From radical mastectomy to breast-conserving surgery (BCS), the last 35 years have witnessed a fascinating evolution in the role of surgery in the treatment of breast cancer. For almost a century, Halsted’s mastectomy was the treatment of choice for all stages of breast cancer. However, multiple prospective, randomized trials with more than 20 years’ follow-up have since documented that breast-conserving operations followed by whole-breast irradiation offers survival outcomes equivalent to mastectomy in appropriately selected patients.

Breast-conserving surgery is defined as the complete removal of the tumor with a concentric margin of surrounding healthy tissue with maintenance of acceptable cosmesis, and should be followed by radiation therapy to achieve an acceptably low rate of local recurrence. Appropriate selection of patients, adequate surgery, and breast irradiation are important components of successful breast-conserving therapy (BCT). Surgical evaluation of the axillary lymph nodes should be performed in patients undergoing BCT for invasive carcinoma, but the status of the axilla does not influence the decision on BCS. Incorporating oncoplastic techniques may be considered to optimize cosmetic outcome in select patients.

Six modern, prospective, randomized trials have demonstrated that breast-conserving therapy (lumpectomy followed by radiation) offers survival rates equivalent to mastectomy (Table 61-1)1-7; however, when negative margins are not achieved or when radiation therapy is not pursued, breast conservation is associated with higher rates of local recurrence (Tables 61-1 and 61-2).1,2,8-14 Until recently, the impact of local recurrence on survival remained unclear. In 2005, the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) published the results of a large meta-analysis combining all individual patient data for 42,080 women who collectively took part in 78 treatment comparisons (more vs less surgery, more surgery vs radiotherapy, radiotherapy vs none) to determine the impact of local recurrence on survival. Specifically, among 10 breast-conservation trials included in the EBCTCG analysis (7311 women), postoperative radiation treatment (XRT) was associated with a statistically significant reduction in local recurrence in each individual trial. Furthermore, postoperative XRT was associated with an overall absolute reduction in local recurrence of 19% at 5 years, an absolute reduction in breast cancer–specific mortality of 5.4% at 15 years, and similar reductions in 15-year overall mortality. They concluded that optimal locoregional control does confer a quantifiable survival benefit in early-stage breast cancer and as such the importance of local control is no longer a matter of debate.15

| Clinical Trial | Dates | N | TNM | Margin Status | XRT Boost | Follow-Up (Years) | LOCAL RECURRENCE (%) | OVERALL SURVIVAL (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mx | BCT&XRT | Mx | BCT&XRT | |||||||

| NSABP B061 | 1976-1984 | 1217 | ≤4 cm N0N1 M0 | Tumor free | Yes | 20 | 10.2 | 14.3 | 47.2 | 46.2 |

| EORTC5 | 1980-1986 | 874 | ≤5 cm N0N1 M0 | 1 cm | Yes | 8 | 10 | 15 | 64 | 66 |

| Danish Breast Cancer Group4 | 1983-1987 | 859 | Any size N0N1 M0 | Grossly free | Yes | 6 | 4 | 3 | 82 | 79 |

| National Tumour Institute, Milan2,3 | 1973-1980 | 701 | ≤2 cm N0N1 M0 | Wide free | Yes | 20 | 2.3 | 8.8 | 41.2 | 41.7 |

| National Cancer Institute, US5 | 1979-1987 | 247 | ≤5 cm N0N1 M0 | Grossly free | Yes | 10 | 10 | 18 | 75 | 77 |

| Institute Gustave-Roussy France6,7 | 1972-79 | 179 | ≤2 cm N0N1 M0 | 2 cm | Yes | 14.5 | 11 | 11.4 | 65 | 72 |

| Median Follow-Up (yr) | Local Recurrence with XRT (%) | Local Recurrence without XRT (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSABP B-061 | 12.5 | 10 | 35 |

| Veronesi et al2 | 9.1 | 5.8 | 23.5 |

| Renton et al8 | 6.1 | 13 | 35 |

| Clark et al9 | 7.6 | 11.3 | 35.2 |

| Forrest et al10 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 24.5 |

| Liljegren et al11 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 24 |

| Malmstrom et al12 | 7 | 4.4 | 13.3 |

| Holli et al13 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 18.1 |

| NSABP B-2114 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 16.5 |

For BCT to be successful, 3 conditions must be met: It must be possible to (1) achieve negative surgical margins while maintaining cosmesis of the breast, (2) safely deliver radiation therapy, and (3) promptly detect local recurrence. Careful patient selection is important to ensure a low rate of local recurrence as well as acceptable cosmetic outcome. Contraindications to BCT are listed in Table 61-3.

| Absolute contraindications |

| • Multicentric disease |

| • Diffuse malignant-appearing microcalcifications |

| • Persistent positive margins after reasonable attempts to conserve the breast |

| • Need to deliver radiation during pregnancy |

| • Previous irradiation |

| Relative contraindications |

| • History of scleroderma |

| • Active systemic lupus erythematosus |

| • Unfavorable tumor size to breast size ratio |

Patient factors, such as young age, have been associated with an increased risk for local failure after BCT or after mastectomy. However, the EBCTCG found that the absolute effects of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery (generally with axillary clearance) for node-negative disease were greater in women less than 50 years old compared to women more than 50 years old; therefore, young age alone should not preclude breast conservation. A number of tumor factors, such as size and involvement of axillary lymph nodes, that are strong predictors of the risk for distant recurrence are not associated with the risk for recurrence in the breast. Histologic tumor type also is not a risk factor, and studies have shown that recurrence rates after excision of infiltrating lobular carcinoma to negative margins do not differ from those after excision of infiltrating ductal tumors. Most studies also indicate that histologic grade is not predictive of recurrence. Some studies have identified lymphatic invasion at the primary tumor site as a risk factor, but this has also been shown to be a risk factor for local recurrence after mastectomy.

For the older patient, controversy exists as to whether or not XRT can be safely omitted after breast conservation.16 In 2004, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) reported that women more than 70 years of age with estrogen receptor–positive cancers of smaller than 2 cm treated with lumpectomy and tamoxifen without XRT experienced a 3% increase in the risk of local recurrence.17 Yet, this increase in local recurrence did not translate into a decrease in time to distant metastases or overall survival. The EBCTCG also failed to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in breast cancer–specific mortality or overall mortality for women more than 70 years old undergoing conservative surgery plus radiotherapy versus surgery alone at 15 years (2.8% vs 2.9%, and 30.4% vs 28.9%, respectively).15 These data suggest that individualizing the decision about XRT in older women based on tumor characteristics and physiologic age rather than chronologic age should be considered.

A family history of breast cancer does not increase local failure rates. The introduction of specialized surveillance for women with a strong family history of breast cancer or a known BRCA mutation has increased the likelihood that breast cancer will be detected at a stage suitable for breast conservation. In women with mutations of BRCA1 or BRCA2, the risk of new second primary cancers is increased in both breasts, but the risk of local failure does not seem to be elevated.18 A recently published case-control series evaluated the outcome of BCT and estimated the 10-year in breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) risk to be equivalent between sporadic controls and mutation carriers (9% vs 12%, hazard ratio = 1.37; p = .19). However, on multivariate analysis, mutation status was an independent predictor of recurrence in women with intact ovaries (hazard ratio = .99, p = .04).19 Other studies reporting an increased risk of IBTR in mutation carriers have median follow-up times greater than 7 years, suggesting that these events are new second primary cancers. Although these findings sound a cautionary note for young mutation carriers considering BCT (especially those with intact ovaries), mutation status alone is not an absolute contraindication to BCT.20-23

Patients with a history of autoimmune diseases such as scleroderma, systemic or discoid lupus, and dermatomyositis may have increased sensitivity to radiation resulting in abnormal fibrosis, which may compromise the cosmetic outcome. Such conditions are not absolute contraindications to BCT, but rather are dealt with in a case-by-case manner. Whether other connective tissue diseases are associated with an increased risk of acute or late skin complications is controversial. A history of mantle radiation for Hodgkin disease may interfere with the conventional radiation therapy for overlapping of the radiation fields. Again, feasibility of BCT should be evaluated in a case-by-case manner with the consideration of a possible increase risk of second primary and contralateral cancers.24

There is no definite tumor size limitation to BCS as long as excision with clear margins can be achieved with acceptable cosmesis (favorable breast size to tumor size ratio). In an effort to increase the number of patients eligible for breast conservation, the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to shrink the primary tumor before surgical therapy has been studied.25 In a large randomized trial, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) protocol B-18, 1523 patients with tumors of any size were randomized to receive 4 cycles of doxorubicin (A) and cyclophosphamide (C), either preoperatively or postoperatively.26 All patients over age 50 received tamoxifen. A reduction in tumor diameter of 50% was noted clinically in 80% of the patients, and in 37%, no tumor could be felt after chemotherapy. Only one-fourth of the patients thought to be complete responders, however, had no tumor identified microscopically after surgery, and the rate of breast conservation increased by only 8%, from 60% to 68%. In a subsequent study, the addition of docetaxel to AC treatment preoperatively increased the clinical complete response rate from 40.1% to 63.6% (p < .001) and the pathologic complete response rate from 13.7% to 26.1% (p < .001).27 Despite this increase in response rate, the use of BCT did not differ between patients receiving preoperative AC and those receiving AC plus docetaxel (Taxotere). This is probably because of the inability of the physical examination and imaging studies to reliably predict the degree of pathologic response. To date, neoadjuvant therapy has not been shown to improve survival in comparison with therapy given postoperatively.

Multicentricity (ie, 2 separate cancers in different quadrants of the same breast) is an important contraindication to BCS. It has been suggested that if 2 lesions are close enough then they can be excised through a single incision as a single specimen with clear margins and acceptable cosmesis, the BCT may be considered. Historically, it was believed that extensive intraductal component (EIC) was associated with an increase risk of IBTR; however, subsequent data has shown that when EIC-positive tumors are excised to negative margins, local recurrence rates are comparable to those seen in EIC-negative tumors.28 As such, no particular volume of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) within the primary lesion should preclude BCS.

Breast cancer treatment is becoming more conservative in each of its multiple aspects, including medical therapy, radiation therapy, and breast surgery. The goal of this conservative approach is to combine optimal oncologic outcome with optimal cosmetic outcome. The majority of women with T1 and small T2 (smaller than 3 cm) cancers are suitable candidates for breast conservation. With oncoplastic surgery, larger tumors can be treated by BCT if the primary tumor can be excised adequately with clear margins and acceptable cosmesis. By combining sound principles of surgical oncology with those of plastic surgery, oncoplastic surgery can extend breast-conservation possibilities and is gaining acceptance as a useful tool in breast surgical oncology.

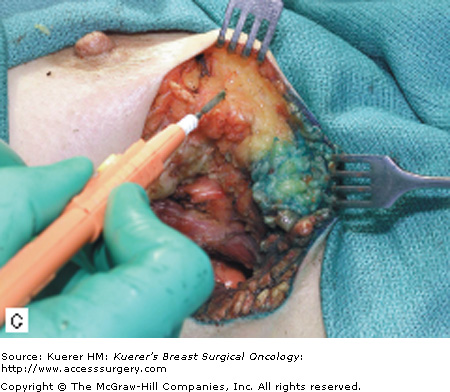

The surgical term “breast-conserving therapy” encompasses a range of procedures including quadrantectomy (segmentectomy), lumpectomy (tumorectomy, tylectomy), partial mastectomy, and many other definitions found in the literature. The quadrantectomy, first described by Veronesi et al, is an en bloc resection of the breast parenchyma, the overlying skin, and the underlying pectoralis fascia. It is typically performed through a long radial incision and removes a larger volume of breast tissue than other approaches, typically incorporating at least a 2-cm margin of normal tissue around the lesion (Fig. 61-1A, B).29 The anatomic basis of the quadrantectomy is that the ductal system of the breast is made up of 10 to 15 relatively independent sets of radially branching ducts and lobules. The pathologic basis is that the intraductal spread of cancer cells occurs relatively frequently along the ductal unit and, therefore, it is necessary to excise the entire portion of the ductal tree harboring the cancer. These concepts are supported by pathologic studies that demonstrate that breast cancer, both invasive and in situ carcinoma, is often limited to a single quadrant of the breast,30 and by the observation that DCIS often presents as microcalcifications extending along ducts of the breast. Once the specimen is removed, to obtain a better cosmetic result the breast parenchyma may be detached from the overlying skin and/or the underlying fascia of the pectoralis major over a distance of 1 cm (Fig. 61-1C). Mobilizing the breast in the deep and superficial plane facilitates reapproximation of the breast parenchyma and minimizes retraction or distortion of the breast (Figs. 61-1C, D).

Figure 61-1

Quadrantectomy technique. A. Elliptical radial skin incision for a cancer in the outer-upper quadrant. B. En bloc resection of the breast parenchyma, the skin ellipse, and the pectoralis fascia. C. The breast parenchyma may be detached from the overlying skin and/or the underlying fascia of the pectoralis major and then reapproximated. D. After the reapproximation of the breast parenchyma the skin is sutured.

In the lumpectomy, the excision is less generous with respect to quadrantectomy. The volume of breast tissue removed is usually 1 cm surrounding the palpable or nonpalpable cancer.31 The skin incision should be placed directly over the tumor whenever possible (Fig. 61-2A); this approach minimizes “tunneling” through uninvolved tissue planes, maximizes exposure, and thereby improves the odds of an adequate tumor excision with negative margins at the first operation. The incision should be of adequate size to allow complete tumor excision under direct vision; small incisions made with the goal of optimal cosmesis too often result in piecemeal tumor excision requiring reoperation to achieve adequate margins. An adequate skin incision is made, going just deep to the dermis. Skin flaps are then elevated in all the anatomical direction for about 1 cm, facilitating the exposure of the specimen (Fig. 61-2B). The excision is then carried out with the purpose of having 1-cm grossly free margins around the tumor (Fig. 61-2C). Closing the breast tissue in layers is controversial. It may cause retraction and dimpling of breast tissue and skin, but, if possible, it minimizes seroma formation and speeds healing. The skin is then sutured in layers with a running subcuticular monofilament suture.

The first goal of breast conservation is to excise an adequate amount of tissue to minimize risk of local recurrence. Margin status correlates with local failure and as such is an important predictor of residual disease after BCS. However, the appropriate extent of surgical resection needed to minimize this risk remains controversial and there is a lack of consensus regarding optimal method of margin assessment. This represents one of the ongoing “great debates” in breast cancer management.

For palpable lesions, gross inspection of the specimen at the time of removal permits identification of positive or close margins and immediate reexcision, if appropriate. This will decrease the need to return to the operating room for reexcision.32 Immediate margin assessment with cytologic touch prep analysis can identify the presence of tumor at the cut margin; however, this method cannot identify close margins and does not guarantee the absence of microscopic tumor on permanent sections. Precise marking and inking of the specimen allows for accurate orientation for the pathologist; however, a degree of tissue manipulation during specimen radiography and pathologic processing is inevitable.33 All methods of margin assessment have varying technical or practical limitations, which in turn carry important clinical implications. For example, although shaved margins are associated with greater rates of “positive margins” compared with perpendicular-inked margins, the rates of residual disease upon reexcision are comparable between techniques.34

The NSABP defines a positive margin as the presence of tumor at the inked margin, and a negative margin as the absence of tumor at the inked margin. Negative margins have lower rates of local failure compared to those that have involved margins. In one series, the local control rate was 100% among patients with negative margins versus 78% for those without negative margins.35 In practice, positive or unknown histologic margins should prompt reexcision, since such patients are at higher risk for local recurrence even with XRT. For those with positive margins who undergo reexcision, residual disease will be found in approximately 50% of cases, with rates varying depending on histologic subtype. In one series, residual cancer was detected in 67% of invasive tumors with associated DCIS, 50% of infiltrating lobular carcinomas, and 35% of infiltrating ductal carcinomas without associated DCIS.36

Other factors reported to be associated with a higher likelihood of reexcision include younger age, detection by physical exam only, smaller tumor size, and the presence of EIC. In one series, among 2770 patients undergoing BCS, 60% of patients underwent reexcision. Reexcision was more common among patients less than 40 years of age and with DCIS or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) on final histology. Among those undergoing reexcision, the number of reexcisions performed did not predict for local recurrence.37 Other studies have also demonstrated that negative margins can be achieved in as many as 95% of cases that undergo reexcision.38 As such, for patients with positive margins, reexcision should be performed to achieve negative margins. The number of excisions required does not affect local failure rates; however, multiple excisions may affect cosmetic outcome.

Less clear are cases where the margin is reported as “close.” Over the last decade, efforts have been made to classify margin status based on the distance of the tumor cells from the inked margin (< 1 mm, < 2 mm, etc). Subset analysis of breast-conservation trials looking at local recurrence rates based on varying definitions of negative margin (Table 61-1) have failed to support that excision of additional tissue results in decreased rates of local recurrence. Institutional policies vary both in terms of the definition of a “close” margin and XRT practice patterns based on proximity of cancer cells to the margin edge. Studies reporting higher rates of local recurrence among patients with “close” margins are limited and discordant in their findings.39

While data consistently show that positive margins carry a greater risk of local recurrence,40,41 a negative margin does not guarantee the absence of residual disease.30 However, it is believed that the residual disease burden in patients with negative margins is small enough to be controlled adequately with XRT. Finally, there is renewed interest in the finding of LCIS at the margin. Although studies examining this question have had discordant results, it appears unlikely that LCIS at or close to the margin leads to greater risks of local failure.42-44 As long as final margins are negative for invasive carcinoma or DCIS, patients with LCIS should receive postoperative XRT and adjuvant therapy in the same manner as those without LCIS, and remain appropriate candidates for breast conservation.45

Oncoplastic surgery cannot be described as a specific technique or procedure. Instead, it should be thought of as the joining of old plastic surgery principles with a new concept of oncologic surgery. We have moved away from a surgical philosophy that once aimed to remove as much as possible, to a more modern philosophy that aims to remove “as much as needed, as little as possible,” and that conserves breast tissue as a result. The goal of oncoplastic surgery is to follow standard oncologic principles while ensuring an acceptable cosmetic outcome to patients.46-52 Oncoplastic techniques may allow for a greater extent of resection with simultaneous reconstruction of the residual defect.53 Oncoplastic techniques are used to remodel both the affected tumor-bearing breast and the nonaffected breast with the goal of achieving symmetry.54

Appropriate removal of tissue consistent with oncologic standards

Breast reconstruction to correct breast tissue defects

Immediate reconstruction with plastic surgery techniques

Correction of contralateral breast asymmetry

Oncoplastic techniques may be used when the necessary oncologic procedure results in significant breast deformity.55 Although 90% of patients treated with BCS rate their cosmetic outcome as excellent or good, cosmetically poor outcomes such as extensive scarring, breast deformity, and asymmetry are a reality for some. Unsatisfactory results are often due to poor patient selection, poor surgical planning (ie, unfavorable incision placement, greater breast resection than expected due to intraoperative findings), and/or postradiation changes. Surgical correction of severe cosmetic defects may be complex and require extensive tissue resection, including mastectomy with autologous or heterologous reconstruction. These procedures may difficult for the breast-conservation patient to accept.

Breast cosmetic defects following resection are difficult to classify. This is partly due to the differing contributory factors such as incision type and location, size and shape of the breast, tumor location, size of defect, extent of skin resection, and use of radiation therapy. The morphologic classification described below was proposed in 1987 to characterize breast deformities that follow surgery in the setting of breast conservation, and is currently used to plan surgical correction in oncologically related breast deformity cases.56 This classification identifies 4 deformity subtypes as follows:

- Type I: Distortion and displacement of the nipple-areolar complex (NAC)

- Type II: Insufficient skin, subcutaneous tissue, or both

- Type III: Breast retraction

- Type IV: Severe deformity secondary to radiation therapy

Such deformities most frequently occur when (1) volume loss is 20% or more of total breast volume; (2) the tumor is located in the inferior or medial quadrants, or in the retroareolar region of the breast; (3) axillary dissection is undertaken through the incision used for partial lumpectomy; and/or (4) the surgeon fails to mobilize the breast parenchyma.

Another indication for oncoplastic surgery is when women with significant breast hypertrophy request breast-reduction surgery at the same time as their cancer surgery.

BCS employing oncoplastic principles is contraindicated when mastectomy is necessary to achieve microscopically tumor-free margins. This may be due to large tumor size, extensive malignant calcifications, or the presence of multicentric disease.

Breast remodeling can be obtained by techniques that use autologous tissues other than breast tissue, or by mobilizing breast tissue after resection. In the first case, flaps are used to reconstitute missing tissue volume. The most frequently used flap is the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap. This flap is also conveniently used as a second option to correct a poor cosmetic outcome deriving from BCT (conservative resection plus radiation) and only rarely requires correction of the contralateral breast for symmetry. In patients for whom breast remodeling is done by mobilizing breast tissue within the resected breast, parenchymal flaps are used to “fill in” the defect. The most commonly used oncoplastic techniques that use mobilization of residual mammary tissue are the superior and inferior pedicle vertical mammaplasty techniques. A third technique that should be mentioned is remodeling the breast after removal of the central breast region, including the NAC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree