are either too thin, too obese, or because the supplying vessels have been injured by irradiation or previous abdominal surgery. Patients may choose to have the autogenous latissimus reconstruction because of the predictable results, limited discomfort, and the shorter recovery time compared to the TRAM flap breast reconstruction.22 Patients may choose not to have the TRAM flap reconstruction because they want to avoid abdominal surgery, scars, and possible abdominal wall weakness. Also, many active women, such as women with busy jobs or mothers with young children, may wish to avoid the longer recovery required for TRAM flap reconstruction. The latissimus flap is an option when free tissue transfer is not feasible because of patient anatomy, surgeon’s choice, or lack of institutional resources. It also provides a good alternative to the free tissue transfer options, such as the muscle-sparing TRAM flap or the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) free flaps, when skin replacement is not a major issue. Finally, the latissimus flap is useful as a “salvage” or backup flap after failed implant or TRAM reconstructions, or after failed lumpectomy. It is the first line of defense for the treatment of radiation injuries, since it supplies soft tissue coverage as well as new vascularization to the neck, chest, and breast.

Despite the utility of the latissimus in breast reconstruction, certain patients may not be candidates for this method. Previous axillary dissection with radiation may not permit safe dissection of the pedicle, or it may increase the risk of vascular insufficiency or vascular injury. Previous division of the thoracodorsal vascular pedicle in a mastectomy can represent an absolute contraindication. Other relative contraindications include patient refusal of an implant when it is needed for volume and projection, and patient desire to avoid any surgery on the back. The need for postoperative irradiation may also influence the timing of the reconstruction or affect the decision to use an implant. Most patients who elect to have latissimus flap reconstruction can return to such pursuits as golf and tennis, and approximately 80% of patients note no change in shoulder mobility and strength.23 Patients with shoulder arthritis, or professional athletes who need full shoulder function, are not good candidates for the latissimus breast reconstruction.

The latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction provides a predictable method of supplying vascularized muscle and skin to the breast area in a single operative procedure. A relative disadvantage includes the need for an implant to augment the breast volume, but in patients who have adequate fat on the surface of the latissimus muscle, an implant is seldom required. When you can “pinch an inch,” usually 600 mL of fat can be transposed with the muscle, which can provide symmetry with the opposite breast without an implant. Even in very thin patients with small breasts, 200 to 300 mL of volume can be transferred from the back to the breast. The TRAM flap, by comparison, provides more skin replacement, which may be needed in the case of very deforming mastectomies. The deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap, which was introduced as a method of breast reconstruction by Koshima and Soeda in 1989, is popular with patients because it provides abdominal skin and fat without harming the rectus abdominis muscle.24 DIEP free flaps offer predictably excellent results, but it is necessary to have specially trained surgeons and a most sophisticated operative team.

The latissimus dorsi muscle has a dual blood supply from both the thoracodorsal branch of the subscapular artery and the posterior paraspinous perforators. The dominant vascular supply to the muscle is via the thoracodorsal artery and vein, which are usually 2 mm in diameter (Fig. 80-3). The axillary artery gives off the subscapular artery high in the axilla, and the thoracodorsal artery branches off the subscapular artery. The serratus branch splits from the thoracodorsal artery to course on the surface of the serratus anterior muscle. The serratus branch exits from the thoracodorsal artery approximately 10 cm below the subscapular artery. The serratus branch must be carefully identified, so that the thoracodorsal artery is not mistakenly divided during the dissection. The thoracodorsal artery passes near the lateral border of the latissimus muscle, approximately 2 to 3 cm inside the lateral border of the muscle. Within the muscle the thoracodorsal artery splits into 2 terminal vessels. This parallel blood supply makes it possible to split the latissimus longitudinally into medial and lateral segments, which can be moved independently for small defects. The skin overlying the latissimus muscle is supplied by numerous muscular perforating vessels, which exit the surface of the muscle to supply the overlying fat and skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree