Stage 0

Latent/subclinical stage

Swelling not yet evident

Impaired lymph transportsubtle changes in imaging

Stage I

Clearly visible swelling with soft pitting

Swelling temporarily reduced by elevation/during night-time

Stage II

Increasing fibrosis and excess fat

Pitting is less pronounced/not detectable

Swelling not reduced by elevation

Stage III

Extremely swollen

Fibrotic and hard tissues

Pressure does not leave any pitting

Skin changes (papillomas, hyperkeratosis, blisters leaking lymphatic fluid)

Fig. 62.1

Lymphedema stage III: hard fibrotic tissues. Extremely swollen arm with hard fibrotic tissues and excess fat [47]

62.6.1 Volume Measurements

So far, there is no standard method for quantitative assessment of lymphedema. Arm circumference or volume difference compared to the unaffected arm or preoperative measurements of the ipsilateral arm can be used to describe the amount of lymphedema. However, diurnal variation and temporal changes due to diet and external temperature as well as weight change can affect the arm volume results. Also, there is natural asymmetry, with the dominant arm usually 1.6% larger than the non-dominant arm [48]. The generally adopted diagnostic criteria for lymphedema are a 10% or 200 ml limb volume difference/change or a 2 cm circumferential difference/change [49, 50]. In very slim patients, smaller arm circumferential differences can be noteworthy. Moreover, in a very obese patient, 2 cm change in the circumference may not be a relevant definition for lymphedema.

Probably the most commonly used method is circumferential tape measurements at defined intervals (e.g. 4 cm) and using specific anatomical landmarks (e.g. styloid process of the ulna at the wrist) as a starting point.

The water displacement method is considered to be the gold standard for measuring arm volume. In this method the arm is immersed in a water tank, and using Achimedes’ law, the volume of the arm is calculated from the amount of water displaced. The benefit of the method is that it has proven to be very reliable, and also the volume of the hand can be measured. Still, it is rarely used due to impracticalities in the clinical setting.

Perometry is an optoelectronic measuring device that uses infrared light beams in a form of a square frame. The arm is placed inside the frame, and the frame is moved along the arm calculating the volume of the arm from the cross-sectional area. Perometry is considered to have high inter- and intra-rater reliability [51, 52]. Perometry is also very hygienic since there is no direct contact with the extremity and the measuring device. However, it is rather expensive and space-consuming equipment.

62.6.2 Measurements of Tissue Water Content

Bioimpedance spectrometry (BIS) is a non-invasive method for measuring water content in tissues. The device passes a small electrical current through the limb and measures the resistance to current. The higher the water content (lymphedema) in the interstitial tissue, the lower the resistance (impedance). Bioimpedance spectrometry can be helpful in detecting early-phase lymphedema, but is not accurate for advanced stages when lymphedema has progressed to a more fibrotic and fatty consistency [53, 54].

The tissue dielectric constant (TDC) can also be used to measure water content. The method utilizes a handheld non-invasive device that passes an electrical current to a local point when the probe touches the skin. The reflected signal determines water content at that specific anatomical point. Being easy to use and low cost, TDC-devices are a practical asset in the clinical setting. Like bioimpedance spectrometry, tissue dielectric constant is most useful in tracking subclinical lymphedema [55, 56].

62.6.3 Imaging Techniques

Although the diagnosis of lymphedema is usually made clinically, imaging techniques can be used to confirm the diagnosis of lymphedema in uncertain cases. In assessment of breast cancer-related upper extremity lymphedema, especially if presenting in a delayed fashion, recurrence of previous breast cancer needs to be ruled out by routine imaging methods.

Advanced imaging techniques are valuable to obtain more detailed understanding of lymphatic function and to monitor the results of lymphedema treatment.

Lymphoscintigraphy is currently the main imaging modality for diagnosing lymphedema [8, 47, 57]. In this technique, a small amount of 99 m technetium-labelled tracer (e.g. nanocolloid) is injected intradermally into the interdigital space. The injected radiotracer is filtered to lymphatics and transported to lymph nodes. Visualization with a gamma camera provides a two-dimensional qualitative evaluation of lymphatic function and pathways. Also semi-quantitative information in the form of a transport index can be obtained based on clearance rates and dermal backflow parameters [58, 59].

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance lymphangiogram (MRL) using gadolinium contrast media provides more detailed three-dimensional image of the lymphatic system. It is non-invasive and involves no ionizing radiation. MRL shows good potential having higher spatial and temporal resolution and therefore being more sensitive in defining the anatomical and functional status of lymphatics [60–62]. With limited availability, relatively high costs and need for special expertise, MRL is not yet a standard diagnostic tool for lymphedema.

The most promising advance in the field of lymphatic imaging is indocyanine green (ICG) lymphography [63, 64]. In this method, a small amount of ICG, a fluorescent molecule, is injected intradermally. When the skin is illuminated by near-infrared light, the light emitted by fluorescent ICG in the lymph vessels is detected by using a special camera, and the lymphatics can be visualized. The ICG lymphography pattern changes from a normal linear pattern to an abnormal dermal backflow pattern depending on the severity of lymphedema. Yamamoto and colleagues proposed a staging method based on different ICG lymphography patterns [65]. ICG lymphography is useful in preoperative planning and provides real-time observation of functioning lymph vessels during surgery. Its disadvantage is that it can only detect vessels if they are less than 2 cm deep [63].

62.7 Conservative Treatment

Conservative treatment should be started as soon as the early signs of lymphedema start to develop. Early treatment can limit progressive arm volume increase and thus prevent irreversible tissue changes [66].

62.7.1 General Measures

On obese or overweight patients with lymphedema, weight loss is essential. These patients should be offered referral to a dietician as a part of lymphedema treatment. Weight reduction has been shown to decrease excess arm volume [67]. Patients with normal weight should be strongly encouraged to avoid weight gain.

Adequate hygiene and skin care are important to prevent cracking of dry skin and help to avoid infections that might exacerbate lymphedema.

Flexibility exercises are beneficial in maintaining the range of movements in the affected arm. Patients should be encouraged to have a physically active lifestyle that also supports weight control. Slowly progressive resistance exercises and lightweight training can be performed safely [68, 69]. By activating the musculoskeletal pump and increasing muscle strength, exercises may alleviate lymphedema symptoms [70, 71].

62.7.2 Compression Garments

Elastic compression garments (sleeve and glove/gauntlet) are the mainstay of lymphedema treatment. The aim is to limit fluid accumulation in the tissues and reduce arm volume. Compression garments should be fitted by properly trained personnel since poorly fitting compression garments are uncomfortable and can even aggravate lymphedema. Some patients may need custom-made garments if ready-made garments are not suitable. Compression garments are usually worn during the daytime, and the patient should always have at least two sets of garments: one to wear and one to wash. Compression garments are renewed every 6 months or whenever they lose elasticity. Compression garments are the first-line therapy in mild (stage 0–1) lymphedema [66, 70, 72].

62.7.3 Decongestive Lymphatic Therapy

Decongestive lymphatic therapy (DLT) or complex/complete decongestive therapy (CDL) is the standard of care for moderate to severe (stage II–III) lymphedema. Some of the patients with mild (stage I) lymphedema might also need more intensive treatment if the symptoms are not controlled by compression garment alone [66, 72, 73]. DLT consists of manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), multilayer compression bandaging, therapeutic exercises, skin care and properly fitted compression garment.

DLT starts with an intensive period aiming to reduce the amount of fluid in the tissues. MLT is performed preferably 5 times a week by a specially trained physiotherapist, and after each session, the arm is wrapped in a multilayer bandage. Therapeutic exercises are repetitive «pumping» movements that, combined with external compression, aim to enhance fluid flow.

After an intensive period of MLD and bandaging when the arm volume is reduced (usually 2–4 weeks), a compression sleeve and glove/gauntlet are fitted. During this maintenance phase, the patient wears compression garments at least during the day. Some patients may also require night-time compression garments or bandaging to control fluid accumulation. The intensive phase of DLT is repeated if necessary at the time of renewing the compression garments.

62.8 Surgical Treatment

Although conservative therapy continues to be first-line treatment for lymphedema, surgical management aiming to improve function and quality of life can be considered in selected patients. Severe or recurrent episodes of cellulitis may indicate surgical treatment is appropriate.

In obese patients, weight reduction should be a prerequisite for operative consideration. Surgical management options can be divided grossly in two categories: mass reduction (debulking) techniques and reconstructive (physiologic) techniques. Mass reduction techniques, such as liposuction, offer a palliative remedy, whereas reconstructive techniques, including lymphatico-venous anastomosis, vascularized lymph node transfer and lymphatic vessel transplantation, aim to restore lymphatic function. Despite of the recent advancements in surgical techniques, none of the operations can definitely cure lymphedema. There are no standardized protocols for surgical management of lymphedema, and objective long-term results are scarce. Neither are there comparative studies of different treatment options.

The choice of operative treatment should be evaluated individually. Different techniques can be also combined depending on the patient’s condition and the surgeon’s preferences.

62.8.1 Liposuction

At present liposuction is the most common mass reduction technique. Long-term lymphedema results in the deposition of adipose tissue and even massive local fat hypertrophy. Especially in the late stage of non-pitting lymphedema, when the arm volume is largely dominated by excess fat, compression therapy has limited impact on volume reduction. In these cases liposuction can provide a clear improvement in the patient’s arm function and quality of life. Strict adherence to compression garment use is mandatory before and after operation. Permanent use of compression garments is necessary to prevent fluid reaccumulation after liposuction. If the patient is not compliant to preoperative compression therapy, liposuction is not indicated [77]. Liposuction is performed through small skin incisions with a vibrating power-assisted or ultrasound-assisted liposuction cannula since traditional liposuction may not be sufficient to break up the fibrotic adipose tissue. A preoperatively measured compression garment is applied in the operation room immediately after liposuction to prevent hematomas. Compression therapy is continued lifelong after liposuction. Liposuction is effective in volume reduction, and with rigorous use of a compression garment, it can provide stable long-term results [78]. Liposuction does not, if properly performed, further reduce the already impaired lymphatic transport [79, 80].

62.8.2 Other Mass Reduction Methods

Brachioplasty, as in postbariatric surgery, can be performed to remove excess non-retracted skin in the upper arm when/if oedema is settled after reconstructive procedures.

More ablative operations, such as the Charles procedure (excising the skin and soft tissue on a fascial level and using the skin as a skin graft to cover the defect), are very rarely used in upper extremity lymphedema due to disfiguring outcomes.

62.8.3 Lymphatico-Venous Anastomosis

Lymphatico-venous anastomosis (LVA) or bypass is a technique of connecting multiple distal subdermal lymphatic vessels to superficial nearby venules (◘ Fig. 62.2). This allows lymph to drain directly to the venous system, and the obstructive part of the lymphatic pathway is bypassed. The LVA technique is minimally invasive since the anastomoses are performed through small skin incisions, and the operation can even be performed under local anaesthesia. ICG and patent blue can be used to localize suitable lymph vessel. Identifying healthy functioning lymphatic vessel as well as a venule without venous backflow is necessary for a functioning anastomosis.

Fig. 62.2

Lymphatico-venous anastomosis

LVA is most suitable for patients with early-stage lymphedema that has not yet progressed into the fibrotic, fat-dominating stage. The technique is highly demanding, requiring a skilled microsurgeon and special supermicrosurgery equipment to handle thin-walled, fragile lymph vessels. Patency of the recreated lymphatic pathway is difficult to evaluate postoperatively.

Studies on the long-term effects of LVA report subjective improvement of lymphedema symptoms in the majority of patients [81, 82]. The effect on volume reduction is variable, but approximately half of the patients have been able omit wearing pressure garments [83]. A decreased incidence of cellulitis has also been reported [82, 84].

LVA appears to be a safe procedure with no severe complications reported. Neither has it been shown to impair lymphatic flow or exacerbate lymphedema.

62.8.4 Lymphatic Vessel Transplantation

Lymphatic vessel transplantation or lymphatico-lymphatic bypass uses a lymph vessel as a graft to connect a distal part of the affected extremity to more proximal lymph vasculature [85]. A lymph vessel graft harvested, for example, from the thigh is tunnelled under the skin to bypass the obstructed axilla and sutured distally in the arm and proximally on the neck to reconnect lymphatic vessels. Like LVA, this technique requires microsurgical expertise and supermicrosurgical instrumentation.

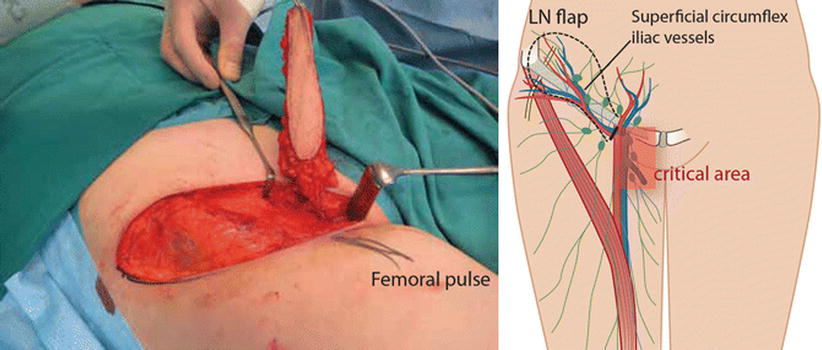

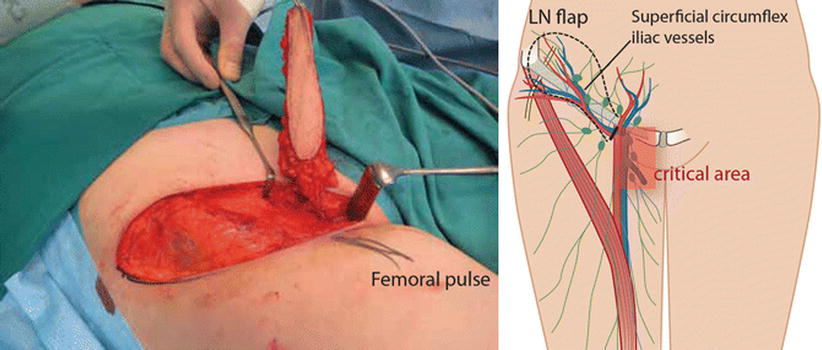

62.8.5 Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer

Vascularized lymph node transfer (VLNT) is a microsurgical method, in which lymph nodes from a healthy lymph basin, most commonly from the groin (◘ Fig. 62.3), are transferred to a lymphedematous extremity, and the artery and vein of this lymph node flap are anastomosed to local vessels to maintain vascularity [86]. Lymph vessels are not anastomosed since they are expected to form spontaneously from the transferred lymph nodes. The exact mechanism by which VLNT improves lymphatic flow is still unclear. It is hypothesized that axillary scar tissue release opens the obstructed lymphatic vessels, and replacing the scar with a well-vascularized flap bridges the distal lymphatics with the healthy proximal system [87]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that lymphatic vessels have an enormous capacity to regenerate after tissue transfer by regrowth of lymphatic vessels and spontaneous reconnections of existing lymphatics [88, 89]. Direct connection with lymph nodes and veins inside the flap allows drainage directly to the venous system [90]. It has also been proposed that the lymph node flap acts as a «pump» that draws fluid from the surrounding interstitium to the transferred lymph node flap by a gradient between arterial inflow and venous outflow [91].

Fig. 62.3

Vascularized lymph node transfer from the groin (schematic drawing and photograph) (Reproduced from Greene et al. Ed, Lymphedema, pp. 269–278, Lymph Node Transfer to Proximal Extremity, Heli Kavola, Sinikka Suominen, Anne Saarikko © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015. With permission from Springer)

Obstruction in the venous outflow being one factor in postoperative lymphedema sequelae is supported by clinical observations that releasing the compressing scar around the axillary vein may sometimes provide immediate relief of symptoms well before the lymphatics have, even theoretically, regenerated.

VLNT can be transferred to either proximal (axilla) or distal (wrist or elbow) recipient sites. The axillary recipient site may be preferable because it allows scar release. Some authors advocate for the distal site based on the pumping effect being more efficient distally [91]. So far, there are no objective studies comparing different recipient sites.

VLNT is considered to be most effective in the early stages of lymphedema when adipose tissue hypertrophy and fibrosis have not yet developed.

In cases of chronic infections or recurrent episodes of erysipelas related to lymphedema, VLNT might be useful since transplanted healthy lymph nodes are expected to improve the local immune response [87]. VLNT to the axilla seems to be beneficial in the treatment of chronic pain, neuromas and brachial plexus neuropathies associated with breast cancer surgery [92, 93]. This is possibly due to wide scar release combined with VLNT, and vascularized soft tissue with active lymph nodes might prevent recurring fibrosis and scarring.

The most common donor site for a lymph node flap is the inguinal area [94], where superficial lymph nodes are harvested based in the superficial circumflex vessels. The contralateral thoracic lymph node flap consisting lymph nodes from the lower axilla along the anterior border of latissimus dorsi muscle [95], the cervical (supraclavicular) lymph node flap based on the transverse cervical artery [96, 97] and submental lymph node flap based on the submental artery arising from the facial artery [98] have also been described for the donor site. The risk of developing postoperative iatrogenic lower limb lymphedema is a major concern for the groin area donor site [99, 100], but with adequate preoperative planning, a delicate surgical technique and with the use of reverse lymphatic mapping [101], the risk can be minimized. None of the donor sites are without risk of postoperative complication. Therefore, all patients must be carefully evaluated and properly advised about possible harms and benefits.

Recent reports of VLNT show promising results, although systematic large-scale studies are still lacking. Most of the studies report a reduction of arm circumference [87, 91, 102]. A decrease in infectious episodes has been observed [87, 91], and approximately 60% of patients have been able to discontinue wearing compression garments [83, 87, 103]. VLNT also seems to significantly improve quality of life among patients with BCRL [102, 103].

62.8.6 Combined Autologous Breast Reconstruction and Lymph Node Transfer

Lymph node transfer can be conveniently combined with microvascular abdominal wall breast reconstruction [104–106]. For postmastectomy patients suffering from upper extremity lymphedema, breast reconstruction with lymph node transfer is an optimal choice. Any soft tissue flap from the lower abdominal wall, either based on the deep inferior epigastric vessels (traditional TRAM-flap, muscle-sparing TRAM-flap or DIEP flap) or superficial inferior epigastric vessels (SIEA flap), can be used as a carrier of lymph node flap. If the abdominal tissue is insufficient for breast reconstruction, transverse myocutaneous gracilis (TMG)-flap with lymph nodes is another option [107].

62.9 Prevention

Any patient undergoing breast cancer surgery is at risk of developing lymphedema at some point in his/her life. Therefore all these patients should be advised about possible adverse effects. Patient education with self-monitoring plays an important role in prevention. Patients should be informed about the early symptoms of lymphedema and encouraged to seek treatment as soon as they recognize these early signs. They should be advised about proper skin care and to avoid infections. Weight reduction in obese patients and maintaining optimal weight is essential since obesity is one of the main risk factors for lymphedema.

Early postoperative physiotherapy and progressive active and action-assisted shoulder exercises combined with education seem to be effective in prevention of lymphedema after ALND [108].

Many other preventative practices (e.g. avoidance of blood pressure measuring or blood sample taken from the ipsilateral arm) have been advocated, although there is no evidence supporting these practices [109].

Early detection of lymphedema should be incorporated in breast cancer follow-up routines. It is recommended to have preoperative measurement of both arms before breast cancer surgery to serve as baseline measurements for further follow-up. Regular monitoring of high-risk patients facilitates early detection and can reduce lymphedema incidence [66, 110]. Measurements based on tissue water content, such as bioimpedance spectrometry or tissue dielectric constant, could possibly predict the onset of lymphedema earlier than volumetric measurements [53, 56].

62.9.1 Preventive Surgery

The use of SNB for axillary staging instead of ALND is the main method of primary prevention, although the risk of lymphedema is not completely absent with SNB. Since ALND is the main risk factor for BCRL, widening indications for SNB (from diagnostic to therapeutic), minimizing the extent of axillary surgery as well as more advanced techniques such as reverse axillary mapping (see ► Chap. 27) might further reduce the risk. Still, these methods need to be carefully evaluated in terms of oncological safety.

Direct lymphatico-venous microsurgery (performing immediate LVAs between the arm lymphatics and collateral branches of the axillary vein at the time of ALND) has been proposed as a promising technique in primary prevention of lymphedema [28], but the need for microsurgical skills may be a limiting factor.

Including lymph nodes in the abdominal flap with simultaneous LVAs in immediate breast reconstruction seems a fascinating way to immediately restore not only breast shape but also lymphatic function for simultaneous prevention of lymphedema [111]. Long-term results of this method are pending.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree